Lessons from the lockdown

What happens when everyday life suddenly changes?

By Sean Coughlan

Additional reporting: Claudia La Via in Milan, and Sofia Bettiza

“I don’t think it’s really hit me yet,” says Maria Vittoria Falchetti, who works for her family’s firm in the northern Italian town of Codogno, in the epicentre of the country’s brutal coronavirus epidemic.

Her father Umberto, founder of a car components business, has become one of the casualties. The 86-year-old died in hospital from the virus, with the isolation rules not allowing his family to be with him.

“I’m still in quarantine and working from home. But I dread the day when I go back to the office.

“My office is next to his. He kept this little purse in his drawer and I used to hear every time he took out some coins. I knew he was going to get a coffee from the machine,” she says.

“I will miss that noise.”

The lack of noise can be deafening. Quiet streets, empty public transport, bars and restaurants that have closed, self-isolating families and locked-down cities have become part of the strange days of this Covid-19 pandemic.

Private grief such as Maria Falchetti’s comes as public life seems to be falling apart.

Maria Vittoria Falchetti

If the world is holding its breath to see what happens next, Codogno, a small town in Lombardy, is a microcosm of how the virus can overrun a community - and how that community can fight back.

One month ago, when coronavirus was first detected in the town, even the idea of locked-down towns guarded by police checkpoints would have seemed like something from a paranoid disaster movie.

Two days after the outbreak was confirmed in Codogno, everyday, modern, globalised 21st-Century life in the town had come to a halt. From being a 1,000-year-old town with cafes and old churches, it became the place where “patient one” - the person at the start of a chain of contagion - was infected.

People accustomed to going wherever they wanted found themselves ordered to stay behind a new frontier. They had become mask-wearing residents of a quarantined “red zone”, a firewall to stop the disease.

One of the most surprising things was how quickly people adapted, says Roberto Cighetti, a science teacher in the town.

“The priorities become clear - food, health, family. That’s it. You adapt in a moment,” he says.

If Italy’s journey into Covid-19 is a few weeks in front of the UK’s, there are clues about the road ahead.

Cighetti says panic buying was one of the first social symptoms of the epidemic.

“It’s difficult to behave well under pressure,” he says. What stopped people hoarding food was when the supermarkets demonstrated there was no shortage - by constantly and visibly re-stocking shops.

Once people were confident there were no problems with the food supply, the “panicking behaviour” stopped.

The next social challenge was an eruption of fake news. WhatsApp groups were pinging with the spread of hoaxes, false cures and conspiracy theories.

“There is an instinct to spread news without verifying it, so there were rumours that were totally fake,” says the science teacher. “They created anxiety and panic and lowered the level of trust.”

Cighetti was so worried that misinformation was disrupting authentic public health advice that he took to social media with other scientists to try to counter the fake facts.

Local people have suffered from an “epidemic of information”, he says, both useful and fake.

That might be a by-product of another unwanted piece of history about this outbreak. As epidemiologist Professor David Heymann says, this is the first time that we’re within a pandemic that “we can follow in real-time”.

There was also the social distancing to get used to - and that could have its own psychological isolation, says Cighetti. “The distance translates into an emotional distance.”

The coronavirus has shown how vulnerable and fragile our interconnected world can suddenly become. But the same modern communications are keeping people together.

There have been remarkable online eruptions of solidarity. Italy has had its own instant festivals of singing and music from balconies, with an opera singer delivering Puccini over the rooftops of Florence like some kind of epic soundtrack.

Italians sing from their windows to boost morale

Italians have also taken to raising an online glass to the friends they can’t see in person. The “aperitivo” after-work drink has switched to Instagram.

In Paris, people stuck inside their homes are opening their windows for synchronised night-time rounds of applause for medical workers. This clapping and cheering, echoing around the empty streets, comes from thousands of people who are separated and together at the same time.

In the UK, social media is being used to prepare for the storm ahead, sharing ideas to help the elderly or isolated. A Covid-19 Mutual Aid group is supporting hundreds of local efforts and neighbours have been signing up to WhatsApp groups to offer assistance.

If the Italian experience is any guide, there will be mood changes in public responses to the coronavirus, with the seriousness not necessarily evident at first.

At the start of Codogno’s strange new life of the lock down, Cighetti says it felt like a “boring holiday”. The schools had closed, the bars and restaurants had shut, streets were empty, no-one was able to travel.

There were even positive sides.

In the red zone, apart from those who were ill or self-isolating, people could move within the town and the enforced break meant “families spending more time together, walking, cycling, walking the dog, baking cakes,” says Cighetti.

Pupils missed being at school and the science teacher says that when they had online lessons children actually seemed more engaged than usual, appreciating the return of normality.

Roberto Cighetti

But Covid-19 was stalking the town - and Cighetti says the rise in deaths and illnesses meant the atmosphere changed from complaining about disruptions to work and cancelled trips to something much darker.

The isolation zones made grieving even more traumatic, with families unable to reach the funerals of even their closest relatives. A son couldn’t get to the funeral of a mother.

By 13 March there had been 34 deaths in a town of only 16,000 people.

There have been economic shockwaves too, rippling out from fears for restaurants in Codogno through to multi-nationals and tourist industries across northern Italy and beyond. According to the International Labour Organization the virus will destroy 25 million jobs worldwide.

In the globalised supply chain, the disruption to local businesses can have international implications. The firm founded by Maria Vittoria Falchetti’s father produces electronics components for the car industry - and its shutdown threatened a domino effect, until an exception was made to allow production to resume.

The Lombardy lockdown, seen as a draconian measure by international standards when it was introduced, appears to have succeeded in significantly reducing the number of new cases in Codogno. There is some light in sight.

Local mayor Francesco Passerini said the town had given a “virtuous” example to the rest of the country.

“It’s a war. But we have every possibility of winning. Unlike with our grandfathers who went physically into battle for our freedom, we are being required to show responsibility - responsibility and calm,” said the mayor.

Quarantined

Radio Red Zone must be Europe’s only disease-fighting radio station. It is broadcasting from behind enemy lines in the battle against the virus, serving an audience in Codogno trapped inside the quarantine zone that gave the station its name.

Its 83-year-old presenter, Pino Pagani, is there to reassure his neighbours and help them not to be panicked by the virus, even though he lost three of his friends in one week to the epidemic.

“The worst thing is the fear. We are afraid of one another. The other day I met a person I knew who was crossing the street. I gave him a pat on the shoulder and he shied away frightened,” he says.

Pino Pagani

The Lombardy town of 16,000 people has found itself as the unexpected frontline of a pandemic. When they sent home their schoolchildren it was a local problem. A month later, half the world’s entire school population - about 850 million children - are out of school, according to Unesco, including now in the UK.

The radio presenter says the station’s phone-ins and information lines are there to “keep people company” while ordinary life has been suspended. There are parents having to keep children occupied, people worried about their jobs and looking after their older relatives.

“They ask for advice, they want to hear our voices. They think that if we are still going, everything will be fine. So they keep on calling us,” says Pagani.

He gives the example of a listener concerned about having a high temperature, but who didn’t have a thermometer to check and didn’t want to go outside.

“So we passed the call to the civil protection service and they immediately delivered a thermometer to her home. She was so relieved.

“It’s also a way to solve very practical problems. We tell them which bakeries are open, what time the supermarkets close. People in need can rely on us to find help.”

Among the biggest worries are about the elderly, in a country with one of Europe’s oldest populations.

“My sons worry about me,” says Pagani, a widower. But he refuses to be anxious for himself.

“My family don’t want me to leave the house. Whenever I go out, such as to present the show, my sons block the door and keep telling me, ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that’.”

But he remains undeterred.

“I’ve lived my life and endured a lot of hard times. I take care when I go outside, of course, but life must go on,” says the radio presenter.

But these are strange times.

One of those friends who died was a co-presenter on the radio show.

“He was a close friend of mine, three months younger than me. We’ve known each other since kindergarten and we grew up together. The last time I spoke to him, he said he couldn’t come in because he wasn’t feeling well.

“He said he had a temperature and he was worried about infecting us. I told him not to worry. He died last week and we couldn’t even go to the funeral because of the ban on public gatherings.

“So we paid a tribute to him on the airwaves.”

Wuhan of Italy

They’re unlikely to want to put it on tourist posters, but Codogno has acquired the label the “Wuhan of Italy”, linking it to the Chinese city that saw the first cases of Covid-19 at the end of December 2019.

Codogno is the first point in the detective story of how a virus from China reached Italy and began Europe’s most deadly outbreak.

“You remember it clearly when you get shocking news,” says Cighetti.

The science teacher was making an early morning wake-up cup of coffee when the news appeared on his mobile phone. The virus which had closed cities in China had appeared, as if from nowhere, on his doorstep.

“It didn’t seem real,” he says.

The attention of the world’s virus investigators swung to Codogno as a 38-year-old man had tested positive. The town was being described as the “ground zero” of the coronavirus.

What made it even more alarming, says radio presenter Pagani, was that the first person to have coronavirus was “a real sporty type and healthy” and he had fallen seriously ill.

The man, Mattia, is a manager for the Anglo-Dutch firm Unilever, a project leader for cleaning products. He had previously taken a course in hygiene at one of the firm’s UK bases.

“Patient one”, as he became known, is a keen sportsman who belonged to a running club and socialised in the bars and restaurants. He worked for a global business with offices and production centres around the world.

He is now recovering, but a chain of infections had followed him, among his family, friends, other people in the town and health workers and patients. While these circles widened, the urgent hunt was on to make a link with the outbreak in Wuhan.

Italy had already stopped flights from China, but it hadn’t stopped the case in Codogno. An initial suspicion that Mattia had been infected from a friend who had been to China soon proved to be a false lead. His employers also told the BBC that he had not visited China.

So how had Covid-19 reached Codogno?

Professor Paul Kellam of Imperial College London is an expert on the genetics of viruses. His team delivered the genome analysis that helped to tackle a previous coronavirus outbreak, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, known as Mers.

Each time a coronavirus moves from one person to the next, there is a slight genetic mutation, says Prof Kellam, allowing researchers to map its “family tree”.

So when a version of the virus is analysed from any new location, it is possible to see how it compares with samples from the original outbreak in Wuhan, or its relationship to other offshoots of the virus in other countries.

Researchers in Milan reported that the version of the coronavirus in Lombardy matched an outbreak in Germany, centred on a businessman from Munich who had met a woman from Shanghai carrying the virus.

This would mean that while the Italian authorities were closing the air routes from China, the virus could have already arrived from Germany.

There were questions about this interpretation - with the argument that even if the German and Italian versions of the virus were similar, they could both still independently have been the result of contacts with another separate source.

Either way, there was another intriguing finding from the genetic analysis - that the virus had been circulating for several weeks before it was detected in Codogno.

While “patient one” was being checked for any personal links to China, the coronavirus already had a head start and would have been moving quietly in the population.

This is reflected in the observations of local people, including Pagani, who reported a number of unexplained and “quite weird” cases of a pneumonia-like illness before the first coronavirus was formally identified.

Prof Kellam takes the origins of Covid-19 back a stage further. Such viruses originate from animals, with bats the most likely starting point. In the cases of other coronaviruses, such as Mers and Sars, the virus went from bats to other animals, before infecting humans.

Even if there has been public shock at the impact of Covid-19, he says scientists have been “highly aware” of the potential for more viruses to cross over from animals. In the case of bats, it’s likely to be through droppings, saliva or urine.

In March 2019, virus experts published what seems remarkably prescient warning - that bat-borne coronaviruses “will re-emerge to cause the next disease outbreak. In this regard, China is a likely hotspot”.

“The challenge is to predict when and where, so that we can try our best to prevent such outbreaks.”

Perhaps more strikingly, the four scientists who wrote the paper were all based in the Institute of Virology in Wuhan.

But there is another dimension to this. Coronaviruses, first identified in 1968, require the overlap of human life with animals - and this becomes ever more frequent as wildlife habitats are destroyed and wild animals are brought into closer contact with humans.

This warning about the risk of infection from “human encroachment into natural spaces” isn’t a piece of environmental opportunism. It’s from the military technology agency of the US Department of Defense, which has been funding projects to tackle the threat of bat and other animal viruses.

Months before the Wuhan outbreak, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) had highlighted the risk of a pandemic to the US population from infectious diseases from animals.

It’s extraordinary to think that such a chain of events, with so much chaos and destruction, might have been caused by a single bat in China. While financial markets describe unpredictable disasters as “black swans”, the billions wiped off the value of shares could have started with a small bat.

On the front line

“Right now, we feel like we are in the trenches - and we are all scared,” says Paolo Miranda, an intensive care nurse in the only hospital in Cremona.

The hospital, about 28km (17 miles) from Codogno, is only treating patients with coronavirus and even then it can’t keep up with demand. A field hospital is being built outside, to add to the 600 patients already being looked after inside.

“Everyone is calling us heroes, but I don’t feel like one,” says Miranda.

Like many of his colleagues, he’s been working 12-hour shifts for the past month. “We are professionals, but we are getting exhausted.”

Paolo Miranda

Overwhelming demands are being placed on staff, as hospitals struggle with the scale of the pandemic. In the four weeks since the discovery of “patient one”, the number of cases in Italy has risen to over 41,000 cases and 3,405 deaths.

As of 17 March, three quarters of all the coronavirus deaths in Europe were in Italy.

In Lombardy alone, there were 319 deaths in a single day.

The experience of these Italian hospitals has been an important factor in the UK toughening up its own measures against the virus, after a report this week from the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis.

Inside a hospital in Italy

For those working on the frontline it has become a terrible new reality.

In the nine years he’s been a nurse, Paolo Miranda has seen many people die – he’s used to it. But what has struck him during this pandemic is seeing so many people die alone.

“When patients die in intensive care they are normally surrounded by their family. There is dignity in their death. And we are there to support them, it’s part of what we do.”

But with families and friends prohibited from coming to the hospital, to prevent the spread of the contagion, it means that these often elderly patients have no-one with them.

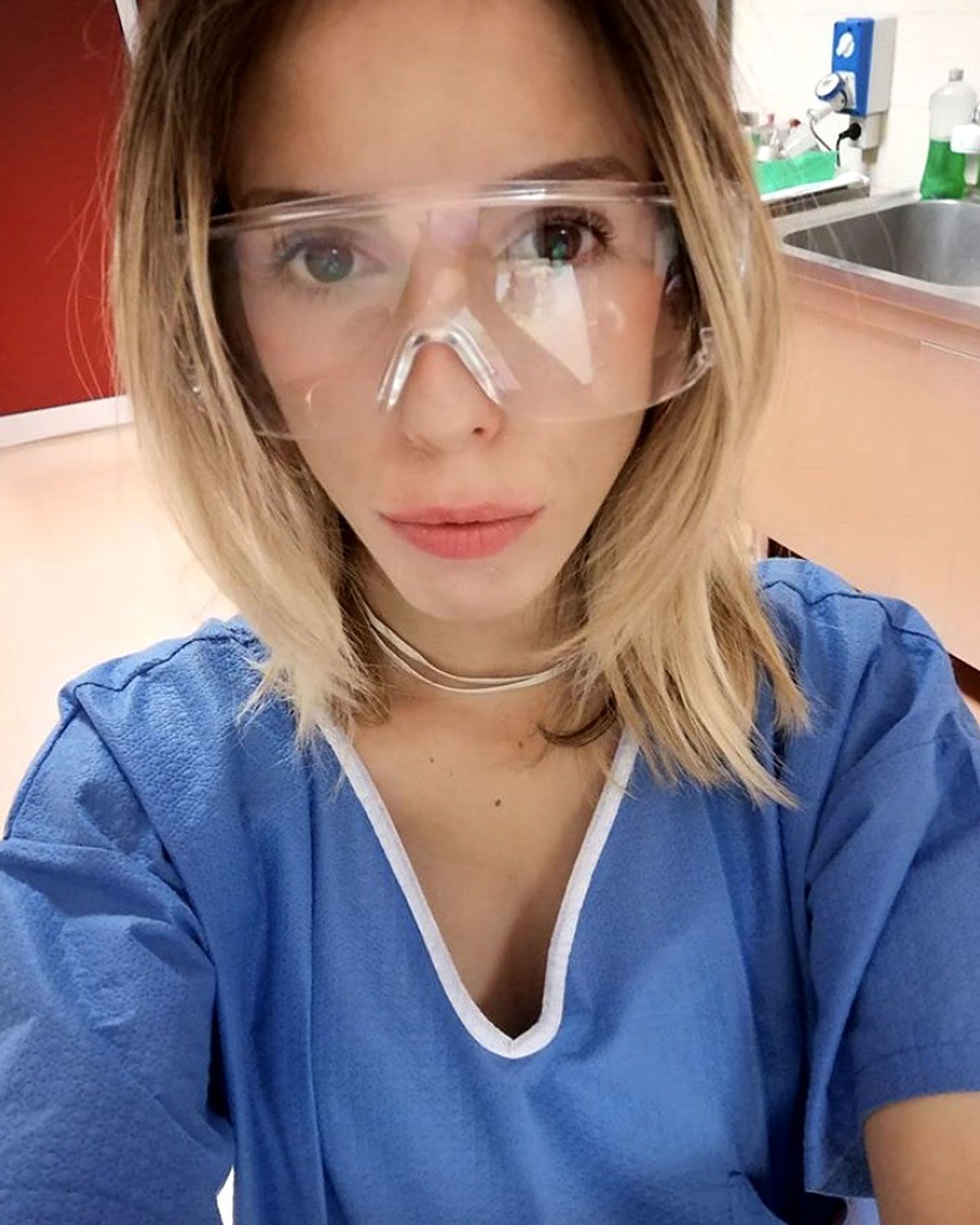

Anna, a 24-year-old healthcare worker in another hospital in Lombardy, says the separation from loved ones at the end is the “hardest thing”, with no-one “holding their hand or whispering something to them”.

Anna

It’s difficult for the staff in Cremona’s hospital to keep going - and they struggle to switch off.

“I’m shattered when I come back home at the end of my shift. But then I go to sleep, and I wake up several times during the night. Most of my colleagues do,” says Miranda.

He decided to document the bleak situation inside the intensive care unit by taking photographs. “I never want to forget what’s happening. It will become history.”

In his photos, he wants to show his colleagues’ strength – but also their fragility.

“The other day, out of the blue one of my colleagues started shouting and jumping up and down in the corridor. She’d got tested for coronavirus, and had just found out she didn’t have it. She is normally very composed, but she was terrified and couldn’t contain her relief. She’s only human.”

He says he is surviving on a mix of adrenaline and the support of his colleagues.

“At times, some of us crumble, we feel despair, we cry because we feel helpless when our patients are not improving.”

When that happens, other members of the team immediately step up to help. “Otherwise we’d lose our minds.”

The situation is starting to take its toll on health workers across the country.

“At some point we will have to choose who we can treat and who we cannot. This is the biggest concern,” says Martina, an intensive care nurse in a hospital in Massa Carrara in Tuscany.

“The situation is disturbing, on a physical and psychological level.”

Codogno method

The experience of Codogno in the past month has been to try to contain the spread of the virus by containing its people. It’s been called the “Codogno method”.

But in a democracy with individual freedoms, how far can you push people to comply? Even more stringent measures have been applied in China, but how would that work in a country such as the UK?

“Top-down public health measures don’t work if they don’t get buy-in from communities,” says Melissa Leach, director of the Institute of Development Studies, at the University of Sussex, who worked on tackling the Ebola epidemic.

You have to understand people’s “fears and anxieties”, she says, and at present the public mood is dominated by “uncertainty”.

She says there needs to be a “humanised” approach which recognises there are “questions of ethics, rights and justice” rather than “riding roughshod over people’s feelings”.

In Italy there have been strict instructions to limit movement, while the UK’s approach has been more about voluntary guidance.

“It’s strikingly distinct from other governments,” says former home secretary Charles Clarke, who in office was involved in contingency planning for disasters such as pandemics and terror attacks.

The key difference is the extent to which the UK government is steered by scientific advice, says Clarke, with the visual embodiment being that when the prime minister speaks he is flanked by his expert advisers.

“Politicians’ words are never going to reassure people. They think politicians have other motives,” says Clarke.

He backs the policy of sticking to the scientific evidence and says there will have been very detailed planning and rehearsal of each step taken, including the language of how it’s presented.

For instance, a phrase like “self-isolating” suggests a positive choice by people and not something imposed on them by government.

But for those in Lombardy whose families have already suffered, there are more immediate worries.

Maria Vittoria Falchetti is getting her family’s company, MTA, back up and running again - while mourning the loss of her father.

“Work is the only thing that keeps us alive at the moment, despite the fear and mourning,” she says, with production now resumed in Codogno and a factory in Shanghai. It’s another example of the connectivity that links even a small town with the global economy.

She says her father would have been proud of how the workforce in Codogno has “pitched in” to help.

Staff now stand apart from each other, they have their temperatures checked and are given gloves and the face masks that have become the hallmark of the pandemic.

It’s been a continuous story of the grimly unexpected, including the death of her father.

“He had a high fever and was having difficulty breathing. The ambulance took him to the hospital and we never saw him again. He died alone,” she says. “They didn’t allow us to visit him.”

Falchetti says she feels “scared and dazed” by what’s happened.

Even when “normality” comes back, she says, “nothing will be the same any more”.

Credits:

Author: Sean Coughlan

Additional reporting: Claudia La Via in Milan, and Sofia Bettiza

Images: Paolo Miranda, Getty Images, Alamy, Reuters, MTA

Graphics: Gerry Fletcher

Production: James Percy, Paul Kerley

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Published 20 March 2020