Why dad killed mum

My family's secret

Tasnim Lowe's mum was groomed and then killed by her dad. Now Tasnim wants to know more about what happened to her mum, who she thinks of simply as Lucy.

It was difficult growing up. I lived with my grandad, and at primary school, people would ask questions. “Why do you live with him? Where’s your family? What happened?”

I didn’t know what to say. It’s not like I could go, “Hey, I’m Tas, my dad’s a murderer. Wanna be friends?”

I was 16 months old when my dad, Azhar Ali Mehmood, killed my mum – but saved my life. He wrapped me in a blanket, carried me out of the house and put me under an apple tree in the garden, away from the house fire that killed my mum Lucy, her unborn baby, my grandma Linda Lowe and my aunt Sarah. It was like he wanted to look after me – but he didn’t really look after me when he let my mum die.

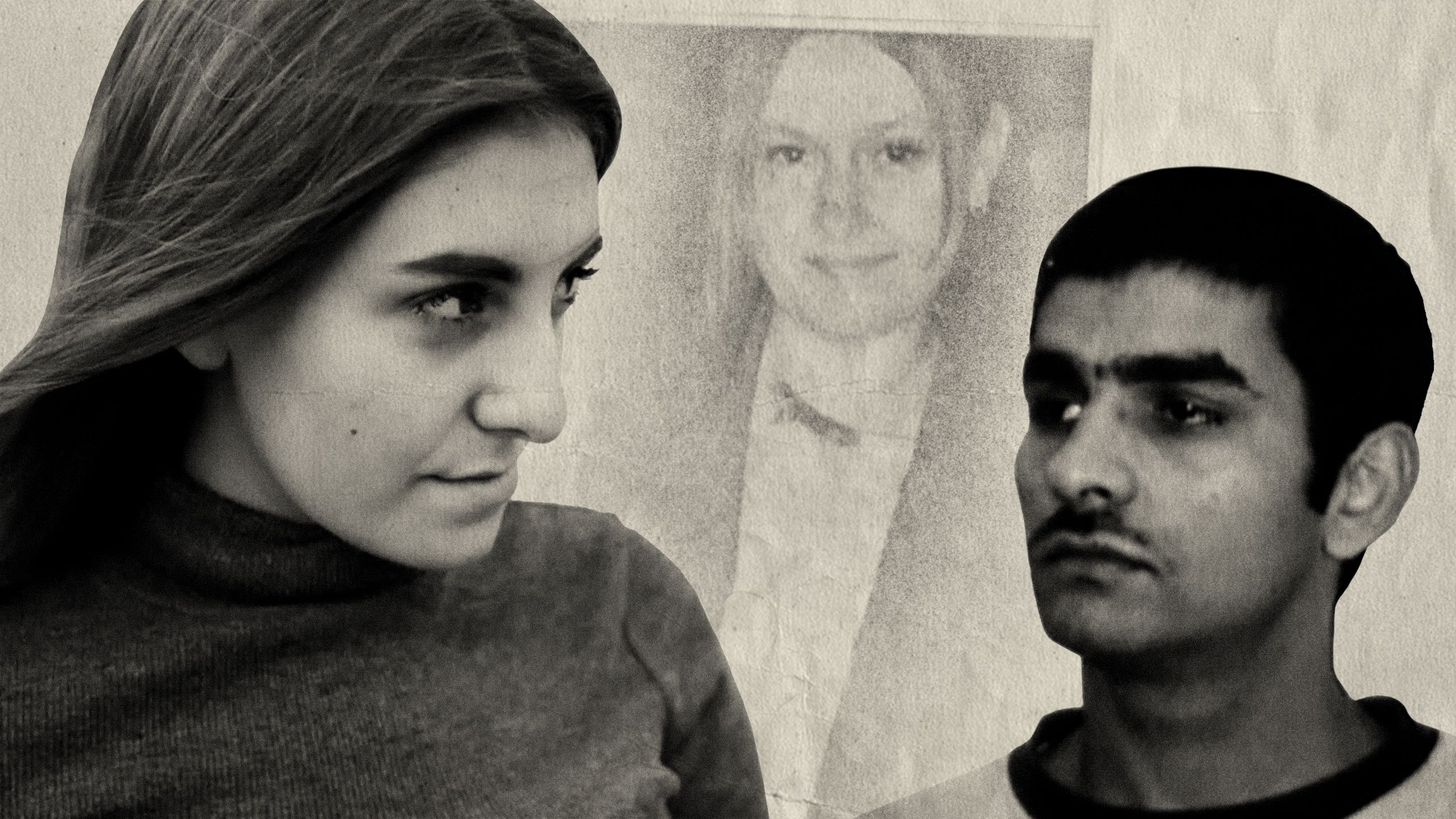

Tasnim holds a framed photo of her mum, one of the few that survived the fire

Tasnim holds a framed photo of her mum, one of the few that survived the fire

It was my dad who started the fire at our house in Telford in Shropshire in August 2000. The following year he was convicted of the triple murder. Growing up, my parents didn’t seem like people to me – they were just a story. So, in 2018, when I got the opportunity to make a documentary with BBC Three about my background, I took the chance. I wanted to delve deeper into why the arson attack happened, and find out more about my mum, and myself as well.

I feel like I look like the brown version of Lucy, but when I think about her, I think of a teenager. I don’t really see her as a mum, so I don’t want to call her mum. She was 15 when I was born, and my dad was 25, but it didn’t cross my mind when I was younger that Lucy and my dad’s relationship wasn’t right. If I talked about them to people at school, they’d always look at me funnily and say, “That’s a bit weird, isn’t it?”

I’d say, “No, it’s fine, they were in a relationship!” I was programmed to think that way, because that’s what I was taught by my family, and I didn’t understand at first why people were saying things about it. Me and my grandad George are really close, but it’s been difficult. He lost his wife Linda and two daughters in the fire. And he brought me up afterwards – he vowed after my dad’s trial to look after me. But we have two completely different opinions and mindsets on the subject of my parents’ relationship.

Tasnim and her grandad George at a memorial service for her mum, aunt and grandma

Tasnim and her grandad George at a memorial service for her mum, aunt and grandma

Back then, he – and some others – had a different view of age-gap relationships. It’s very difficult for me to understand how people could view it as OK that Lucy was a child when she was pregnant with me, but through the process of making the documentary, he’s been more educated about the situation. He’ll now ask me about what things are right and wrong. It’s been challenging, but I think we finally have come to some kind of agreement on things.

I met some of Lucy’s friends while making the documentary. Lucy was a child when she met my dad, and her friends were a similar age. It’s only in hindsight now that people can see the relationship was wrong. One of her friends told me that at the time, it was fine, it was seen as cool to see older guys. If they couldn’t see what was happening, maybe Lucy couldn’t, either.

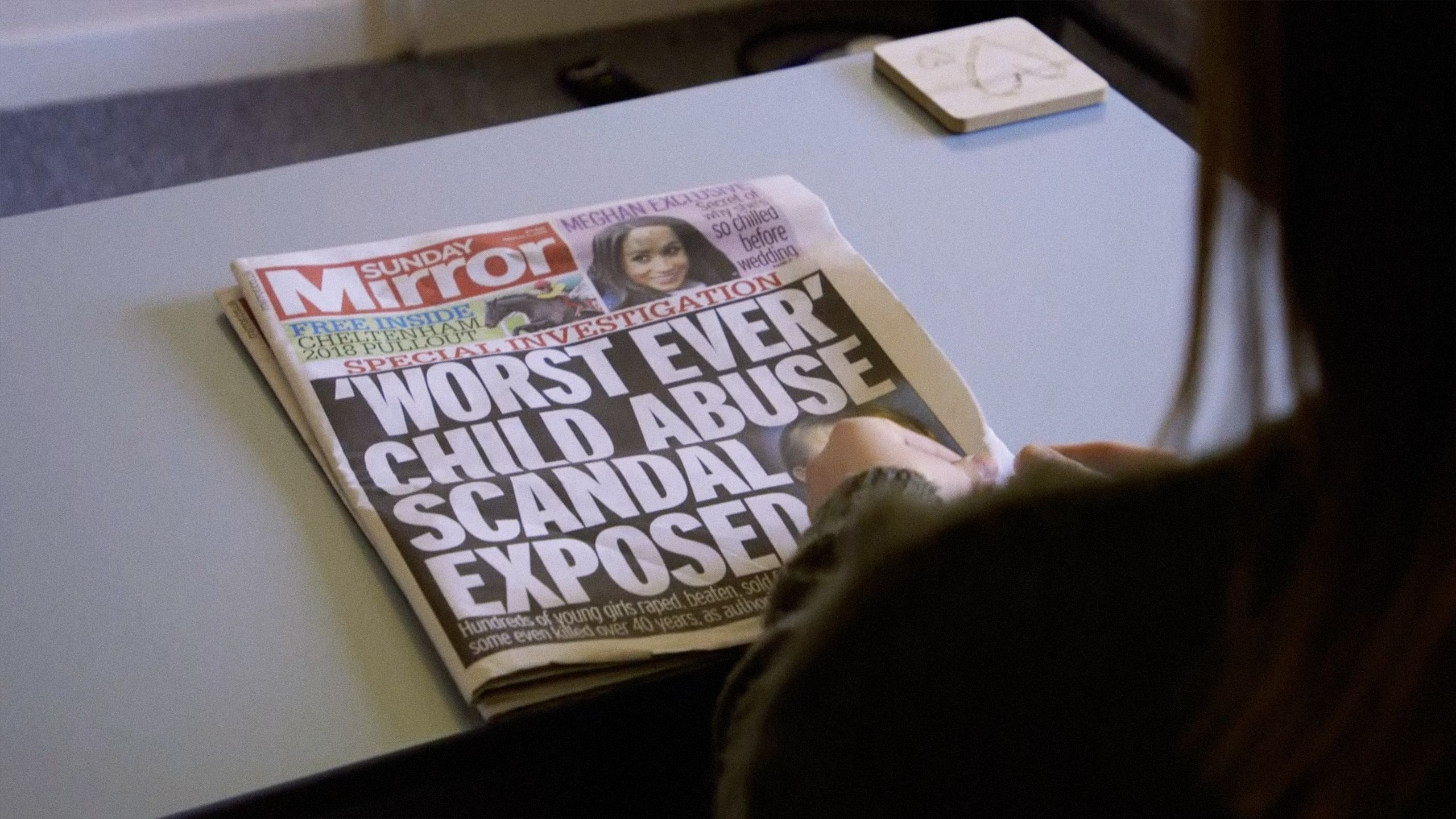

A story about Tasnim's parents in a local newspaper

A story about Tasnim's parents in a local newspaper

It was Sunday 11 March 2018 – Mother’s Day – that something happened that challenged everything I’d been told about my parents. On the front page of the Sunday Mirror was a picture of Lucy. At first, me and my family were all really confused by it – when I saw the article, I assumed it was an old story about the fire that had been republished for some reason. I remember thinking to myself, “There can’t be any new information”.

We as a family – and as a society in the UK – hadn’t realised at the time there was so much more to the story. It’s bizarre, looking back now, how obvious it was.

The Sunday Mirror’s investigation revealed that up to 1,000 children could have been groomed in Telford since the 1980s. It described how my dad groomed Lucy from the age of 14, and that other girls being abused were threatened with “ending up like Lucy” – in other words, dead – if they told anyone.

I was so confused at first. When you’re taught a certain story, you know that story, you understand that story, and think that’s the only story it could possibly be. That’s how I felt about my parents before seeing the article – it was OK, because they were in a relationship. Seeing a different story in the paper, at first I thought, “No, that didn’t happen. They’ve got this wrong.” It was really difficult to accept this completely new perspective, and it was so personal. It took a while to come to terms with it.

The investigation made me question everything I thought I knew about my past, and I had to find out more. I decided to look at the court transcripts from my dad’s trial to see if they held any more clues.

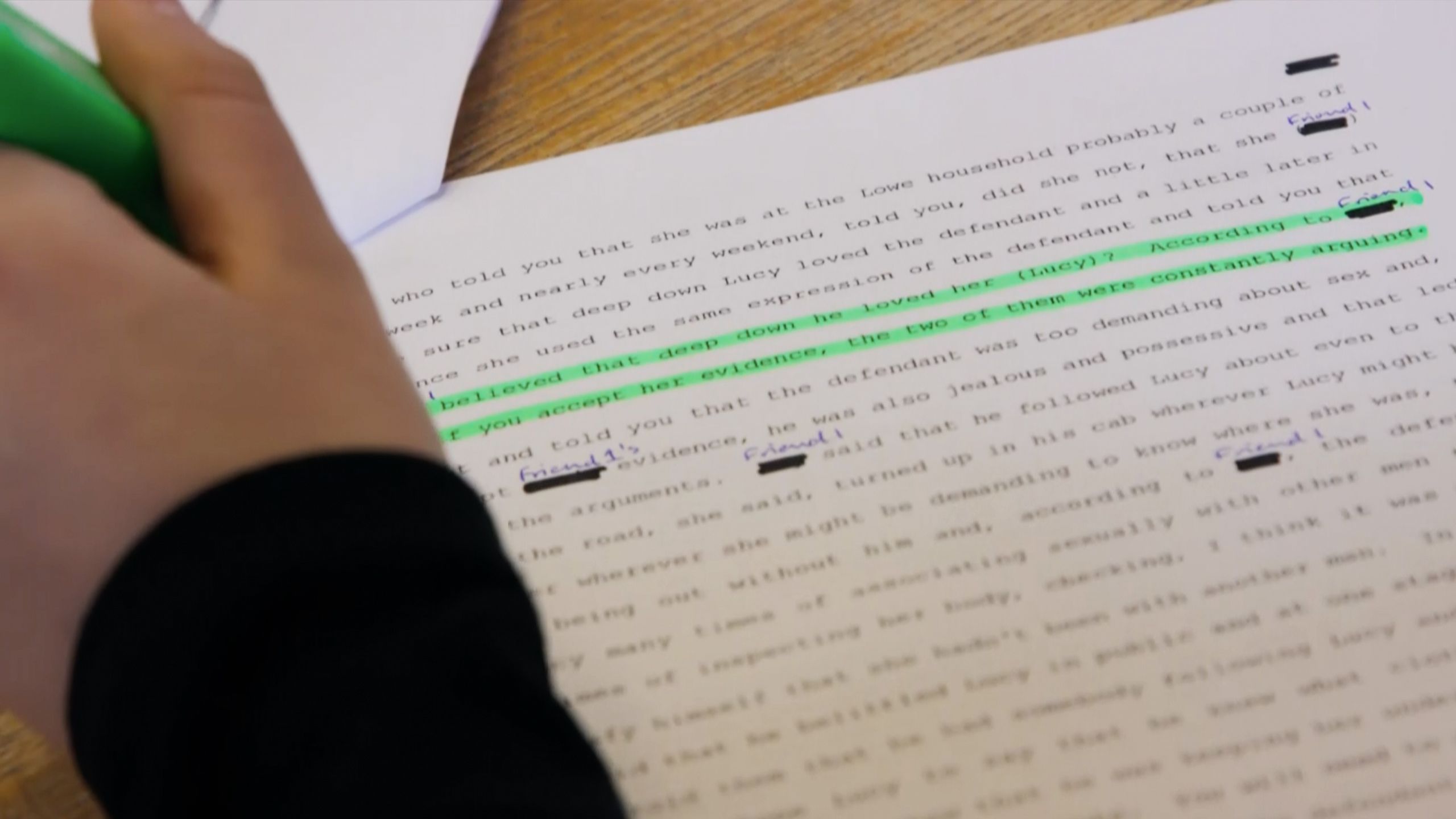

Tasnim returns to the original court documents to search for clues

Tasnim returns to the original court documents to search for clues

It was very confusing reading the records of the hearing. Lucy and my dad’s age gap was mentioned, but people didn’t seem to acknowledge it. It wasn’t just two or three years – it was nearly ten years. According to my mum’s friends, my dad would check her, examine her body, to see if she’d been with other men. He’d ring her to say he had someone following her to keep tabs on her. There were suspicions she was having sex with other men in the churchyard. We don’t know if it was a gang thing, if she was being exploited, because it wasn’t looked into.

Lucy Lowe was 14 when she became pregnant by taxi driver Azhar Ali Mehmood

Lucy Lowe was 14 when she became pregnant by taxi driver Azhar Ali Mehmood

Me and my grandad have spoken about it a few times. I've always challenged him – why didn’t he do anything? Why did he think the relationship was OK?

Grandad told me he “didn’t take much interest” in my dad – but that Lucy and my dad argued a lot. I asked if that was because my dad was demanding sex from her.

“He did go upstairs a lot,” my grandad told me. “One time, I heard someone shouting, ‘Rape! Rape!’ I went running in, I kicked the door down, and he went running down the stairs and outside. The neighbour’s boyfriend ran after him.”

I asked why nobody told the police.

“I don’t know. Was she crying out for help? If she came to us, we would have done something.”

“But you and Linda heard her shout ‘rape’ and you did nothing,” I responded. “That was abuse, it makes me sad.”

It also upsets me, though, that there’s all this blame, all these questions as to who’s at fault. I had to ask these questions, because I wanted to understand. I think my grandad does feel a lot of regret, a lot of hurt that there were things he and my grandma Linda could have acted on. But back then in society, everybody felt the same. Nobody had any education on the matter. Even if my grandparents did do something, would the professionals have listened to them?

I wanted to know how my dad felt, too. Was he sorry? What did he think about the arson attack now? When I was 16, I went to visit him in prison. It wasn’t a hard decision. I’d have gone sooner if I could, but there was a court order that stopped me until I was 16. Initially, I just wanted to meet him, have a catch-up, and understand the situation. I also wanted to meet him and understand his hobbies, his dislikes, him as a person, and find out a bit more about where I’m from. I wanted to form my opinions based on him as a person, not just what happened.

The way I feel about him is confusing. It’s not black and white. The answers he gave me – it was like I wasn’t getting a full response, almost like I had to record what he said and listen back to it a few times, to read between the lines. Certain things he’d open up about, and others he wouldn’t – it depended on what I was asking him. But I’m glad I went. I needed to do it. I think there was more that I’d have liked him to tell me that he just wouldn’t give away.

I think it’s a failure of the justice system that my dad wasn’t prosecuted for the sex crimes against my mum as well as the murders. I think people should be charged with each individual crime. We did look into it, and I asked the police why it didn’t happen at the time, but the police officers working now aren’t the same ones that dealt with the case at the time, so there was lots they couldn’t tell us. I’ve got to be honest, I didn’t find them that helpful when I asked for details about what happened at the time, but I presume it would have been a breach of confidentiality for them to tell me. I am really grateful, though, that we were able to get some of Lucy’s belongings. I got her diaries – at the moment of her writing them, nobody would have seen them. It’s made me feel closer to her as a person and it’s definitely made me more aware of the things that my dad was involved in back then.

Tasnim holds her mum's school diary which, until recently, had been held as evidence by police

Tasnim holds her mum's school diary which, until recently, had been held as evidence by police

My dad’s now eligible for parole. Ultimately, you can’t just add on other crimes to keep someone in prison. I get it. I think that’s a failing of the system and society back in the day, that he’s never faced justice for abusing my mum.

It has been very sad and hard at times, but there are a lot of positive things to come out of making this documentary. I became closer to Lucy, and understood more of my background and identity. I got closer to my grandad, too. It’s given me a better understanding of child sexual exploitation (CSE) as well, and I’m glad I could make people more aware.

For now, I just want to have a break, and look after myself and my own mental health. But in the future I would like to get involved with other things to do with raising awareness around CSE. I’m in such a fortunate position of someone who hasn’t been through this personally, but what happened to my mum has given me this understanding.

I can be a voice for Lucy that she never had.

West Mercia Police declined to comment.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can find advice here.

BBC Three documentary Why Dad Killed Mum: My Family’s Secret is available on iPlayer on 13 November from 10am.

Credits

Tasnim was speaking to BBC reporter Thea de Gallier

Editor: Stuart Duggan

Design: David Weller

Additional photography: The Lowe Family