The electoral rapids of the River Dee

Election battleground: Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire

As politicians campaign for votes, we will be looking closely at the places where the election could be won or lost. The two constituencies through which Scotland’s River Dee flows, from the Cairngorms to the port of Aberdeen, have changed hands at the last two elections, making them among the most fluid in Scotland.

By Jon Kelly

Some days, when he takes his labrador, Buddy, for a walk, Brian Cooper strolls five minutes from his home to the banks of the River Dee and watches it flow towards Aberdeen.

Brian grew up there in a two-bedroom tenement flat in Froghall, a council estate near the city centre. It was a close-knit place - his grandmother lived nearby, and an aunt and uncle too. Brian’s father was a bricklayer by trade, his mother variously a shop assistant, barmaid and carer. After leaving school at 16, Brian signed up for an apprenticeship with the Post Office.

Then, at 21, Brian landed a job as an office boy with one of the energy companies that proliferated in the city after the discovery of North Sea oil - his father was among the men who went to work offshore. It meant a pay cut for Brian at first, but he knew it was an opportunity. He rose quickly through the ranks, eventually becoming a project manager before moving into business development and sales.

Soon, Brian and his wife were able to buy an imposing detached house in the affluent suburb of Milltimber. Though it lies within the city boundaries, it feels like a village. In the summer, families have picnics by the banks of the river.

Brian, 37, isn’t the sort to put posters in the window of his home at election time. "I wouldn’t say I was a political animal,” he says. He’s well aware he doesn’t have all the answers. “I’m probably more of a distant spectator trying to form my own view.”

And so in 2014, as the referendum on Scottish independence approached, Brian carefully studied the arguments for and against. “I felt there were positives as an independent country,” he says. With its natural resources and human capital, he was confident Scotland could succeed on its own. “Scottish people are pretty resilient, we are pretty welcoming, we welcome others into the country - I always felt we would build something.”

That September, the morning after the No campaign’s victory was declared, Brian was disappointed. But he quickly picked himself up, accepting that a decision had been made, although he still believed that, in the long term, Scotland should be a nation state in its own right.

Then, nearly two years later, there was another referendum to consider - this time on the UK’s membership of the European Union. He hadn’t thought much about the issue before, but it seemed the original aims of the European project - to bring peace and stability to the continent - had been met. The crisis in the Eurozone made him wonder what the point of it was in the current era.

“You start thinking, ‘So it started out as something, but is it still serving that purpose to this day? The world we live in now, is that where we were when this bloc was formed?’ I think we live in a completely different time.”

On the morning of 24 June 2016, he woke to find that while Scotland had voted heavily to Remain, his side - Leave - had narrowly won across the UK as whole. He assumed the politicians at Westminster would do as they had been instructed and make Brexit happen. But as the years went on and they failed to do so, he grew increasingly frustrated.

“For me, I just think everyone now wants it done,” he says. He’d rather Brexit was completed before another independence referendum. “You need to take care of Brexit first, understand where it’s going to lead to.”

Brian’s support for both Scottish independence and Brexit isn’t shared by any of the major political parties. But he’s far from alone in his position. In 2017 the British Election Study estimated that Yes-Leave voters made up 17% of the Scottish electorate.

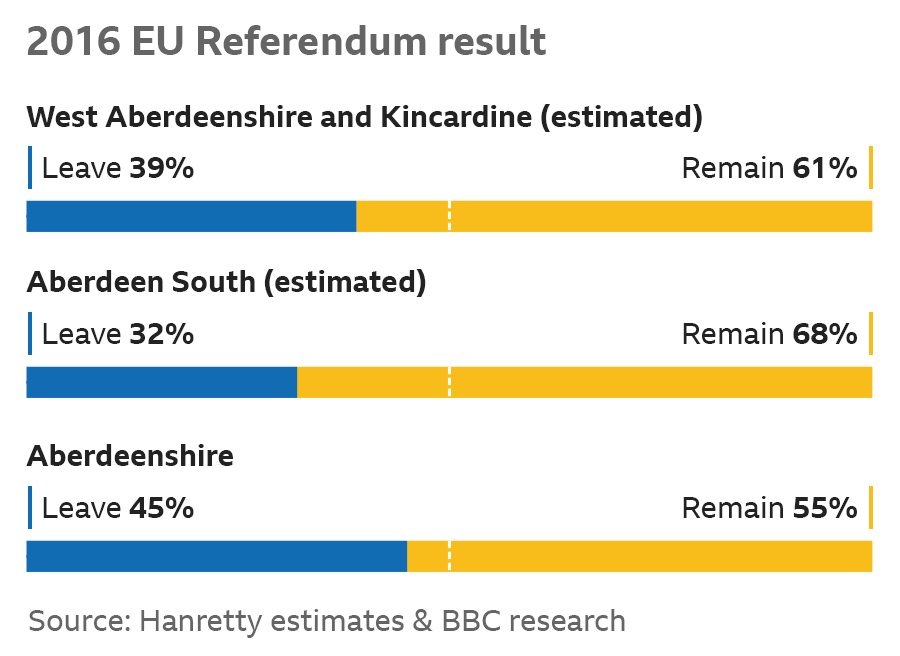

This part of Scotland voted mostly for Remain. In Aberdeen city, as in Scotland as a whole, more than 60% voted to stay in the EU. But in the surrounding local authority area – Aberdeenshire – the vote was closer: 55% voted Remain, with fishing communities along the north-east coast showing particularly strong support for Brexit.

In the wake of both referendums, the region has become highly volatile.

Aberdeen South, the constituency in which Brian lives, has been represented over the past decade by MPs from Labour, the Scottish National Party and the Conservatives. Neighbouring West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine, through which the Dee flows from its source towards the outskirts of the city, has been represented at Westminster over the same period by a Liberal Democrat MP, then one from the SNP, then a Tory.

The river - alongside the Don, one of two that passes through Aberdeen - descends from the expanse of the Cairngorms National Park, through the area around Balmoral known as Royal Deeside, past commuter towns like Banchory towards Aberdeen’s docks - a varied string of communities. As well as being an area of extraordinary natural beauty, it’s now among Scotland’s most fiercely contested political terrain.

Like Brian, Brid Ni Mhaoileoin lives five minutes' walk away from the Dee. But her view from Torry, a former fishing village long since subsumed by Aberdeen at the very mouth of the river’s south bank, is radically different. It overlooks Aberdeen Harbour, north-east Scotland’s key commercial port and the North Sea energy industry’s main support centre.

Its tidal waters are thick with commercial traffic, but Brid, 59, says there’s more to it besides. “You can see otters, herons, the wildlife round there is amazing,” she says. “You see all the boat clubs, and the guys out rowing at 6am. I love living this close to the river. I suppose it’s a lifeline.”

Brid grew up in Westport, Co Mayo. In 1984, with unemployment running high in the Republic of Ireland, Brid came to Aberdeen to visit her sister and never went back. Early on, she was struck by the sense of community and how quickly she got to know all her neighbours. She now works at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary as a medical technician, and considers Aberdeen her home.

Aberdeen is one of Scotland’s most prosperous places - a report by Demos and PwC ranked it the best city in Scotland to live and work in. But Torry hasn’t seen much of its wealth. It is ranked by the local authority as its most deprived community. “You can see the effects of poverty and austerity and lack of funding here,” Brid says. In recent years demand has skyrocketed at the local food banks. There’s also a recognition that, as the climate crisis intensifies, the reliance on oil and gas won’t last forever. “Aberdeen has always been a wealthy city, but it has always had its share of poverty,” says Brid. “If you don’t have a lot of money it’s a very expensive place to live.”

Brid had always taken an interest in politics, but the independence referendum transformed everything. As in many working-class areas of Scotland that had traditionally supported the Labour party, groups supporting the Yes campaign flourished in Torry. For supporters of independence, galvanised by the promise of remaking the nation, this explosion of enthusiasm was thrilling and liberating.

But Brid wasn’t one of them. She was sceptical about the prospectus set out by the Scottish government. “Of course Scotland would survive independence,” she says. “But honestly, a complete break and making yourself into a small community is not the way Scotland should go at the moment. In the same way as I voted no to Brexit, I think we need to stick together. It sounds really cliched, but united we stand, divided we fall.”

There was mutual incomprehension among those on either side of the divide. “I lost some friends over it,” Brid admits. “At my work I didn’t speak about it because I felt uncomfortable about the reaction I was getting.” She joined the Labour Party, and although she eventually ended up on the winning side in the 2014 referendum, the SNP’s landslide at the 2015 general election ensured it didn’t really feel like a victory for long.

But the biggest trauma was the vote to leave the EU. Her friends in Torry’s sizeable Eastern European community tell her of their fears that they’ll be sent home. She worries, too, that a trade deal with the US will open the NHS to privatisation. This hasn’t led her to re-evaluate her position on Scotland’s status within the UK: “There’s no guarantee we’ll get into the EU if we have independence.”

Brid doesn’t have much enthusiasm for a general election in December, when the Aberdeen skies turn dark by mid-afternoon. “It’s going to be absolutely cold, wet and miserable, and I think people will feel cold, wet and miserable,” she says. “They won’t want to stand at their front door at 8pm when it’s pouring with rain and you’re asking them, 'Who are you going to vote for?'”

The past few years have been equally gloomy for the brand of politics she supports. “But all we can do is keep fighting for that,” she says. “And hopefully things will come back to normal.”

Battlegrounds

The rain has just stopped falling as Chris Redmond unstraps the kayak from the roof of his car and carries it down to the riverbank. The morning’s downpour was a welcome arrival, swelling as it did the level of the Dee. “It’s really mellow and relaxed out there today,” he says. “Anything lower than this would be a bit scrapey.”

Chris, 35, first came to Deeside to visit relatives of his wife 11 years ago, while training to be a teacher. “On the drive home, there were lovely autumnal colours - it was this time of year - and I said I could see us living here some day.” Nine months later he was offered a job at the primary school in Aboyne, a village 30 miles west of Aberdeen.

Today Chris is chairman of the village’s canoe club, and he’s paddled the river from Linn of Dee to its tidal limit on the outskirts of Aberdeen. “The river is one of the most varied in Scotland. It’s just got fantastic scenery, a whole range of different rapids, and lots of great communities along the way as well. It starts off with all the small villages and it gets bigger as it goes along.”

It’s an idyllic location, but keeping his head above water isn’t just something Chris has to worry about when he’s on the river. Aberdeenshire is an expensive place to live - when he first moved to Aboyne, there were only two properties in the area he could afford to rent on a teacher's salary. Buying was an even bigger challenge, and though he managed it eventually he can see it's getting ever harder for key workers to put down roots. He fears the consequences. “Teacher shortages have a knock-on effect for children’s education. And that has a knock-on effect further down the line. And so on and so on.”

Chris says his is a typical “just about managing” family. He now works full time as a nursery manager, his wife is part-time, and, with two children to raise, “all it takes is one big cost, a big unexpected something, to put pressure on the finances”.

As well as the cost of living, he worries about how much there is in the area for young people - they are already a smaller proportion of the population here than in most other areas of the UK. And if they want to head into Aberdeen by bus, the cost and timetabling is often prohibitive.

Chris’s canoe club at least helps bring people of different age groups together. A few years ago he applied for European funding to build a storage facility for paddle sports enthusiasts - a green edifice on the banks of the river known affectionately as the Canoe Cathedral. “Without that, who knows where the club might have been?”

In 2014, Chris voted Yes to independence, although he remembers it as a closely balanced decision. “It was very much 50-50,” he recalls. “It was up for debate.” But the referendum on the EU was a different matter. He knew that Aberdeenshire's tourism industry was dependent on migrant workers to keep all the hotels, cafes and visitor attractions fully staffed.

So in the wake of the Leave vote, the arguments for Scottish statehood began to look even more convincing to Chris.

“I support a second referendum on independence,” he says. “With where we are, leaving the EU, I support Scotland rejoining the EU. Scotland is a nation that welcomes people from all different nations, we recognise the value both culturally in having a range of opinions, views, and also in terms of the economy. People who’ve moved in from Eastern European states take those jobs that [other] people don’t want to take, that we don’t have enough people for.”

Each morning, around 6:30-ish, Simon Blackett wakes up, gets dressed and pulls on his yellow wellington boots. Then he goes for an early morning half-hour walk around Braemar with his two chocolate-brown cocker spaniels.

This part of Aberdeenshire, shaped by the upper reaches of the River Dee, has been popular with visitors ever since Queen Victoria and Prince Albert made nearby Balmoral Castle their holiday home. Members of the royal family still attend Braemar's Highland Gathering. The allure of the place isn’t just historic - Fife Arms, a newly refurbished former coaching house in the village, with a Picasso in the drawing room, was recently named Hotel of the Year by the Sunday Times.

Simon, 65, knows every inch of the village. He runs his own tour company, is an elder of nearby Craithie Kirk, is chairman of the company that runs Braemar Castle on behalf of the community and, for good measure, is a stalwart of the local history group.

A Sandhurst-trained ex-Army officer, for 21 years Simon was the local Invercauld country estate’s resident factor - a traditional Scots word for someone who manages land on behalf of its owner. Some estates have adopted modern terms like “general manager”, but Simon prefers the old-fashioned title, even if “it did get a bit of a bad press with the Clearances” - factors having carried out mass evictions across the north of Scotland in the century or so after 1750.

That sort of ruthlessness wasn’t Simon’s style, but being in charge of a sporting estate like Invercauld was a huge undertaking. It stretches across 108,000 acres and comprises, among other things, a ski centre, a caravan park, forestry and holiday cottages. Simon had ultimate responsibility for running the lot.

“It was 24/7,” he recalls. “You are taking on a lifestyle rather than a nine-to-five job. People would ask you questions at any time. I was lucky enough to have a family who enjoyed it. It was a brilliant job and I picked up an awful lot of knowledge.”

Simon’s time in charge of Invercauld was an era of great upheaval for rural Scotland. It saw the introduction of right-to-roam legislation by the Scottish Parliament and the creation of the Cairngorms National Park, with Braemar its centre.

The river was changing, too. It had long been a hugely popular spot for fishing. Historically, visitors paid for their holidays by selling the fish they caught. But when it became clear fish stocks were dwindling, in part because the water was heating up, a catch-and-release system with barbless hooks was introduced.

Although coachloads of visitors pour into Braemar throughout the summer, Simon says there's sometimes a sense in rural Scotland of being ignored. “There’s a feeling in our part of the world that Scotland tends to be central belt-dominated, because that’s where most people live and that’s where the votes are and where most of the politicians are,” he says.

Living in Braemar, with its reliance on tourism, Simon didn’t see Brexit coming. “You didn’t meet many people who gave good reasons to get out,” he says. Then, shortly before the EU referendum, he drove to a 90th birthday party in Hereford. “We kept going through these English cities and there were banners everywhere and I said to my daughter: ‘This is real. This is scary stuff. These people mean it.’”

But unlike Chris, he doesn't want to see another referendum on independence. “I’m quite happy to admit I’m a unionist and we have to think incredibly seriously, particularly now we’ve had the experience of Brexit, do we really want to inflict this on the country at this particular moment?”

Simon doesn't feel Scotland's referendum divides have scarred the country irreparably - political differences haven't driven a wedge between him and his wife, an SNP councillor. But the path ahead leaves him uncertain.

“I have a vote in this coming election, but I don’t know how I’m going to use it, because it’s really confusing," he says. "And whatever traditional party you might have voted for in the past, they seem to be standing for something different now, and there’s a lot of subliminal messages saying, 'If you want to leave you vote Tory, and if you want to remain you vote Labour,' which is an odd way of looking at it. It’s unhelpful - it’s really, really unhelpful - to the electorate. But we’re all going to have to make a decision.”

And so will the rest of Deeside. Meanwhile the river flows on, from Braemar down through Aboyne, through Aberdeen past Torry and out into the world.

For a full list of general election 2019 candidates standing in Aberdeen South and West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine see our pages below:

Aberdeen South parliamentary constituency

West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine parliamentary constituency

Credits:

Author: Jon Kelly

Online Producer: James Percy

Graphic Designers: Irene de la Torre Arenas and Sean Willmott

Researcher: Chris Marshall

Photographer: Paul Campbell

Photo Editor: Phil Coomes

Editor: Stephen Mulvey

More from BBC News

Aberdeen South parliamentary constituency

West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine parliamentary constituency