There were nine...

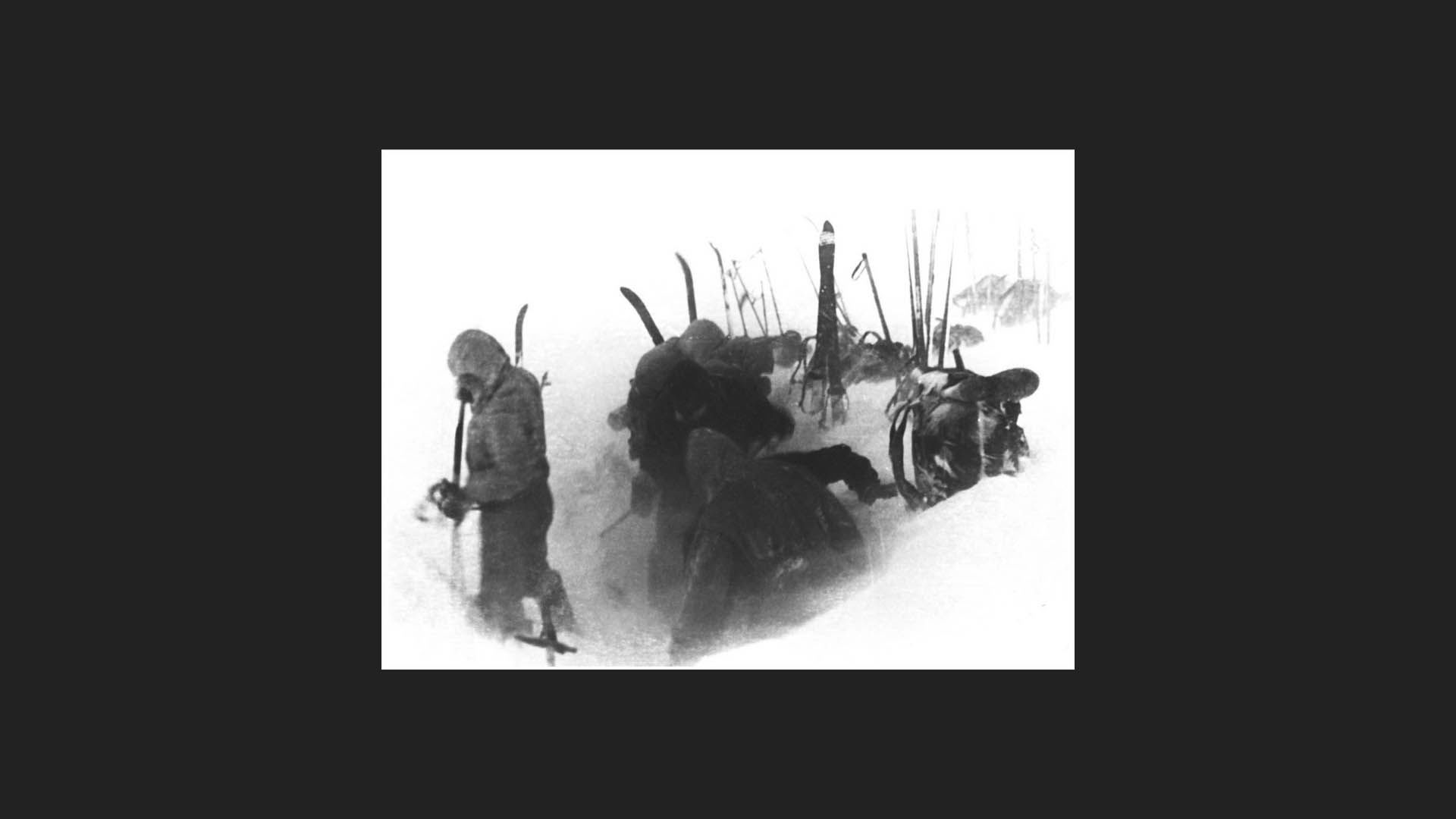

In the dead of winter, a group of students set out on a trek into the Ural Mountains. Their frozen bodies - with inexplicable injuries - were discovered in locations that compounded the puzzle of how they died.

The Dyatlov Pass mystery spawned dozens of conspiracy theories, which have endured for 60 years. Lucy Ash traces the group's journey and tells their story through their diaries, photographs and letters.

Tatyana‘s mother was busy in the kitchen raising dough to make pies, when the phone rang. So, the 12-year-old schoolgirl picked up the receiver. An unfamiliar male voice asked if there were any adults at home.

“I handed the phone to my elder brother,” Tatyana says, “and he was informed that Igor was dead. The next day my parents were summoned to the university and the nightmare began.”

Today, Tatyana Perminova is a grandmother in her 70s, but she remembers that evening in 1959 as if it was yesterday. Tatyana’s mother had tried to stop her other brother Igor from going on a cross-country skiing trip with his friends, arguing that he was about to graduate and should get on with his thesis.

“But he pleaded with her,” says Tatyana. “Just one last time Mama! Just one last time! And indeed, it was his last time.”

Tatyana says that to her dying day, her mother never forgave herself for allowing her 23-year-old son to go on the expedition.

“She couldn’t ever come to terms with his loss - especially since it was such a terrible and incomprehensible death.”

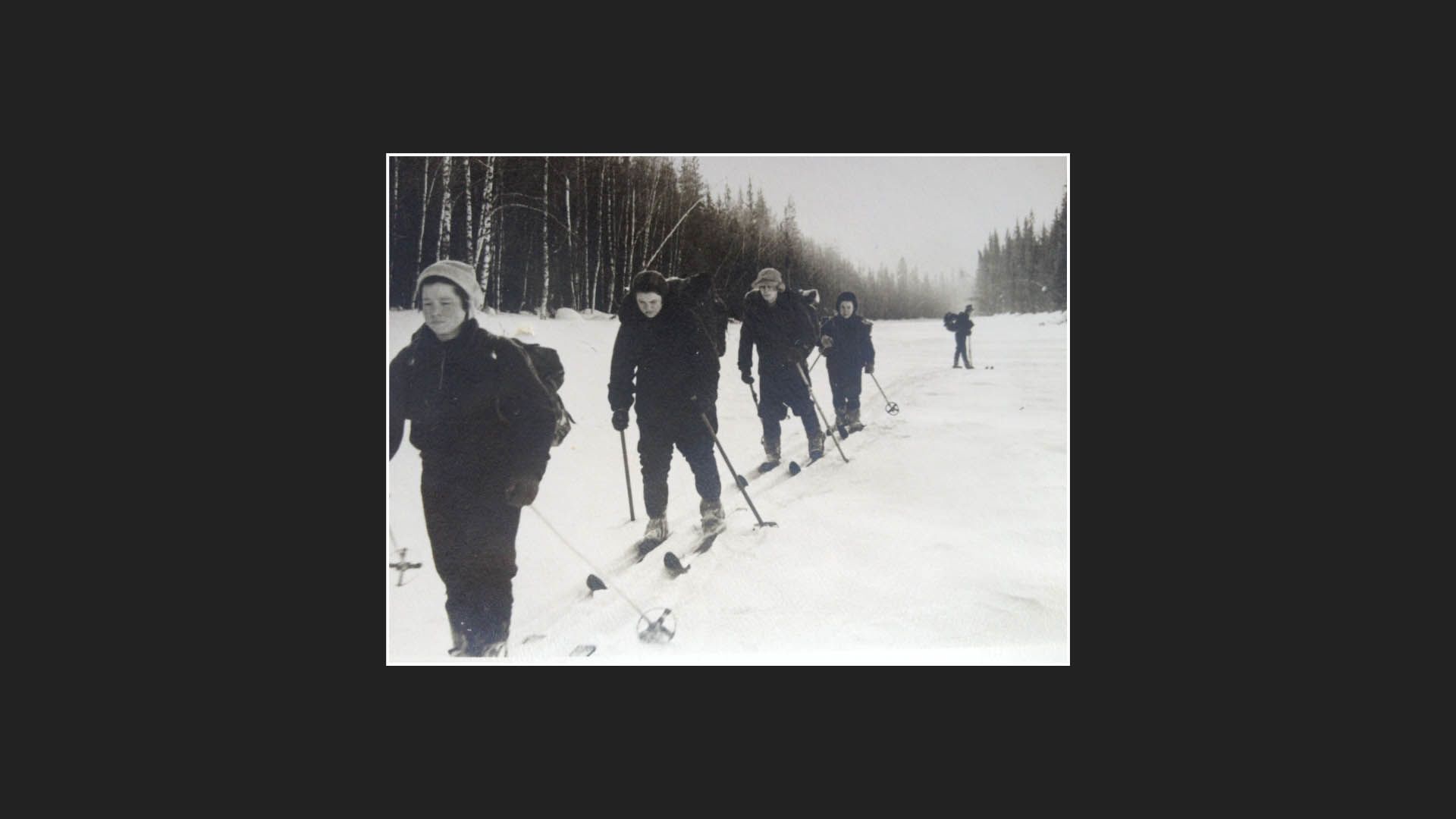

At the height of the Cold War, in the dead of winter, the group of 10 students led by Igor Dyatlov set out on a trip into the Ural Mountains – the range which divides Europe and Asia.

The skiers were all experienced, young sportsmen and women from the Urals Polytechnic Institute in Yekaterinburg, or Sverdlovsk as the city was called in Soviet times, but only one of them would survive.

Nine bodies were eventually found on a remote mountain with horrific, inexplicable injuries. Some were semi-clothed, two had missing eyes, and one’s tongue was missing.

The Dyatlov Pass mystery, as it’s become known, has spawned countless conspiracy theories over the past six decades. However, in February 2019, the Russian authorities made a surprise announcement - they were reopening the case in an attempt to get to the bottom of it once and for all.

The students’ trip was supposed to take three weeks. Igor - who was leading the trip - had promised to send a message to the sports club in Sverdlovsk as soon as his group was safely back at their base around 12 February. At first nobody was surprised they didn’t return on time. They had been delayed before because of bad weather.

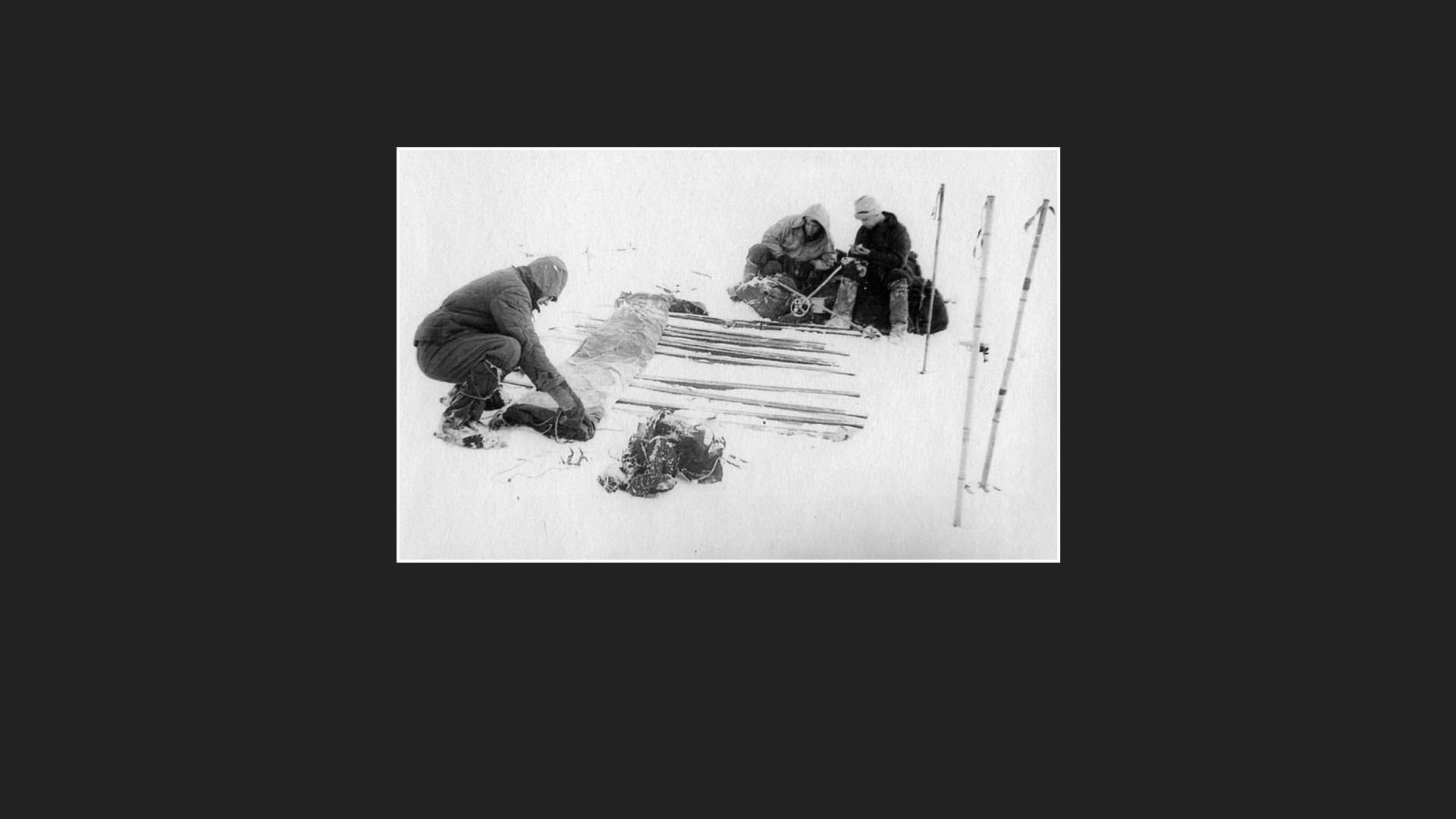

But by 20 February, their families became worried and raised the alarm. The university sent out a search party of student volunteers. Now in his 80s, Mikhail Sharavin, was one of them.

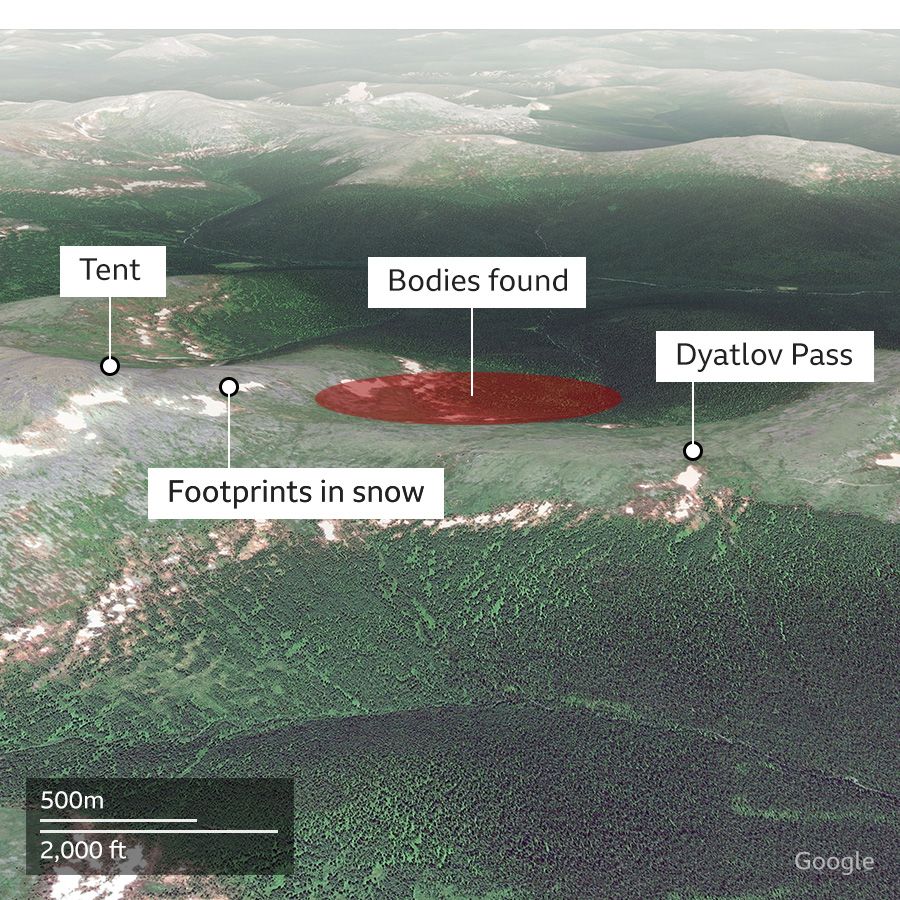

He was flown to the region by helicopter along with the other volunteers. They split into smaller groups and followed some ski tracks which came to an end at the edge of the forest before climbing up the pass.

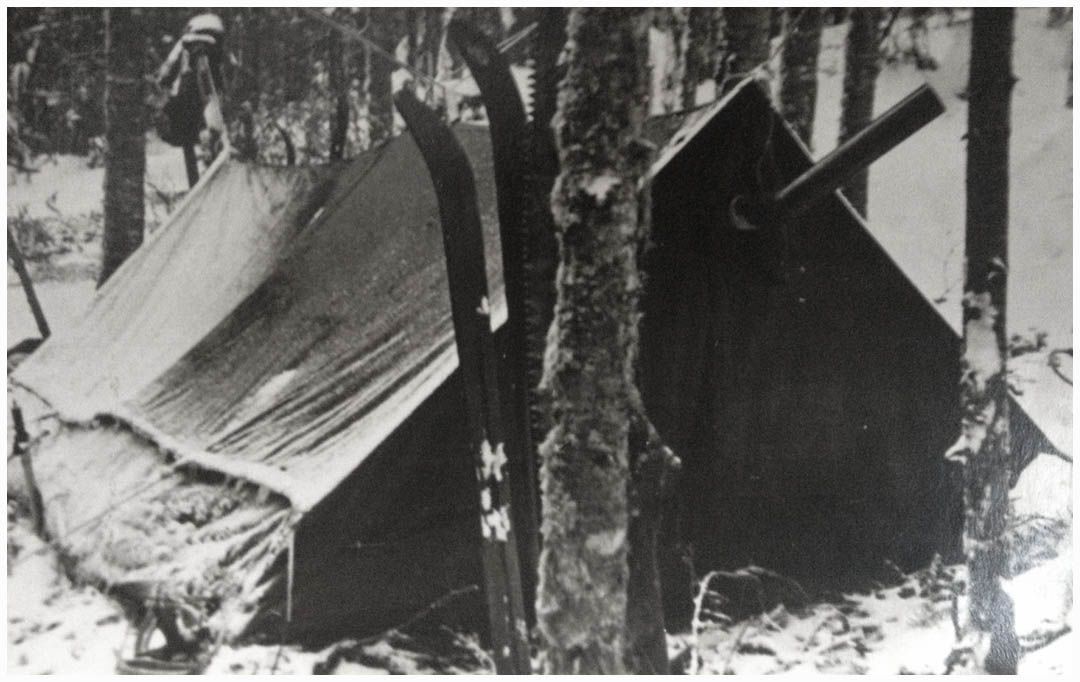

“We had gone about 500 metres when on the left I saw the tent,” says Sharavin. “Part of the canvas was poking out but the rest was covered in snow. I used an ice pick lying nearby to uncover the entrance.”

Inside, he and another rescuer found a blanket and some rucksacks lined up neatly and a pile of boots in one corner. There was also the route map, official papers, money, and a flask of alcohol.

Next to that, he spotted a plateful of salo - white pork fat - a Slavic delicacy and the sort of high-calorie food that hikers take with them into the mountains. “It was sliced up as if they were getting ready to have supper or something and didn’t have time,” says Sharavin.

It was then that he noticed the tent had been slashed open from the inside with a knife. Maybe they were in a desperate hurry to get out, he thought, but why? Then he came across something even stranger.

Just outside the tent, he saw frozen footprints made by eight or nine people who were wearing socks, a single boot or were barefoot. The tracks continued for five to 10 metres and then they disappeared.

Sharavin and his friend were dumbfounded. They wondered what on earth could have made the students leave their shelter semi-clad when it was at least -20C outside.

They immediately skied downhill to tell the others in the search party what they had found. Later, when they sat around the campfire for their evening meal, Sharavin produced the flask of vodka that he’d found in the tent and proposed a toast to the health of the Dyatlov group.

“We shared it out between us – there were 11 of us, including the guides,” he recalls. “We were about to drink it when one guy turned to me and said, ‘Best not drink to their health, but to their eternal peace.’”

A cross-country skiing trip

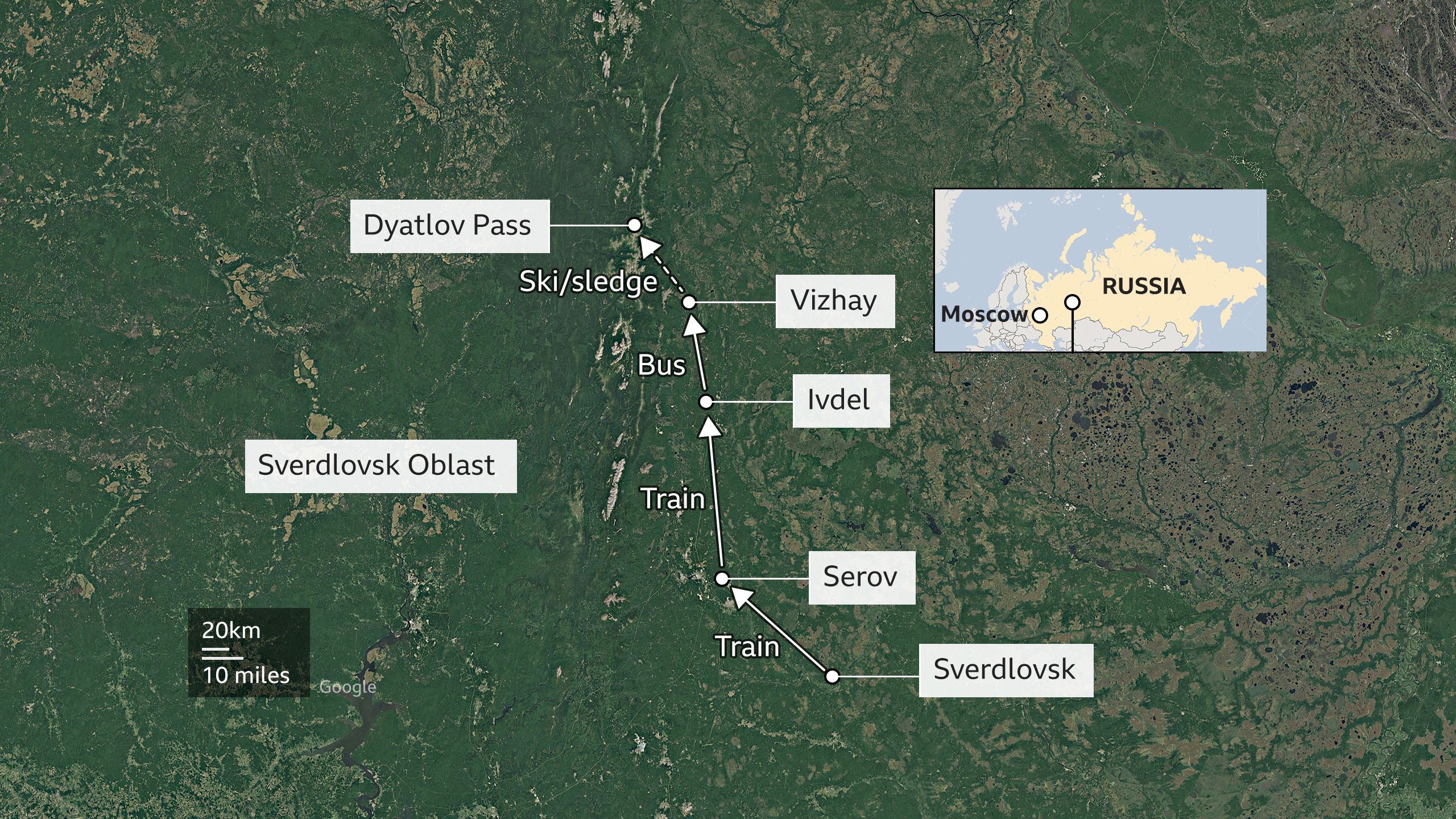

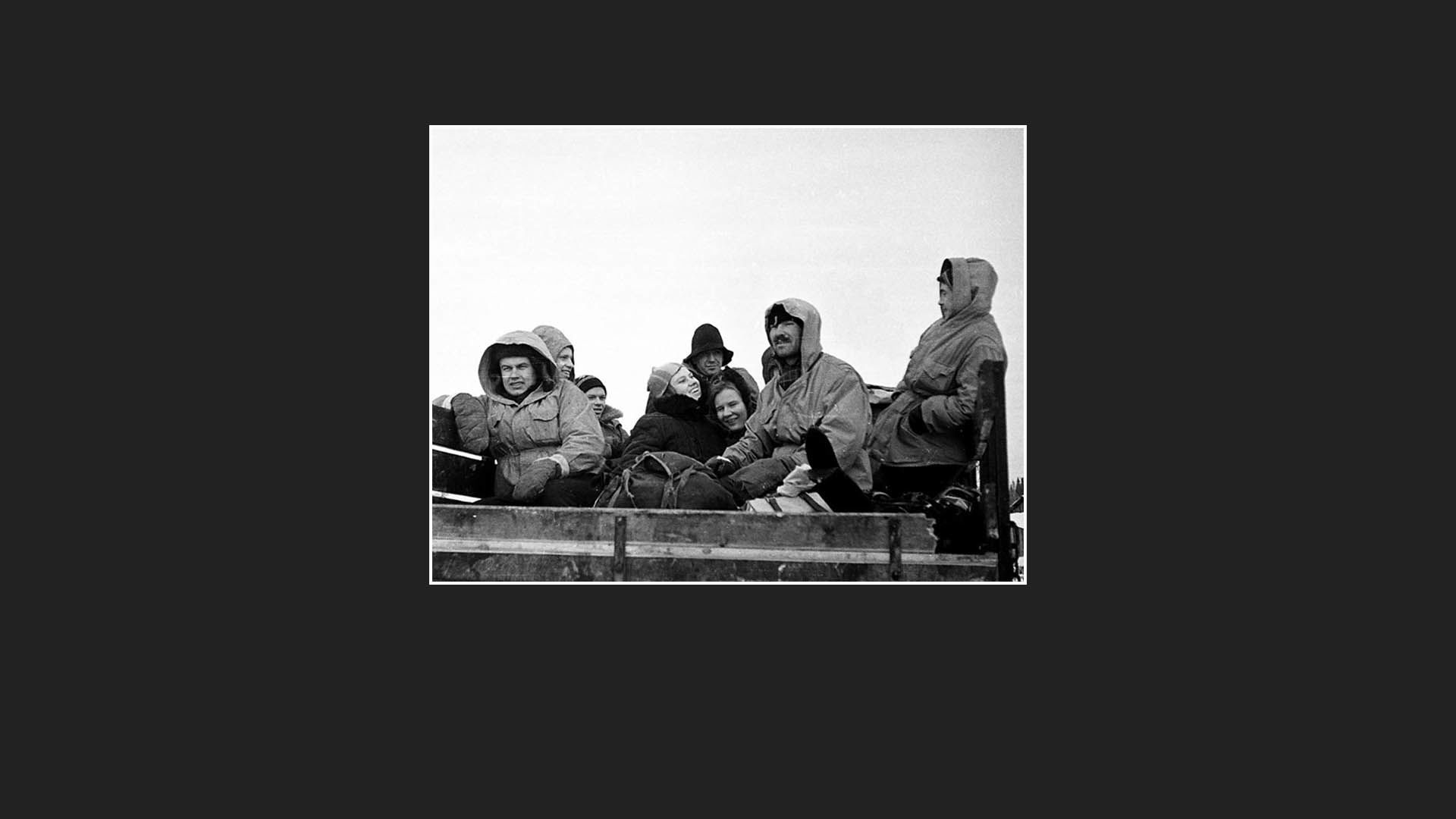

On the evening of 23 January 1959, the group of students boarded the sleeper train from Sverdlovsk, just east of the Ural Mountains.

To get a better idea of what might have happened to the students, I decide to trace their journey. Today, Yekaterinburg is Russia’s fourth-largest city and was a host city in the football World Cup.

On the spot where Tsar Nicholas II and his family were murdered in 1918 after the Revolution, there’s a shiny new Byzantine church. On the other side of the Iset River, a modernist shrine to one of the city’s most-famous sons - Russia’s first President, Boris Yeltsin.

But the train to the north seems untouched by time. A grumpy, uniformed conductor peers at my ticket and waves me on board. At one end of our carriage, there’s a battered samovar providing water for much-needed hot tea. As I spread the sheets on my bunk bed, I imagine the students doing the same 60 years ago, and chatting excitedly about their trip.

Listen: The Dyatlov Pass mystery

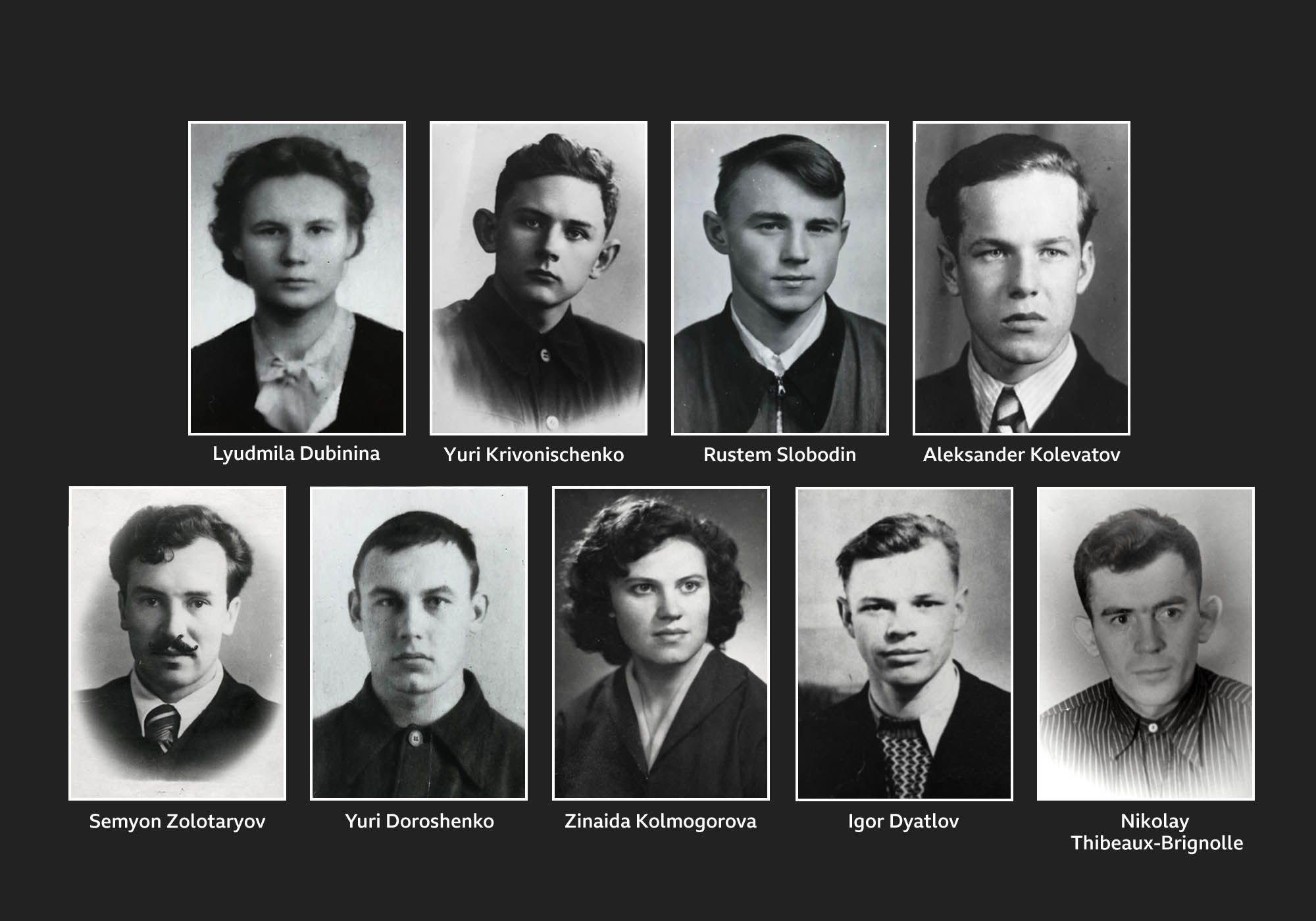

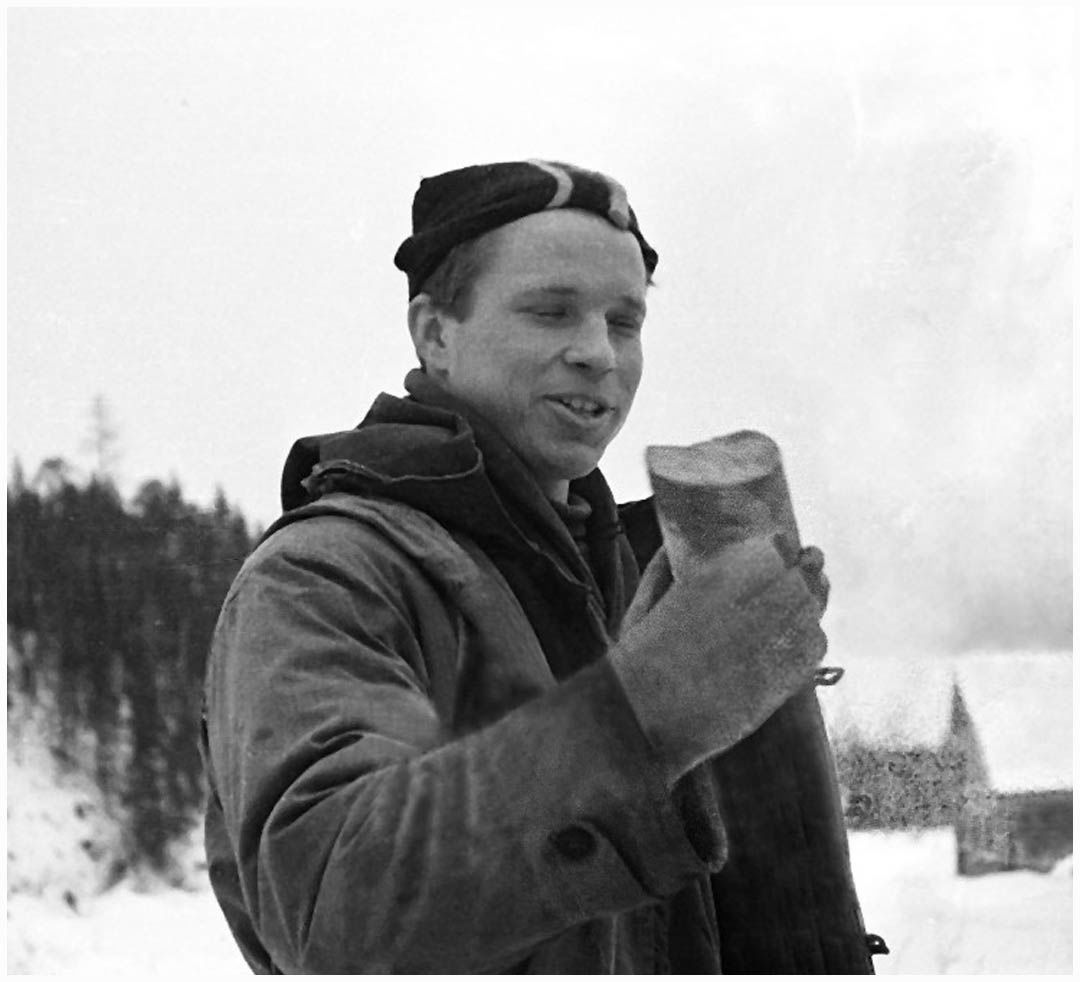

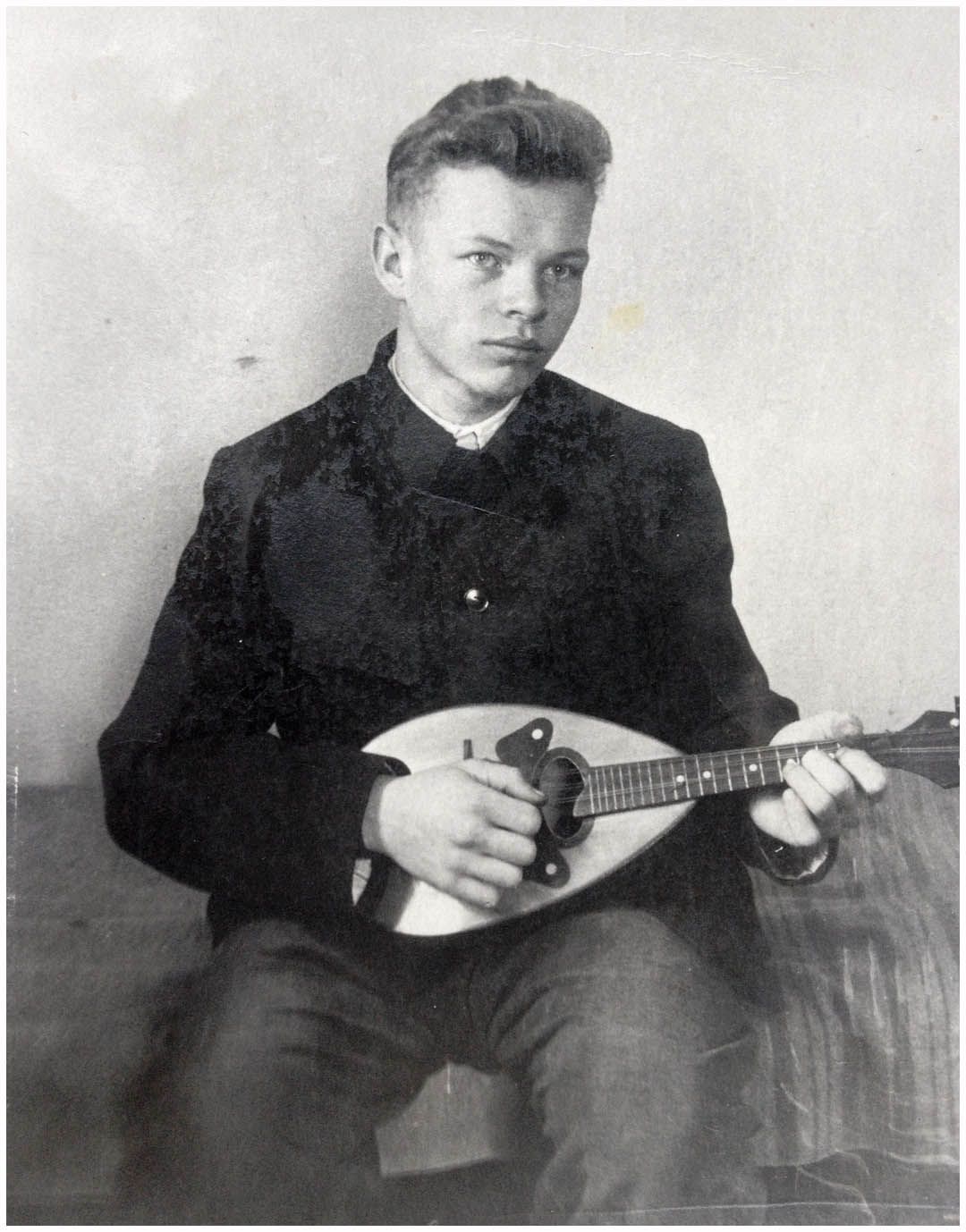

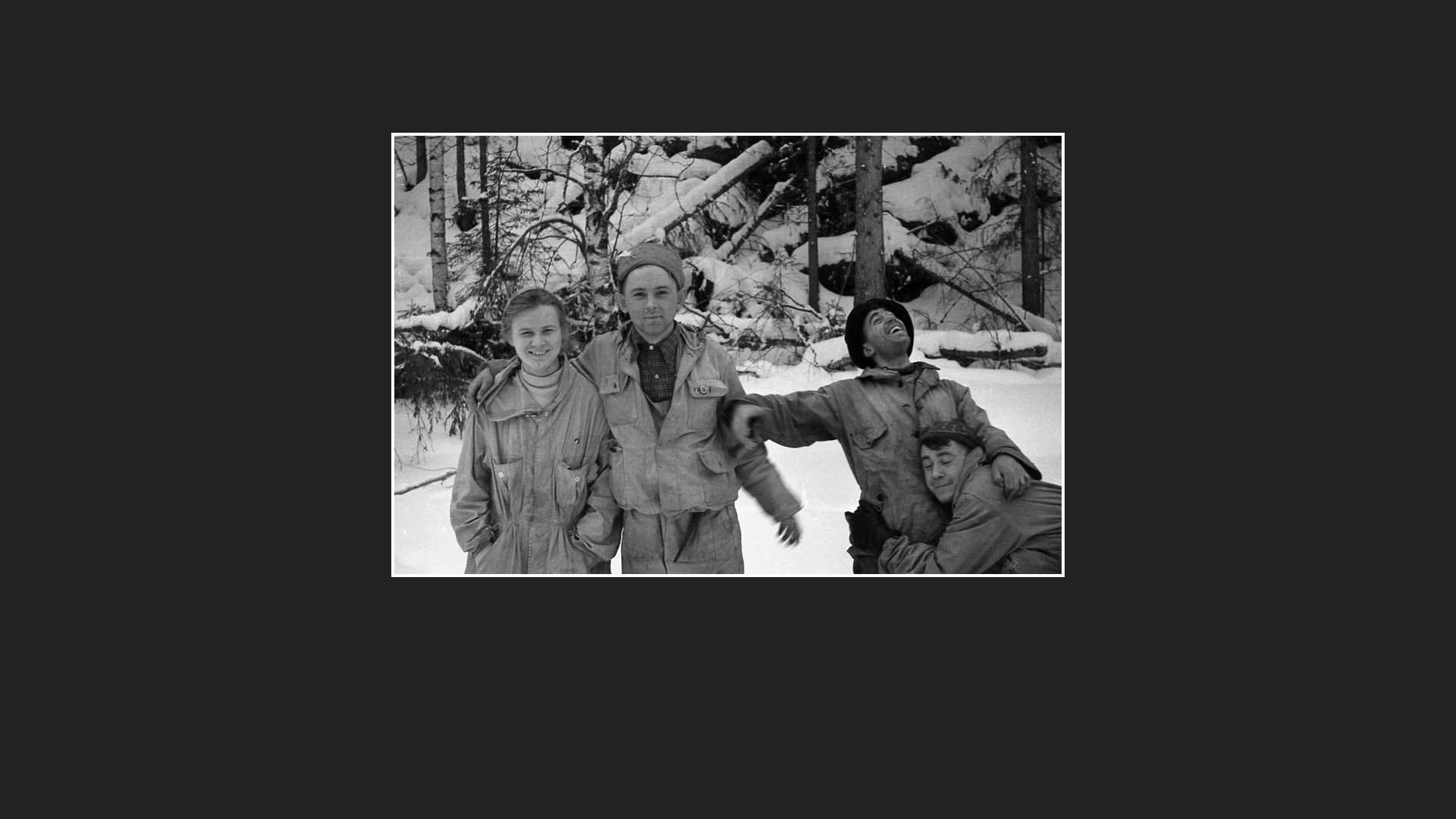

The party consisted of eight men and two women. Igor, the leader, was a fifth-year radio engineering student and one of the most experienced athletes in the group. There was also Zinaida Kolmogorova, 22, from the same faculty, Yuri Doroshenko, 21, who was studying power economics, Alexander Kolevatov, 24, studying nuclear physics, Yuri Krivonischenko, 23, Rustem Slobodin, 23 and Nicolas Thibeaux-Brignolle 23 - all engineering students. Lyudmila Dubinina, 20, and Yuri Yudin, 22, were both studying economics. Semyon Zolotaryov, a 38-year-old sports instructor who had fought in World War Two, was the odd one out.

We can trace the students’ journey, up to a certain point, through their diaries, photographs and letters.

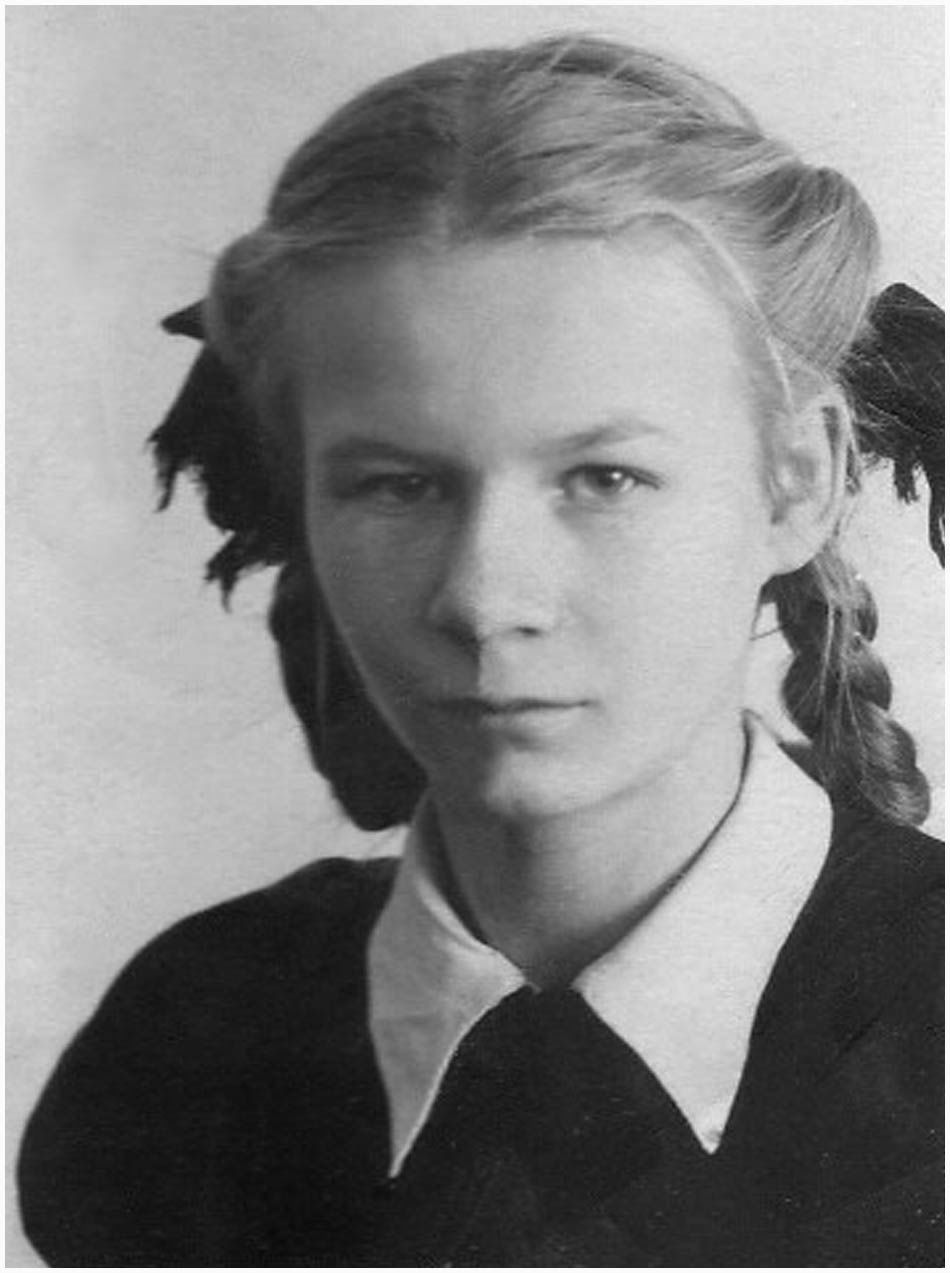

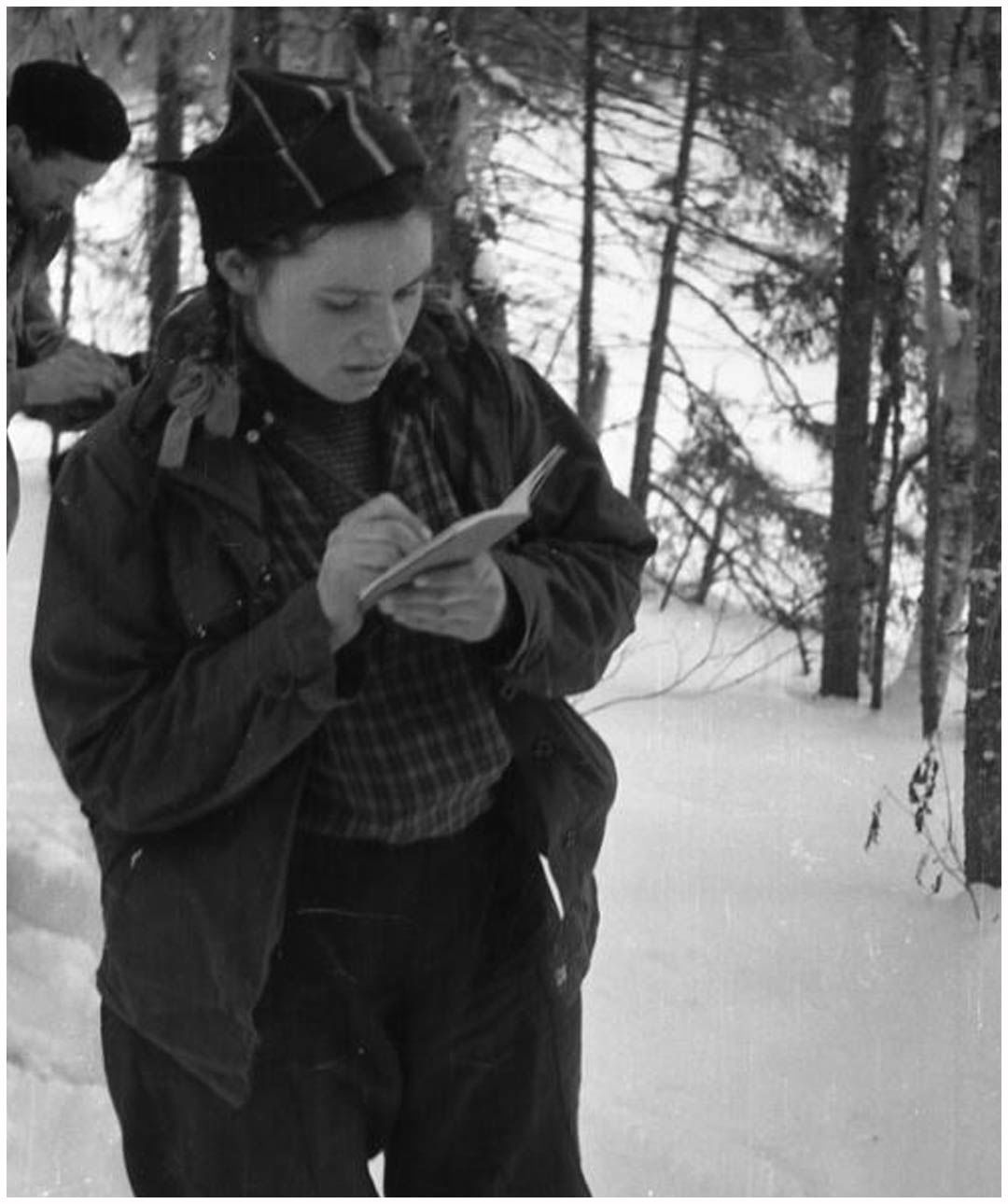

Lyudmila Dubinina, the youngest skier, had a reputation as a stern, somewhat humourless member of the Komsomol - the Young Communists. But reading her diary, it sounds as if she was enjoying the adventure and beginning to loosen her neat blonde plaits.

“In the train we all sang songs accompanied by a mandolin,” she wrote. “Then out of the blue, this really drunk guy came up to our boys and accused them of stealing a bottle of vodka! He demanded it back and threatened to punch them in the teeth. But he couldn’t prove anything and eventually he got lost. We sang and sang, and no-one even noticed how we slipped into a discussion about love… and kisses in particular.”

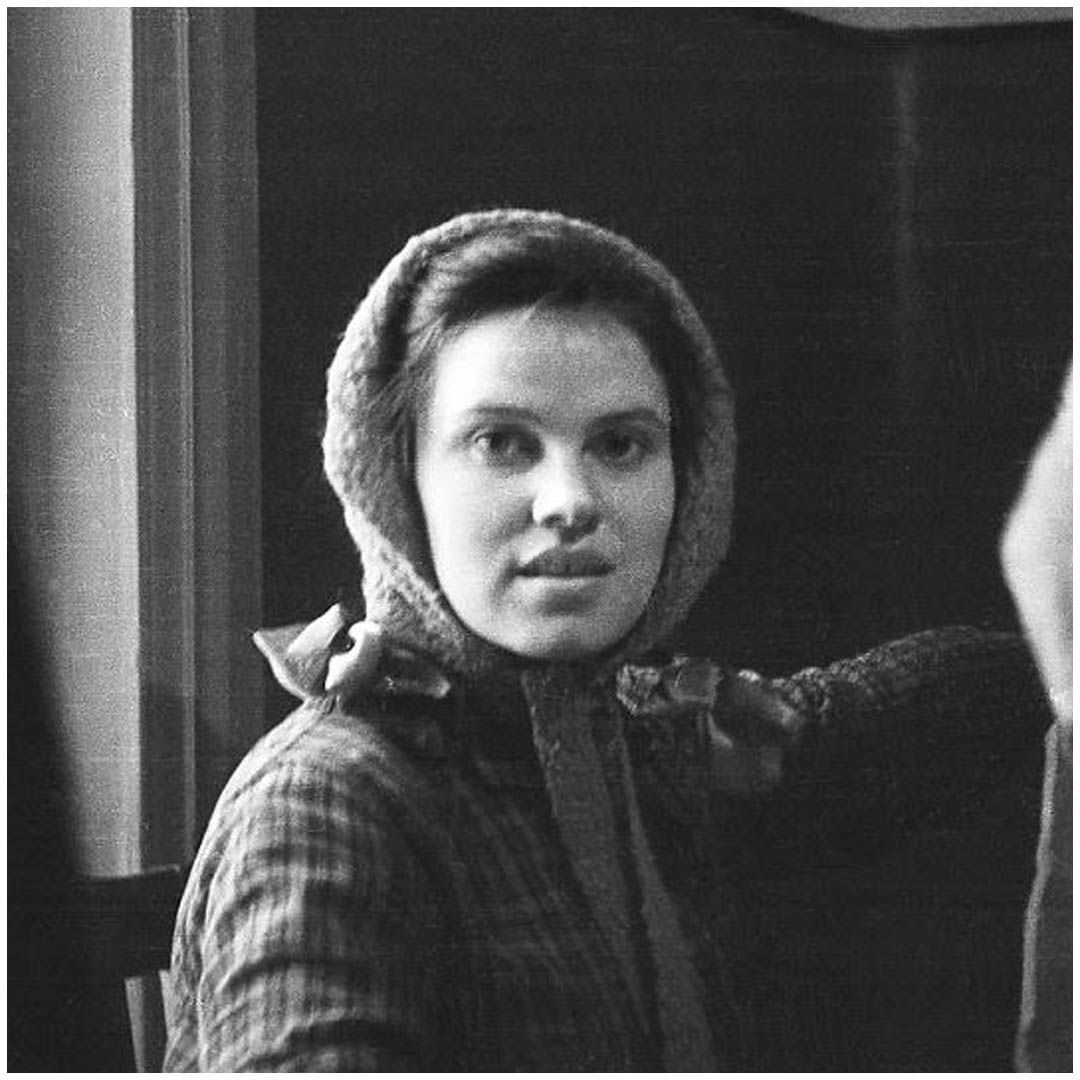

Zinaida Kolmogorova, outgoing, energetic and one of the university’s most popular students, wrote to her family from the city of Serov, a stop along the route.

“We are going camping, ten of us and it’s a great bunch of people. I have all the warm clothes I need, so don’t worry about me. How are you? Has the cow calved yet? I love her milk!”

She asked about her father’s health, her mother’s work and urged her younger sisters to study harder at school. Zinaida and Igor sent their last letters home from the post office in a small settlement further along the route called Vizhay.

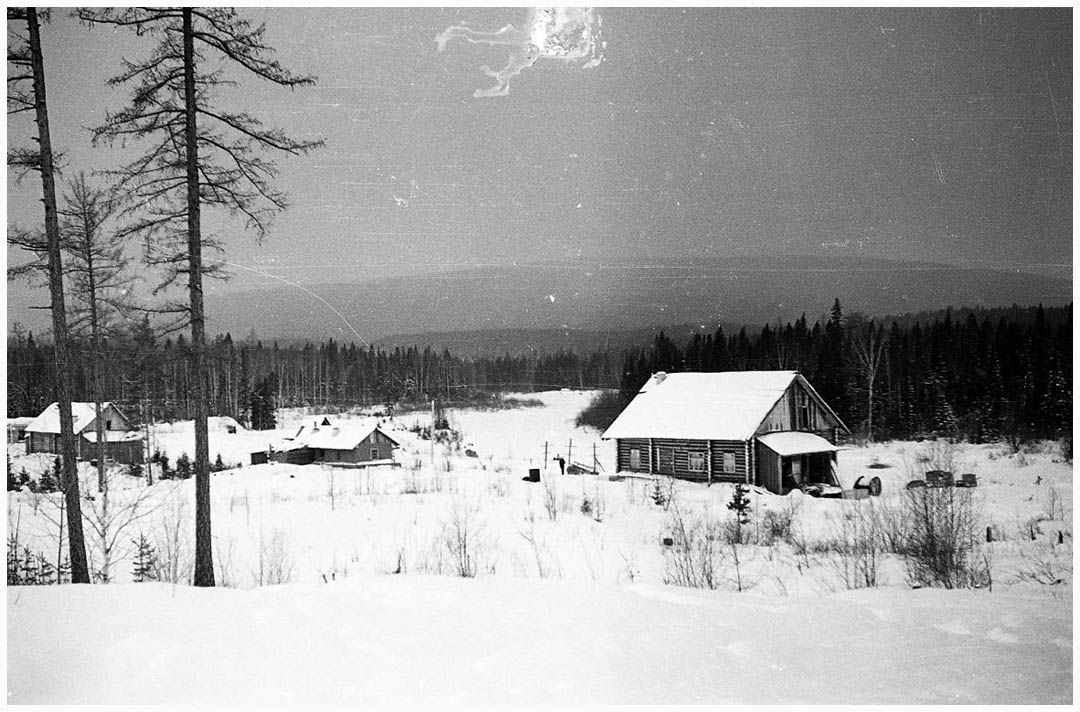

They spent the night there on 25 January, before getting a lift by truck to a logging base called the 41st settlement.

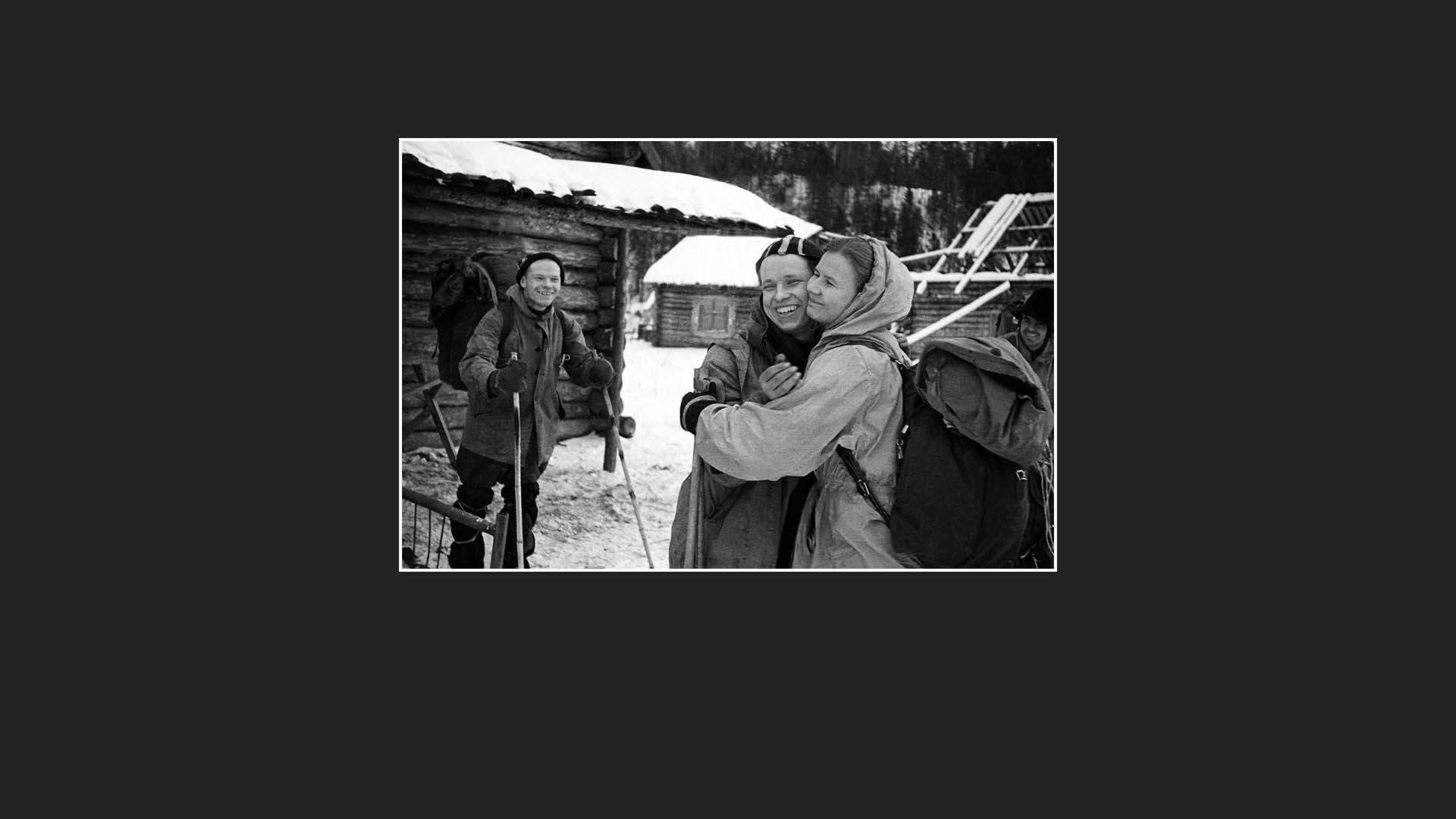

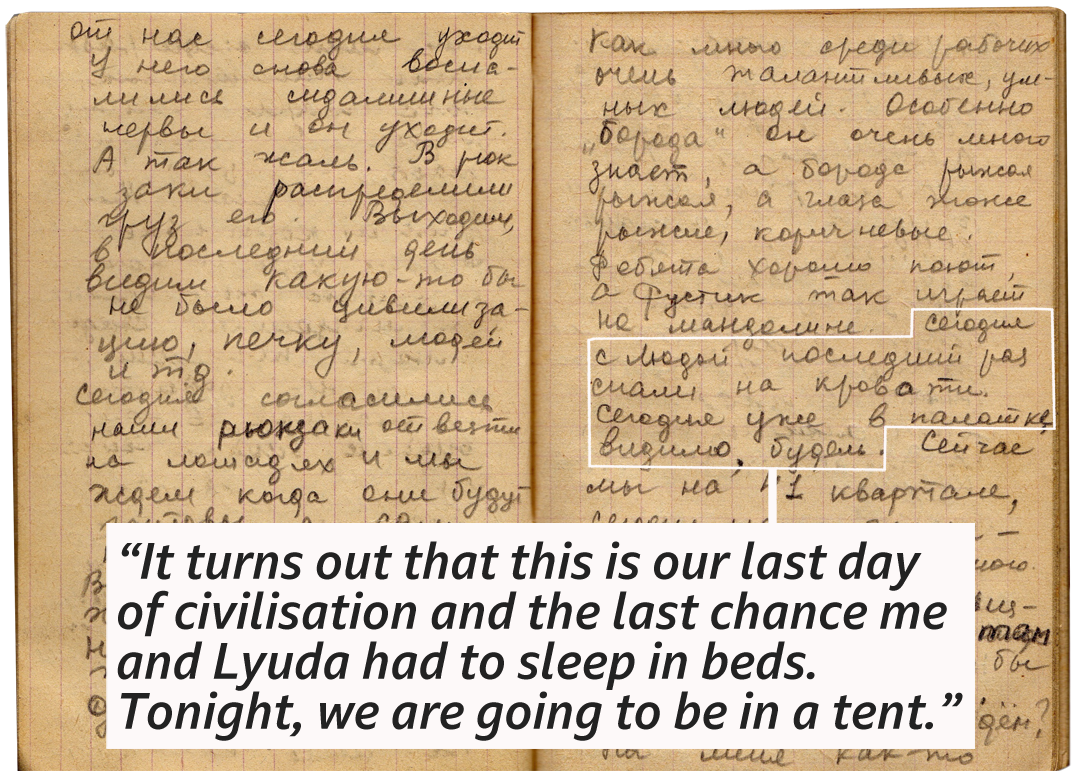

The students enjoyed chatting to the lumberjacks around a warm stove and discussing their favourite films. Zina wrote another entry in her diary.

“It turns out that this is our last day of civilisation and the last chance me and Lyuda had to sleep in beds. Tonight, we are going to be in a tent.”

Since I’m following in the footsteps of the students, I should be on cross-country skis, but I’m taking the easy way out on a snowmobile. It’s an uncomfortable ride because the snow is heavy, and the track is rutted so we can only travel at about 8km (five miles) per hour.

I think of the students who were weighed down with their rucksacks as they followed the river valley and the hunting tracks of the Mansi – the indigenous people who live in this area.

The group hired a horse-drawn sled to carry their supplies for the last 15 miles to the abandoned North-2 mining settlement. The going was tough, and the strain became too much for one member of the group.

“Yura Yudin is leaving us today,” wrote Zinaida in her diary.

“His sciatic nerves have flared up again and he has decided to go home. Such a pity. We distributed his load in our backpacks.”

The economics student felt so unwell that he returned on the sled. He was sorry to leave his friends but it was a decision that saved his life.

The Soviet golden age

Igor Dyatlov and his fellow students belonged to a more optimistic generation than their parents who had suffered so much in the purges of the 1930s and then in WW2.

There was a whiff of freedom in the air after decades of repression under Joseph Stalin. The students had access to some foreign literature, music, and films. Lyudmila Dubinina was thrilled to see a romantic Austrian musical about ice skating when the group stopped for the night in Vizhay.

“We are extremely lucky!”, she wrote in her diary on 25 January. “Symphonie in Gold was showing at the village club. The image was a bit fuzzy, but that didn’t spoil our pleasure at all. Yurka Krivonischenko, sitting next to me, was smacking his lips and oohing with delight. This is real happiness, and it is hard to put into words. The music is just fabulous! The film really lifted our spirits. Igor was unrecognisable. He tried to dance, and even started singing: 'O Jackie Joe' [a song from the film].”

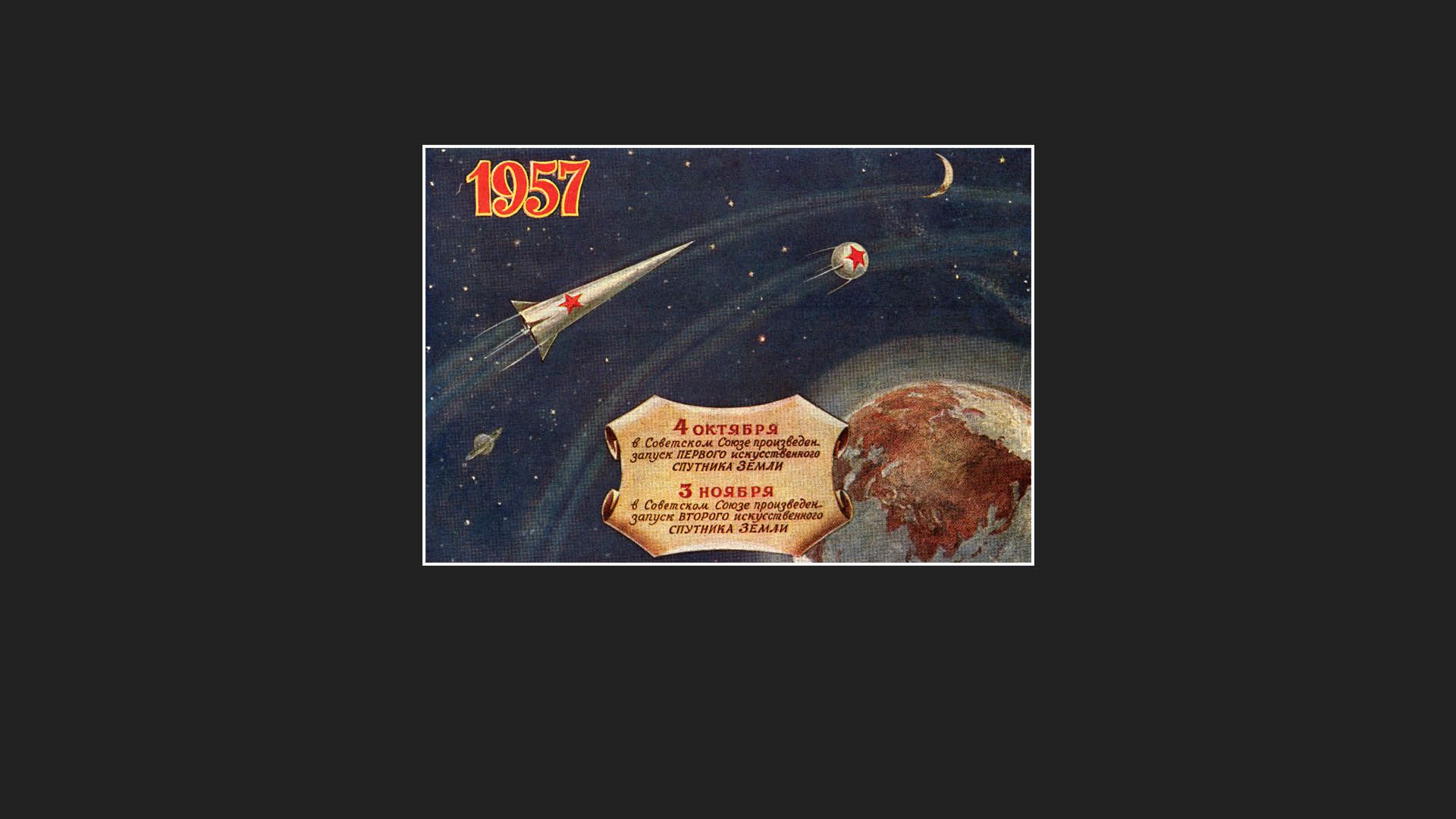

What’s known as “the thaw” under Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev opened up the Soviet Union to some economic reforms, international culture and sports competitions. Above all though, it was the golden age of Soviet science.

Tatyana was in awe of her brilliant older brother Igor. She tells me he was determined to get a place at the prestigious Urals Polytechnic Institute. Boris Yeltsin had studied engineering there and became Communist party boss of the region before he became Russia’s first post-Soviet president.

Competition for a place was fierce, and on a hot summer day Igor was confronted by a three-man selection panel. As sweat trickled down his face, an unimpressed professor turned to Igor: “If you’re so clever,” he snapped, “why don’t you fix our broken fan?”

Unperturbed, Igor asked for a screwdriver. “He took it apart, explained it just needing oiling from time to time and switched it on,” laughs Tatyana. “And of course, he got his place.”

Igor was a skilled mechanic but set his sights much higher. It felt as if anything was possible after the USSR launched Sputnik in 1957 – the first man-made satellite to orbit the Earth. The taunting beeps from that tiny aluminium sphere sent a clear political signal - the Soviet Union was hurtling ahead in the space race.

Although US President Dwight Eisenhower initially dismissed the Sputnik as “a small ball in the air”, it was soon clear the Americans were on the back-foot.

Igor made his own telescope and would climb on the roof of his house with his younger sister and her friend to look at the satellite.

“It was so magical,” she recalls. “Everyone believed that after he graduated, Igor would go into cosmonautics. It was a brand new industry, and he wanted to be part of it.

“Imagine, the war had just ended, and the country was utterly devastated, everything had to be restored, specialists were needed,” Tatyana adds.

“Igor and his friends wanted to study serious subjects – engineering, physics, complex technical topics. Everybody wanted to work hard for their homeland. They were real Soviet people, in the best sense of the word.”

Death mountain

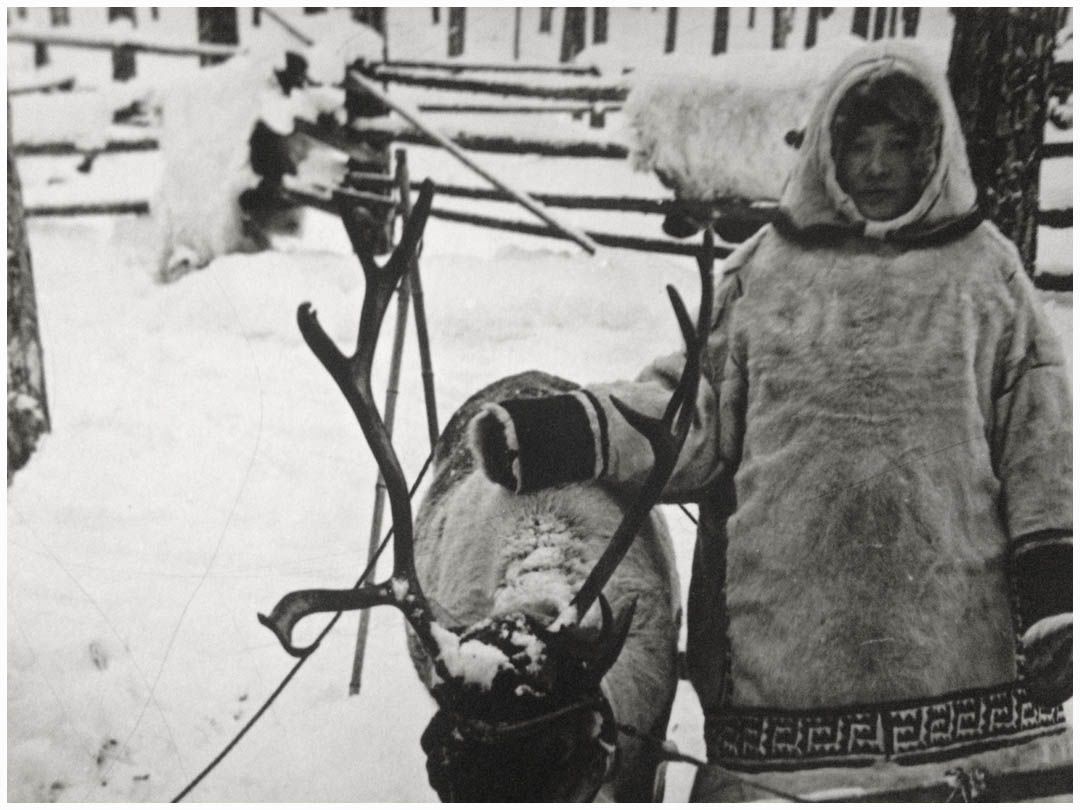

After Yura Yudin left the group, the students continued towards their goal: Mount Ortorten. Our guide, Alexander, says that the mountain’s name means “don’t go there” in the language of the Mansi, the indigenous reindeer herders who have inhabited the region for hundreds of years.

But in the 1950s, the Mansi weren’t the only people living here. After travelling for hours on our snowmobiles past icy swamps, fields and forests, we stop at a crossroads. Alexander takes us down a path to a series of badly dilapidated houses, half-buried in snow. It is not an abandoned village, but the remains of lodgings built for prison guards.

There was once a network of prison camps in the north Urals known as Ivdel-lag, where 30,000 inmates built roads, cut and processed timber and laboured in makeshift factories. The camp had a reputation as one of the most atrocious and violent in the entire gulag system. Yet few tried to escape because of the remote location and the harsh climate. I stare at the gaping windows and missing roofs and feel a shiver down my spine.

Igor Dyatlov’s group skied along the nearby Auspiya River before the final ascent.

“There was sun in the morning, now it’s very cold,”

Zinaida wrote in one of her last diary entries.

“All day long we followed the river. At night we’ll camp on a Mansi trail. I burned my mittens and Yura’s jacket at the camp fire – he cursed me a lot!”

Zinaida was once Yura Doroshenko’s girlfriend but he broke things off with her, and a letter to a friend discovered months later, revealed she was nervous about going on the trip with him.

“I really don’t know how I’ll feel. It’s really hard, because we are together and yet we’re not together."

She had fallen in love with him during a previous expedition when he chased off a brown bear with a geologist’s hammer.

On the snow mobiles, we are now on the final leg of our journey, going on a steep track uphill. We pass pine trees and birch trees laden down with snow. I also notice some animal footprints. There are reindeer, wolverines and lynx in these forests. The sky is blue, but our guide warns that the weather is unpredictable and can change at any minute.

Further on, we rise above the forest where there are just a few dwarf pines and flinty rocks poking through the snow. We are on the eastern slope of Kholat Syakhyl, which (I’m told) means Mountain of Death. The swirling winds sting our faces and clouds descend quickly, limiting vision to only a few metres.

Yet on the night of 1 February, for some inexplicable reason, the students pitched their tent here. Our guide Alexander agrees that it seems like a strangely exposed place to camp. “Maybe they had climbed up this far and didn’t want to lose any height,” he says.

He adds that their tent was erected in a shallow pit, which had presumably been dug to shelter the group from the wind.

When Mikhail Sharavin from the search party eventually stumbled on the tent, nearly a month later, it was 300 metres from the top of the mountain.

Today, Sharavin is an 83-year-old widower living in an isolated, ramshackle house an hour’s drive outside Yekaterinburg. He is skinny, bald, and hollow cheeked but his eyes light up with pride when he tells me how he found the tent.

One tent pole was sticking up above the snow and there was a flashlight resting on top of the canvas which remarkably still worked when he switched it on.

The following day on 27 February, his worst fears were confirmed when he and some others in the rescue party found the first of the bodies.

“We approached a cedar tree,” says Sharavin, “and when we were 20 metres away, we saw a brown spot – it was towards the right of the trunk. And when we got closer we saw two corpses lying there. The hands and the feet were reddish-brown.”

One of the two bodies was Yura Doroshenko. Next to him was Yuri Krivonischenko, who played the mandolin and loved telling jokes. He had bitten off a piece of his own knuckle. Both men were stripped to their underwear.

Closer to the tree, the search party saw the remains of a camp fire and thought it looked as if somebody had climbed the tree to break off the lower branches to use as kindling.

Igor was found next. He was dressed but shoeless and lying face down in the snow, hugging a birch branch. Zinaida Kolmogorova lay nearby and from the position of her body it seemed as if she had been desperately trying to scramble back uphill towards the tent.

There was a long bright red bruise on the right-side of her torso, which looked as if it was made by a baton.

My guide Alexander tells me, officially, it was stated that the skiers had died of hypothermia and frostbite, but some of the other bodies had serious injuries that had nothing to do with them being too cold.

Rustem Slobodin, a long-distance runner and one of the shyest in the group, was found on 5 March with a fractured skull. His body was better dressed than the others found so far. He wore a long sleeve undershirt and sweater, two pairs of trousers, four pairs of socks, and one felt boot on his right foot. His watch had stopped at 08:45.

The mystery deepened when the remaining four bodies were found in a ravine in May, nearly three months later, once the snow had melted. Nikolai Thibeaux-Brignolle, the son of a French communist repressed by Stalin, had a fractured skull. Aleksandr Kolevatov, the nuclear physics student who had worked at a secret institute in Moscow, had a wound behind his ear and an oddly twisted neck.

Lyudmila Dubinina, the ardent young communist and Semyon Zolotaryov, the oldest member of the group, had suffered multiple broken ribs. He had an open wound on the right side of his skull, which exposed the bone. There was another gruesome detail - both had empty eye sockets, and Lyudmila's tongue was missing.

Back in Sverdlovsk, Tatyana did not attend her brother Igor’s funeral – her parents thought it would be too traumatic for her.

“But I saw a photo of him in the coffin afterwards,” she says. “It was just terrible. He looked completely different to what he looked like before. My mum said that she only recognised him from the gap between his teeth. His hair was grey.”

She says that the students’ parents believed that the deaths were somehow related to the military.

“What went on up there is hard to say. The families were told, ‘You will never know the truth, so stop asking questions.’ So what could we do? Don’t forget, in those days if they told you to shut up, you would be silent.”

Why they died

Since the students’ bodies were found with strange injuries, people could not accept that they had simply perished from hypothermia and immediately questioned what – or who – was responsible.

At the time of the deaths, accusing fingers were initially pointed at the only other people living in the region, the Mansi. One of 45 indigenous peoples living in Russia, the Mansi have survived over the centuries by hunting, fishing and reindeer herding. I went to meet one of the local tribe leaders.

Valery Anyamov, a rugged man in his 40s, works as a forest warden and lives in the settlement of Ushma, not far from the decaying prison camps. Valery’s dad Nikolay helped to look for the missing students, but soon his community became the prime suspects.

“Soviet investigators were convinced we Mansi must have killed them,” Valery says. “So many people around here were arrested and a woman from another village, who is no longer with us, used to say that the secret police tortured them. I don’t know if that is true, but they were certainly interrogated for weeks.”

Eventually, the Soviet authorities were unable to find any incriminating evidence and flew their helicopters to the Mansi villages to ask once again for help. “Thanks to our guys, the remaining four skiers were found in May,” adds Valery. Under the melted snow, a Mansi hunter discovered fragments of clothing including part of Lyudmila’s sweater, which eventually led them down to the ravine.

Suspicions still linger about the Mansi’s possible involvement. One book published in 2015 suggests that some Mansi hunters were high on the magic mushrooms used in shamanic rituals, and they went berserk when they found that the students had veered onto sacred Mansi land.

Valery dismisses such theories.

“If any of our people had been involved in that crime,” he says, “they would have thrown us all into prison because it was a cruel time. In those days people were executed by firing squad without investigation or trial.

“All that stuff about bad places and areas of negative energy was invented by the mass media.”

But meeting me, a journalist, Valery takes the opportunity to make a small correction. Mount Ortorten does not mean “Don’t Go There”, as my guide and many others claim. He tells me it actually means “Mountain with Swirling Winds” and that it was a mistranslation – or someone wanted to invent a spine-chilling name to ramp-up the mystery surrounding the tragedy.

So what does he think happened? He believes that there is “a technological explanation” for the students’ deaths and suggests that I talk to his 80-year-old mother, Sanka. She is sitting by the stove in their small wooden home, wearing embroidered boots of reindeer fur.

Sanka is one of a shrinking number of people alive at the time of the incident. One evening in February 1959 she was out collecting firewood when she noticed something strange in the sky.

“We were coming back from the forest and we could see the village ahead of us,” she says. “This bright, burning object appeared. It was wider at the front, and narrower at the back, with a tail, and there were sparks flying off it.”

Perhaps it was a comet, but Sanka says the village elders, who also witnessed this burning object, warned it was a bad omen - something harmful.

So were the mysterious lights in the night sky celestial or man-made?

After meeting the Mansi, I make the long journey back to the city of Yekaterinburg, where the students had attended university. Yuri Kuntsevich, who has made it his life’s mission to keep the memory of the students alive, lives not far from the city centre.

Like Igor’s sister Tatyana, he was just 12 when the tragedy occurred. But unlike her, he attended some of the students’ funerals as he lived opposite the Mikhailovskyie cemetery.

“There were rumours flying all over the city that these students had wandered into some kind of tests or experiments,” he tells me in his flat, which he has turned into a mini-museum devoted to the Dyatlov group.

“The coffins were open,” says Yuri, “and I could see that the skin on their faces was a weird colour – the colour of bricks. There was nothing in the newspapers, but everyone was talking about it. We thought it must be some kind of state secret.”

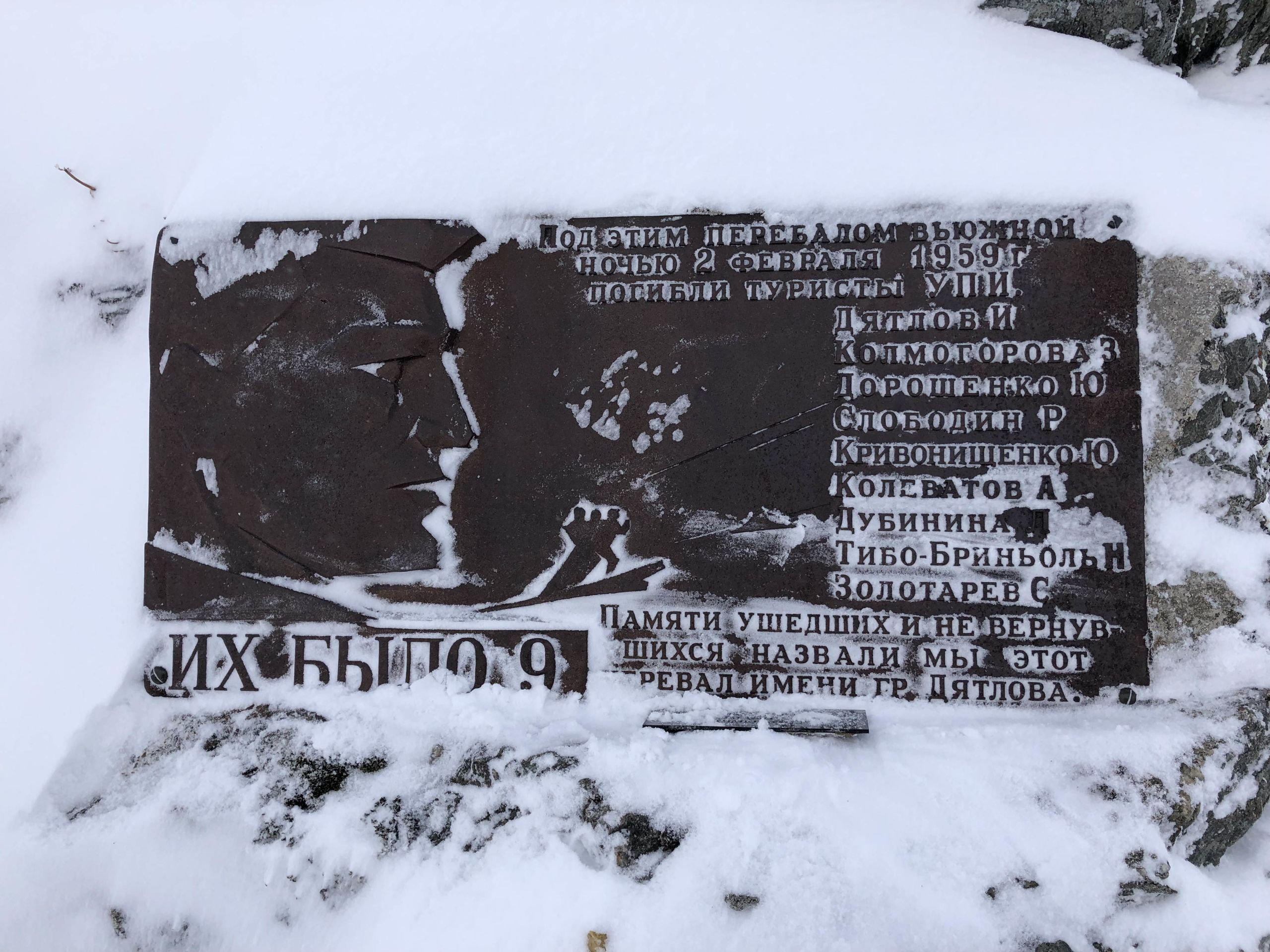

Growing up, Yuri gradually became more and more fascinated with the case. He retraced the steps of the hikers and used to go each year on a pilgrimage to the place now known as the Dyatlov Pass – named after Igor, the group’s leader - and lay flowers on a granite memorial dedicated to the students.

His living room is like a shrine with large oil portraits on the walls of each of the dead students. Shelves and drawers are crammed with books, papers, photographs and personal possessions they once owned - from compasses to maps, penknives, camping stoves and school reports.

Yuri believes the students were victims of a military experiment, and that they died on the spot. He tells me – with the help of a hastily drawn diagram - that later the corpses were flown back to Mount Kholat Syakhyl by helicopter and rearranged to make it look as if they had frozen to death.

The Soviet military were capable of inhuman acts, but would they really take the trouble to collect corpses, only to later dump them onto a mountain side? Surely there were simpler ways to make dead bodies disappear.

I couldn’t get a straight answer out of Yuri or any real evidence to back up his theories, but he is certainly not alone in believing there has been a state-sponsored cover-up. Even Russia’s first President, Boris Yeltsin, who studied at the Urals Polytechnic Institute just a few years before Igor Dyatlov, felt there was something very odd about the case.

Oleg Arkhipov, who lives in the nearby city of Tyumen, has written three books about the Dyatlov Pass Incident. He is a devotee of Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes. Oleg turns up to a meeting at our hotel wearing a deerstalker hat just like the famous literary detective.

He has unearthed some interesting documents after making friends with the former prosecutor, Lev Ivanov, who first investigated the deaths and led the official inquest in 1959.

Oleg explains that at first the prosecutor was very diligent and appeared determined to solve the case. He asked the forensic experts detailed questions about exactly what had caused the students’ severe injuries and he was told they had been subjected to “something like an explosion wave”.

But he says that suddenly Ivanov appeared to have lost interest in the case, and closed it because of pressure from his superiors.

“If he had refused,” Oleg tells me, “he would have been sent to the Ivdel region not as an investigator, but as a prisoner. In those days, opposing the party didn’t just spell the end of your career.

“That was, unfortunately, the reality of our country.”

And yet elements in this case are so puzzling and contradictory that even the Soviet authorities weren’t sure how to describe what happened.

“They thought about the best way to explain these deaths,” says Oleg, “and decided to blame ‘an insurmountable force of nature’. Of course, everyone understands this phrase differently. It could describe a hurricane, or a tornado - but not necessarily.”

The investigator, Ivanov, was transferred to an obscure town in the Republic of Kazakhstan and the affair was buried for three decades. He only found the courage to speak out when the Soviet Union began falling apart.

In 1990 Ivanov gave an interview to a newspaper in which he admitted that he’d been amazed by the results of the autopsy on the students, and that he’d received several reports about balls of fire in the sky. But he’d been ordered to classify his findings and forget about them.

In the newspaper article Ivanov apologised to the relatives of the victims for hiding the truth from them, and said he’d tried his best, but at the time, there was an “overwhelming force” in the country.

After Ivanov’s death, Oleg got access to the investigator’s personal archive and discovered some curious details about the autopsies, including the fact that some of the students’ clothing had traces of radiation. The makeshift morgue set up in the town of Ivdel, where the first four bodies were examined, was surrounded by security officers from the KGB, rather than the police, and nobody was allowed in.

Oleg mentions one more anomaly – a big barrel of alcohol was delivered before the autopsies, which he believes investigators used as a primitive form of protection against radiation.

“Small containers of alcohol were sometimes used to store fragments of organs,” says Oleg. “But this was a very large quantity and the forensics team were given clear instructions to wipe themselves all over with the alcohol, to rub it all over their naked bodies. Such measures never normally took place in those days.”

But if the military was testing new weapons and there was a radiation leak, why did it only affect these nine students and why wasn’t the whole area contaminated?

Oleg points out that it is a huge area, geographically, and few would have been aware of fallout in such a remote wilderness. Secondly, at the time of the students’ deaths, many animals and birds were found dead – and local people were suddenly banned from using water from wells. They had to bring in water from elsewhere.

Valery, the Mansi forest warden, told me that reindeer herders were banned from the area and hunting was not allowed for four years after the incident.

Something else makes Oleg suspicious. In the autopsy reports it says that fragments of the internal organs of the first five bodies were sent for chemical analysis. He unearthed a signed document stating the organs had been successfully delivered and were stored in a fridge. But as soon as the results were known, some people came to the laboratory and took the samples away, along with the paperwork.

“I don’t exclude the possibility that the problem fell from the sky,” says Oleg. “Meaning, there was an explosion. It’s impossible to say whether it was a military rocket. But why did the young people leave their tent in such a hurry and cut their way out? Because they couldn’t breathe, perhaps?”

Maybe they were affected by poisonous rocket fuel.

There have also been conjectures about shock waves from a low-flying jet or a strange tornado-like wind which terrified the students and forced them to run semi-clad into the snow.

Others believe that the violent injuries they suffered were caused by the Russian Yeti, an ape-like creature that towers above the average human. The evidence for this is one blurry photo, taken by one of the students of what appears to be a supernaturally tall figure behind a tree.

In all, around 75 different theories have been put forward - including an alien abduction.

Perhaps in response to so much speculation, in February this year the Russian prosecutor general’s office announced the case was being reopened. I was intrigued. If the authorities really did have something to hide, they would presumably ignore the 60-year-old incident rather than open a new inquiry.

On the other hand, it seems that officials have already made up their minds about what happened.

Alexander Kurennoi, spokesman for the prosecutor general, has said only three possible causes would be investigated - all of them connected with extreme weather.

"Crime is out of the question," he told a press conference in February 2019. "There is not a single proof… it was either an avalanche, a falling slab of hard-packed snow or a hurricane."

Having visited the site on Mount Khlolat Syakhyl, it’s hard to picture an avalanche - the gradient is not particularly steep. Moreover, the students’ tent was visible at the time of its discovery - not covered by several layers of snow.

Tatyana, Igor Dyatlov’s sister, is sceptical of the line being taken by the prosecutor.

“You have seen for yourself what kind of avalanche could there be when their tent was almost intact? A hurricane? Well maybe, but it is possible to survive a hurricane,” she reasons.

“As for a snow slab which crushed their tent - that doesn’t explain the injuries they had. And if it was just an ordinary hike which went wrong because of extreme weather conditions, well, those happen all the time, so why did it worry the highest authorities in the country?

“I think it means something extraordinary happened.”

But does it? Perhaps the most obvious explanations have been overlooked. Some have attributed Lyuda’s missing tongue and eyes to wild animals – after all, her body lay undiscovered for nearly four months.

In Moscow, I met Natalia Varsegova of Russia’s biggest-selling newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda.

Together with her journalist husband Nikolai, she has been writing about the Dyatlov case for the past seven years - and she doesn’t accept either the extreme weather or the weapons-testing theory.

“If the young people had been killed by an experiment,” she argues, “there is no way the military would have allowed ordinary civilians, friends of the students, to join the search party on that mountain”.

“It’s very strange for me to imagine that someone killed them, and then scattered their bodies along the slope, because one of the soldiers would let it slip before he died to some of his relatives – someone would have said something in drunk company.

“We live in a country where nobody can keep any secrets,” she says.

Natalia lobbied successfully last year to get the body of Semyon Zolotaryov exhumed. He was the odd man out, the 38-year-old in the group who conspiracy theorists suspect of being an agent for the CIA or the KGB – take your pick.

Now she wants more bodies dug up.

“After examining the injuries of at least the bones of the skeletons,” she says, “it would be possible to understand whether it was an avalanche, whether they were crushed by a slab of snow or it was, after all, people who killed them there.”

So could they have been murdered?

That is the latest theory doing the rounds on Russian television. In July, a programme called Na Samom Dele, which means In Truth, ran an hour-long special.

Eduard Tumanov, a forensic pathologist, told a shocked studio audience that one of the students was tied to a tree and tortured before his death.

Tatyana Perminova, Igor Dyatlov’s sister, finds all this speculation hard to take. She and the other family members would prefer their loved ones to rest in peace.

“Emotionally speaking this is very hard,” she says.

“Just imagine… digging up their coffins. But if there is no other way to find the answers - OK. Let’s see what happens next.”

The new inquiry is likely to report its findings in 2020.

“So many years have passed and still nothing is clear. And people are still interested,” muses Tatyana .

Legacy

When we visited the Dyatlov Pass, I imagined we would be the only people for miles around but about half an hour after we arrived, to my astonishment, a group of nine snowmobiles sputtered into view. They were tourists from the neighbouring Perm region on a weekend excursion.

We stood together at the base of the granite memorial - one boy pulled a couple of red carnations out of his rucksack and laid them underneath.

The memorial lists the students' names, the date they died and underneath that it says:

“In the memory of those who have gone and will never return, we have named this mountain pass in their honour – the Dyatlov Pass.”

As the wind howled around us, I thought about how young these people were and how little they suspected, when they pitched their tent on this slope, that it would be the last night of their lives.

“Apart from anything else,” says the father of the boy with the flowers, “this was a human tragedy and these students were true comrades. It seems as if they all fought desperately to stay alive but also tried to stick together until the end.”

As Tatyana says, the mystery surrounding her brother and his friends’ deaths has intrigued people in many different countries. There are books in several languages, feature films, documentaries and even a Polish video game.

We look at this case with a modern eye, in an era where our every step is captured on a phone and geolocator. We are used to instant communication almost wherever we are. We expect instant access to evidence stored on computers. Today forensic science has taken giant strides compared with 1959, and yet we also live in an era where our imaginations run wild on the internet.

Many of the most outlandish versions of events come from conspiracy theorists who have never set a foot in Russia. There is a Facebook group which I joined, and I am still amazed by the number of weekly, even daily, status updates generated by a story which is already 60 years old.

Newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda has long pushed the government to reopen the case, but whatever the findings are, they are unlikely to satisfy everyone.

I lived in Russia in the early 90s and I am still a frequent visitor, so it doesn’t surprise me that most refuse to believe the official version of events. Governments are distrusted everywhere yet in Russia the suspicion is especially deep rooted.

One of the TV hits of the year, Chernobyl, was a grim reminder of how far the Soviet authorities went to hide the truth.

And some things don’t change. Just this summer, five nuclear engineers died during a weapons test in the far northern Arkhangelsk region.

Initially, the Russian ministry of defence put out a bland statement about an explosion of a liquid-fuelled rocket engine. It also stated that background radiation remained at normal levels. However, local authorities in the city of Severodvinsk, some 40km (25 miles) away from where the explosion took place, saw a spike in radiation levels 200-times greater than usually recorded.

Three victims arrived naked in the local hospital’s emergency room wrapped in transparent plastic bags, but the medics who treated them were ill-informed about the disaster, had no protection and now fear they were exposed to radiation themselves.

Many decried a Chernobyl-style cover-up but for others, especially people in the Urals region, it was reminiscent of what happened to Igor Dyatlov and his friends six decades earlier.

Conspiracies help unite powerless people against an imagined “other”. While the West is currently reeling over accusations of election meddling, the Dyatlov mystery is a reminder that rumours of subversion of the truth by hidden forces are nothing new for the Russian people.

Credits

Author: Lucy Ash

Field producer: Richard Fenton-Smith

Researcher: Tatyana Movshevich

Graphics: Mark Bryson

Online producer: James Percy

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Photographs: Yuri Kuntsevich, Dyatlov Memorial Foundation, Getty Images

Thanks: Oleg Archipov, author and Natalia Varsegova, Komsomolskaya Pravda

Published: December 2019

More long reads

Tales from the far-flung Faroes

I love animals but I kill them too