The story of Tunnel 29

In 1961, Joachim Rudolph escaped from one of the world’s most brutal dictatorships. A few months later, he began tunnelling his way back in. Why?

The Tunnel

It all began with a knock at the door. Joachim, a 22-year-old engineering student, was in his room at university in West Berlin. He had been studying there for a few months, spending his free time taking photographs, or going to jazz nights.

At his door were two Italian students he knew in passing who had come to ask for his help. They needed to get some friends out of East Berlin and they wanted to do this by digging a tunnel.

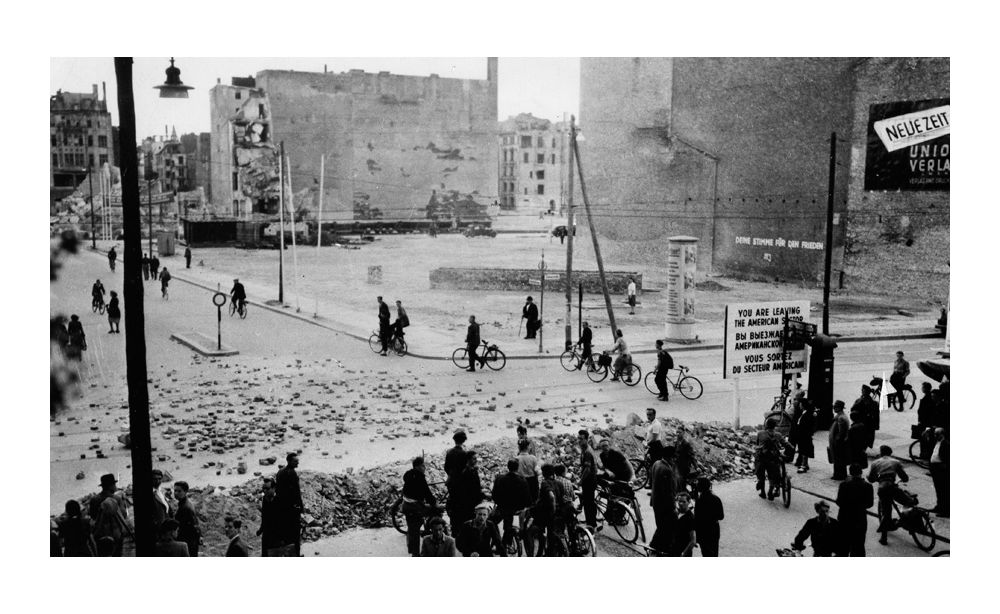

This was October 1961, just two months after the Berlin Wall had gone up. It was built by the East German government to stop the flood of people leaving the communist dictatorship for a better life in the West. But what was so extraordinary about it was the speed with which it had been built.

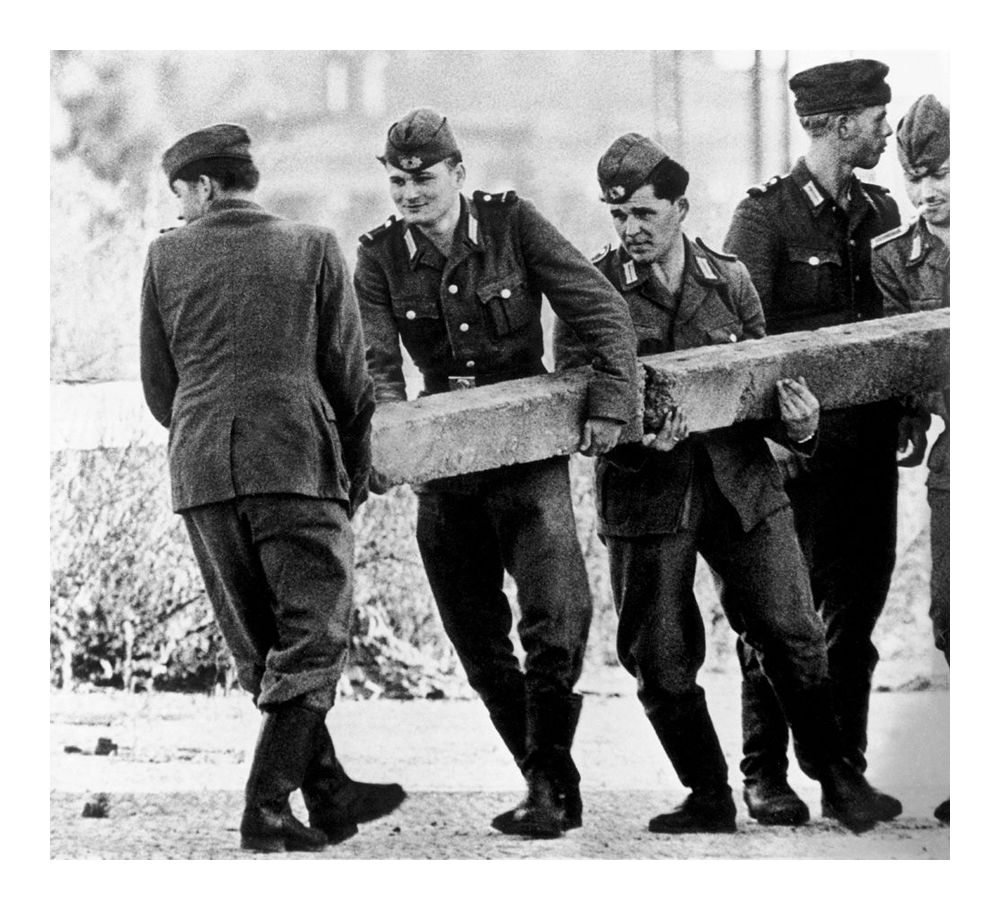

East German soldiers build the Berlin Wall and close access to West Berlin, 1961

East German soldiers build the Berlin Wall and close access to West Berlin, 1961

Tens of thousands of East German soldiers had gone into the streets of East Berlin in the dead of night, stringing barbed wire from posts and making concrete barricades. By the next morning, this barrier cut through the whole city, snaking through parks, playgrounds, cemeteries and squares.

Although the wall had been hastily put together (and wasn’t as tall or as heavily guarded as it would later become) it changed the city overnight.

When people woke up on 13 August 1961, they suddenly found themselves on one side of it. Wives were cut off from their husbands, brothers from their sisters. There were even stories of newborn babies in the West now separated from their mothers.

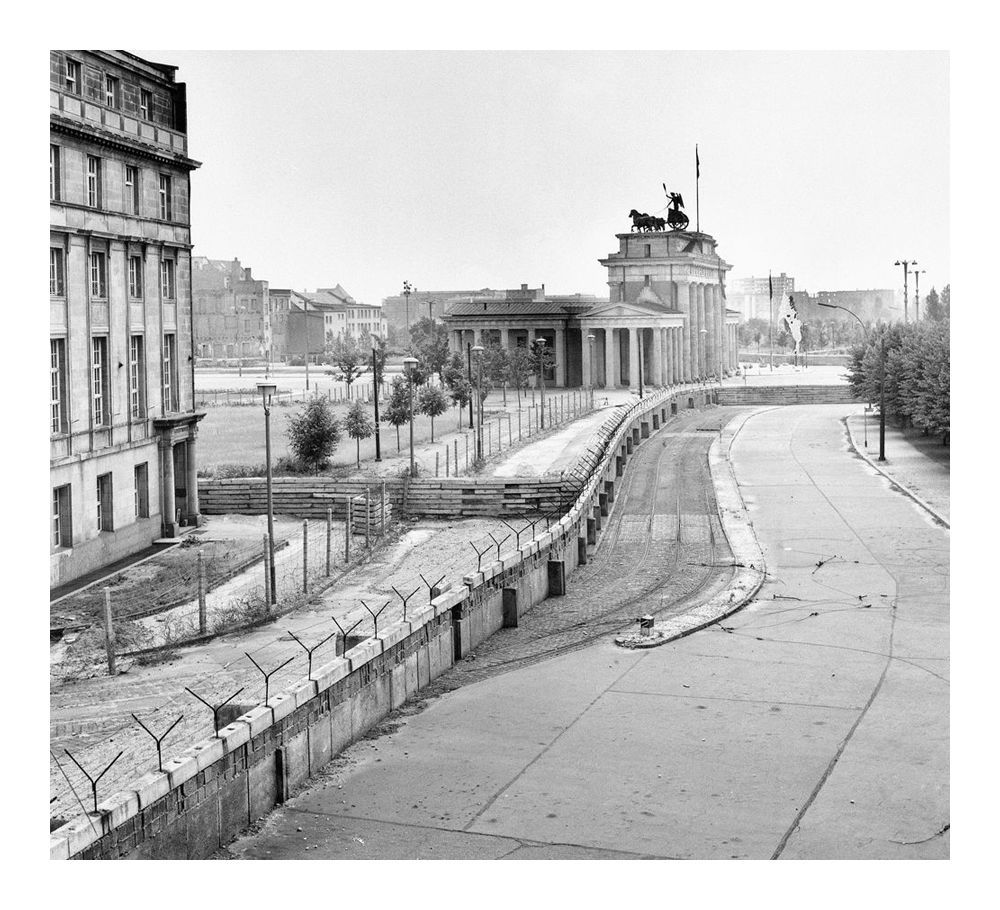

The Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate one year into construction

The Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate one year into construction

Life before the wall had been tough enough - people were fed up with the poor living conditions and the Soviet tanks that showed up every time protesters went out onto the streets. But now, with the wall, the government was displaying its desire for even greater control.

And so the very day the barrier was erected, the escapes began. Some people just jumped over the barbed wire, others were more inventive, like the couple who swam across the River Spree pushing their three-year-old daughter in front of them in a bathtub.

Even East German soldiers and border guards were among those trying to get out.

19-year-old border guard Conrad Schumann jumps over barbed wire to West Berlin in 1961

19-year-old border guard Conrad Schumann jumps over barbed wire to West Berlin in 1961

Then there were the people who sneaked into houses next to the wall, and threw themselves out of the windows, hoping that firemen on the other side would catch them.

Joachim himself had crawled through a field in the middle of the night, making it into the West just as the sun rose. “I didn’t want to be part of this new world,” he says now. “A world where you couldn’t say or think what you want.”

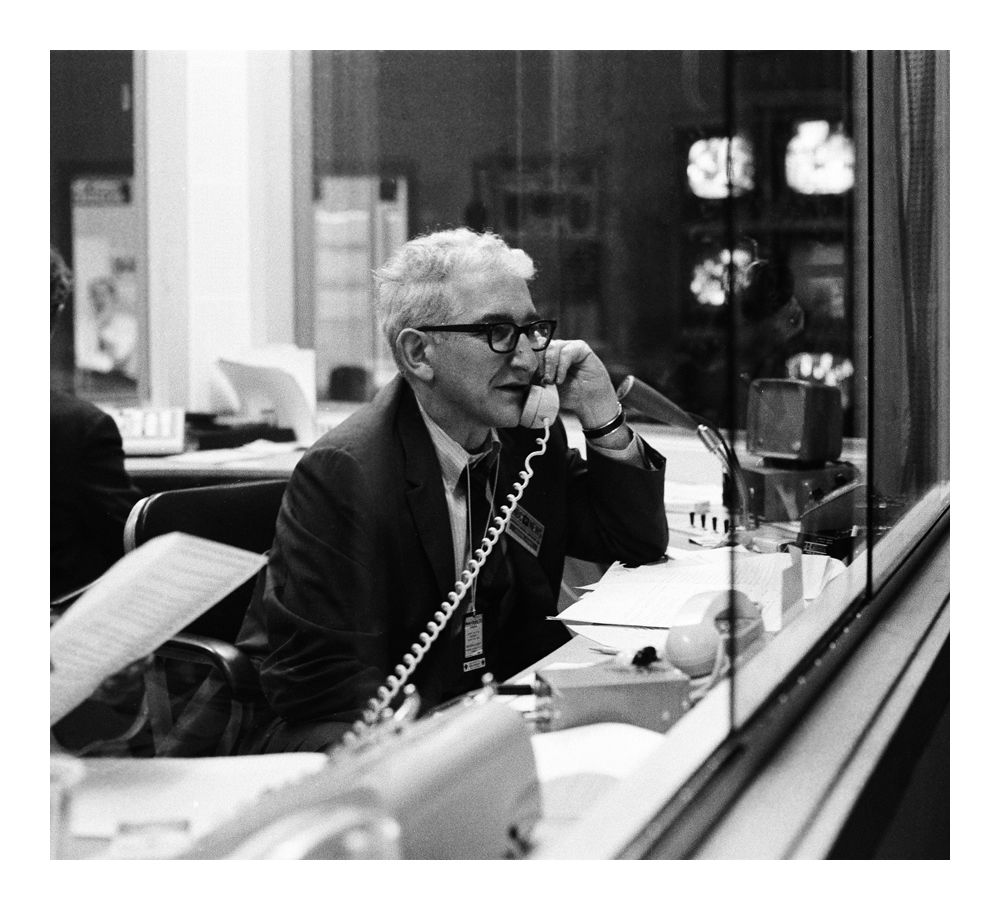

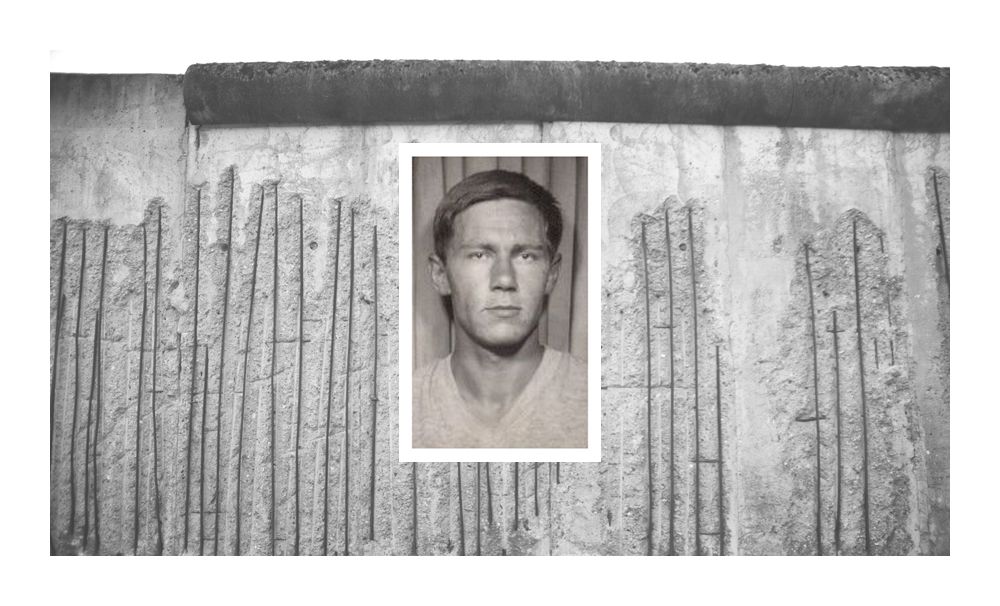

Joachim

Joachim

Now he was in West Berlin, making a new life for himself. But here were these two students, asking him to tunnel back into the country he’d only just escaped from. He could be thrown in prison, even killed.

Despite this, he found himself agreeing to help them.

Digging begins

When you’re a group of students, who have never dug a tunnel before, where do you begin? Like every good heist, they started with maps.

They borrowed them from friends in the government, and pored over them, trying to plot a route for the tunnel. They needed to find a street to burrow under, where they wouldn’t dig into the city’s water table. They chose Bernauer Strasse, which was a bold move.

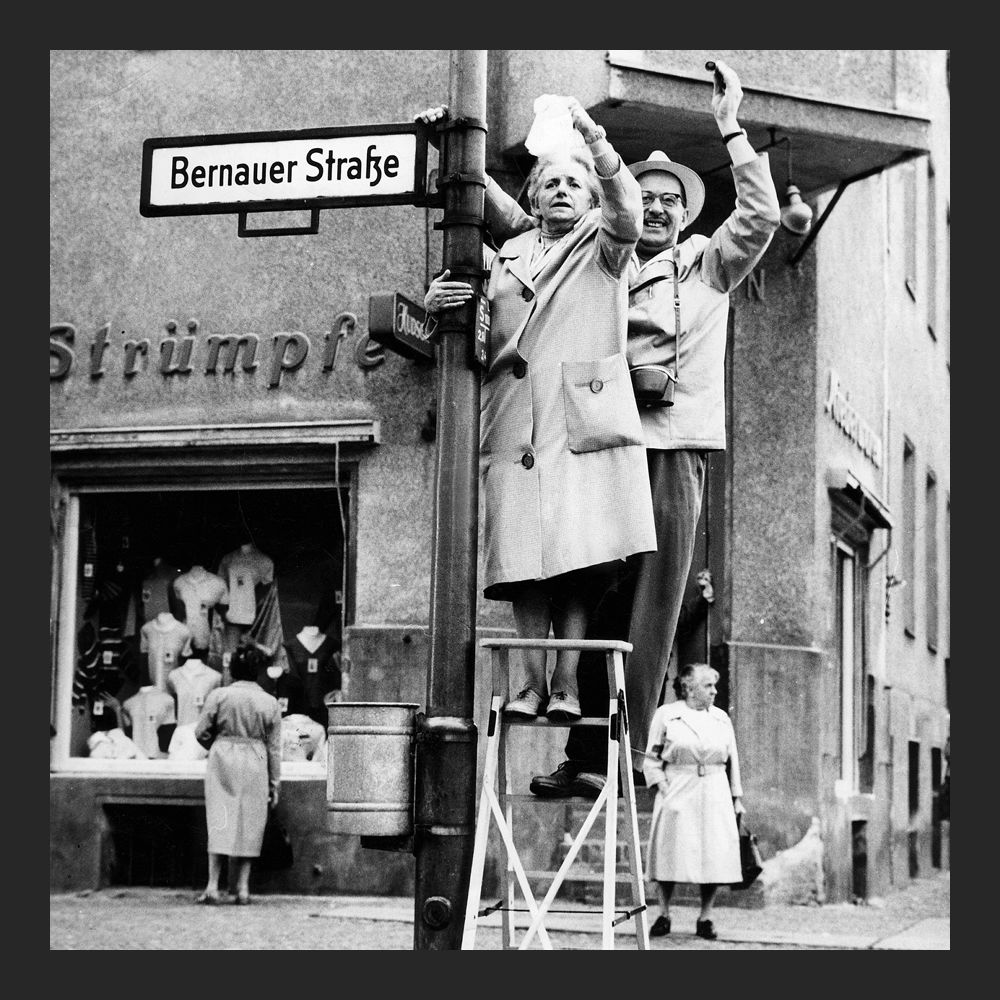

Back in the 60s, this street was world-famous because the Berlin Wall ran right down the middle of it. Tourists would go there to take photos of the wall, so it was always busy. Choosing to dig under Bernauer Strasse was like digging a tunnel under Times Square in New York.

West Berlin citizens waving to East Berlin on Bernauer Strasse, 1961

West Berlin citizens waving to East Berlin on Bernauer Strasse, 1961

Now they had to choose somewhere to start digging. One morning they came across a cocktail-straw factory, set back from the road. They introduced themselves to the owner, concocting an elaborate story about being jazz musicians in need of a rehearsal space. But he guessed what they were up to. He had also escaped from the East and was more than willing to let them use his cellar.

Next, they needed to find a basement in the East to dig to. They chose a friend’s flat, but rather than tell him, they persuaded someone to steal his key and make copies, so the escapees would be able to enter.

Then they started the search for more tunnellers.

This was no easy task. West Berlin was full of spies working for the dreaded Stasi, the East German ministry of state security. It was the most powerful part of the East German government, combining secret police and the intelligence services. Its mission was to know everything - what you thought, who you were married to, who you were sleeping with.

The office and working quarters of the former Minister of State Security (head of the Stasi)

The office and working quarters of the former Minister of State Security (head of the Stasi)

There were even jokes about it: “Why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? Because you get in the car, and they already know your name and where you live.”

They had hundreds of thousands of informants, some of whom had infiltrated government, businesses, hospitals, schools and universities in the West.

Eventually, the tunnellers found three other students they thought they could trust, all of whom had recently escaped from the East: Wolf Schroedter (tall and charming), Hasso Herschel (a Castro-loving revolutionary), and Uli Pfeifer (distraught after his girlfriend had been caught escaping by the Stasi).

Best of all, they were engineering students, so they might have a few ideas about how to dig a tunnel.

Finally, they needed tools. One night they jumped over a wall into a cemetery and stole wheelbarrows, hammers, spades and rakes. Everything was set. On 9 May 1962, just before midnight, digging began at the factory.

“We had no idea where to start,” says Joachim. “We’d never seen a real tunnel. But we’d seen footage of tunnels on TV, ones that had failed, and that gave us ideas about how to dig one.”

View of the Berlin Wall at Bernauer Strasse.

View of the Berlin Wall at Bernauer Strasse.

Over the next few nights, they dug straight down, 1.3m exactly. Now they could start digging horizontally towards the East. This was the moment they realised how difficult it was going to be.

“When you were down in the tunnel, you had to lie flat on your back,” says Joachim. “You’d point your feet in the direction you were digging, you held onto the spade with both hands, and you’d use your feet to push it down into the clay.”

It would take them hours to dig out a small heap of earth. They’d put it on a cart, and with an old World War Two telephone that Joachim had found, ring through to the cellar to alert them that the cart was ready. Someone would then pull the cart up on a piece of rope.

Before long, they established a steady rhythm, spending hours at the factory, digging and hauling carts of clay. After a few weeks, though, they were exhausted. Their hands were covered in blisters, their backs ached, but they had little to show for it. They hadn’t even reached the border. They needed two things - people and money.

The Death Strip

By the end of June 1962, the students had dug around 50m - almost all the way to the border. They’d been digging for 38 days, eight hours a day.

With the NBC money, they had bought new tools - enabling them to recruit more people to dig - and bought steel to make a rail line for the cart.

The tunnel was soon looking pretty hi-tech, with Joachim its chief inventor. He strung up electric lights, attached a motor to the rails so the cart full of earth would whizz along faster, and he taped hundreds of stove pipes together to bring in fresh air from the outside. Filming all of these contraptions were two Bavarian brothers.

There is no sound in the NBC footage because the tunnel was too small for a tape recorder. On one occasion when they were able to bring down a microphone, you can hear a tram, a bus, and footsteps. “It was incredible,” says Joachim. “You could hear everything.”

But as they dug further into the East, the sounds above the tunnellers disappeared. Now they were right under the “death strip”, a section of land next to the wall, patrolled by armed border guards who were on the look-out for tunnels.

Theirs wasn’t the first tunnel to be dug under the wall. There had been others, but most had failed. Only a few weeks earlier, border guards had caught two men digging - shots were fired and one was killed, the other badly injured.

“The border guards had special listening devices that they’d put on the ground,” says Joachim. “If they heard something, they’d dig a hole and fire a gun into it or throw in dynamite. So as we dug, we knew that at any time, the ground above our heads could suddenly be ripped open.”

Sometimes they could even hear the guards talking. “And we knew that if we could hear them, there was a chance they could hear us. So we couldn’t talk anymore when we were in the tunnel.”

Fans had to be switched off, which meant it was hard to breathe at the front of the tunnel. All they could hear was the wind and the sound of their own breathing.

“Then there were the sounds that you could never work out,” says Joachim. “Was it the Stasi? Were they coming for us?”

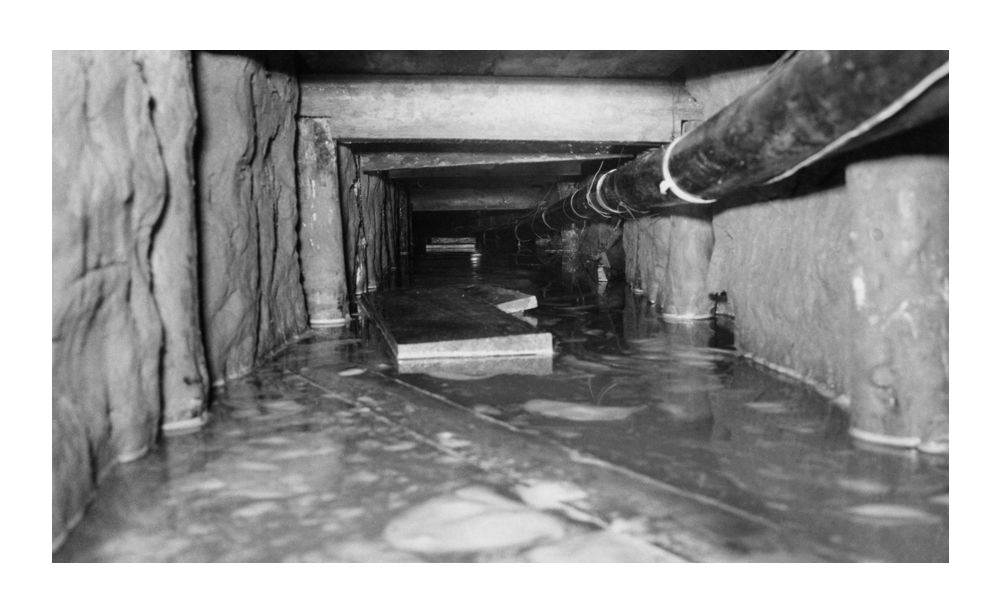

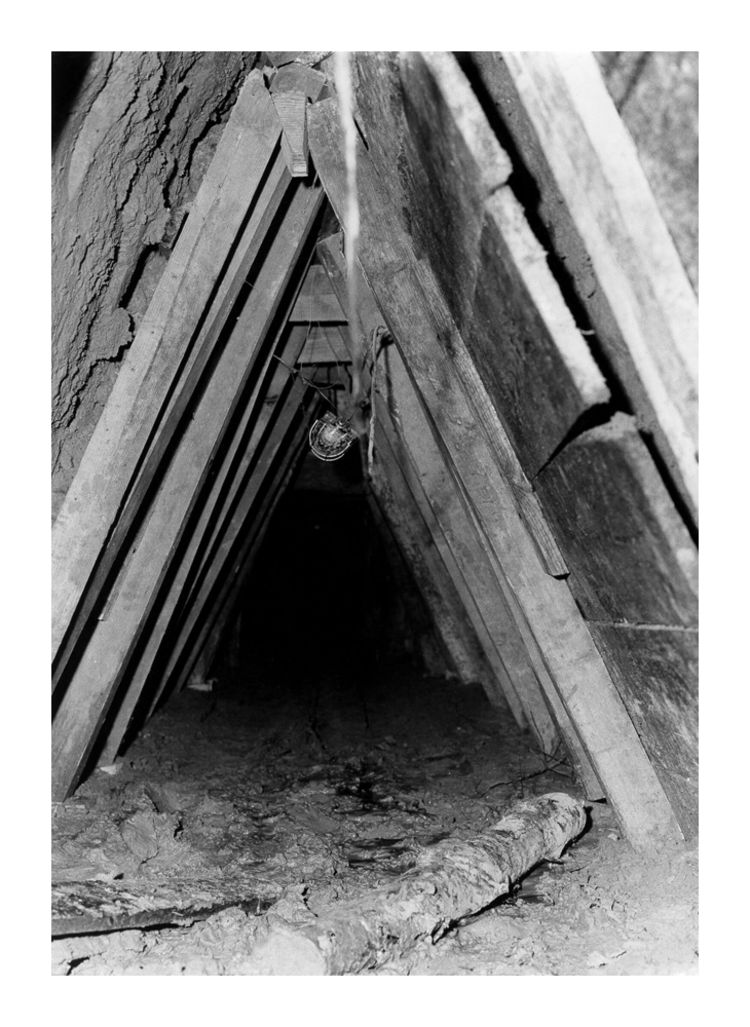

The original Tunnel 29 during the leak

The original Tunnel 29 during the leak

One evening, Joachim was digging when he heard a dripping noise. The tunnel had a leak. Within a few hours, water was flowing in. The tunnellers realised a pipe must have burst, and they knew that if the water kept coming, they’d lose the tunnel.

They came up with a risky plan - to ask the West Berlin water authorities to fix the pipe. To their surprise, they agreed. But after it was fixed, the tunnel was still waterlogged. It would take months to dry out.

They had been so close - just 50m away from the basement in the East. All the people they wanted to get through to, were ready and waiting - Hasso’s sister, Uli’s girlfriend.

The Second Tunnel

It was now July 1962, almost a year since the wall went up. Tripwires had been added, as well as landmines, electric fences, spikes, spotlights, and should these fail to stop an escapee, the border guards were armed with pistols, machine guns, mortars, anti-tank rifles and flame-throwers.

But every month, the escapees kept coming. Some hid in cars, others used fake passports.

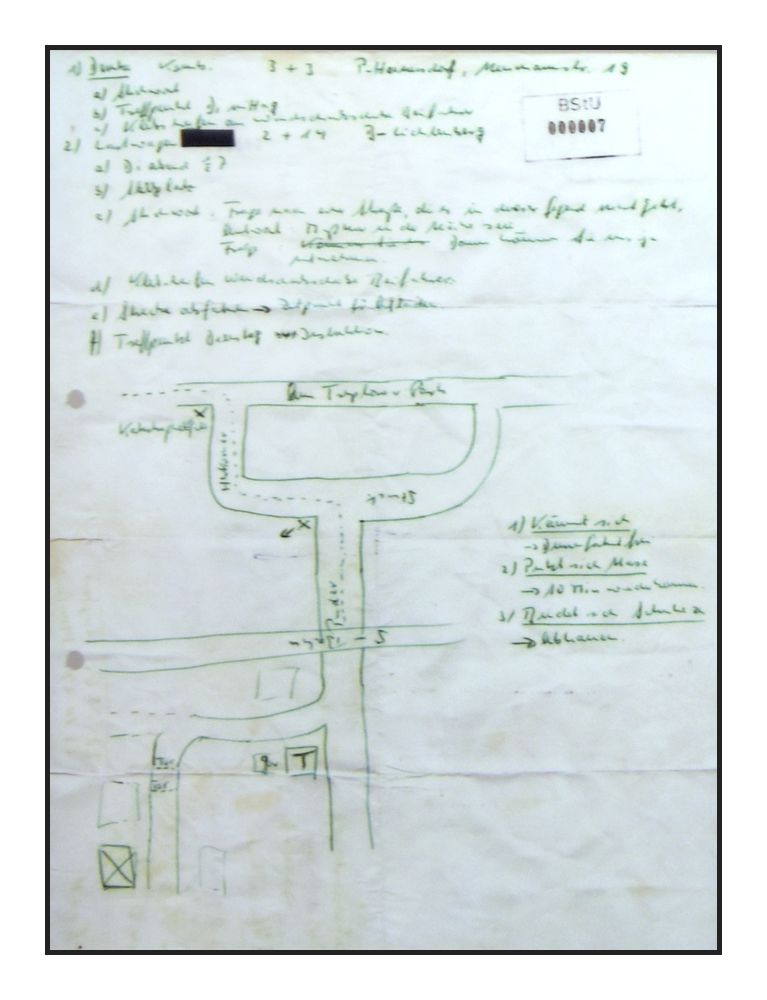

The tunnellers could no longer sit and wait for the tunnel to slowly dry out. Eventually, they heard about another tunnel that had been dug into the East, but left abandoned and unfinished.

The students who had planned this other tunnel asked Joachim and the others if they would be interested in joining forces. They could combine their lists of escapees and get them all through at the same time.

“It seemed too perfect an opportunity to pass up,” says Joachim. “We were a group of diggers without a tunnel, and here was a tunnel that needed diggers.” They were given just a few details.

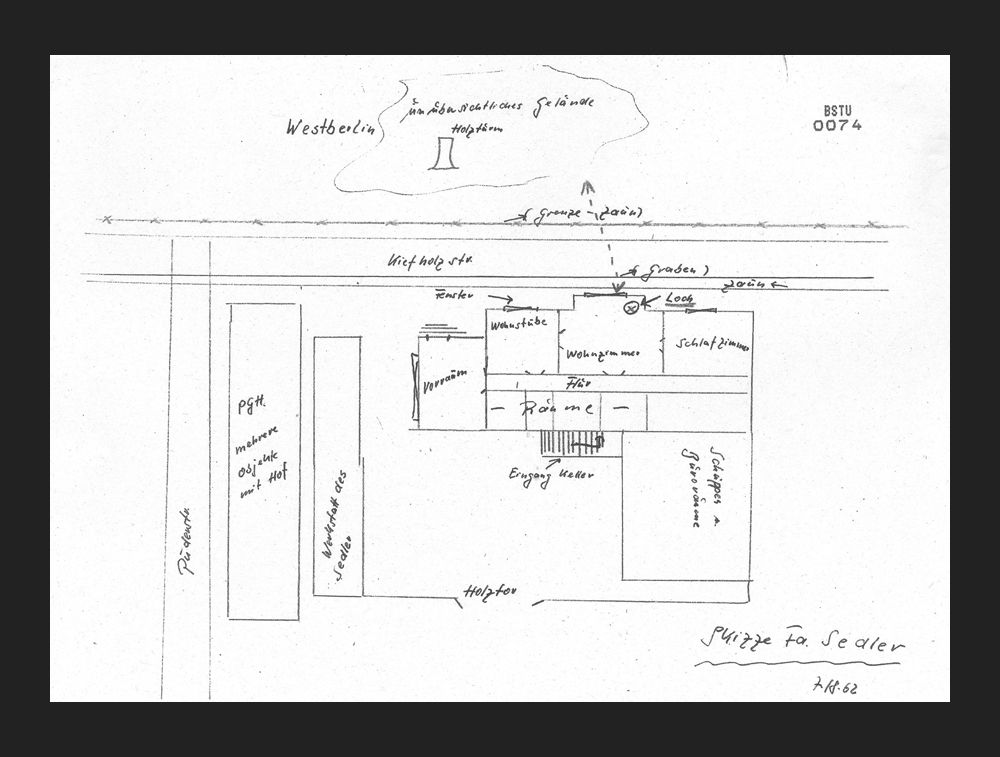

Sketch of the house and surrounding area of the nfiltrated tunnel.

Sketch of the house and surrounding area of the nfiltrated tunnel.

The tunnel was meant to emerge underneath a cottage in East Berlin, and about 80 escapees were hoping to crawl through it. A few days later, they went to see the tunnel. “It was a complete shock,” says Joachim. “It was nothing like ours.”

Joachim’s tunnel had lights, telephones, motorised pulley systems, air pipes. This one had no lights, no air pumped in, and the ceiling was so low you could hardly crawl. Every time a car went over the road above, clay would trickle down into the tunnel.

But they decided to stick with it, enlarging it and digging the final few metres until they were directly under the cottage. The tunnel was ready. Now all they needed was a messenger to pass on details to the escapees.

Wolfdieter Sternheimer was another student living in West Berlin. He had heard about the tunnel and had volunteered to help, in return for getting his girlfriend out of the East. Her name was Renate and they had fallen in love after becoming pen-pals and writing letters about “the Beatles and the great questions of life,” he says.

Sternheimer was useful because unlike all the other tunnellers, he was born in West Germany, which meant he could go into the East whenever he liked.

Over the next few weeks, he went in and out of East Berlin, updating the escapees. The date of 7 August was fixed.

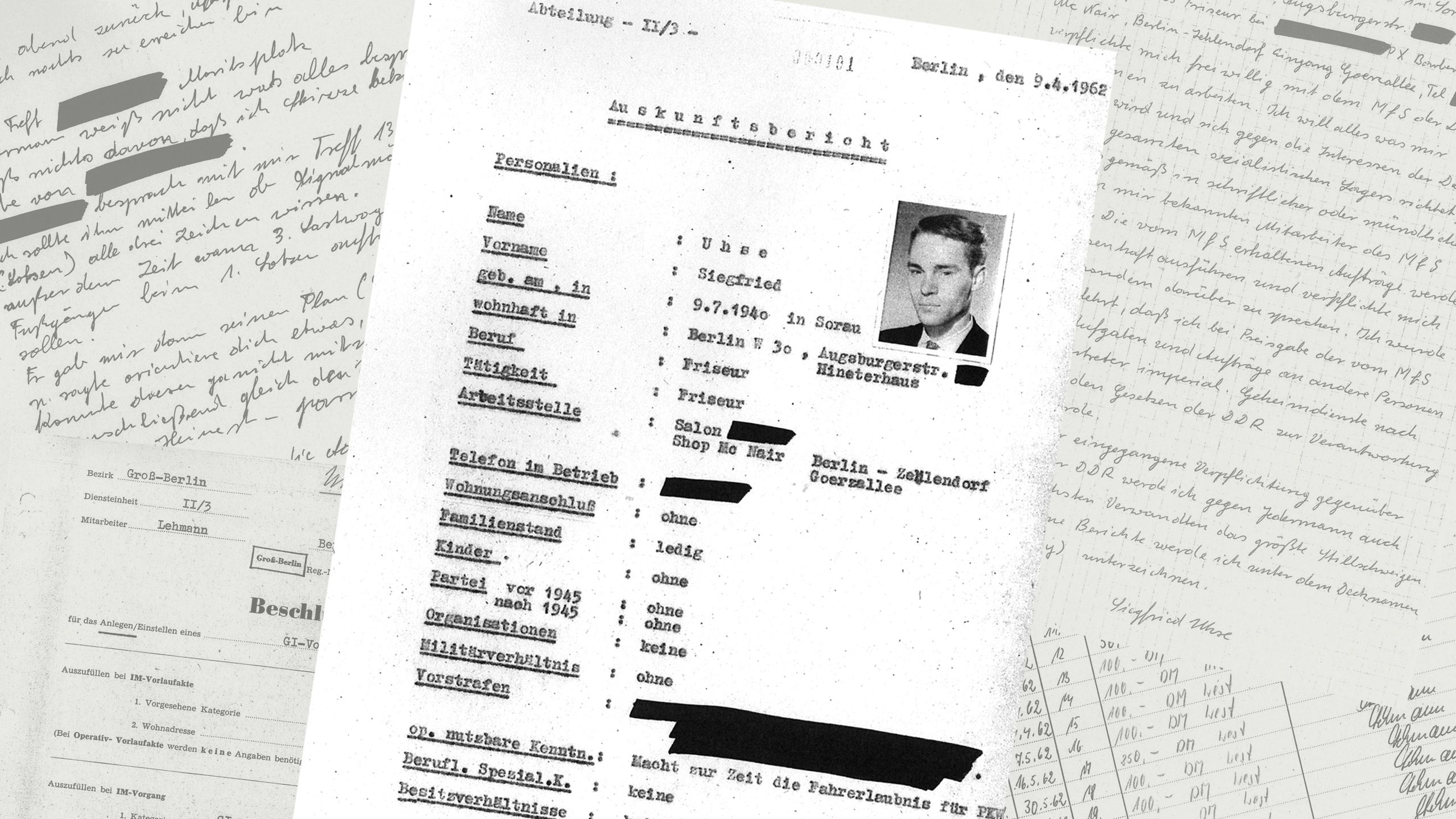

The day before, a meeting of the student organisers was called. Among them was a man Sternheimer says he had never seen before. His name was Siegfried Uhse, and he was a hairdresser.

It was Uhse who stepped forward eagerly when a volunteer to go to the East to deliver final instructions was sought.

But directly after the meeting, instead of going home, he went to a flat codenamed “Orient” where he met his Stasi handler.

Uhse was an informant, who had been recruited six months earlier. The report from that day records what he told his superior: “The breakthrough would happen between 4pm and 7pm” and “100 people were expected.”

The Stasi were now onto Joachim’s tunnel - the biggest escape operation so far from West Berlin.

The Trap

Escape day arrived. All over East Berlin, men, women - including Wolfdieter’s fiance, Renate - and children, started to make their way towards the cottage. They set off at different times. Some walked, others took the bus or tram.

Most of them were terrified. They’d hardly slept the night before, spending hours packing and re-packing the one bag they could take with them, squeezing in nappies, photos and clothes. Once they reached the West, this would be all they had to start their new lives with.

As they made their way to the cottage, the Stasi machine kicked in. The commander of the border brigade ordered soldiers, an armoured personnel carrier and a water cannon to meet at a base near the cottage. Then, finally, plain-clothes Stasi agents were sent to the cottage. When they got there, they spread out into the streets and waited. The trap was set.

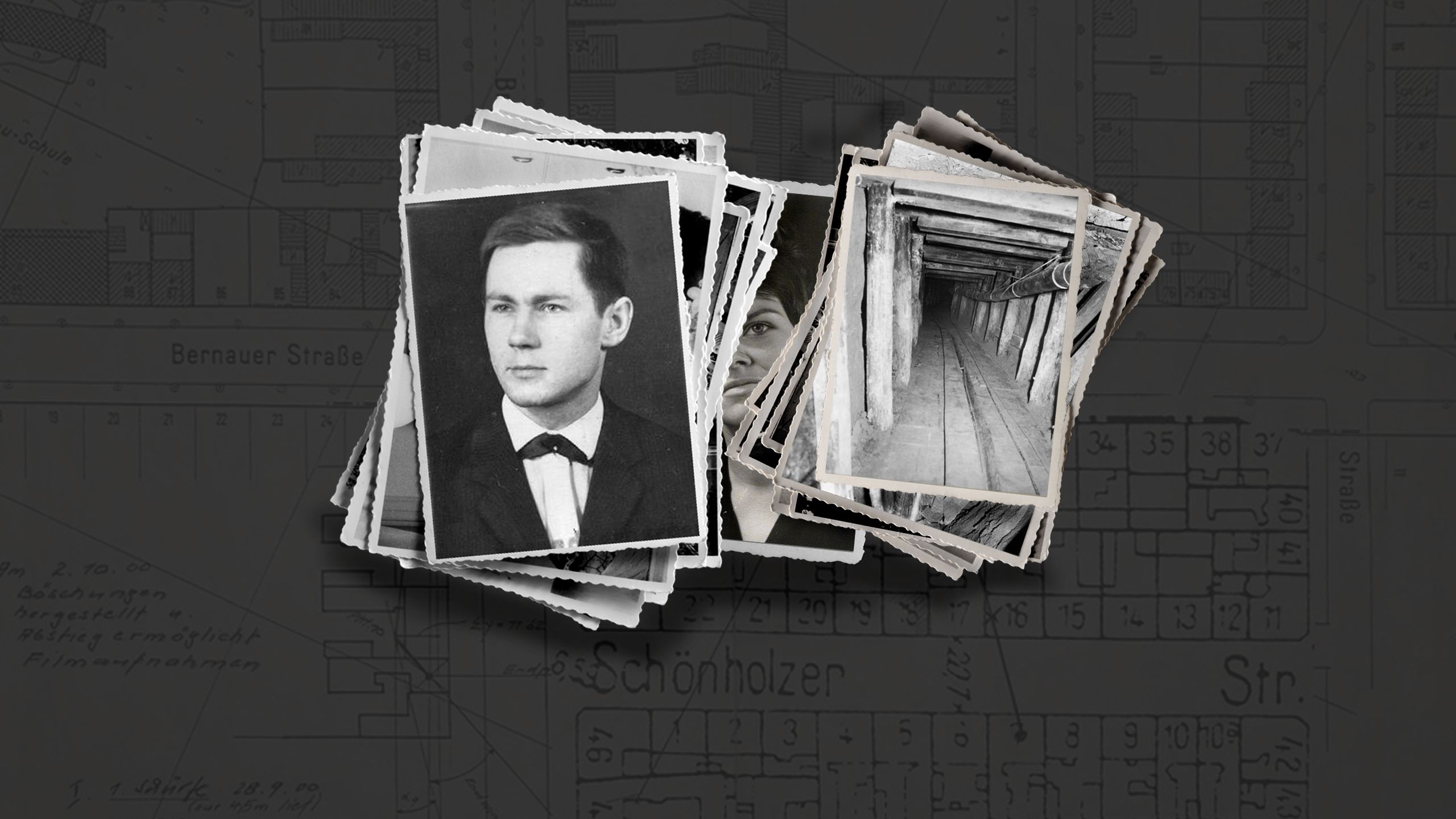

Map, acquired by Stasi spy Siegfried Uhse, showing plans for the first tunnel - BSTU

Map, acquired by Stasi spy Siegfried Uhse, showing plans for the first tunnel - BSTU

Back at the tunnel, Joachim, Hasso and Uli were preparing for the breakthrough. These engineering students were afraid. They had never done anything like this before and had no idea if they would even be able to hack into the cottage, or what they would find when they did.

They collected everything they needed - axes, hammers, drills and radios. They had also managed to get hold of pistols and even an old WW2 machine gun.

“We wanted to be able to defend ourselves in case the Stasi were on to us,” says Joachim.

Slowly, quietly, they started crawling down the tunnel. When they reached the end, they started hacking into the floor above them.

It was now four in the afternoon and above them, on a street outside the cottage, people were arriving. But when there was no chance of escape, Stasi agents suddenly turned on them, bundling them into cars and driving them away.

Underneath them, Joachim, Hasso and Uli were still hacking into the cottage, unaware the operation had been blown.

“Then suddenly we heard something over the radio from the West,” says Joachim. “They were shouting at us to come back.”

But the tunnellers kept going. “All we could think about were the people coming to the cottage and we didn’t want to let them down,” says Joachim.

They carried on hacking into the floor, until finally they broke into the living room. They held a small mirror up so they could see into the room. It was empty except for a few chairs and a sofa. It was eerily quiet - too quiet. But they had come this far and had to go on. They climbed up into the room and Joachim crept towards the window. He peered through the side of a curtain.

“I saw this man in civilian clothes, just outside the house, creeping under the window. I knew straight away he was Stasi.”

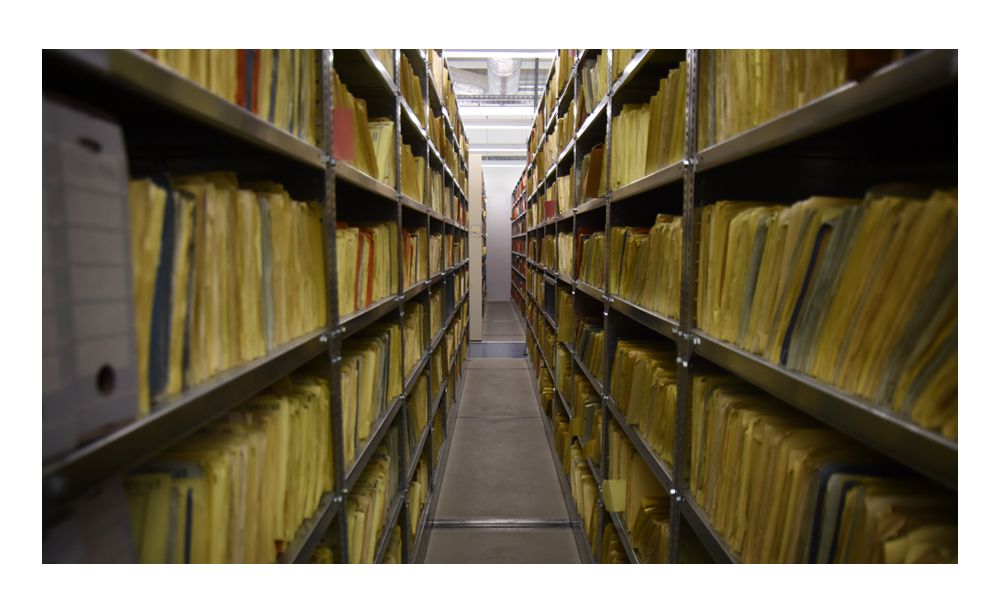

The Stasi Archives

The Stasi Archives

They were terrified. They knew the operation had been blown, but what they didn’t know was that a group of soldiers was now standing right outside the living room door, Kalashnikovs in their hands.

There’s an astonishing moment that’s recorded in a Stasi file (one of more than 2,000 files I read while researching this story, all held in the former Stasi headquarters). The report states that soldiers were about to burst in to the living room when suddenly they heard one of the tunnellers mention a machine gun. They paused and decided to wait for back-up. They knew their Kalashnikovs were no match for a machine gun.

That pause saved the lives of the tunnellers. They jumped back through the hole into the tunnel and started crawling as fast as they could back into the West, their bags of tools and weapons swinging against their legs.

They knew that at any moment, the soldiers could burst into the room, follow them into the tunnel and shoot after them. It was only a few minutes later when the soldiers rushed into the living room and entered the tunnel, but it was empty.

The Stasi agents were too late to catch the tunnellers. But they had something else - dozens of prisoners to interrogate.

The Interrogation

By now, only one person was unaware the operation had been blown - Wolfdieter. He’d been in the East helping out with the operation, and now he was on his way back to the border, excited about seeing Renate. When he arrived at the checkpoint, two men were waiting for him. He knew straight away he had been caught.

First, he was questioned by the police. Then they turned him over to the Stasi. They took him to Hohenschönhausen prison, an old Soviet prison now repurposed by the Stasi. “It was the middle of the night,” remembers Wolfdieter. “I was strip-searched, then given prison clothes. And then the interrogation began.”

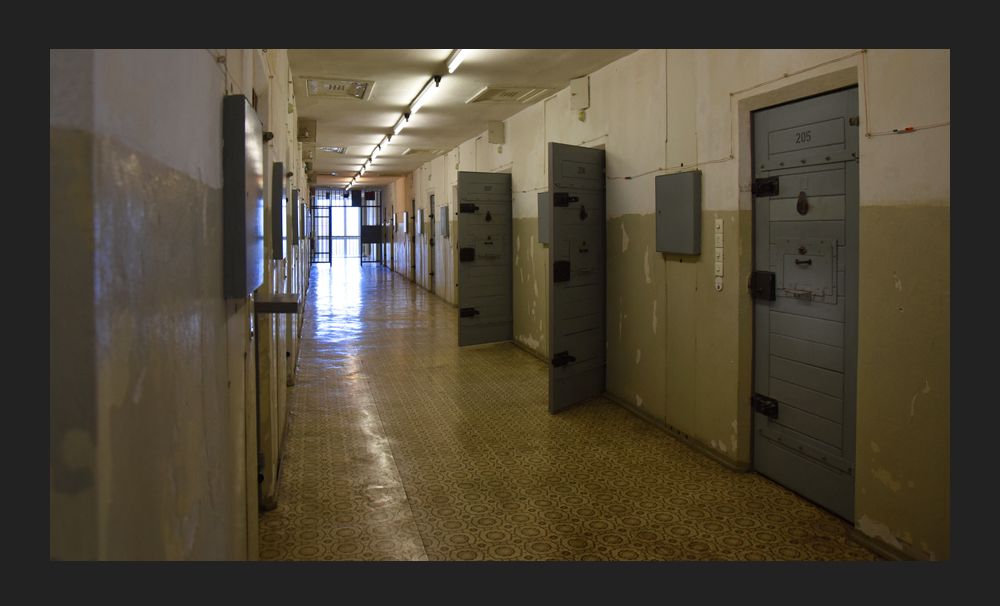

Cells at the Hohenschonhausen Prison, the main prison of the former East German Communist Ministry of State Security, the Stasi

Cells at the Hohenschonhausen Prison, the main prison of the former East German Communist Ministry of State Security, the Stasi

In the 1950s, the Stasi had been infamous for carrying out physical torture. By the 1960s they were relying more upon techniques for psychological torture.

Stasi manuals focusing on how to extract information using these new techniques were published, and senior Stasi officers would teach recruits how to interrogate prisoners at special universities.

The psychological pressure began with the prison itself, which was designed to slowly crush the spirit of its inmates. Prisoners weren’t allowed to talk to each other. There was no chatting, no solidarity.

In their cells, they had no control over anything - the light switch was on the outside, as was the button to flush the toilet. Then, at some point, the prisoners would be taken to the interrogation room.

An interrogation room at the former Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen Memorial, Berlin.

An interrogation room at the former Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen Memorial, Berlin.

“The first interrogation went on for 12 hours,” remembers Wolfdieter. “They don’t have to beat you. You are tired, there’s no water, no food. Nothing.”

The transcript of Wolfdieter’s interrogation is 50 pages long. His interrogator asks him a series of questions and then goes back over each one, again and again. A few hours later, a new interrogation starts - the same questions, over and over. Bit by bit, tired, hungry and thirsty, he tells them everything.

Wolfdieter was sentenced to seven years’ hard labour. And he wasn’t the only one. Many of those arrested at the tunnel that night were now in prison, even mothers, separated from their children.

The Second Attempt

You would think that after the operation had been blown, with so many arrested and imprisoned, that the tunnellers would give up. They didn’t. They knew the Stasi had no details about their original tunnel and so they decided to try again.

This time, they would keep the details tighter and the group of diggers smaller. It was now September 1962, and the original tunnel had dried out enough to allow work to re-start. But before long, it sprang another leak.

This time, they were too far into the East for the West German water authorities to fix it. The diggers would either have to abandon the tunnel or break through into a random basement.

Using their maps, the tunnellers worked out they were now under Schönholzer Strasse, a street in the East that was so close to the wall it was patrolled by border guards.

Tunnelling up there would be a huge risk - it would be noisy, and what's more, any escapees would have to walk past the border guards to enter the cellar.

It was hard to imagine how it could work, but these diggers had proved they were brave and they were determined to give it another go.

Tunnel 29, after the leak had dried out.

Tunnel 29, after the leak had dried out.

The date was set for 14 September. Some students volunteered to go into the East and tell the escapees the new plan. But like last time, they would need a messenger to cross the border on the escape day itself and give signals, so that the East Berliners would know when to go to the tunnel.

Unsurprisingly, after what happened to Wolfdieter, no-one was keen to step forward. But then one of the tunnellers, Mimmo, had an idea - what about his 21-year-old girlfriend, Ellen Schau? Like Wolfdieter, she had a West German passport so she could go in and out of the East, and as a woman, perhaps she would arouse less suspicion? Ellen agreed to do it.

The escapees had been told to go to three different pubs and wait. Once the tunnellers had broken through into the cellar, Ellen was to go to each of these pubs and give a secret signal.

Ellen was filmed as she boarded a train into the East. Wearing a dress, headscarf and sunglasses, she looks like a 60s movie star. You see her check her watch. It’s midday. She turns towards the station and runs up the stairs.

A road block at the border to East-Berlin

A road block at the border to East-Berlin

Meanwhile, Joachim and Hasso began hacking into the cellar of an apartment on Schönholzer Strasse. Joachim eventually climbed up into the cellar and unlocked the door to the apartment lobby using a set of skeleton keys.

He needed the number of the apartment they'd dug into. First, he went into the hall. No number there. And he realised the only way to find out was to go outside into the street - the street that was patrolled by border guards.

He opened the front door to the building and saw a group of guards sitting in a hut. They were distracted, so he slipped out into the street. “There was a big number seven just above the door,” he says.

They used their trusty WW2 telephone to get a message to the rest of the team, who were in a West Berlin flat overlooking the wall. A white sheet was draped from the window - Ellen’s signal that the escape was on. From the East, Ellen saw the sheet and went to the first pub to start giving the signals.

“It was really loud,” Ellen remembers. “And when I walked in, the men all turned round and looked at me. The signal was for me to buy a box of matches. So I walked up to the bar, and that’s when I noticed these people staring at me.”

It was a family, sitting at a table. The mother was wearing a dress and high heels, holding her toddler on her lap. Ellen ordered the matches and left. In the next pub she ordered some water - that was the next signal.

When she arrived at the final pub, things didn't go quite to plan. The signal there was for her to order a coffee, but the waiter said they had run out. “It was a terrible moment,” she says. “How could I give the signal if the pub didn’t have any coffee?”

Instead, she started complaining loudly about the coffee, and ordered a cognac. She drank it, turned around, saw two families waiting and hoped they understood the signal. She left the pub. Her job was done.

As she made her way back to West Berlin, small groups of people started walking towards Shonholzer Strasse. They were doing their best not to stand out, just a few at a time.

Joachim and Hasso were waiting in the cellar, guns in their hands. Just after 18:00, they heard footsteps. “We stood there, hardly breathing, gripping our guns tightly,” says Joachim.

The door opened. The mother from the first pub, Eveline Schmidt, stood there, with her husband and two-year-old daughter. They were helped down into the tunnel. “It was dark,” says Eveline. “There was just one lamp by the entrance. One of the tunnellers took my baby and then I started crawling.”

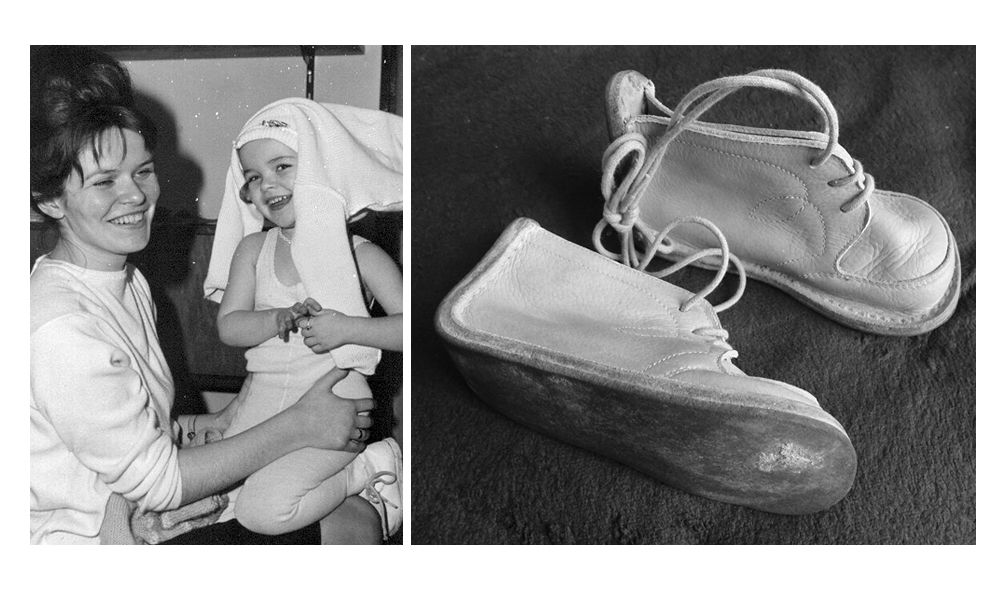

Eveline Rudolph with her daughter Annett, whose shoes Joachim finds in the tunnel

Eveline Rudolph with her daughter Annett, whose shoes Joachim finds in the tunnel

At the other end, in the West, the two-man NBC film crew were standing at the top of the tunnel shaft. In the footage of this moment, for a long time nothing happens, and then suddenly a white handbag appears. Then there’s a hand, and then, finally, Eveline.

She’s covered in mud, her tights are torn and her feet are bare. She’s lost her shoes somewhere in the tunnel. It’s taken her 12 minutes to crawl through it. She looks up towards the camera, blinking into the light. And then she starts climbing the ladder up into the cellar. Just as she reaches the top, she collapses.

One of the NBC cameramen catches her and helps her to a bench. She sits there, shaking, and then one of the tunnellers brings her baby to her. She bundles her into her arms, nuzzling the nape of her neck.

Over the next hour, more people came. There was Hasso’s sister, Anita, and others - eight-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 80-year-olds. By 23:00, almost everyone on their list had made it through.

The tunnel was filling with water, but one digger was still waiting. His name was Claus, and he was hoping his wife, Inge, might come.

Inge had been sent to a communist prison camp after she was caught trying to escape with him. She’d been pregnant at the time and he hadn’t seen her since.

In the NBC footage, the camera is focused on the tunnel. Suddenly, a woman emerges. Claus pulls her towards him, but she carries on going - she doesn’t recognise her husband in the dark. He looks up after her, then hears another noise coming from the tunnel.

It’s a baby, dressed in white, carried by one of the tunnellers. He’s tiny - only five months old. Claus bends down and gently takes the child, delivering it from the tunnel. It’s a boy, his son, born in a communist prison.

Back at the other end, in the East, Joachim was still in the cellar. Twenty-nine people have made it through. With the water up to his knees, he knew it was time to go. “So many things went through my head,” he says.

“All the things we’d gone through digging it. The leaks, the electric shocks, all the mud, so much mud, the blisters on our hands. Seeing all those refugees come through, I felt the most incredible happiness.”

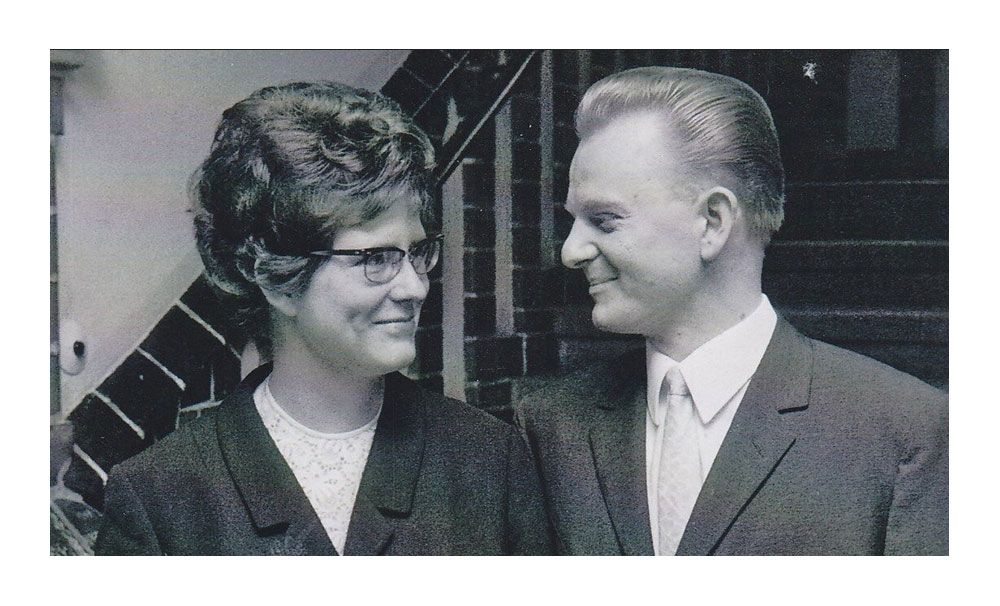

Wolfdieter and Renate on their wedding day in 1966

Wolfdieter and Renate on their wedding day in 1966

A few months later, NBC broadcast the film, despite an attempt by President Kennedy’s White House to block it, fearing a diplomatic incident with the Soviet Union.

It was described as without parallel in the history of television. The tunnellers heard that President Kennedy himself watched it and that he had been moved to tears.

And what about the tunnellers? Wolfdieter, the messenger caught by the Stasi, was released from prison after two years. Siegfried Uhse was given one of the Stasi’s top medals for infiltrating the tunnel. Wolf Schroedter and Hasso Herschel worked on other tunnels, and Mimmo’s girlfriend Ellen, the brave courier, wrote a book about her experience.

And, finally, what about Joachim? There’s one final story to tell. A few years after the escape, he fell in love with Eveline, the first woman who came through the tunnel. Her marriage had broken up and 10 years after he rescued her, he married her.

Joachim and Eveline Rudolph standing outside 7 Schönholzer Strasse, the flat the tunnel came up under

Joachim and Eveline Rudolph standing outside 7 Schönholzer Strasse, the flat the tunnel came up under

On the wall of their apartment today, there’s a pair of shoes that he picked up a few days after the escape. Little did he know when he found them in the tunnel that these belonged to Annett, Eveline’s daughter. And so the tunnel that Joachim built, which brought 29 hopeful refugees from the East, also brought him a family.

Finally, what about the wall?

At least 140 people were killed at the wall before it was pulled down in November 1989. Right now, more walls are being built, dividing cities and countries, but Joachim says there’s one thing they have in common.

“Wherever there’s a wall, people will try to get over it.” Or, perhaps, he should say, under it.

Helena Merriman tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel right under the feet of Berlin Wall border guards to help friends, family and strangers escape in a BBC Radio 4 podcast.