Have rogue orcas really been attacking boats in the Atlantic?

In the past six months there have been at least 40 reported incidents involving orcas off the coasts of Spain and Portugal.

“I don’t frighten easily and this was terrifying,” skipper David Smith recalls of a late evening in October when his boat was approached by what looked at first like dolphins.

It quickly became apparent that they were much bigger than dolphins. And they were behaving very strangely.

“I looked at this animal - and it was jet black and brilliant white.”

For some two hours, a group of killer whales rammed the underside of the 45ft (13.7m) yacht he was sailing off the coast of Portugal.

“It was continuous,” he says. “I think there were six or seven animals, but it seemed like the juvenile ones - the smaller ones - were most active. They seemed to be going for the rudder, the wheel would just start spinning really fast every time there was an impact.”

David’s job, since he “quit the rat race to sail” back in 2013, is to deliver new boats to where their owners want them moored. In this case, he was part of a team delivering a catamaran from France to Gibraltar.

An hour before sunset, one of the crew called out.

“He said: ‘It looks like we have some large dolphins,’” recalls David.

The only other encounter he had had with an orca was more than 20 years ago in a Vancouver aquarium, but he was in no doubt that he was looking at a group of killer whales.

“They were right at the back of the boat.”

A sense of curiosity and excitement very quickly turned to fear when one orca disappeared beneath the boat and there was a loud thumping sound from the hull.

The boat was 20 miles (32.2km) off Porto, at least three hours from the Portuguese coast. With their VHF radio out of range, they had to use the satellite phone to contact the coastguard, who advised them to switch off the motor and take down the sails. Be as “uninteresting” as possible, they said.

“So then we were just drifting. But while I was on the phone I could hear them ramming the boat. At one point, one of the larger animals came right to the stern and flipped onto its back – you could see its bright white underside.”

The repeated thudding, unsettling as it was, was not David’s biggest fear. As the wheel spun back and forth, he thought the animals might be about to dislodge the rudder stock - a steering column through the hull of the boat.

“If that fractures, you’re really in trouble,” he says. “I was definitely preparing to ask the Portuguese coastguard to send a helicopter to get us off.”

The encounter is one of at least 40 similar incidents in the area. During the summer of 2020, the strangest of summers for so many of us, a group of killer whales off the coast of Spain and Portugal began to act very strangely indeed.

Accounts of the incidents suggested that the animals were deliberately targeting sailing boats. As David puts it: “They came to us, not the other way around.”

The first reported incident was back in July, the most recent at the end of October.

Behind international headlines about “rogue killer whales”, “orchestrated” orca attacks and the videos shared thousands of times on social media, there is a forensic marine science investigation that is still trying to work out what is driving these complex, intelligent and highly social marine mammals to behave in this way.

‘I just didn’t believe it’

As the light faded, the reverberating thuds from beneath the boat continued. Then David noticed the lights of a fishing boat in the distance.

“We put up the sail, with the idea that if things really went south, we would have another boat to jump onto.”

Finally, after two hours, as unexpectedly as it started, it all went quiet. No sound for five minutes, then nothing for 10. The wheel stopped spinning.

“After about an hour, we were confident they’d left us.”

The crew moved the boat closer to the coast - back within radio range. When they reached Gibraltar to carry out a more thorough check for damage, their boat became another piece of evidence in the ongoing investigation.

It's not unusual to see killer whales in these Atlantic waters. For millennia they have pursued their favourite prey, bluefin tuna, as the fish migrate along the hundreds of miles of Portuguese and Spanish coast, and through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, to breed in warmer Mediterranean waters.

Humans’ relationship with these orcas though has been on a knife-edge ever since we started fishing for more of that highly prized and highly priced bluefin tuna than appears to have been sustainable.

Some 60 killer whales live in these waters today, that dipped to just 39 back in 2011, a decline that the Spanish conservation organisation CIRCE found was driven by a crash in bluefin tuna stocks. In 2010, international regulators slashed the annual catch that was permitted in the Mediterranean Sea. And, as the bluefin gradually recovered, so did the killer whales.

Their survival remains precarious. This specific population of orcas is listed as critically endangered and protected by law. But the ongoing conservation crisis does not explain why some of them suddenly started to behave so bizarrely and apparently aggressively around boats.

“I just didn’t believe it at all at first,” says Dr Ruth Esteban, a softly spoken marine scientist who chooses her words carefully, not keen to speculate about something as multi-faceted and complex as orca behaviour.

Ruth now works at the Madeira Whale Museum, but she studied this population of orcas for six years - they were the subject of her PhD.

“These killer whales are always curious around boats, they will approach them,” she tells me. “But touching them and causing damage? I just thought people were scared and were misinterpreting what was happening.”

But the reports kept coming.

In July, a sailing vessel had to be towed back to shore after a group of orcas repeatedly hit and damaged its rudder.

In August, a French-flagged vessel radioed the coastguard to say it was “under attack” from killer whales.

Later that same day, a Spanish naval yacht, Mirfak, lost part of its rudder after an encounter with orcas. A video of that incident showed the crew trying to outrun the animals, which appeared to pursue the boat.

In September, a man sailing his boat home to Scotland from Spain suddenly had the wheel spun out of his hands. A killer whale broke the surface at the side of the boat and he says that for 45 minutes, the animals bashed and chewed at the rudder, spinning the boat around.

“It’s getting worse and worse,” says Dr Renaud de Stephanis, another biologist involved in the investigation.

Renaud and Ruth used to work together on orca research; Renaud has been studying this population of killer whales since the 1990s. Through his conservation research organisation, CIRCE, he carried out work that helped the animals garner their officially protected status.

The two scientists are now part of a group carrying out an informal investigation into this strange, potentially dangerous behaviour.

Identifying the culprits

In September, the researchers started gathering evidence. They compared footage of the incidents to a catalogue of images captured and used by CIRCE to identify the animals. Orcas each have a uniquely shaped pale grey saddle patch behind their dorsal fin, which from the surface serves as a killer whale “fingerprint”.

This photo and video line-up showed that three individuals were involved in most of the incidents: juvenile males named in the official orca record as black Gladis, white Gladis and grey Gladis.

Killer whales live, hunt and move in very closely connected family pods: tightly knit, matriarch-led groups that - in some populations - have even been shown to have their own pod-specific dialects.

Families generally stick closely together, with long-lived grandmothers helping to raise young and to teach youngsters to hunt. Males though will wander off, mixing and mating among other pods. So far, the researchers have not worked out which family “the three Gladises” belong to.

The scientists published their conclusions about the identity of the culprits, and immediately there were news reports of the “rogue pod” and the marauding “teenagers”. The media coverage became stranger - and a little darker - when the scientists also revealed that Gladis white had quite a severe injury on his head: a gash that appeared to have been caused by a boat, possibly by a propeller.

This revelation caused the headlines to kick up an anthropomorphic notch: killer whales were “orchestrating revenge attacks”, said the New York Post. The UK’s Sun newspaper reported that a “rogue pod” was attacking boats “in REVENGE”.

On social media, amid gifs and jokes about the ocean fighting back, there were comments suggesting people on their yachts should “stay in their mansions” and that the orcas had been enlisted in a “fight against yacht owners”.

Ruth does not give much credence to the idea of vengeful orcas.

“The thing is - we don’t know what came first, the injury or the first incident with a boat.”

But there is one conclusion the scientists have confidently drawn from their investigation and from their years of observing these killer whales: they were playing.

A dangerous game

“They always seem to go for the rudder, and I think that’s because it’s a mobile part of the vessel,” Ruth explains. “In some cases they can move the whole boat with it. We see, in some of the videos, the sailing boat turning almost 180 degrees.

“If they see that they have the power to move something really big, maybe that’s really impressive for them.”

The investigation’s conclusions, the official advice for boats about how to avoid these potentially dangerous interactions - even the news stories - hinge on understanding what drives that animals’ behaviour.

So can any scientist, documentary-maker or sailor understand the mind of such a complex and intelligent marine predator?

Many have tried. While orcas were historically hunted and viewed by fishing communities as dangerous pests, the 1960s saw the beginning of what was arguably an equally dangerous fascination with the animals.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, orcas were captured for display in marine parks and, to the delight of thousands of spectators, to perform tricks with a trainer.

Conservationists campaigned against orca captivity for decades. But one killer whale, a large male called Tilikum who spent most of his life at SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida, brought the issue global headlines when he was involved in the deaths of three people.

The 2013 movie Blackfish made the case that Tilikum suffered mental trauma because of life in captivity, and that drove him to attack people.

Life alone in a concrete pool certainly bears little to no resemblance to the natural existence of a wild orca.

The animals live, migrate and socialise in closely connected family groups that have developed different hunting techniques and modes of communication. Some populations will only eat fish, preferring one particular type. Others will work together to hunt other, sometimes much larger, whales.

When the killer whales off the Spanish coast are chasing tuna, they can pursue them until the fish are exhausted. Researchers have observed some orcas appearing to “celebrate” after a kill.

“I’ve seen them hunting,” says Renaud. “When they hunt, you don’t hear or see them. They are stealthy, they sneak up on their prey. I’ve seen them attacking sperm whales - that’s aggressive.

“But these guys, they are playing,” he says of the recent encounters between orcas and boats.

There are no recorded accounts of an orca in the wild killing a human. But when killer whales play, it can be frightening.

“They can weigh 4-5 tonnes and when they play they really play,” says Renaud.

Other species can be targets of their apparent boisterousness. There are published accounts of the animals smacking seabirds with their flippers and repeatedly catching and releasing them in their mouths.

As top predators, aggression, dominance and shows of strength are likely to be key elements of any formative “play”. And for some of the most social animals on Earth, Dr Michael Weiss from the University of Exeter and the Center for Whale Research says, “when they play together, it could be building important social bonds”.

But for David, the skipper who encountered the killer whales, the word “play” sits uncomfortably with what he felt that evening.

“I just find it weird. The force that we experienced, it must have hurt them,” he says.

The mind of a killer whale

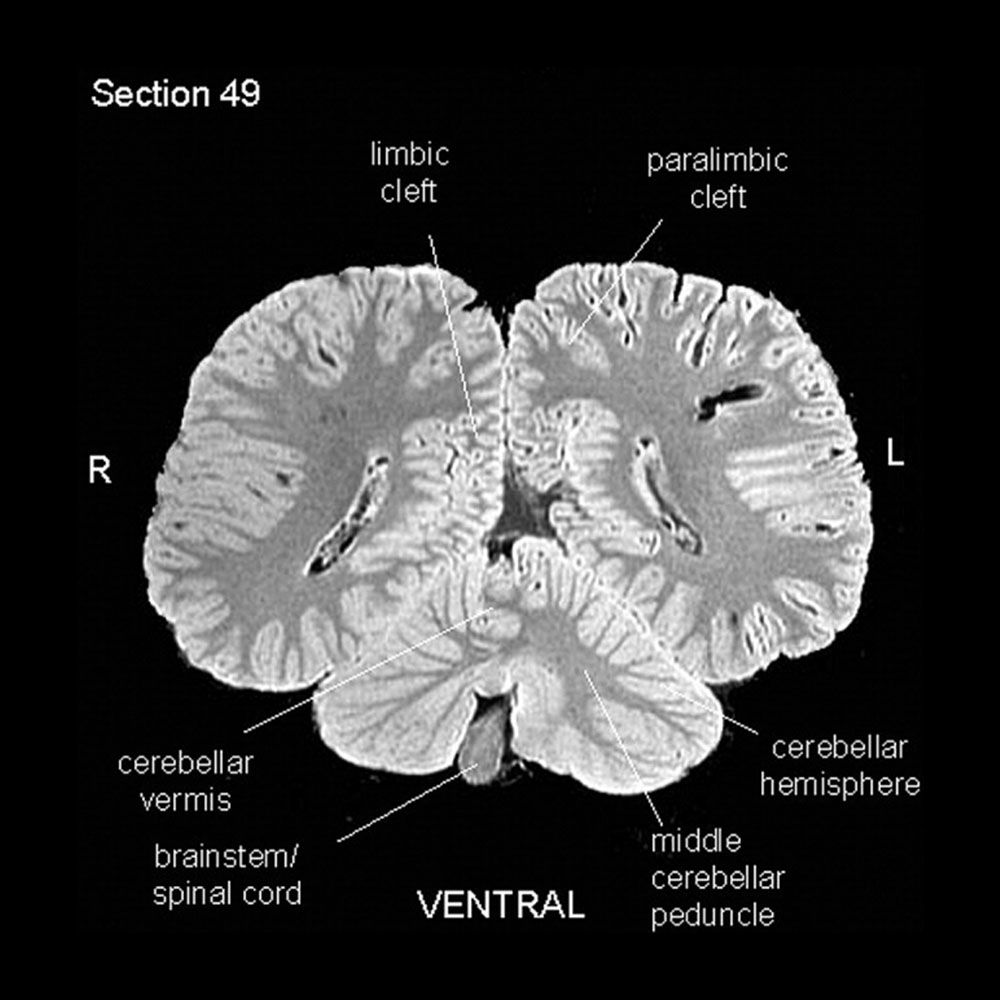

Neuroscientist Lori Marino, president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, is one of the few people to have seen inside the brain of a killer whale. She and her colleagues scanned the brain of a deceased captive orca for a study back in 2004.

“Parts of their brains - like the limbic system that you can think of as the emotional processor - they share with us,” she explains.

The Anatomical Record

The Anatomical Record

So orca behaviour that looks like anger, grief or joy is “probably exactly what they’re experiencing”.

Lori thinks we set ourselves up to misunderstand the species entirely by trying to lump their behaviour into simple categories like good or bad, aggressive or playful. “We make them into caricatures,” she says.

But there is a bigger reason for Ruth, Renaud and the team to try to adjust the language associated with these incidents.

“It was really scary for the people, I can understand that,” says Ruth. “But we don’t want to call it an attack. We call it an interaction.”

Ruth says the language used in news stories and social media posts - even by the coastguard - has been adversarial and loaded. She and the other researchers worry that these descriptions could be a step in a slippery journey towards persecution of critically endangered orcas.

Renaud, though, does admit being frustrated and genuinely worried by the orcas’ behaviour.

“From what I’m seeing, it’s mainly two of those guys [the Gladises] in particular that are just going crazy,” he says. “They just play, play and play. And the game is getting worse and worse.”

Renaud has seen signs of concerning behaviour whilst out on his own boat. Last year, a juvenile that he thinks is probably one of the same animals repeatedly chased his small boat with its face pushed up to the propeller of its outboard motor.

“They love it. And don’t know why,” he sighs. It just seems to be something they really like and that’s it.”

No human has been hurt in any of these incidents, and on the advice of the scientists, the coastguard has modified its language.

Despite this, some more recent behaviour is causing scientists genuine concern.

Recently, killer whales - assumed to be the Gladises - rammed into two fishing boats off the Portuguese coast.

Renaud on his research boat

Renaud worries that this could be a tipping point that could bring the animals into direct conflict with the fishermen, who may see their livelihoods as well as their safety on the line.

It is a situation playing out around the world. Predators including leopards, tigers and wolves are embroiled in conflicts with humans that are putting their survival in question.

Experts who study some of the most intractable human-wildlife conflicts in the world, where people may feel their lives are threatened by the proximity of large predators and that their only option is to kill them, have pointed to the role of “provocative language” in fuelling these situations.

Michael thinks there is something fundamental about our mentality around big predators.

“If they start behaving in a way we don’t like, then they’re mean, aggressive and evil,” he says. “We would be wrong to impose our sense of right and wrong on any other animal, let alone one with its own developed sense of culture.”

Lori says humans cannot even be expected to imagine how killer whales experience the world. They don’t just see the world, they hear it, echolocating and building a picture of their world based on a stream of visual and acoustic information that is all processed at the same time.

“And their ability to process information is orders of magnitude faster than ours,” she says. “If you look at how they respond to one another when they’re in a pod or a group - there’s a seamlessness to their interaction.”

In other words, they can be in sync in ways that our own brains are not wired to fathom.

Solving the mystery

However we describe it, and however human-centric our judgement, this nudging, biting and ramming of boats is new, potentially dangerous behaviour - both for people on boats and for the killer whales. It led the Portuguese coastguard to ban small sailing vessels from a stretch of sea where some of the incidents had been reported.

The biological puzzle of why this is happening remains an important one to solve.

While Renaud still rejects the idea of vengeful orcas - or even that the killer whales want to damage the boats at all - he cites decades of research when he suggests this could be part of a cultural shift that is actually helping the animals to survive.

Back in the mid-1990s, Renaud and his colleagues noticed that one of these orca pods had started to steal tuna from tuna boats, eating the bluefin from the end of longlines that trail in the water. Since killer whales learn from each other, the young animals in that pod learned the same trick.

The pod that “invented” taking bluefin tuna from the fishing lines has increased in number. And the number of “thefts” from the boats has also gone up.

“I don’t have the evidence yet,” he says, “but I would put my hand in the fire and say that this is the pod that the Gladises have come from.”

It is very likely that overfishing was a driver for these culturally conservative killer whales to develop a whole new predatory culture: seeking out lines to take fish from.

But has our overfishing pushed the younger orcas towards playing with boats? Have they seen mothers and grandmothers taking tuna from long lines and put their own adolescent spin on that family tradition?

“They’re young males, they’re going to be rambunctious,” says Lori. “There could be an element of play, there could be an element of aggression - of trying to prove themselves.”

But to say that they are just cruel and calculating or that they are just rambunctious and playful, she adds, does them a disservice.

“The real truth is not either one of those things. They’re capable of cruelty, they’re capable of kindness, they’re capable of all kinds of things just like humans.

“We can’t characterise them in one dimension. That’s an important lesson to learn.”

Credits

Writer: Victoria Gill

Editor and Producer: James Percy

Graphics: Gerry Fletcher, Rafael Fernández/Turmares Tarifa

Photography: CIRCE/Renaud de Stephanis

Additional images: Alamy, The Anatomical Record, David Smith

Video: Halcyon Yachts

Long Reads Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Published: November 2020

More Long Reads

The fight for Dragon Island

The death of the Full Moon Party