The Lancashire

hideaway of an

Italian mafia boss

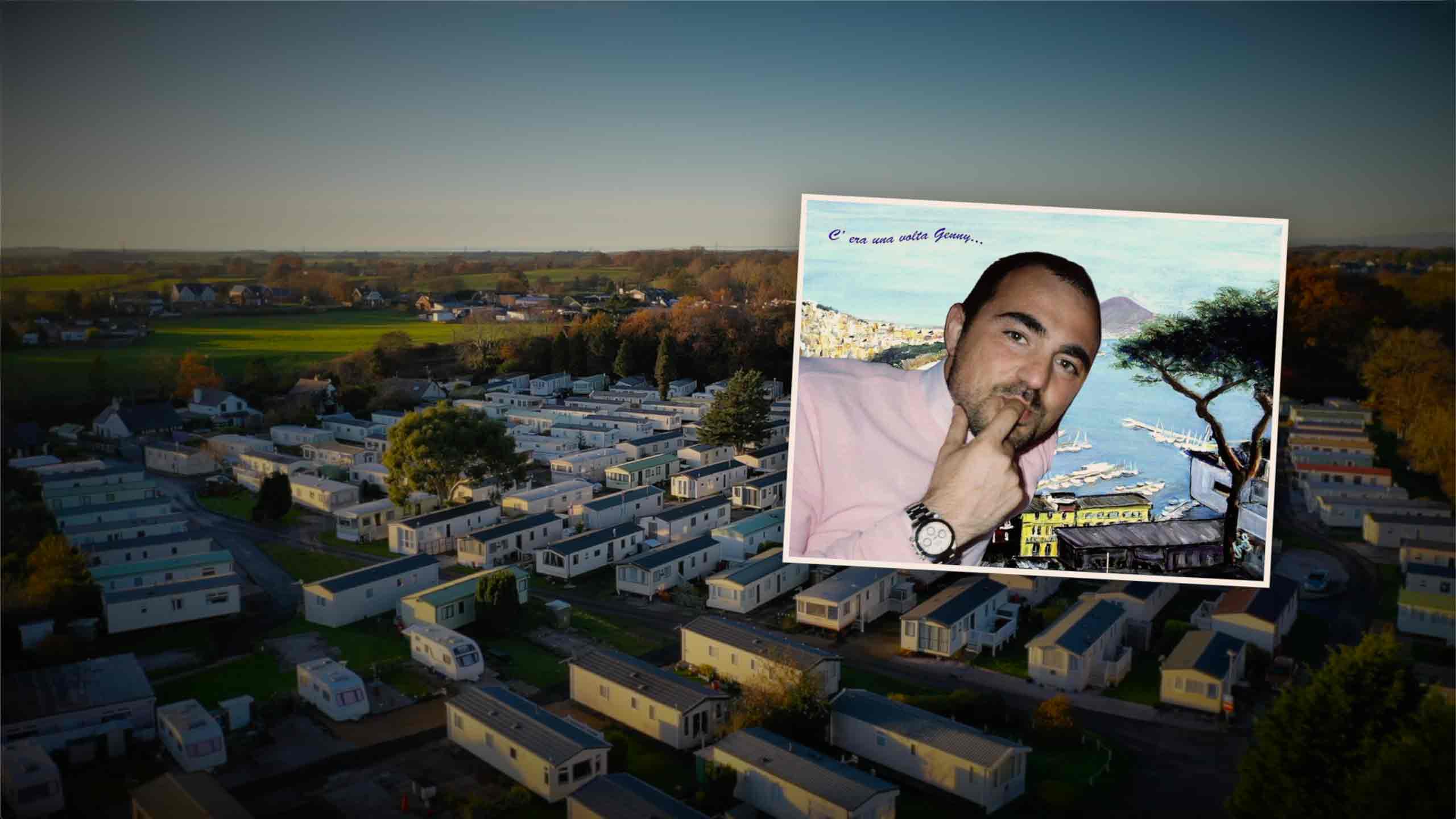

In a cupboard, in a caravan park in northern England, there is a pair of Italian leather dancing shoes. Every now and then they are brought out and polished up, before their owner spins across Northern Soul dance floors. Those shoes are treasured by their owner, a hard-working man called Mick.

The man who gave them to him was his new Italian neighbour.

His name was Gennaro Panzuto.

People liked the gregarious charismatic Italian guy trying to grow pots of basil in the wind-swept chill of rural Lancashire.

And Gennaro liked the caravan park because it was a good place to live quietly. It was a good place to hide from the truth written in blood on the streets of Naples.

But that truth was soon to catch up with him.

The interview

It is June 2019, about 12 years on from when he gave those shoes to Mick, and I’m waiting inside a maximum security prison.

I’m almost as far north in the Italian Alps as I can get before they start serving French cheese.

It’s claustrophobic inside the bleached hot walls of the dilapidated jail. The only view is of the sky and - if you can find a decent window - the stunning mountain peaks.

Prison near Aosta, northern Italy

A jailor unlocks an internal gate, and Gennaro Panzuto walks towards me.

The 45-year-old is fit and lightly-built. He’s not in a prison uniform, but a pair of snug jeans and a designer denim shirt and trainers.

We exchange pleasantries. And then we’re down to business: the confessions of a mafia man. He’s got an important story to tell about his life - and questions to answer about what on earth he was doing in the UK all those years ago.

We know it is a story that starts with appalling crimes in Naples, and ends with a mafia summit in the middle of Lancashire. But will he be honest and straight?

What crimes have you committed, I ask?

Gennaro Panzuto talks to Dominic Casciani

“My crimes range from murder, attempted murder and mafia association, extortion, drug trafficking, arms trafficking and money laundering.”

How many murders were you involved in? How many did you personally commit?

This is, after all, supposedly a confession. Panzuto hesitates.

More than 10?

“No, less.”

More than five?

“No, wait…”

Panzuto says he wants to be frank - but his frankness is tempered by an apparent reluctance to incriminate himself beyond what he has already been convicted for.

He insists that his time in prison has given him time to think - and he wants to tell his story as a warning to others not to follow his path.

Street kid

Gennaro Panzuto was born in the chaotic city of Naples in 1974.

His family’s tiny apartment was in La Torretta, an enclave of dirt-poor families amid the rich elite near the waterfront.

It was in an area known as the “Bassi”, or “The Lows”, a maze of dark, damp alleys at the lowest levels of the city’s ancient streets.

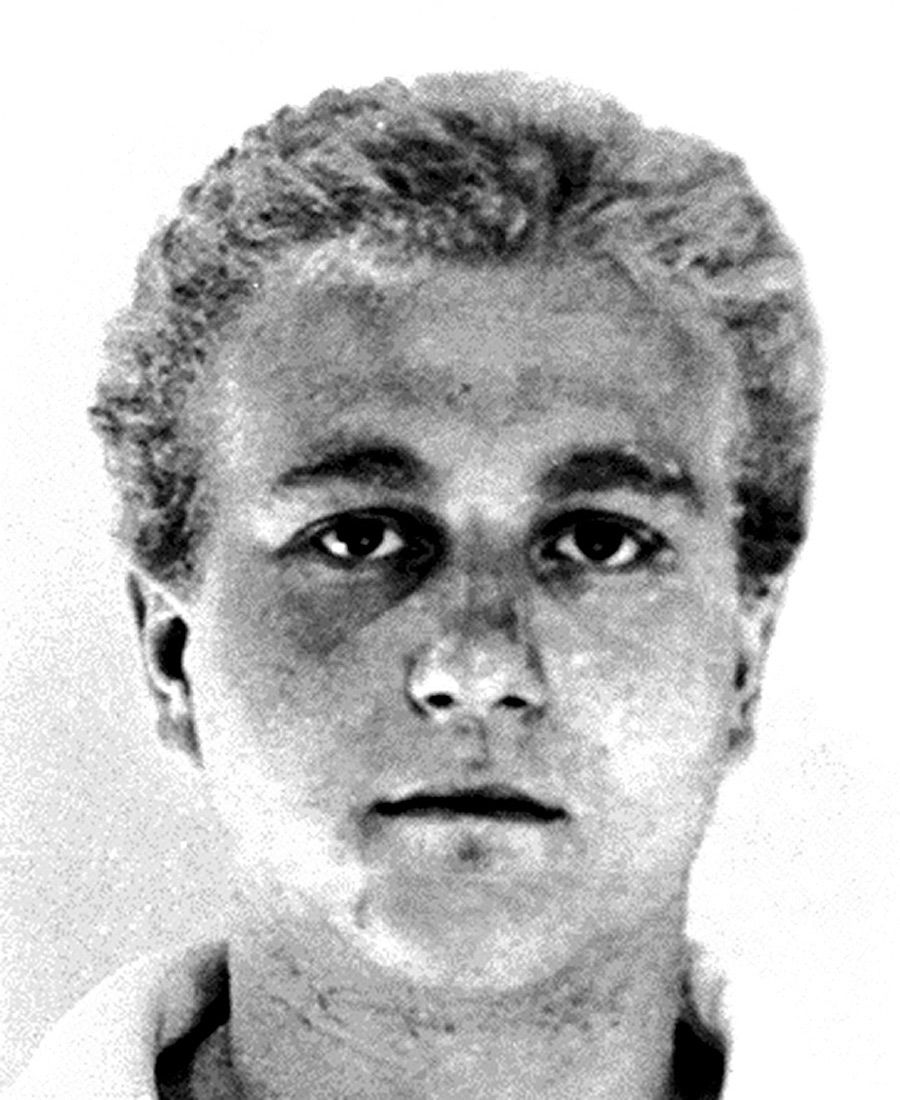

Gennaro Panzuto as a young man

If you lived in the Bassi, you were looked down upon, metaphorically and literally, by those above you wealthy enough to inhabit the sun-kissed rooftops.

He wanted to escape the poverty. And like so many other teenage boys there, his route out would be crime.

By the time he was 14, he had discovered he was an efficient thief. He had the guile and brass neck to steal watches - particularly Rolexes - straight off the wrists of the unsuspecting rich.

“It’s all about being cunning and sharp,” he recalls, showing me how he would steal a watch as he leapt from a moped.

Panzuto was so good at it, the people he was selling them on to asked him to move to Spain, where there were richer pickings. From Monday to Friday he would be stealing watches. Then on Saturday he would bring home his haul, and party.

“I was really renowned. That was my bad luck.” It was his bad luck because he had been talent-spotted by the Camorra - Naples’ mafia clans.

Gennaro Panzuto was born in the chaotic seafront city of Naples in 1974.

His family’s tiny apartment was in La Torretta, an enclave of dirt-poor families amid the rich elite near the waterfront.

It was in an area known as the “Bassi”, or “The Lows”, a maze of dark, damp alleys at the lowest levels of the city’s ancient streets.

If you lived in the Bassi, you were looked down upon, metaphorically and literally, by those above you wealthy enough to inhabit the sun-kissed rooftops.

He wanted to escape the poverty. And like so many other teenage boys there, his route out would be crime.

By the time he was 14, he had discovered he was an efficient thief. He had the guile and brass neck to steal watches - particularly Rolexes - straight off the wrists of the unsuspecting rich.

Gennaro Panzuto as a young man

“It’s all about being cunning and sharp,” he recalls, showing me how he would steal a watch as he leapt from a moped.

Panzuto was so good at it, the people he was selling them on to asked him to move to Spain, where there were richer pickings. From Monday to Friday he would be stealing watches. Then on Saturday he would bring home his haul, and party.

“I was really renowned. That was my bad luck.” It was his bad luck because he had been talent-spotted by the Camorra - Naples’ mafia clans.

The family

The Camorra are completely different to the Hollywood stereotype of a single all-powerful family controlling an entire city or country.

Dr Felia Allum, of the University of Bath, has spent her career researching the clans - and their unique criminal alliances across Naples.

“In every district you would find a criminal family that controlled the territory,” she says. But a family alone was weak. And so across Naples there are wider, shifting alliances.

Felia Allum

“What those alliances tended to do, in order to be powerful and strong, was to recruit smaller clans.

“That’s the flexibility and the fluidity of the Camorra.”

Panzuto’s introduction to the Camorra came via an aunt who had married into the mob.

Her husband, Rosario Piccirillo, headed one of the clans in his impoverished district and managed tax-free cigarette smuggling which made huge profits for his particular alliance in the city.

But Rosario wasn’t a brilliant leader, and had few foot soldiers to do his bidding. He realised he needed to train an apprentice whom he could trust with his life, to help the clan survive.

Rosario Piccirillo

Panzuto was called home from Spain for what would become a life-changing meeting.

He met his Uncle Rosario at Mergellina Marina - a playground of the rich on the edge of the clan’s territory.

There, Panzuto was introduced to a senior Camorra fixer - a man who solved problems for the alliance. This man had a proposal for the street thief. Rivals were planning to shoot Rosario in a growing tit-for-tat battle for control of that part of the city.

“Kill the person who wants to kill him,” Panzuto was told. “You have to do it because you’re his family.” Panzuto agreed to become a killer.

As he told me about his decision, he did so in such a matter-of-fact way that it didn’t make any sense to me.

Didn’t he think it was wrong? He was being asked to become a murderer - and he didn’t stop to say no?

“When you grow up in the world into which I was born, this [decision] was normal. I grew up with rules which meant that when I was bound to someone, I was also capable of murder.”

Panzuto kept to his promise to protect the family from enemies.

The first rival clansman he was told to target escaped with his life - but only because the police arrested him first.

But it wasn’t long before he ambushed another Camorrista and shot him dead. It was his job, he says, and he got on with it without thinking too much about the enormity of his crimes.

Today - after 12 years in prison - Panzuto insists he finally realises the horror of what he did. He’s been through several periods of psychotherapy designed to make violent offenders take responsibility for their actions.

He says he’s also put up walls inside his head to cope with his own inhumanity - but there are memories he can never escape.

“I don’t remember the faces,” he says. “I remember the dull thud of the bodies falling after you’ve shot them.

“I remember the screams of the children, the women, ringing in my ears.”

Over the next decade, Panzuto came to play a leading role in both extortion, and shipping drugs on his home turf, La Torretta.

And by 2005 Uncle Rosario was so up to his neck in police problems that the apprentice had to take over, to stop the clan collapsing.

Pietro Ioia is a former drug trafficker gone straight. He had met Panzuto during his rise. He says the young mobster was so assertive and quick to act that other crooks nicknamed him “Terremoto” - Earthquake.

“Panzuto was really respected by the other clans and had value as a boss. His Camorra career was intense - but short,” says Ioia.

Pietro Ioia

In the winter of 2005-06, a new inter-clan war erupted, and Panzuto’s allies asked for his help holding the La Sanita area.

Michele Del Prete is a senior anti-mafia prosecutor who investigated Panzuto. He says the young leader took advantage of the opportunity to make his mark.

“Panzuto needed to assert his own criminal character - his criminal weight,” he says: “As a killer, but also as someone who wanted to replace his uncle as a manager. He wanted to head a clan that could extend to other areas of the city.”

Over that winter, there was a spate of shootings and murders, as gangs tried to kill each other’s leaders and foot soldiers.

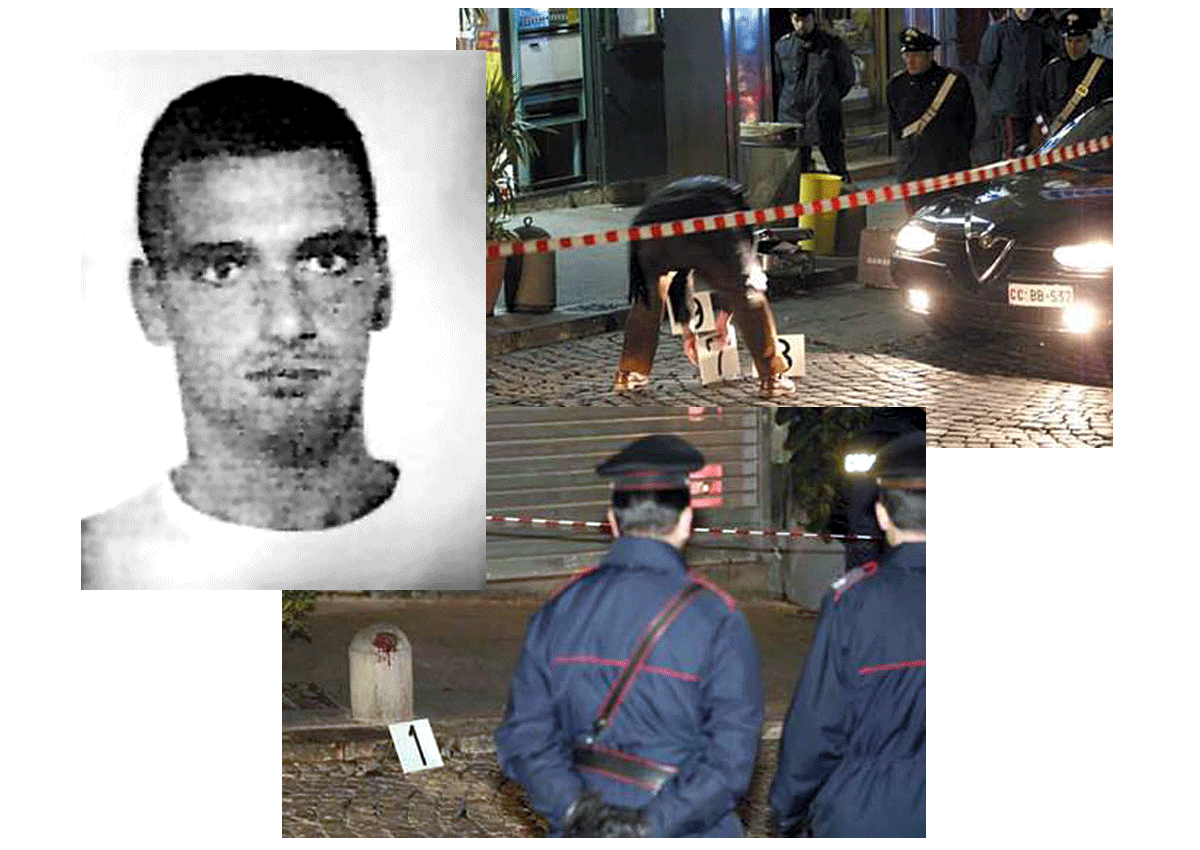

Eventually one of these murders - of a gangster named Graziano Borelli - could be linked directly to Panzuto.

Graziano Borelli (l) and a scene from a murder during the inter-clan war

The police had intercepted a conversation in which Panzuto had told his gunmen to carry out the murder, and they had enough evidence to launch a blitz of arrests.

But Panzuto was nowhere to be seen. He had fled the country.

Park life

The average temperature at the height of spring in Naples is 24C.

In Lancashire it’s 16C. And if there’s one thing that Italians moan about when they come to England - other than the food - it's the weather.

But Preston, in Lancashire, was where Panzuto fled to in the early months of 2006. So why this unlikely corner of England? Panzuto explained it to me during our prison meeting.

The Camorra has links around Europe, in order to do business. Some of its profits come from the illegal tax-free movement of goods in and out of Naples, and the clans do that with the help of overseas partners.

One of Panzuto’s closest associates in Naples had made deep connections to an organised crime gang in north-west England.

“These English guys were scrambling to meet me... then we went to the pub”

This gang - made up almost entirely of British men - was making a lot of money without needing to be violent on the streets.

One of their scams involved shipping shoes into Naples without paying any VAT - the Camorra would sell them on and undercut legitimate traders.

The British gang was headed by a businessman who appeared to be an entirely upstanding member of his community. He had a lawyer who was as bent as they come and an accountant who cooked the books in case the tax man came looking.

Panzuto had met the British businessman in Naples.

As the police closed in on him after the Borelli murder, Panzuto’s British friends offered him sanctuary in Lancashire. This presented him with two opportunities - a chance to hide out for a while, and also to learn about a lucrative business.

When he arrived at Liverpool John Lennon Airport, the British boss had a special welcome for his Camorra friend. A Rolls Royce was there to collect him.

“You don’t know how much I smiled,” Panzuto says. “These English guys - and they were scrambling to meet me - they sent me this chauffeur. And then we went to the pub.”

Once there, he met the wider circle around the businessman and was given important insights into their operations - all over a pint of bitter.

Panzuto told them his priority was to lie low, and the British businessman said he could sort that out right away.

Gennaro Panzuto in the UK

The Six Arches Caravan Park lies in a bend in the River Wyre, halfway between Preston and Lancaster.

Apart from the occasional high-speed train passing, it is a peaceful spot - a short drive from the Forest of Bowland, and the seaside delights of Blackpool and Morecambe.

Panzuto rented a unit at the caravan park, and his wife and children arrived from Naples.

He was a little vague about his background. But, being a chatty kind of guy, he quickly made friends.

Park staff remember their new guest had a thing for flash cars - and had to be ticked off for breaking the 5mph speed restrictions. The cars, including a Porsche, were gifts from his host.

It was a welcoming place, and neighbours happily lent the family a phone to call home. It didn’t occur to anyone at the time that this was a bit odd, given he clearly had money.

And one of the neighbours who helped the Panzutos settle in was Mick Bury.

Had Mick known at the time what he knows now, he may have thought twice about banging on Panzuto’s door after the Italian had driven into his car.

“I was that worked up about it, I said, ‘Oi! Have you seen what you have done to my car? Couldn’t you see it?’”

Mick Bury

Gennaro Panzuto, confronted with a furious Lancastrian yelling at 100mph, gesticulated apologetically. Then he gave Mick a piece of paper with a phone number on it. Mick phoned the number and a man with a local accent said he would be there in 20 minutes to sort it out.

The local man - arriving in a nice car and wearing a suit - listened to Mick’s complaint.

He looked at the damage and - there and then - peeled off £200 from a wodge of notes. He told Mick there would be another £200 the following week.

“No questions asked - he just wanted it sorted,” says Mick.

And then, Mick and Panzuto became friends. During that summer’s World Cup Finals in Germany, they shared a laugh and a beer, as they watched Italy win the tournament for the fourth time.

“The joke - when I went out with my friends - was, ‘Hey, you need to watch out, he might be a mafia man…’”

In time, their friendship became such that Panzuto gave Mick, a dedicated dancer, a gift of Italian dancing shoes.

They were made of the softest black leather, with a stripe of brown across the toe. The smooth sole was made to glide. “I still wear them now - I couldn’t afford them. He was very generous.”

Panzuto made other friends on the site. Russ, the maintenance manager, remembers the Neapolitan buying people drinks in the park’s social club.

He would turn up with sample shoes and leather coats - and then give them away. People loved the extravagant new resident.

And Panzuto was beginning to enjoy his life in England. There was, he told me in prison, a peace and quiet unlike Naples. But it wasn’t a holiday.

The British businessman boss who was helping to hide him, now needed the favour paid back in a way that only Panzuto could do.

The message

Panzuto’s host was owed a fortune by other crooks who were part of his extended network of dodgy companies and tax scams. The Italian wanted to learn more about these companies - and the British businessman said he’d teach him everything he knew.

But first, Panzuto was needed to turn the screw on his debtors. The businessman - who liked to clock off early and go to the pub to brag about his mafia mate - wanted an efficient solution.

And so Panzuto said he would deal with this problem the Camorra way. He set up a fake business dinner at an Italian restaurant in the Preston area with a foreign businessman who was causing the most upset.

The target was refusing to pay his debt to Panzuto’s British host.

“He was the cockiest of them all,” said Panzuto. “He not only owned him money - he was threatening, too.

“I took him to the car park. He thought that we were going to take the car. Instead… I grabbed him and head-butted him. I threw him to the ground.”

The victim was stunned by this sudden attack.

“I said to him, ‘Remember what I’ve done. Tell everyone this is how the wind blows now.’"

And then he committed an act of extraordinary violence. He bit off the victim’s ear - and Panzuto says the British boss saw it happen. The message had been sent by a Camorra man. And the debtors started paying up.

Now it was time for him to learn what he could from the British.

Within months of coming to the UK, Panzuto was shown by the British businessman how easy it was to open bogus companies - unlike in Italy.

That made white-collar crime - hiding criminal profits in apparently honest transactions - very easy.

Unlike the Camorra, the British boss didn’t need to sell drugs, or extort money from local businesses.

He simply shifted goods around company after company, while dodging the 20% VAT that other traders had to legitimately cough up.

Panzuto tells me he never understood entirely what was going on, but it amounted to carousel fraud - a crime that costs governments billions every year.

The scam usually involves sending goods across EU borders - in this case to and from Italy. The VAT that is owed is never recovered, as the companies are wound up and the goods disappear.

And it’s the type of fraud which Italian investigators have long been most concerned about.

Panzuto had foot soldiers to support back in Naples - including welfare payments to the families of jailed associates.

These white-collar scams were proving lucrative - and the British businessman boss said he could help move more shoes, bathroom parts and cars, to cover Panzuto’s outgoings.

Panzuto said the plan would help his people - and he knew it would help his own position on the Camorra’s greasy pole. He began investigating setting up a network of front shops and warehouses in nearby Preston - and possibly Manchester - to generate even more cash to send to Naples.

But the ambitious young boss, lulled into a false sense of security by the arrogance of his British associates, was already making mistakes.

Back in Naples, Panzuto was a prime suspect for the city’s mafia-hunting Flying Squad. Then, Inside the elite police unit’s smoke-filled, nicotine-scoured offices, detectives got a breakthrough - thanks to five repeated numbers.

00-44-7.

The international prefix for UK mobile phone numbers.

As the Italian state directed its surveillance tools at a wanted killer, his associates and family in Naples appeared to be connecting to British mobile numbers - 12 different numbers in total. One of them may have been Mick Bury’s handset at the caravan park - given that Panzuto’s wife had been borrowing it to call home.

“It was definitely a surprise for us. It was a novelty to consider the UK,” says prosecutor Michele Del Prete, who was far more used to finding men hiding in the warmer climes of Spain.

The detectives needed to know for sure whether Panzuto was in England. They asked Scotland Yard and the Serious Organised Crime Agency to help.

And that was when their quarry may have made two massive errors.

Panzuto's address in Garstang, Lancashire

By 2007, Panzuto had moved from the caravan park to a semi-detached house on Cock Robin Lane, Garstang - a lovely quiet village north of Preston.

His first mistake was to fly his wife in regularly, and then his girlfriend, when his wife left.

He now believes that their movements gave away his location.

Secondly, his closest lieutenants were flying in every few weeks to discuss business. All of these movements gave the Italian police leads to follow.

Panzuto was now in executive control of operations from far away, ensuring the dirty work got done, without getting his own hands dirty.

Such was his power - even from England - that he once ordered a rival to be burned out of his home in Naples.

His soldiers delegated the job to a drug addict, who set fire to the wrong apartment.

“I was angry,” Panzuto later admitted in an interview with prosecutors. “I told [my lieutenants] to beat him for the mistake.” The underlings then duly went back to burn out the correct target.

To reinforce his growing power, Panzuto was bold enough to invite all of his allies to a mafia summit at Cock Robin Lane. About a dozen leaders from across his alliance made the trip - including bosses from three of the biggest Naples clans.

He disguised the meeting as a family BBQ. There were two items on the agenda as the meat sizzled on the grill.

Item one - more hits against the enemy. The 2005-2006 war that led Panzuto to flee had been painful - and members of the alliance wanted a final push to eliminate all threats.

But Panzuto wanted to focus on item two - easy cash.

“I made them understand that this war had led to a bunch of arrests - now was the moment to pause, and reflect on economic plans,” recalls Panzuto.

He had a long list of plans - including an ambitious attempt to profit from the refurbishment of the marina in Naples, where he had been recruited 10 years previously.

By now he was also in negotiations with his English helpers about how to leverage their financial muscle into his own world. The plan involved setting up a front business in England, posing as a network of shoe stores, to help shift cash back to Naples.

But it never got off the ground.

On 16 May 2007, the knock on the door came.

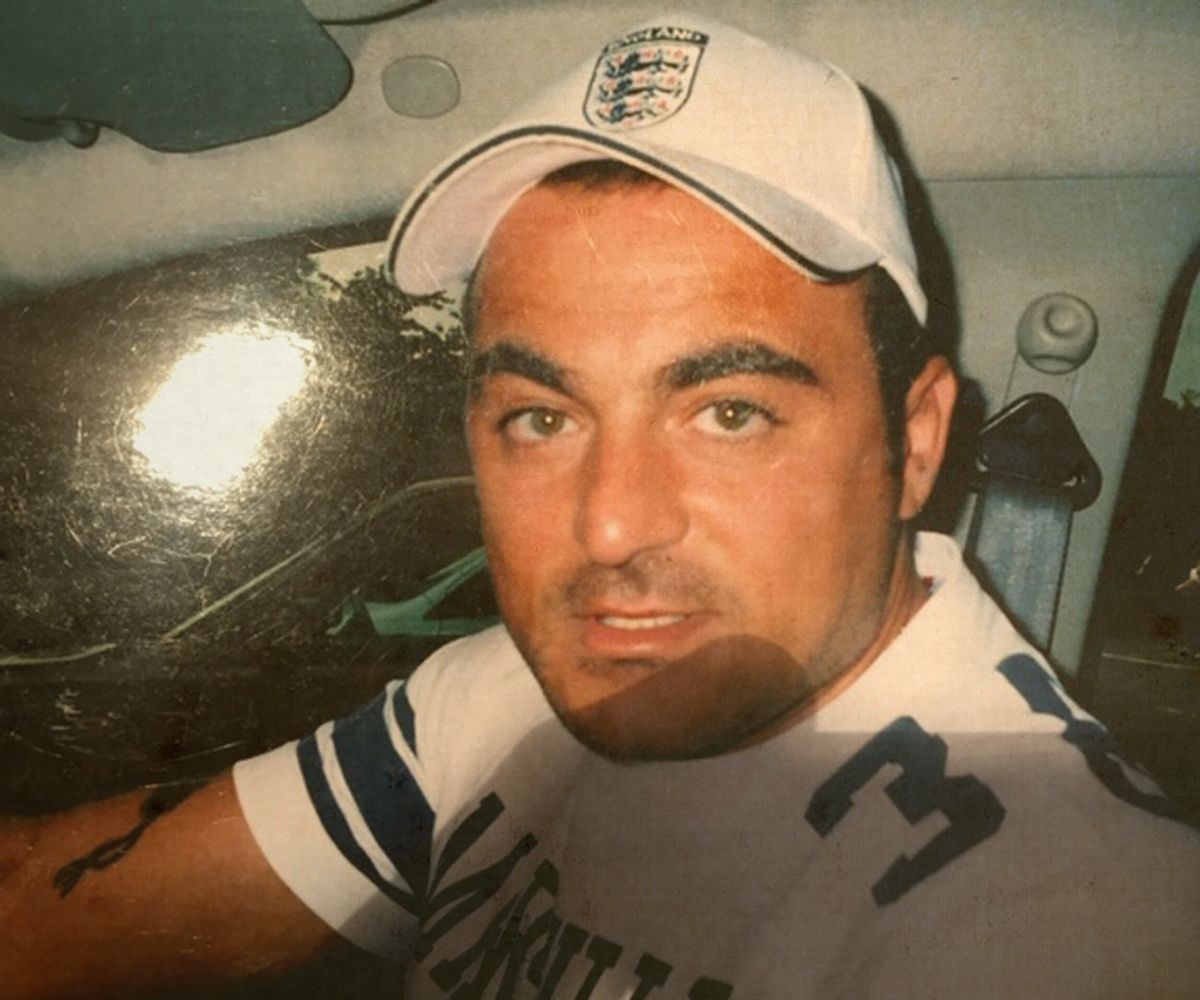

Police mugshot of Gennaro Panzuto

“I remember that day like it was yesterday. I went to look out and there were men in plain clothes - at the front and at the back. And then I knew.”

The polite British officers asked if there were any guns in the house.

Panzuto confirmed there were none, and he surrendered quietly. None of his neighbours realised what had happened - or indeed who he was - until he was gone.

Amid the media frenzy that followed, a British court heard he was wanted for the Borelli murder and was linked to many others.

Gennaro Panzuto - with all his plans to make it big - didn’t fight extradition.

Back at the Caravan Park, Mick Bury was absolutely gob-smacked. “He nearly moved into my house in Blackpool as well,” he says.

Gennaro Panzuto, with the help of his British businessman host, had flitted around Lancashire, from the caravan park to Cock Robin Lane in Garstang. He would have no choice over his bed for the next 12 years.

The rising mafia boss was up for murder, and facing life in prison. Until he was offered the possibility of a new life - after release from prison.

But that would mean breaking the mafia code of silence - or Omertà.

Panzuto’s choice

The Italian justice system has operated a “state collaboration” system for more than 40 years. Mafia men and women can seek lesser sentences in return for evidence that will bring down their co-conspirators. They can ask to be relocated, and given a new identity.

Italians are divided over the wisdom of the programme - given that it allows some gangsters to evade full punishment for their crimes. But there is no doubt that it’s led to some remarkable successes in dismantling mafia gangs.

A state collaborator is colloquially called a “Pentito” - a Penitent.

This - eventually - was Panzuto’s choice.

“I chose my family”

“My girlfriend begged me to confess - to collaborate. I didn’t want to listen to her at first - but I was missing her deeply.

“And one day she went straight to the prosecutor’s office and said: ‘Let’s go see Gennaro. I will convince him to collaborate.’”

Michele Del Prete was sceptical. Was Panzuto really going to confess, or was it a ruse to avoid a long sentence.

“I was very strict in my initial judgment of this collaboration,” he says.

“We’re talking about someone who has committed very serious crimes. Therefore it is up to us prosecutors to be very careful, and evaluate [the value] of the contribution.”

Michele Del Prete, anti-mafia prosecutor

Gennaro Panzuto was being held far from Naples. And that distance gave him time to think.

“The only good thing about hard time in prison is that you can reflect long and hard - you’re going deep inside.

“And when you go that deep, it’s not difficult to ask myself: ‘Do I need to now spend my life in prison - and if so, who am I doing this for?’ I chose my family.”

Panzuto agreed to be a collaborator. Over the course of several interviews with Michele Del Prete he named names, events and crimes; murders and murderers; drug traffickers and extortion gangs; robbers and leaders; arsonists and thieves.

And he told the prosecutors everything about his British associates. He told them about the scams - the name of the businessman, his bent lawyer and his dodgy accountant.

Michele Del Prete passed to the UK all the information about Panzuto’s British businessman host.

“I remember the British told us that [the businessman] was definitely involved in scams - they’d known about this character,” says Michele Del Prete.

“But his links with the Neapolitan Camorra - that was news to them. We don’t know what they did with the information.”

The BBC has learnt that Lancashire Police did open an investigation - but nobody will tell us what happened to it.

The force says there is nobody in post today who has knowledge of the Panzuto affair - one of the biggest organised crime catches in the region.

The British businessman who helped Panzuto is still out there today working scams - and we cannot name him for legal reasons.

Hunting

baby gangsters

Back in Naples, the police squeezed every drop out of Panzuto’s evidence, and his confessions have helped put away a string of mafia men.

In return, Gennaro Panzuto was given a date when he would leave prison and have a chance at that new life.

In Naples, the state collaborator programme has been so successful that most of the Camorra’s experienced bosses are in jail.

But there is now a new threat. “Baby Gangs are now in the areas where there are no more historical clans,” says Pietro Ioia, the old crook who’s gone straight.

“They are young people, who take over the neighbourhood where there’s a power vacuum.

“They’re crazy loose cannons… shooting, shooting, shooting. Young people don’t discuss, they just shoot.”

I ask Giovanni Melillo, Naples’ chief prosecutor, how serious a threat the Baby Gangs are to his city now.

The Camorra clans are still the primary threat, he says. They’ve not gone away just because the state collaborator system has led to more bosses going to jail.

“What’s important to emphasise is precisely the ability to turn violence into business - criminal networks into business networks,” he says.

“Corruption and money laundering are powerful levers - much more important than the use of street violence.”

The kids in the Baby Gangs may think they’re top of the tree. But they are just one bullet away from being a footnote in the police archives. The real power still lies within deeper clan networks and the white-collar criminals who are hard to detect.

It’s easy to despair about all of this - and Alessandra Clemente has more cause than most to do so.

Alessandra Clemente

In 1997 her mother, Silvia Ruotolo, was gunned down in the street - a crime that shocked the nation.

The teacher was an innocent woman, walking home with her five-year-old son.

Today Clemente is a city councillor and one of the most well-known anti-mafia figures in Italy. She points to a piece of graffiti on the wall of the city council building where she works.

Anti-Camorra graffiti

It says “Camorra Merda” - “Camorra shit”. It’s been there for a few years.

“The graffiti was spontaneous,” she says.

“Naples is an anti-Camorra city. We can fight two ways: through the courts, through the culture.”

The solution, she says, is to find a way to offer hope and jobs.

“Every day we can take away the fuel of the Camorra - the young - by giving young people opportunities.”

Ioia is more downbeat. “The Camorra’s always here. It’s the cancer of our city.”

“I am as ashamed as a dog”

Gennaro Panzuto may leave jail as early as 2021, as part of his agreement with the Italian state.

But he will never set foot in Naples again. He will be relocated and, if necessary, be given a new identity.

At the beginning of our meeting, when I asked Panzuto if he had left his old life behind, he said he had “changed his skin”.

“I’m going to tell you the truth. I repented for love. For the love of my partner - for the love of my children.”

Panzuto tells me he is in an “existential crisis” - not knowing his true self anymore.

He showed me the marks on his body from acts of self-harm in prison. He has paid a high personal price for breaking the code of silence.

“You never get to forget one single day the choice you made, the codes you violated, the people you let down.

“I have a brother and three sisters. I have not seen or heard from them since I became a collaborator.”

What about the cost to the families of his victims? Does he not think about that, rather than himself?

“I am as ashamed as a dog. Murdering people doesn’t take anything - it just takes great cowardice. That’s all.”

Author: Dominic Casciani

Field producer: Steve Swann

Film camera: Tony Dolce

Video editor: Alex Dackevych

Graphics: Salim Qurashi

Online producer: Paul Kerley

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Author: Dominic Casciani

Field producer: Steve Swann

Film camera: Tony Dolce

Video editor: Alex Dackevych

Graphics: Salim Qurashi

Online producer: Paul Kerley

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Maps: Google

Graziano Borelli images: Simone Di Meo

Lancashire countryside image: Alamy

Thanks to Dr Felia Allum, University of Bath

Dominic Casciani can be contacted in confidence at dominic.casciani@bbc.co.uk

Or via a DM on Twitter https://twitter.com/BBCDomC

Published Friday 14 February 2020

Our World - Confessions of a Mafia Killer

On the BBC News Channel:

Sat 15 Feb 2020 - 04:30, 21:30

Sun 16 Feb 2020 - 03:30, 21:30

Or view online

More long reads

Dyatlov Pass: Why did nine people die mysteriously?

Carbon-neutral in 15 years: The country with an ambitious plan