The man who talked to chairs

And how he found a new lease of life

The man who

talked to chairs

And how he found

a new lease of life

by Sean Coughlan

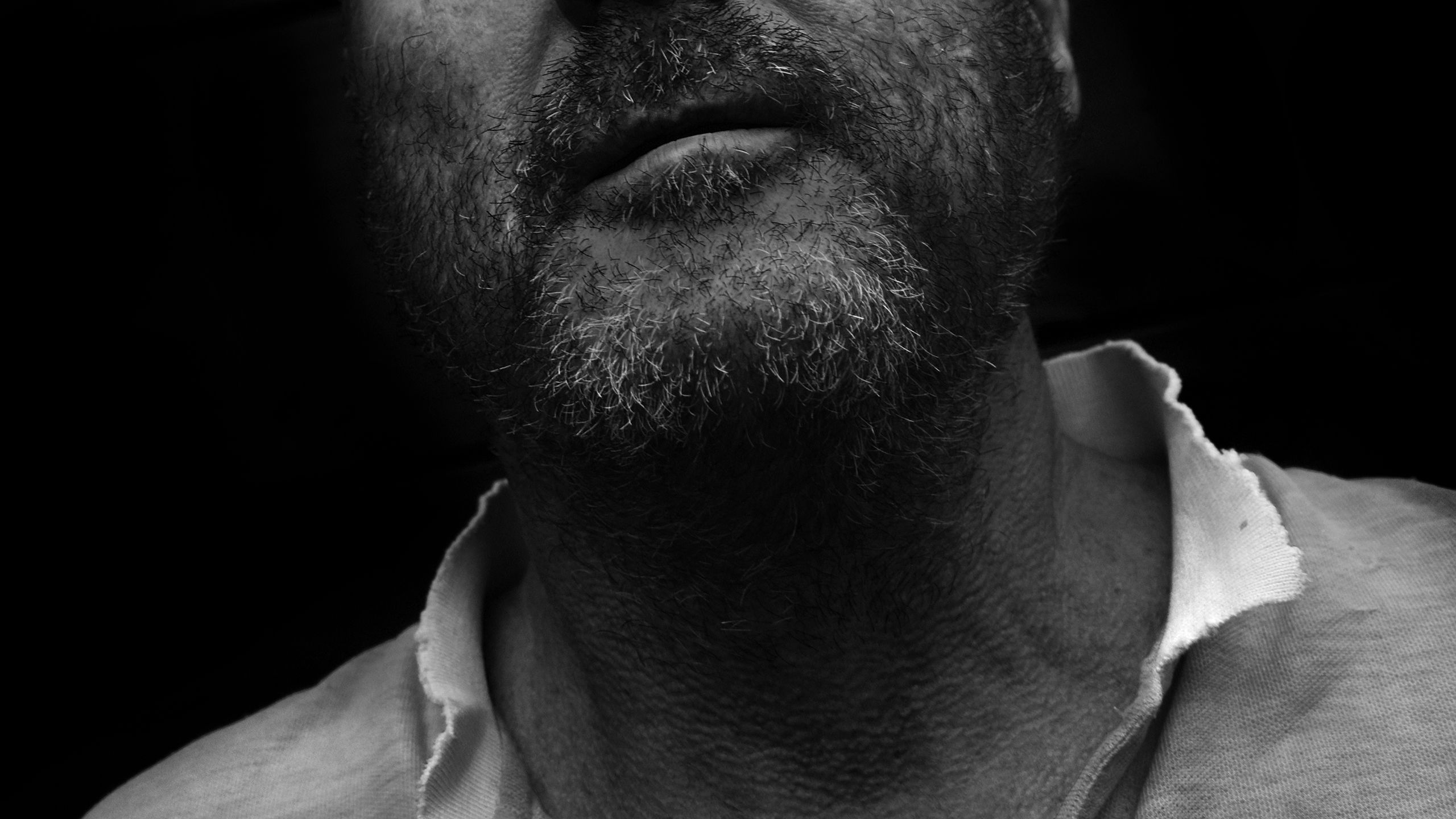

“I was having discussions with chairs,” says Shane Cocker, itching with nervous energy. “I was thinking why don’t you answer me?”

“You’re stuck in four walls and you see nobody. You get up the next day and who do you see? Nobody,” says the 56-year-old from Dewsbury in West Yorkshire, describing the corrosive, creeping ache of lockdown loneliness.

Shane, an unemployed lorry driver, was isolated. Missing his mother who had died, but stoppered up by a lifetime of being told to “man up”.

“You don’t want to admit there’s a problem, and then things just get worse and worse. You give up on everything,” he says, tightening his fists at the thought of it.

“I was literally just sat there. I got scruffy, I got irritable, I was eating but not properly, I wasn’t able to sleep. I was in denial about everything.”

It’s a problem shared by millions during the pandemic. The week when the clocks went back, with evenings getting darker earlier, saw the highest recorded levels of extreme loneliness, since the lockdown began in March.

More than four million people were in the category of “always or often” lonely in the week up to 1 November, according to Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures - more than 60% higher than typical pre-lockdown levels.

Shane says he could go a fortnight without talking to anyone. “It was a vicious circle.”

Social distancing has the best of intentions, but it’s also a slow starvation of the senses. And with winter approaching and the latest restrictions, more people than ever are struggling with this enforced separation. Love will tear us - two metres - apart again.

For Shane, it got darker before it got better, much better.

“I had nothing at all. I was just ready to jump off the bridge. That was close, very, very close. I’d even decided where I was going to go,” he says quietly.

But he’s in a hurry this autumn Friday afternoon, because he’s got people who need his help, and he’s laughing. This isn’t a story about despair, it’s about getting things fixed.

A bit of Huddersfield appears as he opens the front door to leave this unusual place.

“It’s the Bee Gees story,” he shouts over his shoulder. “We’ve done the Tragedy. Now we’re Stayin’ Alive.”

“I was having discussions with chairs,” says Shane Cocker, itching with nervous energy. “I was thinking why don’t you answer me?”

“You’re stuck in four walls and you see nobody. You get up the next day and who do you see? Nobody,” says the 56-year-old from Dewsbury in West Yorkshire, describing the corrosive, creeping ache of lockdown loneliness.

Shane, an unemployed lorry driver, was isolated. Missing his mother who had died, but stoppered up by a lifetime of being told to “man up”.

“You don’t want to admit there’s a problem, and then things just get worse and worse. You give up on everything,” he says, tightening his fists at the thought of it.

“I was literally just sat there. I got scruffy, I got irritable, I was eating but not properly, I wasn’t able to sleep. I was in denial about everything.”

It’s a problem shared by millions during the pandemic. The week when the clocks went back, with evenings getting darker earlier, saw the highest recorded levels of extreme loneliness, since the lockdown began in March.

More than four million people were in the category of “always or often” lonely in the week up to 1 November, according to Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures - more than 60% higher than typical pre-lockdown levels.

Shane says he could go a fortnight without talking to anyone. “It was a vicious circle.”

Social distancing has the best of intentions, but it’s also a slow starvation of the senses. And with winter approaching and the latest restrictions, more people than ever are struggling with this enforced separation. Love will tear us - two metres - apart again.

For Shane, it got darker before it got better, much better.

“I had nothing at all. I was just ready to jump off the bridge. That was close, very, very close. I’d even decided where I was going to go,” he says quietly.

But he’s in a hurry this autumn Friday afternoon, because he’s got people who need his help, and he’s laughing. This isn’t a story about despair, it’s about getting things fixed.

A bit of Huddersfield appears as he opens the front door to leave this unusual place.

“It’s the Bee Gees story,” he shouts over his shoulder. “We’ve done the Tragedy. Now we’re Stayin’ Alive.”

If Harry Potter had his Platform 9 3/4 for his magic journeys, Huddersfield has its Platform 1.

It’s a charity project so called, with Yorkshire literalness, because it’s right beside the town’s railway station.

But any commuters looking inside, and seeing Shane and his mates bustling and joking around, are unlikely to see the deadly seriousness of what happens here - and why Friday night has such an uncomfortable significance.

This tiny, gritty charity has had to respond to 15 suicide attempts during the pandemic - compared with one for all of last year.

The project is on a sliver of ground, with ramshackle offices and a couple of repurposed 1950s railway carriages, that has become a haven for 500 lonely, socially-disconnected men in this part of Yorkshire.

Even in the lockdown, there is still a constant flow of people coming in and out. There are work tools, bikes being repaired, a vegetable patch with cabbages, cups of tea being ferried.

A big old clock face lies on the ground, maybe where time was literally hanging too heavily.

People can turn up without any appointment and get help, advice and company. Shane, himself, fixes bikes for key workers, chats to his friends, and then delivers food to people who cannot get out of their own houses.

“It gives us a purpose,” he says, re-energised by the idea of reaching people stuck at home the way he was before. He’s got back his self-esteem and wants to pass on the sense of hope to others still struggling to find theirs.

Throughout the pandemic, between two and three million adults have not left their home for any reason during the previous seven days, for even shopping or walking, according to ONS figures.

If Harry Potter had his Platform 9 3/4 for his magic journeys, Huddersfield has its Platform 1.

It’s a charity project so called, with Yorkshire literalness, because it’s right beside the town’s railway station.

But any commuters looking inside, and seeing Shane and his mates bustling and joking around, are unlikely to see the deadly seriousness of what happens here - and why Friday night has such an uncomfortable significance.

This tiny, gritty charity has had to respond to 15 suicide attempts during the pandemic - compared with one for all of last year.

The project is on a sliver of ground, with ramshackle offices and a couple of repurposed 1950s railway carriages, that has become a haven for 500 lonely, socially-disconnected men in this part of Yorkshire.

Even in the lockdown, there is still a constant flow of people coming in and out. There are work tools, bikes being repaired, a vegetable patch with cabbages, cups of tea being ferried.

A big old clock face lies on the ground, maybe where time was literally hanging too heavily.

People can turn up without any appointment and get help, advice and company. Shane, himself, fixes bikes for key workers, chats to his friends, and then delivers food to people who cannot get out of their own houses.

“It gives us a purpose,” he says, re-energised by the idea of reaching people stuck at home the way he was before. He’s got back his self-esteem and wants to pass on the sense of hope to others still struggling to find theirs.

Throughout the pandemic, between two and three million adults have not left their home for any reason during the previous seven days, for even shopping or walking, according to ONS figures.

“The problem is getting a lot worse,” says Bob Morse, who runs Platform 1 with Jez Walsh. They are the two grizzled godfathers of this rescue mission.

“The need is so intense. You get people getting off the train saying, ‘Here I am, can you help?’,” says 71-year-old Bob. He’s furious that so many people are out there, lost in what he calls “the void”.

Information and support

If you need support for emotional distress, or you know someone else who does, these organisations may be able to help.

“They are lonely, isolated, in danger of depression and anxiety; people who have been self-medicating; people who have lost loved ones and need some connection,” he says.

The project is aimed at helping older men - who are among the most vulnerable to getting cut off and least likely to seek help.

“There’s the stereotype of maleness, the stigma of weakness. They’ve been toughing it out. Get over it. Have another drink. Get another bottle,” says Bob. And he’s quick to admit that he has had problems with drink and mental health himself - and so speaks from a position of knowing what it’s like.

Before the lockdown, the typical visitor would have been in their 40s, often out of work, without qualifications, living alone, with no spare cash and without access to the internet. They were people that the modern world had built a bypass around.

The lockdown has radically changed who now needs help.

“The people who are coming to us now are completely different. More professional people. It’s become massive,” says Jez, a feisty 61 year old running an accidental emergency service.

“A lot of people who are now in crisis wouldn’t have been before,” says Bob. “They would have been in a work environment and that would have solved a lot of issues about loneliness and connection.”

There are more younger people living alone, often dependent on work for their social connections - and whether they have lost their jobs, had their working hours reduced or are working from home, they risk becoming the “new lonely”. The current restrictions, when you can’t even go for a drink or a meal with friends, make it even harder.

Jez talks about how workplaces are often no longer communities offering companionship and support. Mining in this area is now a day trip to a nearby mining museum.

“People are distrustful of each other.” He taps a laptop and says people want contact and people to confide in, not social media. “You’ve got millions of strangers pretending to be friends.”

Shane explains how loneliness can come down like a sudden nightfall.

He’d looked after his grandmother until she’d died - and then his mother had been taken to hospital. He was worried about going to visit her, because he had to tell her their dog had died.

Instead he was the one who got bad news.

“Your mother’s got four days,” he said a doctor told him. “I said ‘No, you’re wrong. You are wrong, mate.’ So within a week I was there on my own. What was I going to do?”

In the background there are phone conversations going on all the time. At their centre is the third part of this charity trinity, Bridget Fahy, a 49 year old whose quiet voice has literally become a matter of life and death.

“It’s Friday,” says Jez, who has been keeping an ear to the phone conversations. “The witching hour.”

Almost all the attempted suicides here have been late on a Friday night - starting with Bridget getting a phone call.

“It’s the fear of the weekend, that extra loneliness,” says Bridget.

“You get a phone call where you pick up the phone and all you can hear is a man sobbing at the other end,” says Jez.

“And you say, ‘Who is it?’ - and they say, ‘I just want to thank you for everything’.”

While Bridget tries to talk to the callers - and it’s her they’ve usually chosen to contact - the police and ambulance services are alerted. Then Bridget and Jez scramble in their cars to reach the person who has rung.

Their recent Friday night was talking down a man armed with a weapon and a fighting dog, while keeping the police at a distance.

Neither of them expected to be doing this - but it’s been their experience of the lockdown.

“There’s something wrong when a man I’ve only known a month puts me down as next of kin,” says Jez.

Shane explains how loneliness can come down like a sudden nightfall.

He’d looked after his grandmother until she’d died - and then his mother had been taken to hospital. He was worried about going to visit her, because he had to tell her their dog had died.

Instead he was the one who got bad news.

“Your mother’s got four days,” he said a doctor told him. “I said ‘No, you’re wrong. You are wrong, mate.’ So within a week I was there on my own. What was I going to do?”

In the background there are phone conversations going on all the time. At their centre is the third part of this charity trinity, Bridget Fahy, a 49 year old whose quiet voice has literally become a matter of life and death.

“It’s Friday,” says Jez, who has been keeping an ear to the phone conversations. “The witching hour.”

Almost all the attempted suicides here have been late on a Friday night - starting with Bridget getting a phone call.

“It’s the fear of the weekend, that extra loneliness,” says Bridget.

“You get a phone call where you pick up the phone and all you can hear is a man sobbing at the other end,” says Jez.

“And you say, ‘Who is it?’ - and they say, ‘I just want to thank you for everything’.”

While Bridget tries to talk to the callers - and it’s her they’ve usually chosen to contact - the police and ambulance services are alerted. Then Bridget and Jez scramble in their cars to reach the person who has rung.

Their recent Friday night was talking down a man armed with a weapon and a fighting dog, while keeping the police at a distance.

Neither of them expected to be doing this - but it’s been their experience of the lockdown.

“There’s something wrong when a man I’ve only known a month puts me down as next of kin,” says Jez.

“I have a confession to make. This is the only data that’s ever made me cry,” says Professor Sarah Garfinkel.

And when a neuroscientist who “loves scanning brains” starts to cry over research data about loneliness you know it’s something serious.

“I think it is devastating - we’re social beings, we should be together in groups,” says the professor of cognitive neuroscience at University College London.

She has been researching what isolation does to people - and she is passionate that loneliness isn’t seen as something poignant but unimportant.

Isolation, which might be interwoven with depression and anxiety, is extremely bad for your health, she says, increasing stress and raising the risk of strokes, heart attacks and ultimately premature death.

“When you compare loneliness to other risk factors it’s actually one of the more dominant ones,” she says.

Prof Garfinkel warns that loneliness can lead to other destructive “comfort” behaviour such as drinking too much alcohol or over eating. And loneliness goes hand-in-exhausted-hand with not being able to sleep.

Prof Garfinkel is trying to look after her own young university students during the pandemic and is desperately worried about them suffering from loneliness and being “stuck on their own”.

The pandemic and isolation on such a big scale runs against all our human needs, she says, and our instincts to “huddle together” when facing dangers.

Much communication has been switched online, but she says Zoom meetings are a poor substitute for the social benefits of being in company.

This might be in a way that we don’t even realise, says Prof Garfinkel. For instance, the size of someone’s pupils might subtly mirror those of another person speaking to them, sending out signals of empathy. With the postage stamp heads on a Zoom meeting that’s impossible and you’re left with a feeling of talking to someone who is not emotionally responding.

If loneliness is a serious health problem - then there is an awful lot of it about.

It’s like a cobweb getting strung wider and wider. The elderly. Carers. Those shielding. Students. Mothers with young babies. The bereaved. Single people cut off from social lives. Young adults working from home. People with mental health problems. Those cut off in care homes. People with disabilities. Mourners having to sit physically apart at a funeral. Families waving at relatives through glass.

It’s not even just about being alone. The pandemic tracking figures show that while some people are suffering from spending too much time on their own, others are miserable from never getting any time to themselves. Loneliness, as well as hell, can be other people.

Study after study shows young people feel loneliness more acutely than any other group - they’re aching to get out and connect with friends and have missed so many big bonding events this year, whether it was a school prom, graduation, birthday parties or post-exam festivals.

Covid is also the great divider, magnifying differences - and loneliness is not shared evenly. A study from YouGov shows a clear social gap, with poorer people much more likely to be lonely. Renters have higher levels of loneliness than homeowners.

Whatever the combination of factors, the start of November saw the highest peak so far in levels of adults who are “always or often” lonely - coinciding with the arrival of longer winter evenings.

According to the ONS, in the week up to 1 November there were 4.2 million adults across Britain in this category - compared with 2.6 million in parts of the summer and before the pandemic.

These numbers fluctuate and are nudging down from that peak - but the overall trend has shown loneliness at high levels as the seasons change.

In August, the broader measure of loneliness, including those who are “sometimes” lonely stood at about 10 million adults - and that had risen to about 14 million in October and November, with the latest figure at about 12.5 million.

If those who are “occasionally” lonely are included it’s about half the adult population.

Dr Vivian Hill, who has researched isolation in the pandemic for the British Psychological Society, thinks the “descent into winter” is a “very significant factor”, with the weather making it difficult to get outside.

But she says loneliness is something that we should be optimistic about tackling.

“Many people have adapted, we’re very resilient - and we’ve found other ways to make those social connections,” says Dr Hill.

But she says it’s vital to support those people for whom isolation in the pandemic has been a “catastrophe” - and these might be specific groups, such as people with autism whose usual social networks might be out of reach.

There have been distinct waves of loneliness during the pandemic, says Daisy Fancourt, associate professor of psychobiology at University College London.

And contrary to what might have been expected, the first lockdown in March did not trigger a great surge of loneliness.

“Everyone was in the same boat,” says Dr Fancourt, with people feeling part of a great collective effort - clapping on doorsteps and Zoom quizzes.

But she says the psychological toll is building up. People are fearful about jobs and money and collectively there are worries gathering below the surface.

This sense of burn out is backed by another tracking survey of morale in the pandemic, with the ONS asking people how satisfied they feel with their lives - and the week to 1 November was the lowest it has ever been since it began in March.

Baroness Barran, the Minister for Loneliness, puts it simply: “People are tired.”

She says the collective mood towards the pandemic has been through its initial “heroic” phase and has the challenge of a phase of “disillusionment”, made more difficult with “shorter days and longer nights”.

She says talking to people looking after relatives with dementia, isolated during the pandemic, had been one of the “most painful conversations I’ve had this year”.

When Shane opens the front door from Platform 1, the square outside Huddersfield station is almost empty.

It’s Covid quiet. The Head of Steam pub is silent and the bronze statue to local boy Harold Wilson is looking out on streets that look weary in the latest lockdown. The pawnbrokers round the corner has a “To Let” sign up.

But people are still people and, given a chance, they’ll help others.

“When I first went to Platform 1 I wouldn’t talk to anybody,” says Shane. “I just didn’t have the confidence. I’d be stood there stuttering and stammering.”

It took him six weeks to come back to life, getting involved in some of the activities here, talking to people, making and repairing things, playing chess, going on trips, gardening.

And he’s gone from getting help to being the helper, an ebullient voice for the possibility of change.

Shane keeps making the point that there is an answer - there are positive ways of getting support - and there is no need to “totally lose the plot and refuse to come out of the house”.

“Rather than talking to chairs and slowly going round the bend you can come in here and you’re not on your own,” he says.

But men in particular have to admit to their problems - and need to let the tears start to flow, says Shane.

“It’s meant to be unmanly. But it’s not. Now I say, ‘Come in and have a cry. And we turn it around and have a laugh.”

Shane says he met Baroness Barran on a visit to Huddersfield and bent her ear to say he thought there should be more practical approaches to tackle loneliness - such as subsidising bus passes so that people can get to places like Platform 1.

She isn’t short of people offering suggestions. She says her ministerial email in-box is filled with a “mixture of lots of people talking about their own ideas of how to help - and others saying how desperately lonely and isolated they feel”.

Her department is giving grants to “hyperlocal” community projects that help people to connect with each other.

Services can be thinly stretched though. Another middle-aged visitor to Platform 1, a recovering addict trying to reconnect with his family, says he had a “breakdown” during the lockdown and was self-harming. He ended up being treated hundreds of miles away in Surrey.

And as he says, that trip cost much more than a bus pass.

When Shane opens the front door from Platform 1, the square outside Huddersfield station is almost empty.

It’s Covid quiet. The Head of Steam pub is silent and the bronze statue to local boy Harold Wilson is looking out on streets that look weary in the latest lockdown. The pawnbrokers round the corner has a “To Let” sign up.

But people are still people and, given a chance, they’ll help others.

“When I first went to Platform 1 I wouldn’t talk to anybody,” says Shane. “I just didn’t have the confidence. I’d be stood there stuttering and stammering.”

It took him six weeks to come back to life, getting involved in some of the activities here, talking to people, making and repairing things, playing chess, going on trips, gardening.

And he’s gone from getting help to being the helper, an ebullient voice for the possibility of change.

Shane keeps making the point that there is an answer - there are positive ways of getting support - and there is no need to “totally lose the plot and refuse to come out of the house”.

“Rather than talking to chairs and slowly going round the bend you can come in here and you’re not on your own,” he says.

But men in particular have to admit to their problems - and need to let the tears start to flow, says Shane.

“It’s meant to be unmanly. But it’s not. Now I say, ‘Come in and have a cry. And we turn it around and have a laugh.”

Shane says he met Baroness Barran on a visit to Huddersfield and bent her ear to say he thought there should be more practical approaches to tackle loneliness - such as subsidising bus passes so that people can get to places like Platform 1.

She isn’t short of people offering suggestions. She says her ministerial email in-box is filled with a “mixture of lots of people talking about their own ideas of how to help - and others saying how desperately lonely and isolated they feel”.

Her department is giving grants to “hyperlocal” community projects that help people to connect with each other.

Services can be thinly stretched though. Another middle-aged visitor to Platform 1, a recovering addict trying to reconnect with his family, says he had a “breakdown” during the lockdown and was self-harming. He ended up being treated hundreds of miles away in Surrey.

And as he says, that trip cost much more than a bus pass.

Bob Morse, station master of Platform 1’s efforts, says: “We have got lot of people now who are not connected anywhere.

“But miraculously we’ve found we can actually turn the situation around. Often it’s the fact they have someone to talk to, somewhere to go. A smile and a cup of coffee are absolutely priceless,” says Bob.

“It’s so rewarding when you hear someone say I wouldn’t do that if you hadn’t been there,” says Shane.

Every one of those 15 people who had attempted suicide were reached in time.

It’s getting darker in Huddersfield. The nights are coming in fast. The shops are missing their customers, the roads are missing traffic and people are desperately missing each other.

AUTHOR: Sean Coughlan

EDITOR: Kathryn Westcott

PICTURE EDITOR & PRODUCTION: Emma Lynch