Wuhan: City of silence

Looking for answers in the place where coronavirus started

In a small room, in a village on the outskirts of Wuhan, an elderly woman is chanting quietly and tapping out time on a table. Opposite her, another woman is crying softly. In early February, her 44-year-old brother died from coronavirus, and she cannot forgive herself.

After the ceremony, Ms Wang - she doesn't want to use her full name - says that the shaman received a message from beyond the grave. Her brother, Wang Fei, had absolved her of any blame. “Feifei doesn't hold me responsible,” she says, referring to him by the name the family has used since childhood. “He was trying to comfort me and persuade me to accept his death.”

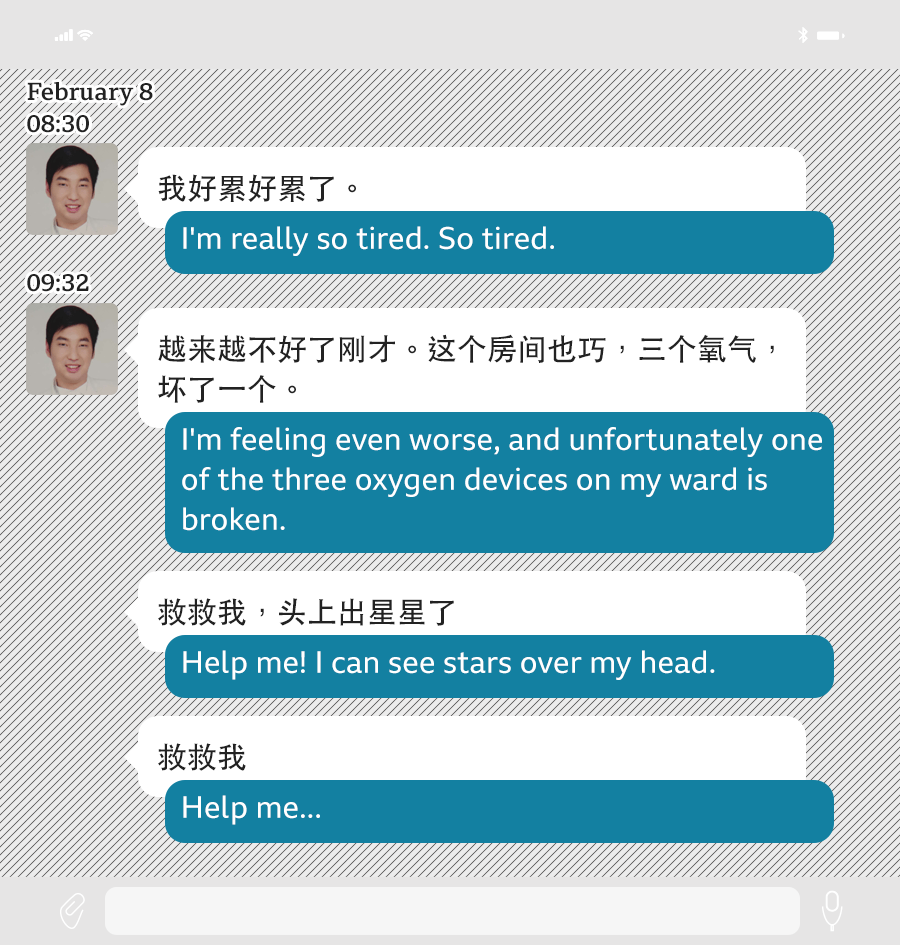

Her brother died on a Covid ward, unable to see visitors; his last days lived out in a series of desperate text messages.

“I feel so tired,” he wrote in one of them. “This disease has dragged on for too long.”

Ms Wang’s guilt is a product of one of the cruellest aspects of this global pandemic – the enforced isolation of sufferers from their families.

“I couldn’t go to the hospital to take care of him,” she tells me. “When I heard he’d died, I just couldn’t accept it. My family’s been broken into pieces.”

She wants answers about her brother’s treatment - whether he was given proper care, and whether more could have been done to save him.

But Ms Wang has been told by the police not to speak to the foreign media, and her choice to ignore that warning carries some risk.

Ms Wang sets fire to papers with prayers written on them in an offering to her brother

Ms Wang sets fire to papers with prayers written on them in an offering to her brother

One woman we arrange to interview arrives with plain-clothes policemen in pursuit. When she scrambles into our car, they block our way.

We meet another man in the darkness on the banks of Wuhan’s East Lake. He tells us he’s been visited twice by the police for speaking out about the death of his father.

For victims and journalists alike, asking questions about how and why the outbreak began in Wuhan, and whether it might have been better contained, is not easy. But at the epicentre of this global disaster, the need to ask questions is a necessity, not a choice.

The day in mid-January when Wang Fei began to feel unwell, China's official death toll stood at just three. Today, more than 11 million people have been infected worldwide, at least 500,000 have died - and the virus has forced the lockdown of entire economies.

It is here where the virus was first discovered and the first attempts made to contain it. And it is here, too, where the search for its origin must begin, leading to perhaps the biggest question of them all, and one now at the heart of an escalating propaganda war between Washington and Beijing.

Did the coronavirus – as most scientists think – come from nature, or might it have leaked from a lab?

The descent

Ms Wang says her brother, who worked as a driver, hardly ever left Wuhan. Over the course of his 44 years, the central Chinese city grew from a declining industrial backwater into a booming international business and transport hub. But if Wang Fei’s life coincided with Wuhan’s extraordinary revival, then his final days ran in parallel with its descent into disaster.

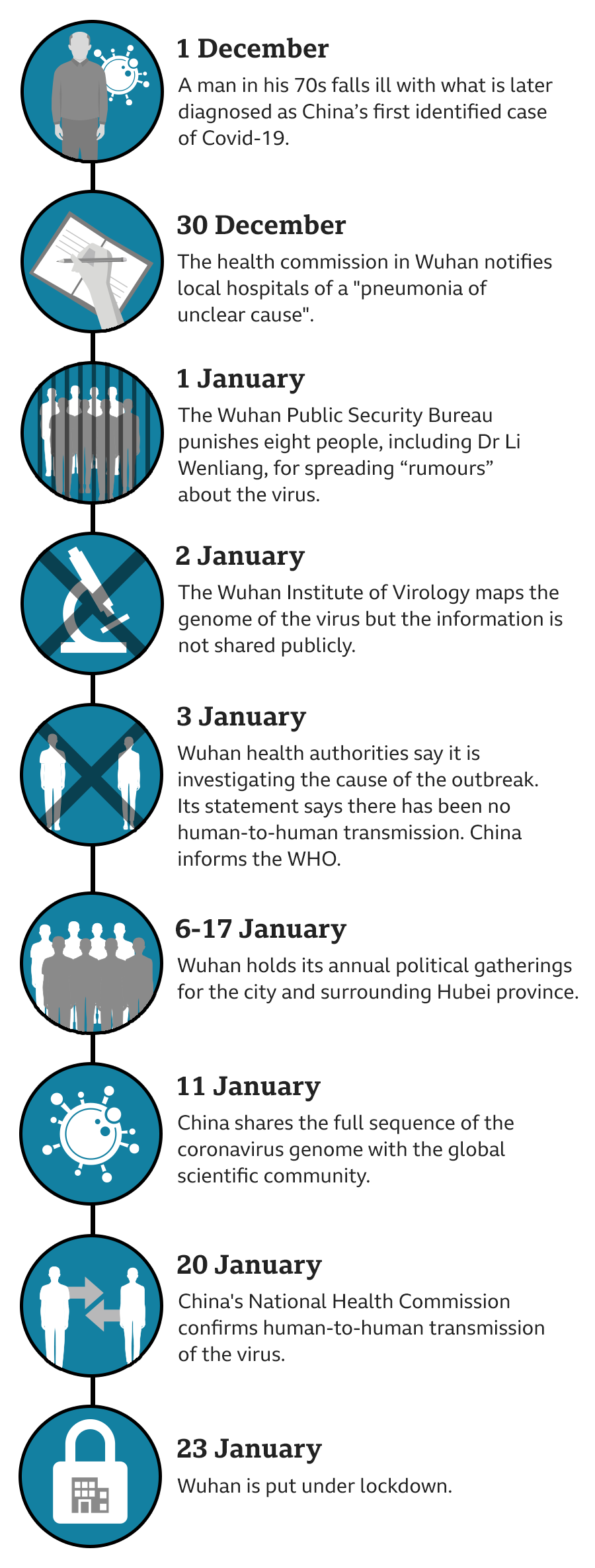

In early January, medics had begun to realise that the disease was highly infectious and were implementing their own hospital quarantine procedures.

But instead of alerting the public, the authorities were silencing health workers. Li Wenliang, a doctor who tried to warn colleagues to take precautions against infection, was reprimanded and made to sign a confession by the police.

On the weekend of 18 January, with the authorities still insisting the disease was not contagious, Wang Fei began to feel unwell. He went to hospital where he was given paracetamol for his fever and sent home. “They say there’s no human-to-human transmission, but the doctors are all wearing masks,” he told his sister.

She can repeat the exact wording of the official reassurances, even now. “At that time, I was telling him that it is 'controllable and preventable,'” she says. “Only when I look back, I realise the government really didn't give enough warning. Now I know what he really needed was proper medical help. That’s what makes me feel guilty.”

Mr Wang cancelled the family’s plans to celebrate the Chinese New Year holiday, which fell the following weekend.

Instead he spent his days joining long queues outside hospitals. But with too many patients and not enough beds, he would return home exhausted.

“He believed deeply that the country and government loved him,” Ms Wang says, “and that they would protect him.”

On 23 January, Wuhan was put into lockdown. It was the world’s first, and became one of the longest and strictest attempts to contain the spread of the virus. But it came too late to prevent an estimated five million people leaving the city in the run-up to the national holiday.

A few days later, his condition deteriorated and the family called for an ambulance. They were told there were more than 600 people ahead of them in the queue. Seven hours later he was finally admitted to hospital.

Mr Wang found himself in a health system that was now totally overwhelmed. He texted his sister, complaining about the difficulty of getting staff to attend to his basic needs - such as help with drinking water. He continued to get worse. On 7 February Dr Li Wenliang, the doctor censored by the police, died in the same hospital. Mr Wang's spirits sank even lower. “If even a doctor can't survive,” he told his sister by text, “what chance have I got?”

They are still silencing medics in Wuhan. Outside one hospital, we speak to a nurse who tells us about her experience on the front lines dealing with Covid-19 patients. Afterwards we exchange contact details and she cycles away. Two plain-clothes policemen, who have been watching us, emerge from the side of the street. They run alongside her with their hands on her handlebars, and bring her bike to a halt.

I can see them speaking sternly to her, but by the time I catch up with them, they’ve let her go. She calls a few minutes later and asks us to delete the interview. For her safety we have no choice but to agree.

The control of information, of course, has long been central to China’s system of government. In this case, it is central to the story.

Wuhan’s lockdown was successful in eventually bringing the city’s outbreak under control, but China faces allegations, including from the US government, that delay and cover-up in the early stages made a global crisis inevitable. In the early stages of any disease outbreak, even days can make a big difference to the speed and scale of the spread.

One study has suggested that if it had acted a week earlier, the number of cases in China could have been reduced by 66%. The authorities deny the allegations. They insist that, in the face of a previously unknown disease, their response was swift and point out that it has been commended by the World Health Organization.

The government is now comparing itself favourably to administrations in the West, even overtly mocking them for what it sees as a chaotic and confused response.

And it is silencing those who might challenge that narrative.

While the failings of democratic governments have been comprehensively exposed by a free press, there is no such scrutiny in China. This is a place where even trying to talk openly about your dead brother can bring you to the attention of the police.

We put in requests to interview parliamentary delegates, senior health officials, academics and doctors - more than 20 people. None of our requests were granted. We sent questions to China’s health commission and its foreign and science ministries about the release of public information in the early days of the crisis. They went unanswered too.

Spillover

Wang Fei lived a short walk from a large market that became an early focus of the unfolding story. Despite its name, the Huanan Seafood Market is known to have had some trade in wild mammals sold there as delicacies. It is now closed.

Initially, it was suspected to be ground zero for the outbreak, the place where the virus made the leap from animals to humans.

Sars-CoV-2 – as it has now been named - belongs to a family of coronaviruses named for their spikey or crown-like surfaces. A vast number of these viruses have been shown to be carried by bats.

Some of them are thought to have the potential to infect humans, either when passed directly from a bat, or after first infecting another animal species – an intermediate host – that then comes into contact with people.

This is, one theory suggests, what triggered another coronavirus outbreak in China which first appeared in November 2002.

The Sars coronavirus, now known as Sars CoV-1, is thought to have jumped from bats to humans via the civet cat - a small furry mammal sold in the markets of southern China.

After the authorities failed to acknowledge the outbreak for several months, Sars went on to cause 774 deaths worldwide.

Nearly two decades later, the very first cluster of Sars CoV-2 cases appeared in Mr Wang’s Wuhan neighbourhood. One study found around half of them had a connection to the seafood market.

It was no surprise then that there was widespread speculation the virus’s intermediate host might have been among the animals on sale there.

But this theory now appears to have been dismissed by China, following the testing of samples taken from various places inside the market. While traces of the virus were found, none were detected on any of the animal samples. Officials have concluded that the outbreak is likely to have begun elsewhere, and that the crowded market simply helped spread the disease from person to person.

Most scientists remain convinced, though, that somewhere along the line, whether in a market or elsewhere, Sars-CoV-2 will have passed naturally from an animal to a human.

They point to an increasing number of such “spillover” events driven by factors such as population growth and human encroachment on natural habitats.

Dr Yuen Kwok-yung, a microbiologist from Hong Kong University who joined the Chinese National Health Commission fact-finding trip to Wuhan in January, says the “spillover” theory is the most favoured for the origin of this virus. This is not least, he says, because such events have happened so often before, from Sars CoV-1 to other avian-flu pandemics.

“H5N1 was the first wake-up, then Sars, then H7N9 in the Yangtze Delta, and now Sars-CoV-2,” he tells me.

“So, if you ask me what is the highest possibility – it’s that the virus is coming out from markets, markets that are selling wildlife.”

And that’s why, he argues, the trade in wild animals should remain the focus of prevention efforts.

“It is not easy to change culture, but we must,” he says.

Finding the source of the virus is not just a question of academic interest. If Sars-CoV-2 has come from a reservoir of infection in a particular animal species, then of course, it could continue to pose the risk of new outbreaks.

In mid-May, the World Health Organization passed a resolution calling for an international effort to trace the likely intermediate animal host. It has just announced it has been given permission to send a team of investigators to China for this purpose. But scientists agree it may not be an easy task.

We sent a number of questions to the Chinese National Health Commission and the foreign and science ministries about the work already being done in this regard. We asked if any studies had begun to test various animal species that could have spread the virus. We received no answers to our questions.

Outside the shuttered Huanan Seafood Market we’re stopped from filming. “I don’t care where you’re from,” a policeman tells me when I explain that I’m a foreign journalist. “China has done a lot to contain the virus. You need to promote positive energy.”

Mapping the virus

As Wang Fei lay dying in hospital, another location in Wuhan, a 40-minute drive from the Huanan Seafood Market, was already becoming the focus of an altogether different theory.

The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) was now at the centre of a growing storm of conspiracy theories, suspicions and allegations that the virus might have leaked from a lab.

They have continued to this day.

The WIV’s modernist, grey concrete and glass structure, set in a leafy campus with a small lake, is clearly visible from the adjacent road.

When we arrive there, we are quickly surrounded by security guards who tell us it’s a sensitive area and call the police.

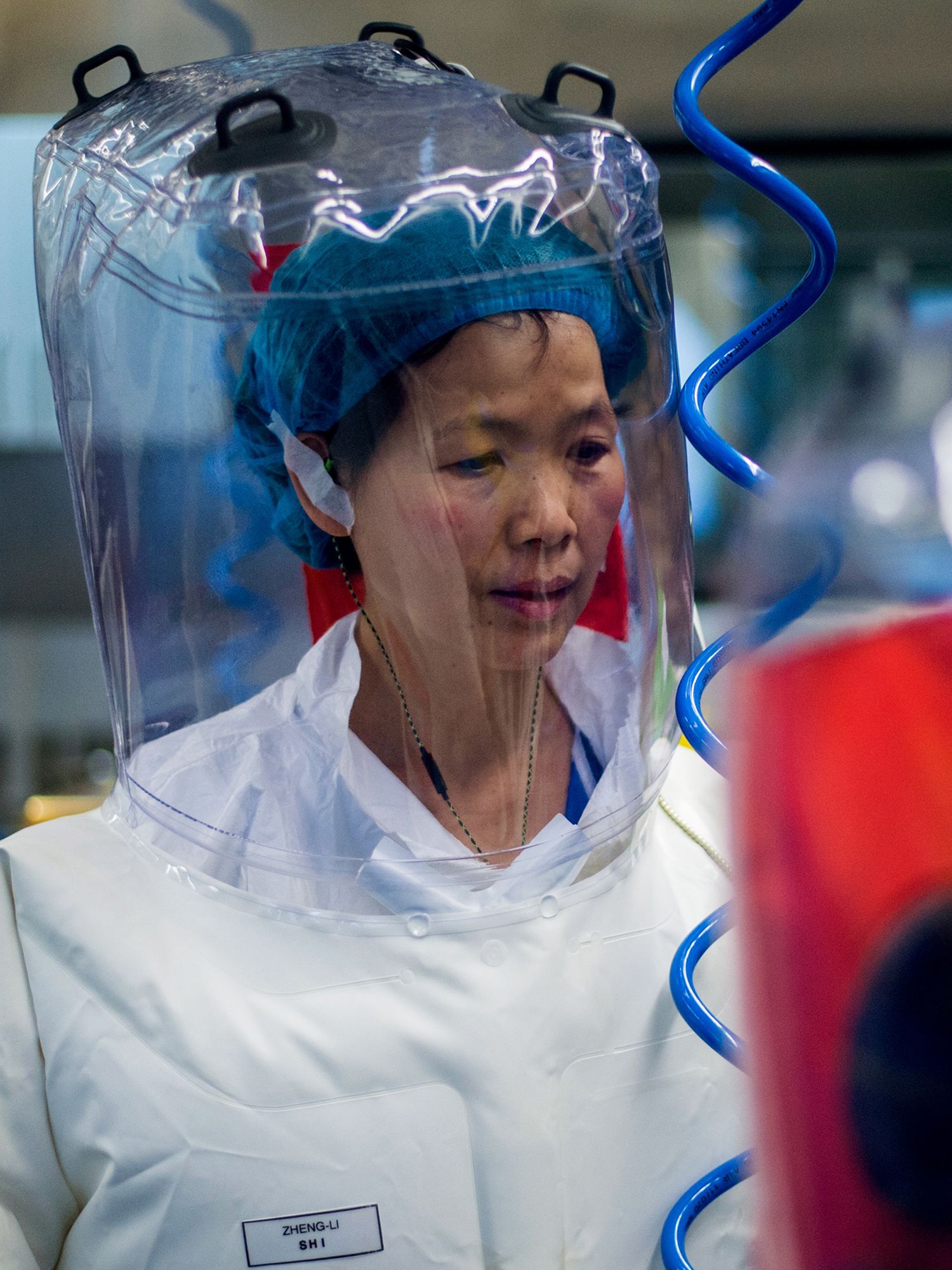

The institute is the world’s leading authority in the collection, storage and study of bat coronaviruses.

Its researchers are led by star scientist Professor Shi Zhengli – known as “Bat Woman” to her colleagues because of her expertise. They have spent years collecting samples from live bats in remote Chinese caves.

Professor Shi Zhengli in her lab

Professor Shi Zhengli in her lab

One recent paper, co-authored by Professor Shi, gives details about hundreds of bat coronaviruses, many of them previously unpublished, unveiling just how many have been gathered.

The research has included the genetic modification of some of these viruses, including the construction of new, chimeric – or hybrid – viruses, in order to examine their potential to infect humans and, potentially, cause pandemics.

It was Professor Shi who discovered and sequenced the genetic code of the nearest known relative of the Sars CoV-1 virus, found inside a bat from a cave in China's Yunnan Province.

Ever since the Sars CoV-1 outbreak, the fear of an even deadlier, more infectious spillover event has been the driving force behind Wuhan's coronavirus research.

- Viruses are tiny packages of genetic material wrapped in a protective envelope. Viruses rely on living hosts to help them make more viruses.

- They attach to a cell and then invade it via proteins on the surface of this envelope. Coronaviruses use jagged structures called spike proteins which give the viral envelope the appearance of a crown, or corona.

- Once inside, the cell's internal "machinery" is hijacked, forcing it to assemble copies.

On 2 January, just three days after becoming aware of the new virus circulating in Wuhan, she also became the first to sequence Sars-Cov-2.

Ironically, it is the genetic make-up of Sars-CoV-2 that has itself helped fuel the lab-leak theory.

Some subsequent studies, including one by Prof Shi, suggest that there is something different about its genome compared to other known coronaviruses of a similar type.

Its spike proteins – the pointy bits of the “crown” that latch onto the cells of an infected host – seem to bind extremely well to human cells.

While most viruses need time to adapt to a new host, Sars-CoV-2 appears to have been highly infectious from the beginning of the outbreak.

One paper compared the new outbreak with the original Sars epidemic. It found that Sars-CoV-2 was already “pre-adapted” for human infection.

The virus’ spike proteins also have a feature, unusual in Sars-type coronaviruses, known as a “furin cleavage site”. These are thought likely to increase the efficiency with which the virus can penetrate the human cells, take them over and replicate inside them.

It is this combination of factors – the WIV’s proximity to the outbreak, the kind of scientific work it was involved in, and the seemingly unusual nature of the virus itself – that have led to the highly controversial alternative to the natural “spillover” theory.

Claims that the virus leaked from a lab first began to circulate on the Chinese internet in early February.

There were unsubstantiated rumours the coronavirus may have passed from a lab-infected animal to the local community, or that one of the WIV researchers may have themselves become accidentally infected, either with a natural virus collected from the wild, or a lab-made one.

Conspiracy theories soon spread further afield, including claims in some foreign newspapers and websites that the virus may have been an engineered “bio-weapon”.

But none of the lab leak theories – animal virus, man-made virus, deliberate or accidental – have been backed up with any concrete proof, relying instead on conjecture and circumstantial evidence.

A group of Indian researchers were some of the first to use the virus’ genome to hint at the possibility of genetic modification in a lab.

But the paper was quickly debunked and was withdrawn.

However unusual the virus appeared to be, there was nothing to prove that its notable features could not have come directly from nature.

In early February, Shi Zhengli herself took to social media in response.

“I, Shi Zhengli, swear on my life that it has nothing to do with our laboratory,” she wrote, adding that those who spread rumours should “shut their stinking mouths”.

Sars-CoV-2 has a series of protein spikes that form a 'corona' or crown

Each protein spike has a number of receptor binding domains (RBD)

The RBD latches on to the ACE-2 receptor of a human cell, infecting the host

The Sars-CoV-2 protein spike also has furin cleavage sites which may increase its ability to infect the host

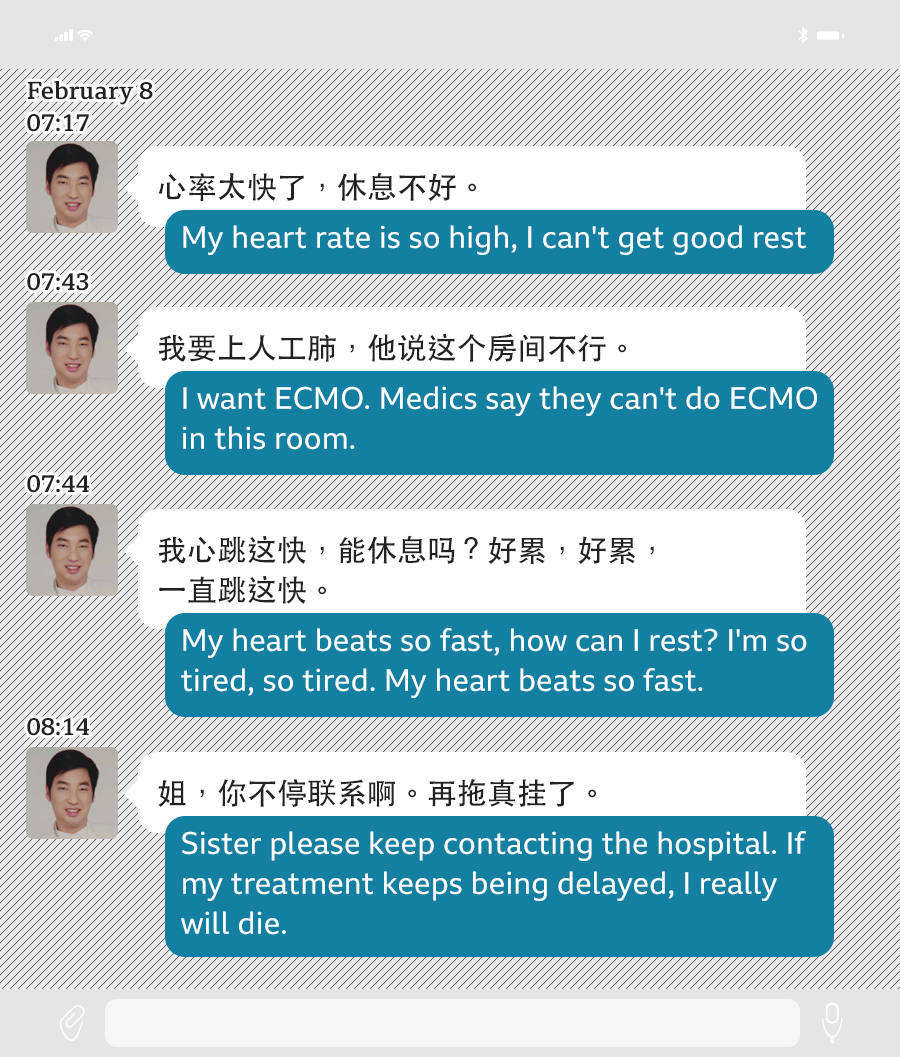

Meanwhile, Mr Wang was succumbing to some of the same notable qualities of the virus on which such theories were partly based.

It was a pattern of decline now all too familiar to medics everywhere.

His lungs were being ravaged by the pathogen, filling with fluid and white blood cells, and the oxygen in his blood was plummeting. “My heartbeat rate is 160 per min. My blood oxygen saturation is only 70. It’s killing me,” he texted his sister.

The following day, on 8 February, he sent one last message. “Please save me,” it read, “I can see stars.” He died a few hours later.

Manipulating viruses

On 30 April, the US president waded into the controversy. He was asked by a reporter: “Have you seen anything at this point that gives you a high degree of confidence that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the origin of this virus?”

“Yes, I have. Yes, I have,” Donald Trump replied.

Other administration officials have weighed in, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo blaming what he claimed was China’s “history of running sub-standard laboratories”.

But despite the US saying to have “enormous evidence” for a lab leak, none has been provided.

With the theory now central to an escalating geopolitical dispute between the US and China, critics of President Trump’s handling of the response at home see it as a sensationalist smokescreen to deflect domestic blame.

Mindful that they could be drawn into a quagmire of conspiracy and propaganda, some scientists, however, believe that the lab leak question should not be dismissed out-of-hand.

It relates, they say, to one of the major scientific debates of our time and it has implications not just for China but for the US government too.

The work of the WIV, in collecting large numbers of bat coronaviruses and experimenting on them, has not been a lone venture.

It has been part of a major international effort focused on the growing risk of spillover events and the threat of new, human pandemics.

Some of Wuhan’s research has involved collaborations with US scientists and the backing of generous amounts of US funding.

And its creation of chimeric viruses - the stitching together of parts of the genomes of different viruses to make new ones - uses an easily accessible technique commonplace in labs around the world.

Such research has been the subject of an intense disagreement between scientists about the benefits and risks of such research.

Supporters say it can help us to anticipate how viruses might emerge in the wild and has the potential to help with the development of medicines and vaccines.

Those against, say it risks doing the exact opposite.

Manipulating viruses – to make them more infectious or more deadly – could, they say, spark off a man-made pandemic with a lab-made virus.

The risks might include lab workers becoming infected – perhaps unknowingly – when collecting virus samples from animals in the field, when handling animals kept in the lab, or when experimenting with live viruses.

Since the Sars CoV-1 coronavirus outbreak, for example, there have been four separate leaks from labs studying that disease.

Two of the incidents were at the National Institute of Virology in Beijing in 2004.

During one of them, a researcher caught Sars after spending two weeks at the lab. She went on to infect her mother, who died, as well as a nurse, who in turn infected several other people.

The coincidence of a new pandemic coronavirus appearing in the same city as a laboratory devoted to studying them is something that Prof Shi Zhengli appeared to initially acknowledge.

When she learned of the outbreak at the end of December, her thoughts turned to the viruses stored in the institute's freezers.

In an interview with Scientific American, she says she remembers thinking that if coronaviruses had sparked the pandemic: “Could they have come from our lab?”

The debate

While the lab leak theory has smouldered away both online and in Washington political circles, it has largely been dismissed by scientists.

It is a scientific consensus that has, in turn, fed into mainstream media coverage, with now wide acceptance that a natural, spillover event is the most probable cause of Sars-CoV-2.

The dismissal is based not just on the fact that such spillovers have happened before, but on a key piece of evidence that has come from Prof Shi Zhengli herself.

Concerned to rule out her lab’s involvement in the outbreak, according to the Scientific American interview, she began “frantically” searching the experimental records and samples already stored in her lab.

Her February paper reported what she said was the closest match she was able to find.

A virus, which she named RaTG13, collected from a bat in 2013, showed a 96.2% similarity to Sars-CoV-2.

Although that sounds close, the 3.8% genetic difference between the two would, estimates suggest, take decades of evolutionary change to occur in nature.

If Sars-CoV-2 had leaked from her collection of coronaviruses, the lab would have contained either Sars-CoV-2 itself, or something much, much closer related.

“That really took a load off my mind,” Prof Shi told Scientific American. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

But the evidence that has undoubtedly had the most bearing on the discussion about a possible lab leak was contained in a paper published in March in the medical journal, Nature Medicine.

It has become widely accepted as proof that the virus was not made in a lab.

The unusual features of the Sars-CoV-2 spike protein discussed earlier – its high binding affinity to human cells and its furin cleavage site – must have, the authors argue, come from nature.

Their evidence is partly based on the use of sophisticated computer modelling. If a scientist had used such models in advance, they argue, to analyse how strongly the Sars-CoV-2 spike protein might bind to human cells, the results would predict a far weaker bond than actually turns out to be the case.

In other words, a computer would be unable to foresee the binding strength of the virus. Therefore, they argue, no scientist is likely to have set out to create it in a lab.

Furthermore, they imply, to create Sars-CoV-2 in a lab, you’d need to start with a virus with a much closer genetic match than RaTG13, the distant ancestor found in the Wuhan freezer. A new virus cannot be made from a virus that does not exist.

Far more likely, they say, that the virus picked up its notable features while circulating, undetected, in humans or animals for months or years before the outbreak.

“We very carefully considered a potential link to the lab - we did not dismiss this possibility out of hand,” the paper’s lead author Kristian Andersen, a professor of immunology and microbiology at the Scripps Research Institute in the US tells me.

“And it is clear - all the available data is fully consistent with a natural history of Sars-CoV-2. There is no scientific data showing any link to the lab.

“Most theories considering a link to the lab are conspiracy theories,” he adds. “They are exceptionally disruptive to the efforts of getting Covid-19 under control and result in unnecessary human suffering.”

Despite the wide acceptance of the conclusions reached by the Nature Medicine Paper, there are still some scientists who refuse to see it as conclusive proof that the virus wasn’t manipulated in some way.

Nikolai Petrovsky, a professor of medicine at Flinders University in Adelaide and Chairman and Research Director of Vaxine, a company leading Australia's search for a Covid-19 vaccine, believes that laboratory manipulation has to remain under consideration for being behind a possible explanation for Sars-CoV-2’s “surprising” ability to bind to human cells.

And he rejects the argument that if it wasn’t pre-planned by a computer model, it didn’t happen.

“In science a lot of things are done on the basis of give-it-a-go, and a lot of things happen completely by accident,” he tells me. “You know, a lot of Nobel prizes have been won on the basis of accidents.”

Others refer to Wuhan’s past experiments in which genome segments from different viruses have been stitched together to investigate how spike proteins bind to human cells.

And they point out that there is no way of knowing whether or not Wuhan does in fact have, among the hundreds of coronaviruses it has collected, anything closer in genetic make-up to Sars-CoV-2 than RaTG13.

What’s more, RaTG13 is itself the subject of some speculation.

The BBC has had it confirmed, from the researchers running a respected Chinese database, that it is the same virus as one that the WIV previously referred to as RaBatCov/4991in this paper.

There is no explanation for the change of name, but that 2016 paper makes it clear that the virus appears to be a new strain of Sars-type coronavirus.

Professor Petrovsky says it would be odd if the WIV, given its interest in such viruses, hadn’t continued to work on it. But there is no more mention of it at all until this year, when RaBatCov/4991 re-emerged under its new name RaTG13 as the closest known relative of Sars-CoV-2.

Professor Richard Ebright, a microbiologist and biosafety expert at Rutgers University in the US, says there is only one way to conclusively rule out any form of a lab leak. “A credible investigation would need unrestricted access by investigators to facilities, samples, records, and personnel, as well as unrestricted environmental sampling of facilities and serological sampling of personnel,” he tells me.

The US government said in a statement in April that the intelligence community does not believe the virus was modified or created, but the government continues “to rigorously examine emerging information and intelligence to determine whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or if it was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan”.

We put in a request to speak to Professor Shi Zhengli but it was turned down. We sent questions to the WIV asking whether any investigation had been carried out and, if not, whether they’d be willing to allow one. Again, there was no response.

Looking ahead

Wuhan’s lockdown lasted 76 days. Afraid that she might be infected, Ms Wang was too worried to join her mother at home, so stuck it out in the office, surviving on simple meals. She was joined by her brother’s 13-year-old daughter, while his widow, also infected with coronavirus, recovered in hospital.

“I kept writing down memories of my brother,” Ms Wang tells me, “and then posted them on social media in order to ease my empty feelings and hopelessness.”

After the lockdown was lifted on 8 April she emerged into a city that had, through an extraordinary collective effort and the forced ordeal of lockdown, vanquished the virus.

Today, Wuhan is returning to life. But the signs of the lingering economic impact can still be seen. In one of the usually vibrant night-markets people are eating and socialising again, but many of the tables are empty. “Customer numbers are down by two-thirds,” one woman selling boiled frogs tells me.

There are signs of something else here too. Early in the lockdown, in the chaos and confusion of that moment, the censorship controls appeared to briefly vanish.

People vented their anger on social media about the perceived official failings, and their grief, following the death of Dr Li Wenliang.

Today though, a different narrative has taken hold. “China united together to prevent the epidemic,” says another trader, selling yellow-croaker fish on sticks. “But you foreigners don’t know how to protect yourselves.”

And the market customers appear to have absorbed yet another origin theory which has been promoted by Chinese state media and some senior officials.

“I think the virus came from the US,” one woman tells me. “In the early stage of the outbreak, US soldiers were visiting Wuhan. They left early in a chartered plane.”

In the absence of independent evidence, politics and propaganda are filling the vacuum with both the US and China continuing to trade unsubstantiated allegations.

And without it, it is impossible to answer the big questions.

How might a spillover event be better contained next time? And how do we properly balance the benefits of the study of pandemic viruses, in a growing number of virology labs, against the risks?

Scientists who support such work are convinced that Sars-CoV-2 is an incentive to redouble their efforts. “The mission must go on,” Professor Shi Zhengli says, with a plan to sample bat viruses on a much bigger scale. Something Professor Richard Ebright, from Rutgers, calls the “definition of insanity”.

China has, under some diplomatic pressure, agreed to an independent investigation into the international response to the virus, although it is unclear what the remit will be, who will take part, and when it might happen. President Xi Jinping has stressed that it will have to wait until the pandemic is over.

Meanwhile Ms Wang says she intends to continue to fight for answers about her brother’s death. She insists the warnings from the police to keep quiet won’t stop her. “I’m a law abiding citizen,” she says. She does not want us to publish her full name simply to minimise the risk of online abuse, not because she is trying to hide from the authorities.

Sometimes it is in the individual stories that the true, global impact of the virus really hits home. Four months after Wang Fei died, Ms Wang has only just told her mother what really happened.

The family, fearing she would be unable to bear the news, allowed her to believe her son was still in quarantine. In the end, they could hide it no longer. “For several days my mum couldn’t fall asleep,” Ms Wang tells me. “A woman born before the founding of our country can’t understand why such a tragedy can happen in modern times.”

Watch: John Sudworth's report from inside Wuhan, 17 June 2020