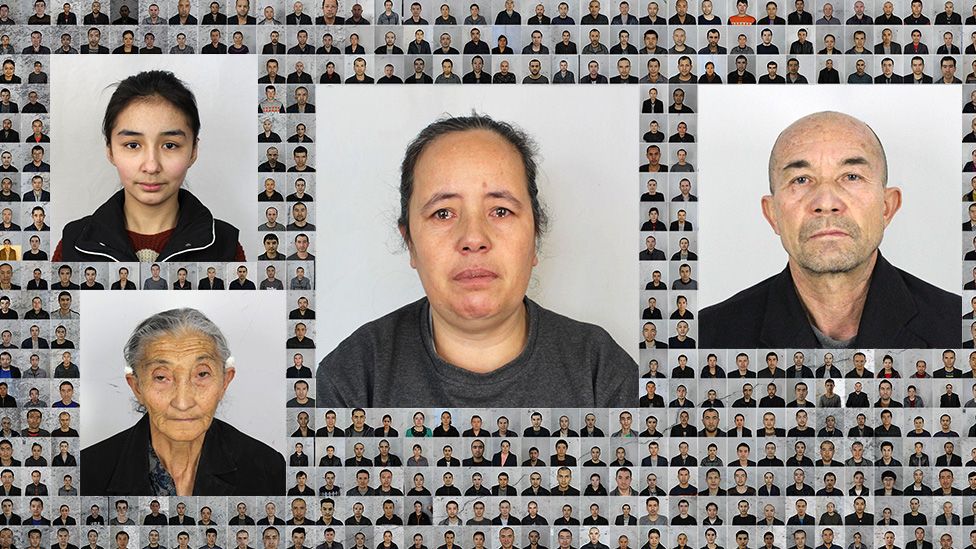

For months, the BBC has been communicating in secret with three North Koreans living in the country. They expose, for the first time, the disaster unfolding there since the government sealed the borders more than three years ago.

Starvation, brutal crackdowns, and no chance to escape.

We have changed their names to protect them.

Myong Suk

Myong Suk

Myong Suk is hunched over her phone, desperately trying to make another sale. A shrewd businesswoman, she is secretly selling minuscule amounts of smuggled medicine to those who desperately need it - just enough so she can survive the day. She has already been caught once and could barely afford the bribe to stay out of prison. She cannot afford to be caught again. But at any moment there could be a knock on the door. It is not just the police she fears, it’s her neighbours. There is now almost no-one she can trust.

This is not how it used to be.

Myong Suk’s medicine business used to be thriving.

Myong Suk: “I tried to smuggle, but I got caught”

Myong Suk: “I tried to smuggle, but I got caught”

But on 27 January 2020 North Korea slammed shut its border in response to the pandemic, stopping not just people, but food and goods, from entering the country. Its citizens, who were already banned from leaving, have been confined to their towns. Aid workers and diplomats have packed up and left. Guards are under order to shoot anyone even approaching the border. The world’s most isolated country has become an information black hole.

Under the tyrannical rule of Kim Jong Un, North Koreans are forbidden from making contact with the outside world. With the help of the organisation Daily NK, which operates a network of sources inside the country, the BBC has been able to communicate with three ordinary people. They are eager to tell the world about the catastrophic toll the border closure has taken on their lives. They understand if the government discovers they are talking to us, they would likely be killed. To protect them, we can only reveal some of what they have told us, yet their experiences offer an exclusive snapshot of the situation unfolding inside North Korea.

“Our food situation has never been this bad,” Myong Suk tells us.

Like most women in North Korea, she is the main earner in the family. The meagre wages men earn in their compulsory state jobs are all but worthless, forcing their wives to find creative ways to make a living.

Before the border closure, Myong Suk would arrange for much-needed drugs, including antibiotics, to be smuggled across from China, which she would sell at her local market. She needed to bribe the border guards, which ate up more than half of her profits, but she accepted this as part of the game. It allowed her to live a comfortable life in her town in the north of the country, along the vast border with China.

The responsibility to provide for her family has always caused her some stress, but now it consumes her. It has become nearly impossible to get hold of products to sell.

Once, in desperation, she tried to smuggle the medicine herself, but was caught, and now she is monitored constantly. She has tried selling North Korean medicine instead, but even that is hard to find these days, meaning her earnings have halved.

Now when her husband and children wake, she prepares them a breakfast of corn. Gone are the days they could eat plain rice. Her hungry neighbours have started knocking at the door asking for food, but she has to turn them away.

“We are living on the front line of life,” she says.

In a town elsewhere on the border, Chan Ho, a head-strong construction worker, is having a frustrating morning. “I want people to know that I am regretting being born in this country,” he vents.

He is up early again to help his wife set up for the market, before heading to the construction site. He dutifully carries her products and loads them on to her stall, fully aware that her business is the only reason he is still alive. The 4,000 won he makes a day - the equivalent of $0.50 (£0.40) - is no longer enough to buy one kilo of rice, and it has been so long since his family received government food rations, he has forgotten about them.

The markets, where most North Koreans buy their food, are now almost empty, he says, and the price of rice, corn and seasonings has soared.

Because North Korea does not produce enough food to feed its people, it relies on imports. In sealing the border, the government cut off vital supplies of food, along with the fertiliser and machinery needed to grow crops.

Chan Ho: “When they closed the border, everything became scarce”

Chan Ho: “When they closed the border, everything became scarce”

At first Chan Ho was afraid he might die from Covid, but as time went on, he began to worry about starving to death, especially as he watched those around him die.

The first family in his village to succumb to starvation was a mother and her children. She had become too sick to work. Her children kept her alive for as long as they could by begging for food, but in the end all three died. Next came a mother who was sentenced to hard labour for violating quarantine rules. She and her son starved to death.

More recently, one of his acquaintance's sons was released from the military because he was malnourished. Chan Ho remembers his face suddenly bloating. Within a week he had died.

“I can’t sleep when I think about my children, having to live forever in this hopeless hell,” he says.

Ji Yeon

Ji Yeon

Hundreds of miles away, in the relative affluence of the capital Pyongyang, where tower blocks line the city’s river, Ji Yeon rides the subway to work. She is exhausted, after a similarly sleepless night.

She has two children and her husband to support with the pennies she makes working in a food shop.

She used to sneak fruit and vegetables out of the shop to sell at the market, alongside cigarettes her husband received in bribes from his co-workers. She would buy rice with the money. Now her bags are thoroughly searched when she leaves, and her husband’s bribes have stopped coming. No-one can afford to give anything away.

“They’ve made it impossible to have a side-hustle,” she frets.

Ji Yeon now goes about her day pretending she has eaten three meals, when in truth she has eaten one. Hunger she can endure. It is better than having people know she is poor.

She is haunted by the week she was forced to eat puljuk – a mash of vegetables, plants and grass, ground into a porridge-like paste. The meal is synonymous with the very bleakest time in North Korea’s history – the devastating famine that ravaged the country in the 1990s, killing as many as three million people.

Ji Yeon: “I know one family that starved to death at home”

Ji Yeon: “I know one family that starved to death at home”

“We survive by thinking 10 days ahead, then another 10, thinking that if my husband and I starve, at least we will feed our kids,” Ji Yeon says. Recently she went two days without food.

“I thought I was going to die in my sleep and not wake up in the morning,” she says.

Despite her own hardship, Ji Yeon looks out for those worse off. There are more beggars now, and she stops to check on the ones lying down, but usually finds they are dead. One day she knocked on her neighbour’s door to give them water, but there was no answer. When the authorities went inside three days later, they discovered the whole family had starved to death.

“It’s a disaster,” she says. “With no supplies coming from the border, people do not know how to make a living.” Recently she has heard of people killing themselves at home, while others disappear into the mountains to die. She deplores the ruthless mentality that has blanketed the city.

“Even if people die next door, you only think about yourself. It’s heartless.”

Masked citizens wait for a train to pass at a crossing in Phyongysong, North Korea

Masked citizens wait for a train to pass at a crossing in Phyongysong, North Korea

Children run towards a train crossing in north-eastern North Korea

Children run towards a train crossing in north-eastern North Korea

An agitprop vehicle parked near a group of workers, North Korea

An agitprop vehicle parked near a group of workers, North Korea

Rare photos taken inside North Korea during the pandemic, NK News

Rare photos taken inside North Korea during the pandemic, NK News

Masked citizens wait for a train to pass at a crossing in Phyongysong, North Korea

Masked citizens wait for a train to pass at a crossing in Phyongysong, North Korea

Children run towards a train crossing in north-eastern North Korea

Children run towards a train crossing in north-eastern North Korea

An agitprop vehicle parked near a group of workers, North Korea

An agitprop vehicle parked near a group of workers, North Korea

Rare photos taken inside North Korea during the pandemic, NK News

Rare photos taken inside North Korea during the pandemic, NK News

For months, rumours have been swirling that people are starving to death, prompting fears North Korea could be on the brink of another famine. The economist Peter Ward, who studies North Korea, describes these accounts as “very concerning”.

“It’s all well and good to say you’ve heard about people starving to death, but when you actually know people in your immediate vicinity who are starving, this implies the food situation is very serious - more serious than we realised and worse than it has been since the famine in the late 1990s,” he says.

Emaciated brother and sister

Emaciated brother and sister

Archive images from North Korea’s famine in the 1990s

Archive images from North Korea’s famine in the 1990s

Archive images from North Korea’s famine in the 1990s

Archive images from North Korea’s famine in the 1990s

The North Korean famine marked a turning point in the country’s relatively short history, sparking a breakdown in its rigid social order. The state, unable to feed people, gave them fragments of freedom to do what they needed to survive. Thousands fled the country, and found refuge in South Korea, Europe, or the United States.

Meanwhile, private markets blossomed, as women began selling everything from soybeans, to used clothes and Chinese electronics. An informal economy was born, and with it a whole generation of North Koreans who have learnt to live with little help from the state – capitalists thriving in a repressive communist country.

As the market empties out for the day, and Myong Suk counts her reduced earnings, she worries the state is coming after her and this capitalist generation. The pandemic, she believes, has merely provided the authorities with the excuse to re-exert its diminished control over people’s lives. “Really they want to crack down on the smuggling and stop people escaping,” she says. “Now, if you even just approach the river to China, you’ll be given a harsh punishment.”

Chan Ho, the construction worker, is also nearing breaking point. This is the hardest period he has ever lived through. The famine was difficult, he says, but there were not these harsh crackdowns and punishments. “If people wanted to escape, the state couldn’t do much,” he says.

“Now, one wrong step and you’re facing execution.”

His friend’s son recently witnessed several executions carried out by the state. In each instance three to four people were killed. Their crime was trying to escape.

“If I live by the rules, I’ll probably starve to death, but just by trying to survive, I fear I could be arrested, branded a traitor, and killed,” Chan Ho tells us.

“We are stuck here, waiting to die.”

Before the border closure, more than 1,000 escapees used to arrive in South Korea every year, but since then only a handful are known to have fled and made it to safety in the South.

Satellite imagery, analysed by the NGO Human Rights Watch, shows that authorities have spent the past three years building multiple walls, fences and guard posts to fortify the border - making it almost impossible to flee.

7 May 2019

Satellite images show that in 2019 the border between North Korea and China had minimal fortifications.

19 March 2023

More recent satellite images show two walls and what look like a number of guard posts.

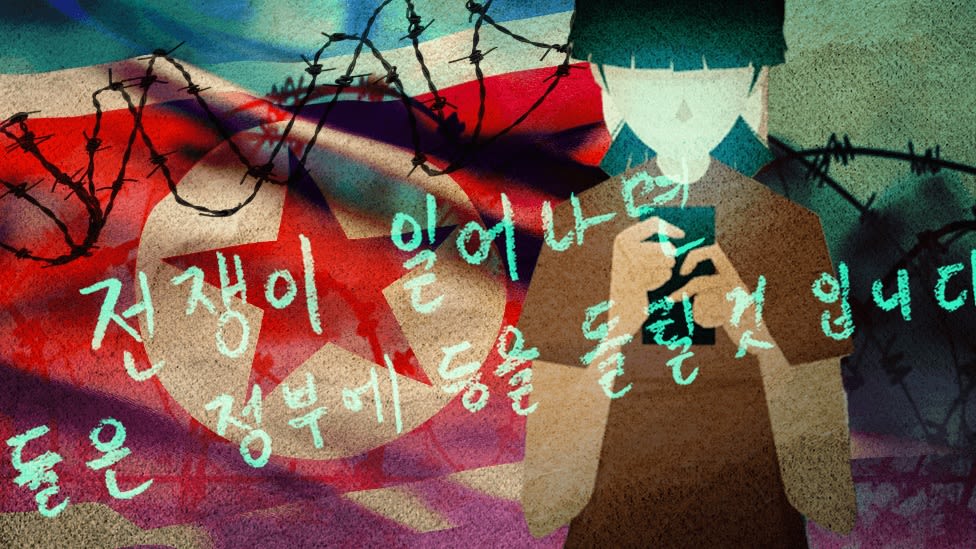

Merely trying to contact people outside the country is increasingly dangerous. In the past, residents near the border have been able to make secret phone calls abroad by connecting to Chinese mobile networks, using Chinese phones smuggled into the country. Now, at every community meeting, Chan Ho says anyone with a Chinese phone is told to turn themselves in. Recently Myong Suk’s acquaintance was caught talking to someone in China and was sent to a re-education prison for several years.

By cracking down on smuggling and people's connection to the outside world, the state is stripping its citizens of their ability to fend for themselves, says Hanna Song from the North Korean Database Centre for Human Rights (NKDB).

“At a time when food is already scarce, it is fully aware of the damage this will cause,” she says.

Yet these extreme controls could not keep coronavirus out. On 12 May 2022, almost two and a half years into the pandemic, North Korea confirmed its first official case.

With no means to test people, those with a fever were, in effect, locked in their homes for 10 days. They and their entire household were forbidden from taking a single step outside. As the outbreak spread, whole towns and streets were locked down, on some occasions for more than two weeks.

In Pyongyang, Ji Yeon watched from her window as some of her neighbours, who did not have enough food to last the lockdown, had vegetables put outside their door every other day. But up along the border there was no such help.

Myong Suk panicked. She was already living day to day, meaning her cupboards were empty. This is how she ended up frantically selling medicine in secret, convinced it would be better to earn money and risk catching the virus than risk starvation.

Chan Ho says five families were “half-dead” by the time they were released from a lockdown. They only survived by sneaking out to find food after dark. “Those strait-laced people who stayed at home could not survive,” he says.

“People were clamouring, saying they were going to starve, and for a few days the government released some emergency rice from its stockpiles.” There are reports that in some areas lockdowns were called off early when it became clear people would not otherwise survive.

Those who caught the virus could not rely on the country’s decrepit hospitals to treat them. Even basic medicine ran out. The official government advice was to use folk remedies to relieve symptoms. When Ji Yeon herself got sick, she desperately called her friends for tips. They recommended she drank boiling water infused with green onion roots.

According to Ji Yeon, many old people and children have died from Covid-19. In a country where an estimated 40% of the population is malnourished, health experts say it makes sense that, unlike in other countries, children fell sick. One of the city’s doctors told Ji Yeon that during the outbreak about one in 550 people in each neighbourhood in Pyongyang died. If extrapolated to the rest of the country, that would equate to more than 45,000 deaths - hundreds of times the official death toll of 74. But everyone was given an alternative cause of death, she was told, be it tuberculosis or liver cirrhosis.

In August 2022, three months after the outbreak, the government declared victory over the virus, claiming it had been eradicated from the country. Yet many of the quarantine measures and rules are still in place.

When Kim Jong Un sealed the border in such an extreme manner, he surprised the international community. North Korea is one of the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world, due to its pursuit of nuclear weapons. It is banned from selling its resources abroad, and unable to import the fuel it needs to function. Why, many asked, would a country already in economic ruin willingly inflict so much pain upon itself?

“I think the leaders decided that Covid-19 could kill a lot of people, or at least the wrong kinds of people, the people they feared dying,” says Peter Ward, referring to the military and elite who keep the Kim family in power. With one of the worst healthcare systems in the world, and a malnourished and unvaccinated population, it was reasonable to assume many would die.

But according to Hanna Song from NKDB, Covid has also presented Kim Jong Un with the perfect opportunity to re-exert control over people’s lives.

“This is what he has secretly wanted to do for a really long time,” she says. “His priority has always been to isolate and control his people as much as possible.”

After preparing and eating her meagre dinner, Ji Yeon washes the dishes and cleans her home once over with a damp towel. She climbs into bed early, hoping for a better night’s rest. She will probably manage more hours’ sleep than Chan Ho. Work is so busy now, he often has to sleep at his construction site.

But in the relative quiet of her border town, Myong Suk steals a moment to unwind, sitting with her family to watch TV, using a battery they have charged up during the day.

She particularly enjoys South Korean TV dramas, even though they are forbidden. The shows are smuggled across the border on micro-SD cards and sold in secret. The most recent release Myong Suk saw was about a K-pop star who shows up at his family’s house claiming to be their long-lost son. Since the border closure, hardly any new shows have made it into the country, she says. Plus, the crackdown has been so strong that people are being more careful.

She is referring to the Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act, passed in December 2020. Under this law, those who smuggle foreign videos into the country and distribute them can be executed. Chan Ho calls this “the scariest new law of all”. Merely watching the videos can lead to 10 years in prison. The purpose of the law, according to a copy of the text obtained by the news organisation Daily NK, is to prevent the spread of “a rotten ideology that depraves our society”.

North Korean propaganda video from late 2022 sourced by Daily NK

North Korean propaganda video from late 2022 sourced by Daily NK

The one thing Kim Jong Un is thought to fear above all else is his people learning about the prosperous and free world that exists outside their borders, and waking up to the lies they are being sold.

Chan Ho says since the law was passed, foreign videos have almost disappeared. Only the younger generation dares to watch them, causing their parents immense worry.

Ji Yeon recounts a recent public trial in Pyongyang. The local leaders were gathered to judge a 22-year-old man who had been sharing South Korean songs and films. He was sentenced to 10 years and three months in a hard-labour camp. Before 2020, Ji Yeon says this would have been a quiet trial, with perhaps one year in prison.

“People were shocked how much harsher the punishment was,” she says. “It’s so scary, the way they are targeting young people.”

Ryu Hyun Woo, a former North Korean diplomat who defected from the government in 2019, says the law was introduced to ensure young people’s loyalty, because they have grown up with such a different attitude from that of their parents. “We grew up receiving gifts from the state, but under Kim Jong Un the country has given people nothing,” he says. Young people now question what the country has ever done for them.

To enforce the law, the government has created groups that go around “ruthlessly” cracking down on anything deemed anti-socialist, says Ji Yeon. “People don’t trust each other now. The fear is great.”

Ji Yeon herself was taken in for questioning under the new law. Since her interrogation, she never reveals to others what she really thinks. She is more afraid of people now.

This erosion of trust concerns Prof Andrei Lankov, who has been studying North Korea for 40 years. “If people don’t trust each other, there is no starting point for resistance,” he says. “What that means is North Korea can stabilise and last for years and decades to come.”

In January 2023 the government passed yet another law, banning people from using words associated with the South Korean dialect. Breaking this law can, in the most extreme cases, also result in execution. Ji Yeon says there are now too many laws to remember, and that people are being taken away without even knowing which one they have supposedly violated. When they ask, the prosecutors simply respond by saying: “You don’t need to know which law you have broken.”

“What these three North Korean people have shared supports the incredible idea that North Korea is even more repressive and totalitarian than it has ever been before,” says Sokeel Park, from the organisation Liberty in North Korea, that helps North Korean escapees.

“This is devastating tragedy that is unfolding,” he says.

Recently there have been signs the authorities could be preparing to open the border. Myong Suk and Chan Ho, who live along the border, say most of those in their towns have now been vaccinated against Covid - with the Chinese vaccine they presume - while in Pyongyang, Ji Yeon says a good number of people have received two shots. Furthermore, customs data shows the country is once again allowing some grain and flour over the border from China, possibly in an attempt to ease shortages and stave off a much-feared famine.

But when North Korea finally decides to reopen, it is unlikely people’s old freedoms will be returned, says Chad O’Carroll, who runs the North Korea monitoring platform NK Pro.

“These systems of control that have emerged during the pandemic are likely to cement. This will make it harder for us to understand the country, and sadly much harder for North Koreans to understand what is happening outside of what they are told.”

There are small signs however that the regime will not emerge unscathed from the hardship it has inflicted on its people over the past three years.

Chan Ho says during the week, people do not think much about changing the system. They are so focused on finding one meal a day, simply happy to have food in front of them. But come the weekend, he, Myong Suk, and Ji Yeon have time to reflect.

They must attend their weekly Life Review Session, compulsory for every citizen. Here they admit to their mistakes and failures, whilst reporting the shortcomings of their neighbours. The sessions are designed to encourage good behaviour and root out dissidents. They could never admit to it in the classroom, but Chan Ho says people have stopped believing the propaganda on TV.

“The state tells us we are nestling in our mother’s bosom. But what kind of mother would execute their child in broad daylight for running to China because they were starving?” he asks.

“Before Covid, people viewed Kim Jong Un positively,” says Myong Suk, “but now almost everyone is full of discontent.”

North Korea: The Insiders

For more than three years, North Korea has sealed its borders. People are banned from leaving or entering the country. Almost every foreigner who was inside has packed up and left. Three people inside North Korea have risked their lives to tell the BBC what is happening.

Watch now on BBC iPlayer (UK Only)

Ji Yeon remembers when Kim Jong Un met President Trump in 2018, to negotiate giving up his nuclear weapons. She recalls being filled with hope and laughter, thinking perhaps she might soon be able to travel to foreign countries. The talks broke down, and since then Mr Kim has continued to spend his limited finances on improving his nuclear arsenal, spurning all offers of diplomacy from the international community. In 2022, he conducted a record number of missile tests.

“We were tricked,” says Ji Yeon. “This border closure has taken our lives back 20 years. We feel hugely betrayed.

“The people never wanted this endless weapons development, that brings hardship to generation after generation,” she laments.

Chan Ho blames the international community. “The US and UN seem half-witted,” he says, questioning why they still offer to negotiate with Kim Jong Un, when it is so clear he will not give up his weapons. Instead, the construction worker wishes the US would attack his country.

“Only with a war, and by getting rid of the entire leadership, can we survive,” he says. “Let’s end this one way or another.”

Myong Suk agrees. “If there was a war, people would turn their backs on our government,” she says. “That’s the reality.”

But Ji Yeon hopes for something simpler. She wants to live in a society where people don’t starve, where her neighbours are alive, and where they don’t have to spy on each other. And she wants to eat three meals of rice a day.

The last time we heard from her, she did not have enough to feed her child.

We put our findings to the North Korean (DPRK) government.

A representative from its embassy in London said: “The information you have collected is not entirely factual as it is derived from fabricated testimonies from anti-DPRK forces. The DPRK has always prioritised the interests of the people even at difficult times and has an unwavering commitment to the well-being of the people.

“The people’s well-being is our foremost priority, even in the face of trials and challenges.”

Read more:

Credits

Author: Jean Mackenzie

Producers: Hosu Lee and Won Jung Bae

Images: NK News, Maxar, Getty Images

The BBC would like to thank Lee Sang-Yong and the team at Daily NK for helping us to gather these interviews. We would also like to thank Chung Seung-Yeon and the team at NK News for helping us to verify some of our findings, and for providing us with photos and videos taken in North Korea.

Published 15 June 2023