A love letter to Kabul

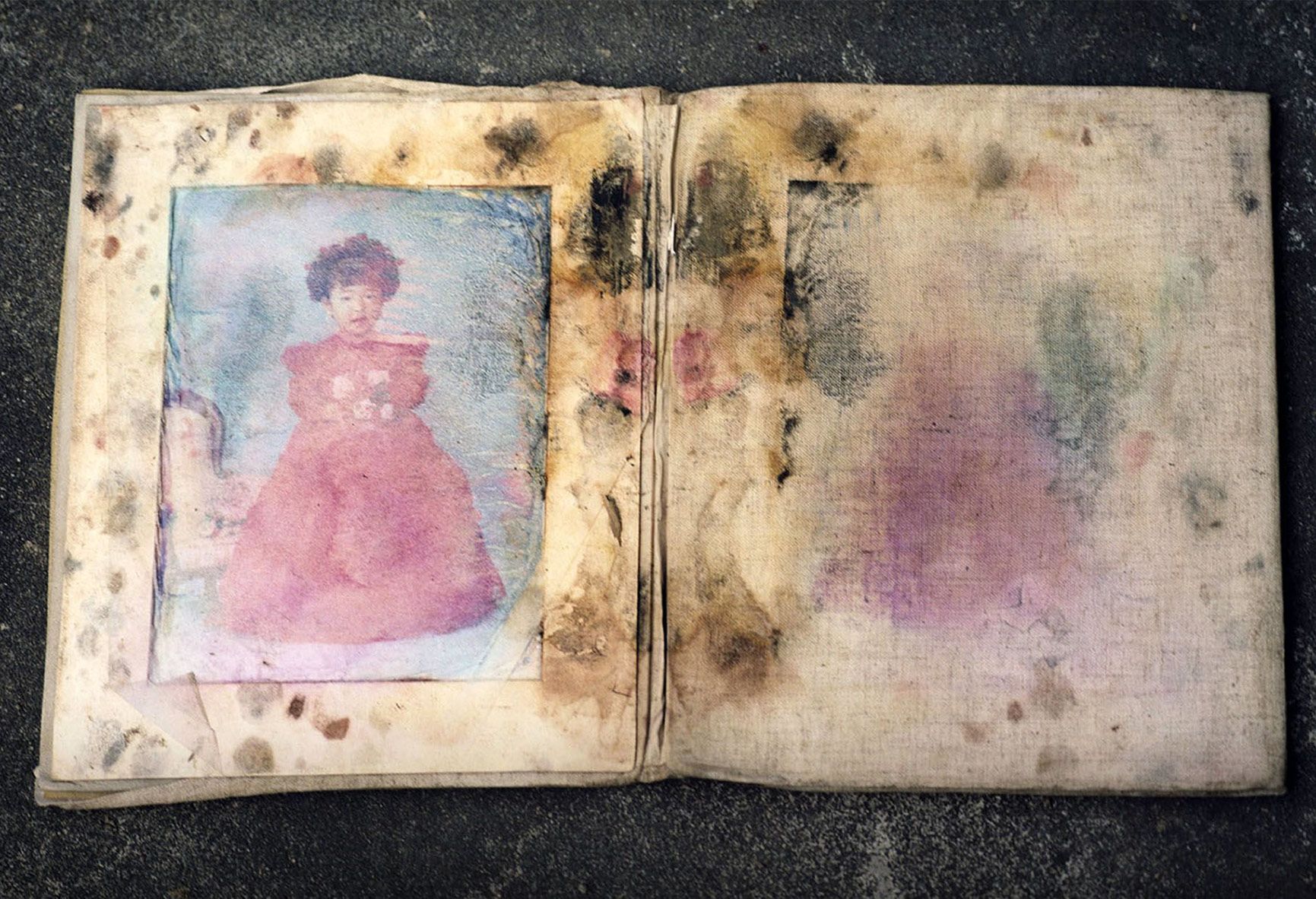

This summer’s Taliban takeover was a seismic moment for Kabul. Those who call this city their own wonder if life has changed forever. Much of what made Kabul special is now a cultural battlefield - evocative street murals have been painted over with Islamic verses, girls’ secondary schools have been shut, stirring music no longer courses through shops and alleys.

Most streets feel safer now that the war that brought the Taliban back is over. But security fears are still ever-present - some fear for their lives under Taliban rule, some fear bombings by the Islamic State. Poverty deepens, painfully so.

But Afghans also know that Kabul’s long and vibrant history gives it breath beyond the headlines. A city buffeted for centuries by epochal events tells its own story. It's written in the stones of ancient bastions and the cement of modern blast walls, and drawn in exquisite palaces, in boxy Soviet-style blocks, and in the gargantuan villas nicknamed “poppy palaces”, for the profits amassed in the lucrative heroin trade, and through hefty US military contracts.

Afghans often call this city, as they would a beloved friend, Kabul jaan - Kabul dear.

In the many years I’ve worked there - my last visit ended in October - I have kept asking myself: what is it about this city which draws people in?

The revered 17th Century poet Saib Tabrizi marvels how:

“No-one can count the beauteous moons on her rooftops,

“And hundreds of splendid suns hide behind her walls.”

Another chapter in Kabul’s tortuous tale has unfolded. Taliban from across the country now claim its streets. Afghans forced to flee - or still desperate to leave - hold fast to their memories. And what memories they are.

Zarghuna Girls’ High School

A prestigious school; a source of pride. It takes its name from Zarghuna Anna, a powerful 18th Century Afghan woman.

Its Kabul schoolyard brims with giggles and chatter. But thousands of girls, in classes seven to 12, aren’t here; the Taliban say most secondary schools for girls must stay shut for now. Afghans fear they will never re-open, just like they didn’t under Taliban rule in the 1990s. Education is now a front line in the battle to protect the rights of Afghan women and girls.

“Zarghuna is a place for girls’ dreams to come true,” reflects deputy principal Rabia Rashid. “I hope the Taliban keep their promise to allow all girls to study.”

Girls and parents poured through its gates after the Taliban were toppled in 2001. Polling booths have been set up here in many elections since then.

I’ll never forget the day when security warnings almost stopped us from dropping by during the 2014 elections. We arrived to see a crush of women voters surging through corridors to cast their ballots - defying Taliban threats.

Streets of Spandi

Kabul’s magnetism resides in the rhythms of this city. But busy streets are teeming with ever more children, including girls of all ages, as well as old men, white-bearded and bent by the merciless war - all begging, living hand-to-mouth.

The city’s stubborn traffic snarls are infuriating. But they’re fertile ground for a growing league of street kids, weaving around vehicles, waving rusted tin cans. Wisps of incense smoke - Spandi - wafting through windows, promise the power of good spirits, for a tiny price. It buys bread to feed a family, and elicits an impish grin. Who could - and should - resist?

Sarai Shahzada money exchange market

Kabul’s money exchange, tucked inside the ancient labyrinth of the old city, buzzes like a stock market. This hub of one-stop financial services has become even more indispensable in the current cash crisis and the strict cap on weekly withdrawals from banks. The Taliban have now announced a ban on the use of foreign currency. It’s been the lifeblood of this economy.

The market is also rich in history. Established half a century ago by Afghan Jewish families, by the late 1980s, when I lived in Kabul, it was dominated by Afghan Sikhs and Hindus. But the last Afghan Jew left his beloved city in early September. Sikhs and Hindus have been leaving, year on year, pushed by persecution during many a chapter of war. Now there are none in this market, hardly any in the country.

Kah Faroshi bird market

Brilliant yellow and blue lovebirds chirp and cuddle in the crumbling old city of Kabul - no matter who rules the roost. Lilting birdsong has infused this meandering lane of mud-walled shops, festooned with cages of wire or wood, for the past four centuries - a wonderful antidote to the worries of war.

It's been the soundtrack of 80-year-old Mohammad Khitab’s entire life. He’s been raising feathered friends since he was a child, through two kings, two coups, two invasions by superpowers, and now Taliban 2.0. “I’ve seen 13 changes of government and raised 20 million pigeons,” he proudly tells me.

He knows the rules now, just like the first time the Taliban were in charge. Buying and selling birds – fine. But no racing pigeons, no cock or pigeon fighting, no gambling. “I don’t know whether they’re un-Islamic or not,” he remarks wistfully. “But I do know these are Afghan hobbies, part of our culture for the past 400 years.”

The last 40 years of war never shut his shop. But business has all but stopped in the city's deepening cash crisis since mid-August.

Pigeons can carry price tags as high as $3,000 to $4,000 (£2,200 to £2,930), a value measured by the colour of their eyes and wings, the size and shape of their beak.

“Why are they so expensive?” I ask the master bird man. “Because they are so beautiful,” Mohammad Khitab exclaims.

Musicians’ lane

Shops are shuttered in the ancient quarter of Kuche Kharabat, beloved instruments hidden from view in the birthplace of the great Ustads, the legends of traditional Afghan music.

“We’ve spent all our life, all our energy, on music,” laments a venerable virtuoso in a darkened room, cluttered with bulky cases, including mega-speakers for celebrations such as marriages. “It’s the only life we know.”

He gently lifts a stringed rubab from a jumble of dusty boxes to strum a soulful rendition of “Watan” – My Homeland, a register of national pride. Now it feels like an act of resistance.

The Taliban haven’t officially banned music yet, as they did the last time they were in power. But at some weddings with live music, their fighters have forcefully stopped it. At others, the music plays on, but only with DJs. Afghans ask, what’s a wedding without music, “the food of love?”

Cafe culture

Afghans traditionally drink tea – lots of it. But coffee has conquered Kabul in the past two decades. Now the Taliban are back, talking to baristas.

“They say we now know about cappuccinos, lattes, espresso, and all our cakes,” recounts Azizullah Gulzada, owner of the popular Cupcake Café. But business isn’t as brisk. Some loyal customers, including young women, are staying away, uncertain of what lies ahead.

Cafes didn’t just change tastes, they changed lives. They provided public spaces for the most educated, connected generation in Afghan history to percolate new ideas and projects, to discreetly socialise in a very conservative society.

“The Taliban may find a thousand reasons to shut us down,” another café owner warns with a shrug.

Babur Gardens

The largest, loveliest public space in a crowded city was first laid out in the 16th Century in the classical “charbagh” four-garden pattern, by the Mughal emperor Babur.

“I heard he was so fond of flowers, green places, and places for relaxation and entertainment,” says 23-year-old Ahmad Shah, a young Talib from Kandahar in southern Afghanistan, when I ask what he knows about Babur. Clusters of young Kandaharis in electric blue turbans and tunics meander through beds of Afghan roses on their first ever visit.

These graceful gardens were ravaged during the chaotic civil war of the '90s, then painstakingly restored after the fall of the Taliban in 2001 by the Agha Khan Trust for Culture. It’s been a cherished destination for visiting dignitaries, for parties and picnics, even the traditional national dance, fired by flutes and drums, the Atan-e-Milli.

“People should have fun, but Islam prohibits music and dancing,” explains Ahmad Shah. “We won’t beat people for doing it. We’ll just tell them they shouldn’t.”

Nadir Khan Hill

The domed marble mausoleum of Nadir Shah and his son Zahir Shah, the last Afghan king, crowns this dun-coloured hill. Its gems have long been bright kites dancing with the wind, an Afghan symbol of freedom. That’s earned this arid mound, with its spectacular view of the city, a whimsical epithet - Kite Hill.

There are only a few tissue paper squares soaring in the sky when we visit.

“The Taliban haven’t banned kites,” insists one young Talib. “Even we’re flying them.” They were taboo in the first Taliban time – kite-flying and kite-fighting.

“Fewer people are visiting now,” regrets the royal tombs’ caretaker Habibullah. “But Taliban are asking me about this history.”

It’s a top spot for Taliban tourism. As the sun sinks, bathing the city in warm golden hues, gaggles of young men from across the country keep showing up, sporting Taliban trademarks – long hair, short-leg trousers, an assortment of shimmering caps and swirling turbans. Sunset is peak selfie time, then time for prayers.

Bibi Mahru Hill

“I really miss our flag,” says Shah Faisal, a former finance ministry official. He’s visiting this popular grassy hilltop dotted with picnic tables and white picket fences framed by multi-coloured roses.

Behind us, a 200-ft high flagpole stretches like an empty needle into the Kabul sky.

Many Afghans say they miss their national standard, a gift from India which once floated above the city. At 97ft x 65ft, there was no bigger tricolour in the country. The Taliban pulled down the green, black and red mega-flag. They’ve speedily produced huge quantities of their white banner with its black Arabic shahada - Islamic declaration of faith - but not yet a supersized one.

The hill, once stalked by thieves, is safer now – although a Talib official ordered us out just after sunset so we didn’t manage to take many photos. It’s mainly Taliban who lounge on its lawns, take in the panoramic view, or clamber up the multi-tiered diving board on the Soviet-built Olympic size swimming pool. It was never used for swimming because water wouldn’t flow up this steep slope; the Taliban dropped people to their death here in the 1990s. It still lies empty, in a city all too full of history.

LYSE DOUCET

LYSE DOUCET

Credits

Writers: Lyse Doucet, with Mahfouz Zubaide and Esmatullah Kohsar

Photography: Paula Bronstein

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Producer: James Percy

Additional photos: Alamy

Published: November 2021

More Long Reads

The lost tablet and the secret documents

The memory hunters