Hurricanes

Inside the deadly storms

"You get a sinking feeling in your gut, knowing lives will be changed."

That is how Heather Holbach, of the Hurricane Research Division in the US, describes the experience of flying directly into a category five hurricane before it reaches land.

"You're experiencing the strength and ferocity of Mother Nature and know it's heading towards people."

Reconnaissance missions like this are just one way that scientists and forecasters try to shed light on these monstrous storms, as they grow in size and move ever closer to causing destruction.

So let us take you on a similar journey - all the way from where a hurricane is born to where it dies.

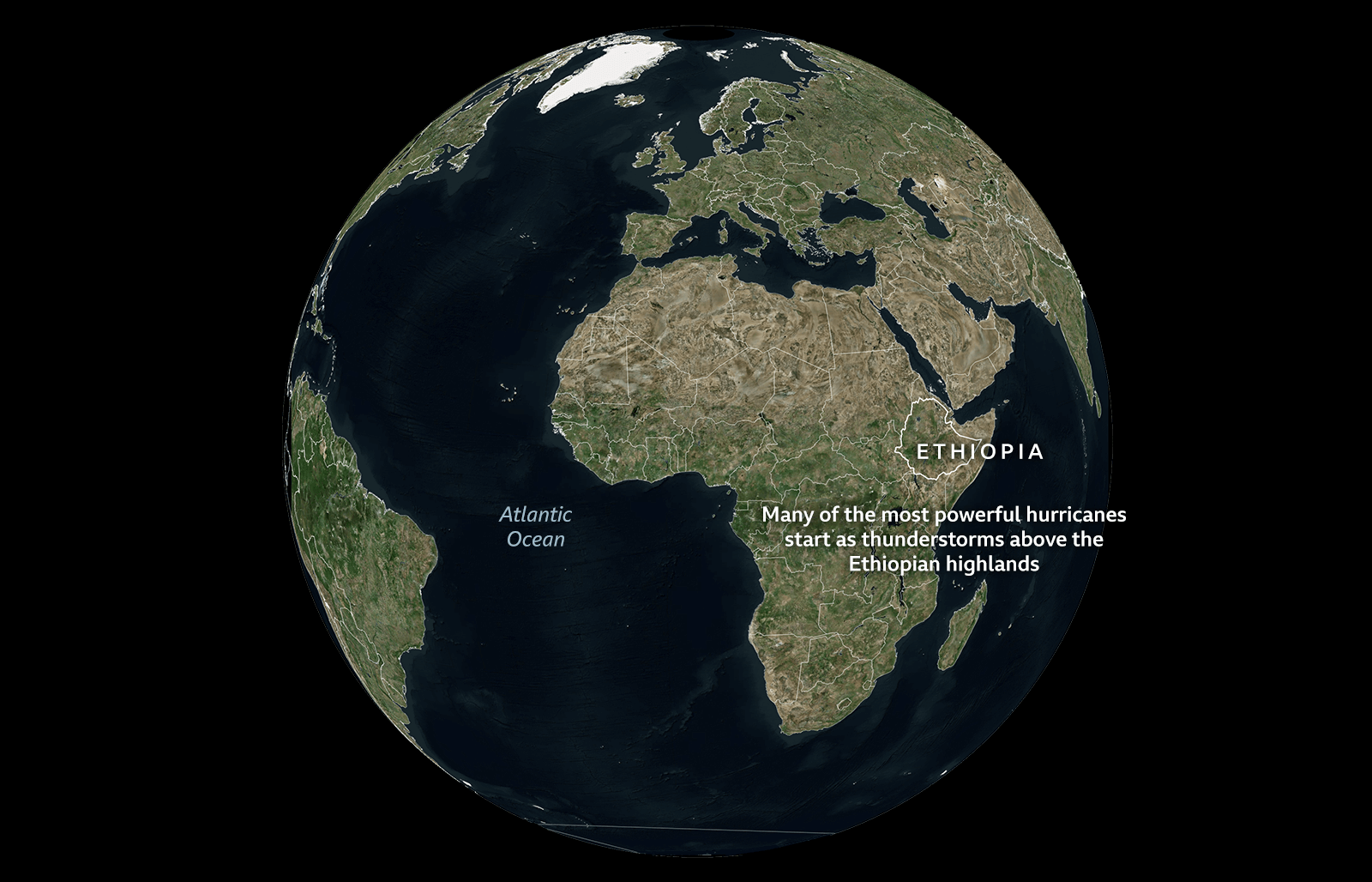

We start thousands of miles away from the Americas - over the African continent.

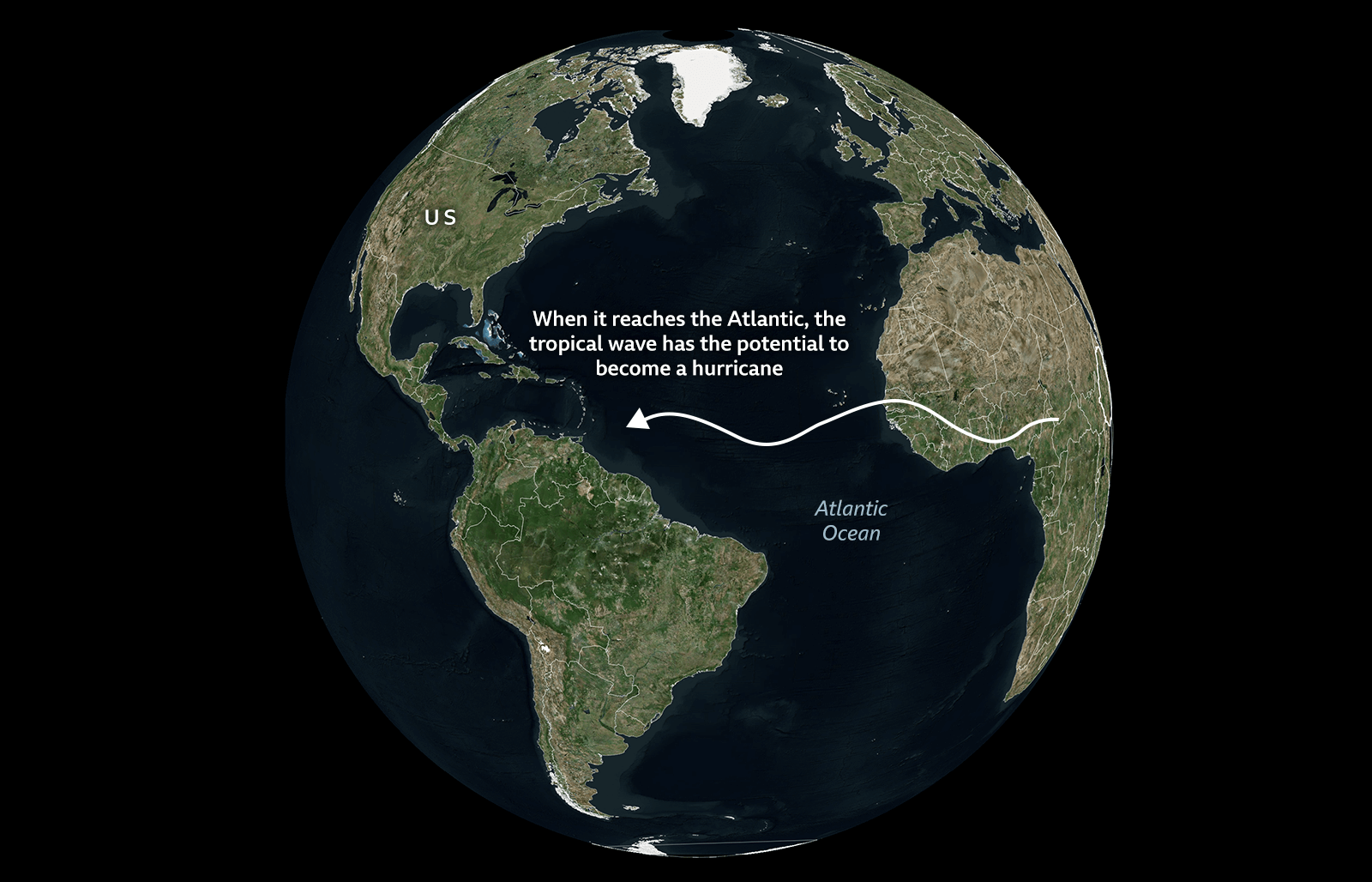

But for this to happen, it needs the right conditions: a concentration of rain clouds and high humidity over a warm ocean.

Sucking in energy from warm tropical surface waters of at least 27C (80F) - the fuel source for hurricane growth - the storm intensifies and starts to spin due to a phenomenon known as Coriolis force, a product of our planet's rotation.

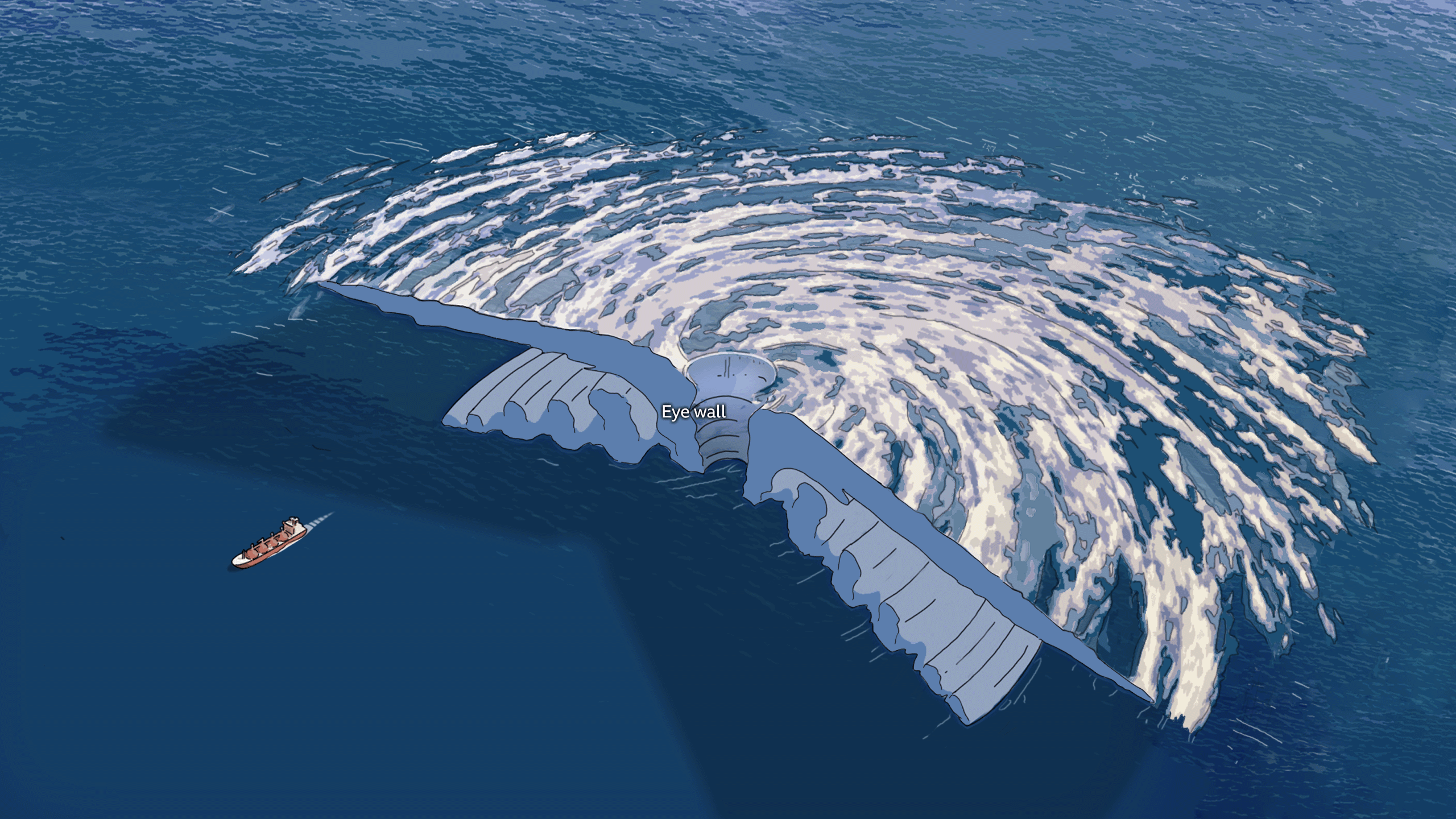

The centre of the storm is marked by the eye. Typically 20 to 40 miles (32 to 64 km) wide, this represents an oasis of calm within the maelstrom.

But the swirling winds of the eye wall that surrounds it are at their strongest and most destructive.

Spiralling around the middle are the outer rain bands. These lines of heavy rain can extend hundreds of miles from the hurricane's centre, but the winds become lighter as you travel further from the storm's core.

Once peak sustained wind speeds hit 74mph (119km/h), the tropical storm is officially a hurricane. Above 111mph (178km/h), it becomes a major hurricane.

Skirting the coast of South America, most Atlantic hurricanes pass across the Caribbean before approaching the US, Mexico and Central America.

Hurricane hunters

Flying into the heart of a powerful hurricane gives you some idea of what it's like to be a feather being tossed through the air, says Dr Jason Dunion, a meteorologist at the University of Miami.

For more than 25 years, he has flown on specially equipped aircraft known as "hurricane hunters" to study the winds in the most dangerous area of a storm – the eyewall.

"Mother nature puts the calmest part of a hurricane right next to the most intense part," says Dr Dunion. The eyewall winds can hurl the aircraft around so much that those inside experience strong g-forces.

"Then you pop out into the eye, and it becomes completely calm," he explains.

The view from a plane in the middle of a hurricane is formidable - you are surrounded by an immense wall of cloud sloping upwards and outwards.

"We call it a 'stadium effect' as it almost looks like you're at Wembley or a football game in the United States. You feel very tiny," says Dr Dunion.

These missions can be treacherous, but they provide information you can't get from a satellite.

Scientists gather data about the three-dimensional pattern of winds, known as the wind field. This helps them predict the strength of the storm surge that will hit land.

The aircraft release remote sensors, known as dropsondes, with mini parachutes to record wind speeds, temperature, air pressure and humidity all the way down to the wave-tossed ocean surface.

Other instruments on board help to calculate surface wind speed while radar provides a view of the storm's entire structure, including how far and high hurricane strength winds extend, and where the heaviest rainfall is located.

This helps forecasters work out which storms might intensify rapidly and where they might cause the most damage.

"We need to be better at predicting rapid intensity cases," warns Dr Jonathan Zawislak, a meteorologist and flight director at Noaa's Aircraft Operations Center.

"I worry about a coastline where you go to bed prepared for a category one and you wake up to a major category three."

Landfall

As soon as the hurricane hits land, it no longer has access to warm waters. Starved of its fuel source, it begins to weaken.

But even as it does so, it can unleash destruction. There are three main hazards.

Strong winds

With sustained winds of 165mph (266km/h) when it made landfall - some of the strongest winds to hit the US mainland - Hurricane Andrew in 1992 destroyed more than 25,000 homes and damaged at least 100,000 in southeast Florida alone.

Torrential rain

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey broke all sorts of records, dropping more than 1.5m (60 in) of rainfall over southeast Texas, causing catastrophic flooding.

Storm surges

Often the most dangerous of all hurricane hazards, these are the short-term increases to sea level caused by a storm, frequently leading to coastal flooding. High winds 'push' seawater towards the coast and low pressure at the centre of the storm 'pulls' the water level up.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the southeast Louisiana and Mississippi coastlines in 2005, it brought storm surges of around 3-8m (10-28ft) above the normal tide, leading to hundreds of deaths.

Climate change and hurricanes

Climate change is not thought to bring more storms, but hotter oceans and warmer air can supercharge the strongest hurricanes, bringing even higher wind speeds and heavier rainfall.

And remember, climate change is already pushing up sea levels. That makes even the smallest additional storm surge a potential disaster.

Aside from fighting climate change by using less fossil fuels, humans have no control over the strength of hurricanes, but people, and in particular, governments, can help to make them less deadly.

In 2017, Hurricane María killed around 3,000 people in Puerto Rico.

Research by Virginia Tech showed that differences in hurricane strength and flood depth across the island didn't dictate how much damage an area suffered - human vulnerability was even more important. Poorer communities were more likely to live in more flood-prone areas with weaker building standards, for example.

That's why scientists say there is no such thing as a truly 'natural' disaster - and in a warming world, being better prepared for these storms will only become more important.

"Are you in an area that could be inundated by storm surge? How well is your home built? Are you on a barrier island which could become cut off?"

These are questions Dr Holbach advises all those living in a hurricane's potential path to consider if they can.

"Know what you’re going to do if you’re without power for a week or more," she says. "Always have a plan."

Credits

Writers: India Bourke, Mark Poynting, Ben Rich

Designers: Gerry Fletcher, Katherine Gaynor

Producers: Dominic Bailey, Paul Sargeant

Editors: Richard Gray, Greg Brosnan

Video and photography: Nasa, Noaa, Getty Images, Reuters