When council estates were a dream

Joanne has lived in Wythenshawe for half a century.

She lives on the estate with her partner Nelly and their son in the Benchill neighbourhood.

Joanne

Joanne

Their house is semi-detached, with pastel-coloured render covering the exterior and a red tiled roof. There are a couple of satellite dishes. In the concrete front garden the family car is parked.

Light floods the living room. There is an imposing fireplace, topped with a mirror. “I love the fireplace,” says Joanne. “I’m proud that I put it in myself.”

She owns the house but it hasn’t always belonged to her. Until 2005 she rented it from the council.

The improvements are worth it, she thinks. “My dad used to tell me - that when I close my front door, my house is my castle. I have to make my space comfortable.”

Her work has maximised the space. “I’ve taken out the kitchen toilet and have made a larder for my jars in its place.”

A sign in the kitchen reads: “Joanne’s Kitchen: Where friends meet and hearts warm.”

But her favourite place is the back garden. Filled with lush plants and bushes, and dotted with stone features, the garden has a narrow pathway that curves through a patch of neatly trimmed grass.

It’s a tranquil space and testament to two things - the pride former tenants take in their houses and the century-old spirit of the garden city.

Joanne with her partner Nelly

Joanne with her partner Nelly

Joanne moved to the area when she was seven, with her parents and six siblings. She still remembers people telling stories about the early days of Wythenshawe.

“It felt like the countryside, I was told. There were horses in the fields - much more of a green belt than what it’s now become.”

Wythenshawe is one of the oldest council estates in the UK and was one of the largest. But it has had to endure criticism over the years.

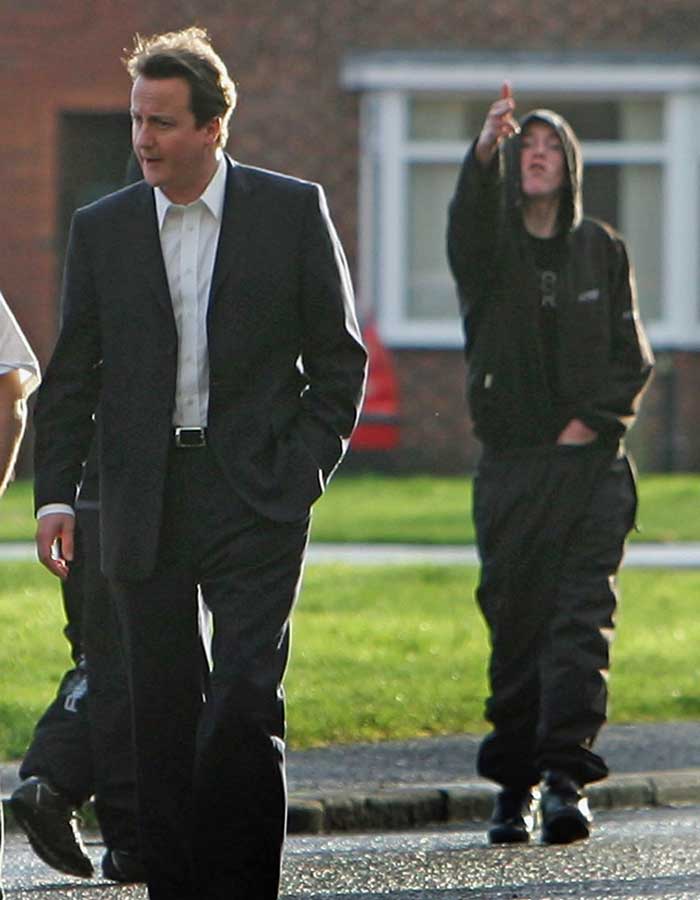

In 2007, when Conservative leader David Cameron wanted to highlight the issue of anti-social behaviour, he went to Wythenshawe. A photograph of a hooded youth pointing his fingers like a gun was widely used in newspapers.

Parts of the comedy Shameless were filmed in Wythenshawe, and last year a Channel 5 documentary was criticised for highlighting sensationalist comments about the area. One person said: “To be beaten to death on the way to buy a pint of milk from the shops would be quite commonplace.” There was annoyance locally at the negative portrayal.

But these views aren’t just restricted to Wythenshawe. This is a sharp stigma affecting many estates across the UK. Joanne has been on both sides of a divide in perception.

“When you tell people you own your own home - they approve. If you don’t they look down on you. It’s terrible if they find out you live in council housing,” says Joanne.

Joanne's view is one that I can relate to. I once feared what people would think of me.

Having grown up in foster care in south-east London for most of my childhood - I left the care system at 18. I had to bid for council flats. I can still recall the shame and unease and the overwhelming anxiety - wondering what people would think of me for living in a council flat.

Despite the hardship of growing up in care and being shunted between five different foster homes and care homes – I was fortunate to gain a place at Cambridge University to study history.

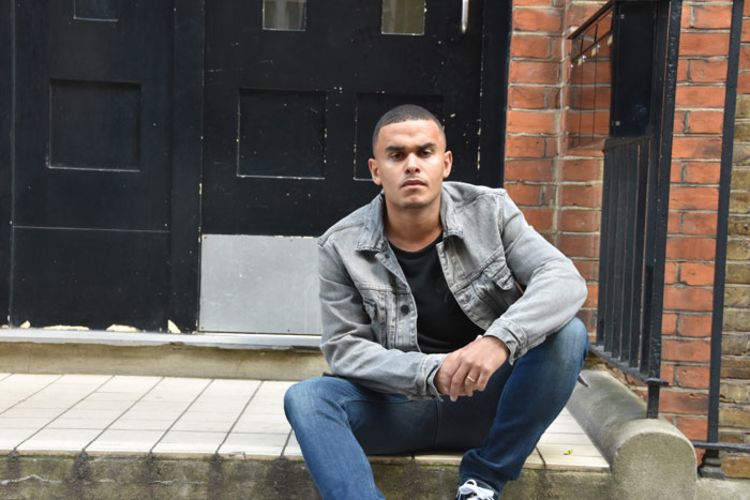

Ashley John-Baptiste

Ashley John-Baptiste

One of my biggest fears about going to such an elite university, full of privilege, was - what would people think of me for living in a council flat? As a result of my inner fear, I shied away from talking about home.

While I couldn’t pinpoint where attitudes stemmed from or why they existed - I was always paranoid about what people would think of me for living in a council home. As a result, I avoided telling people.

The stigma that many tenants now feel is a long way away from the original spirit that drove the construction of council houses.

Wythenshawe and dozens of estates around the country were born out of an extraordinary change 100 years ago - a vision of how housing should be in a country recovering from a cataclysm.

Joanne has lived in Wythenshawe for half a century.

She lives on the estate with her partner Nelly and their son in the Benchill neighbourhood.

Joanne

Joanne

Their house is semi-detached, with pastel-coloured render covering the exterior and a red tiled roof. There are a couple of satellite dishes. In the concrete front garden the family car is parked.

Light floods the living room. There is an imposing fireplace, topped with a mirror. “I love the fireplace,” says Joanne. “I’m proud that I put it in myself.”

She owns the house but it hasn’t always belonged to her. Until 2005 she rented it from the council.

The improvements are worth it, she thinks. “My dad used to tell me - that when I close my front door, my house is my castle. I have to make my space comfortable.”

Her work has maximised the space. “I’ve taken out the kitchen toilet and have made a larder for my jars in its place.”

A sign in the kitchen reads: “Joanne’s Kitchen: Where friends meet and hearts warm.”

But her favourite place is the back garden. Filled with lush plants and bushes, and dotted with stone features, the garden has a narrow pathway that curves through a patch of neatly trimmed grass.

It’s a tranquil space and testament to two things - the pride former tenants take in their houses and the century-old spirit of the garden city.

Joanne with her partner Nelly

Joanne with her partner Nelly

Joanne moved to the area when she was seven, with her parents and six siblings. She still remembers people telling stories about the early days of Wythenshawe.

“It felt like the countryside, I was told. There were horses in the fields - much more of a green belt than what it’s now become.”

Wythenshawe is one of the oldest council estates in the UK and was one of the largest. But it has had to endure criticism over the years.

In 2007, when Conservative leader David Cameron wanted to highlight the issue of anti-social behaviour, he went to Wythenshawe. A photograph of a hooded youth pointing his fingers like a gun at Cameron was widely used in newspapers.

Parts of the comedy Shameless were filmed in Wythenshawe, and last year a Channel 5 documentary was criticised for highlighting sensationalist comments about the area. One person said: “To be beaten to death on the way to buy a pint of milk from the shops would be quite commonplace.” There was annoyance locally at the negative portrayal.

But these views aren’t just restricted to Wythenshawe. This is a sharp stigma affecting many estates across the UK. Joanne has been on both sides of a divide in perception.

“When you tell people you own your own home - they approve. If you don’t they look down on you. It’s terrible if they find out you live in council housing,” says Joanne.

Joanne's view is one that I can relate to. I once feared what people would think of me.

Having grown up in foster care in south-east London for most of my childhood - I left the care system at 18. I had to bid for council flats. I can still recall the shame and unease and the overwhelming anxiety - wondering what people would think of me for living in a council flat.

Despite the hardship of growing up in care and being shunted between five different foster homes and care homes – I was fortunate to gain a place at Cambridge University to study History.

Ashley John-Baptiste

Ashley John-Baptiste

One of my biggest fears about going to such an elite university, full of privilege was – what would people think of me for living in a council flat? As a result of my inner fear, I shied away from talking about home.

While I couldn’t pinpoint where attitudes stemmed from or why they existed - I was always paranoid about what people would think of me for living in a council home. As a result, I avoided telling people.

The stigma that many tenants now feel is a long way away from the original spirit that drove the construction of council houses.

Wythenshawe and dozens of estates around the country were born out of an extraordinary change 100 years ago - a vision of how housing should be in a country recovering from a cataclysm.

Homes for heroes

On 23 November 1918, less than a fortnight after the end of World War One, Prime Minister David Lloyd George set out his vision.

“What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.

“There are millions of men who will come back. Let us make this a land fit for such men to live in. There is no time to lose.”

The era of the council home started with an influx of returning soldiers, sailors and airmen and the feeling they should not return to the slums of the pre-war era.

There was broad support for lower-density housing built on cheaper, rural land.

There had been public housing in Britain in the 19th Century built by philanthropists, charitable trusts and councils. But the end of World War One saw the first concerted nationwide effort for public house construction. Standards were to be improved.

Towards the end of the war, the architect and MP Sir John Tudor Walters and a committee of experts were asked by the government to create a blueprint for housing for working-class people. One of the experts was Raymond Unwin, an architect and planner who had been a major figure in the garden city movement.

The committee’s 1918 report was hugely influential.

The experts had investigated virtually every aspect of housing. “Medical opinion is unanimous as to the importance of allowing plenty of sunshine to penetrate into the rooms,” the report said. It recommended a general distance of 70ft between rows of houses facing each other.

There would be 12 houses to an acre in urban areas and eight in rural areas.

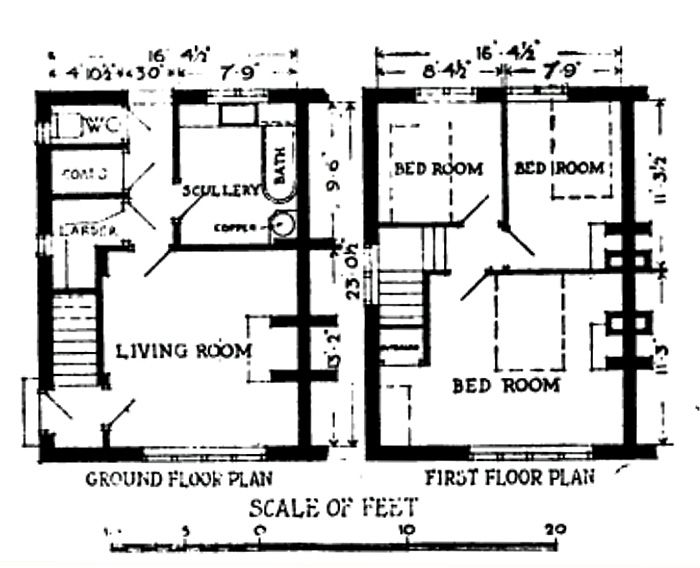

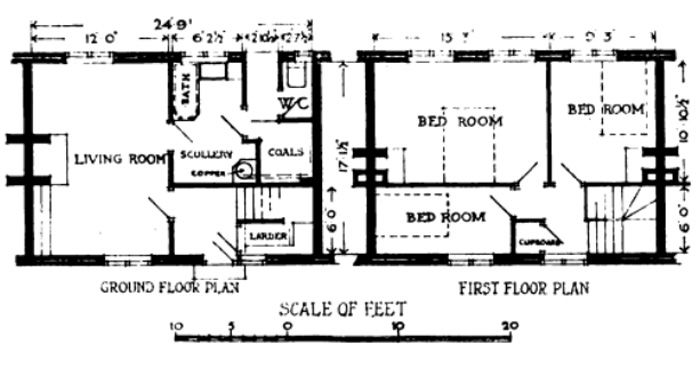

One of the biggest questions the committee addressed was whether houses needed parlours - a room in addition to the living room and scullery (kitchen).

“The desire for the parlour or third room is remarkably widespread among both urban and rural workers,” the report said.

“Witnesses state that the parlour is needed to enable the older members of the family to hold social intercourse with their friends without interruption from the children, that it is required in cases of sickness in the house, as a quiet room for convalescent members of the family… that it is needed for the youth of the family in order that they might meet their friends.”

Walters thought there should be parlours in a large proportion of houses in all schemes but without reducing the size of the other rooms.

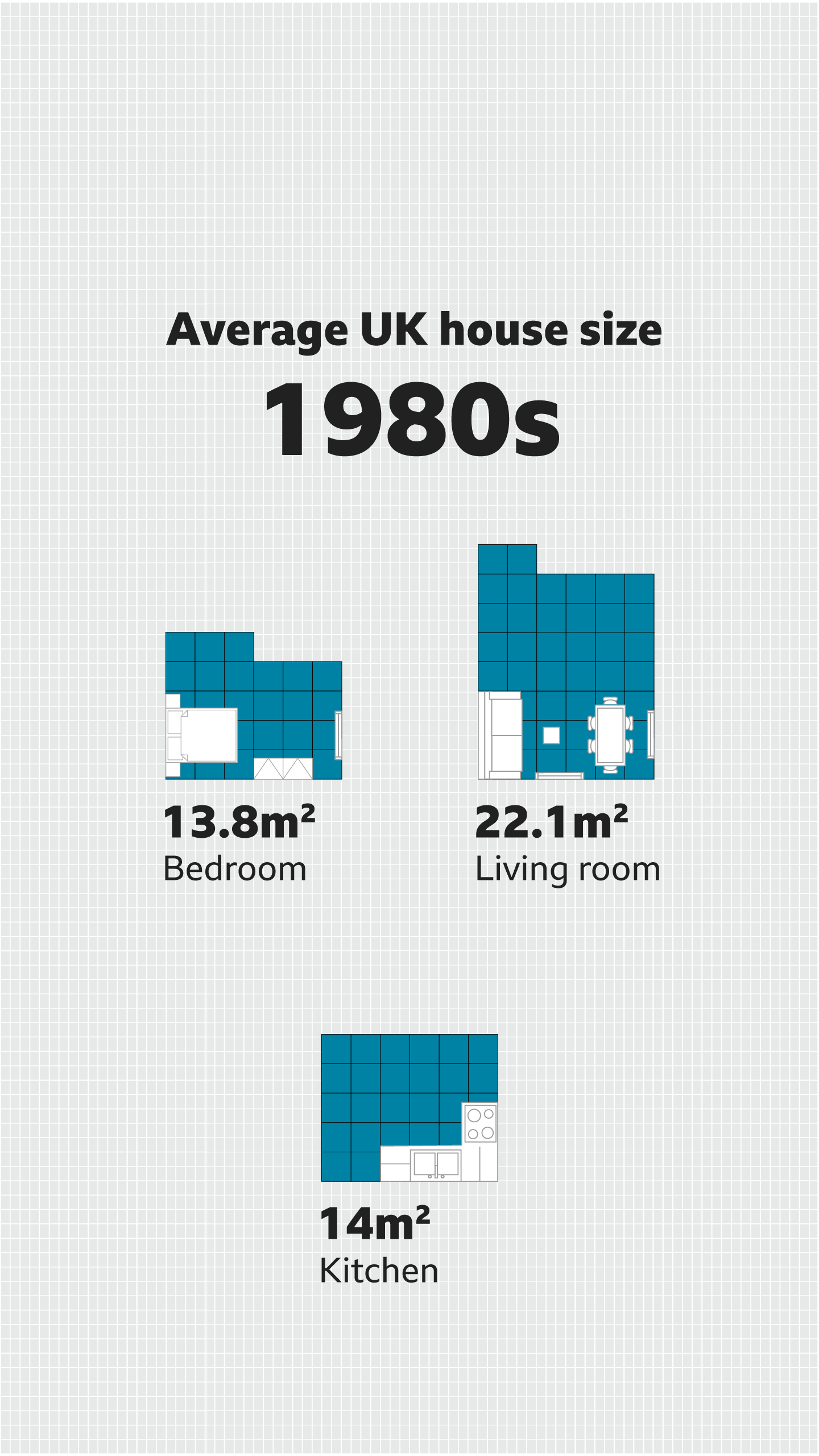

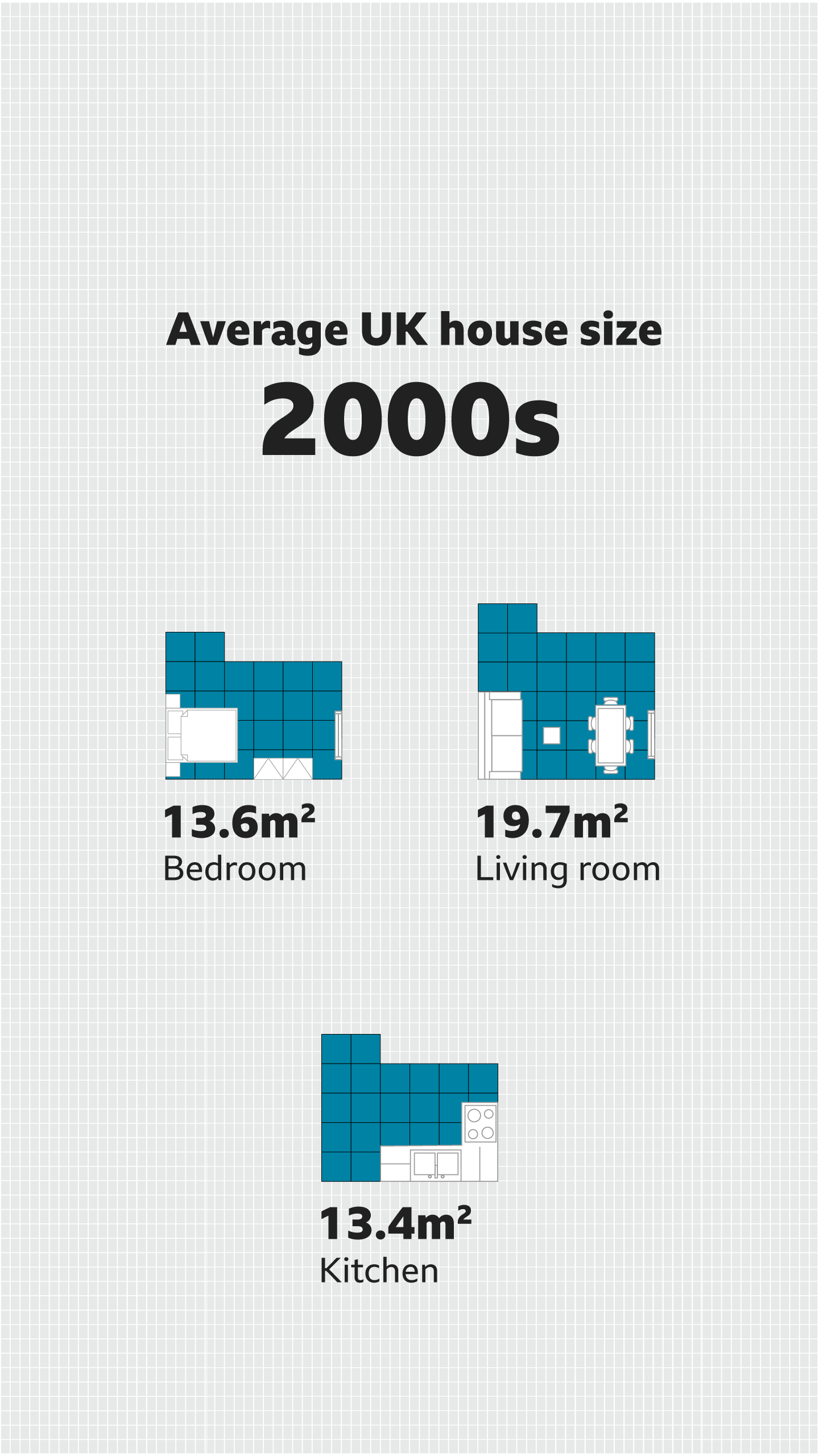

The ceilings in the houses would be 8ft high on average. (That's slightly higher than the typical standard in the UK today - 2.4m or 7ft 10in.)

The smallest houses without parlours would be well over 800 sq ft and the largest with parlours would be over 1,100 sq ft. Even in the smaller houses, the smallest bedroom would be 8 x 8ft.

Walters demanded basic standards and facilities. These new houses would each have a bath, and three bedrooms.

1929: Becontree in Essex was one of the first council estates in England

1929: Becontree in Essex was one of the first council estates in England

The committee had created a series of templates for houses that councils could use as a starting point. They were to be pleasant to live in but economical with materials and labour.

The committee’s work helped inspire the 1919 Housing and Town Planning Act. Known as the Addison Act, after the then minister of health, the new legislation provided councils with subsidies to build houses in areas where there was high demand.

Manchester was one of the cities that desperately needed new housing.

In March 1920, town planner Patrick Abercrombie identified Wythenshawe as the only undeveloped land suitable for building a housing estate close to the city.

It was intended to be a garden city, separated from Manchester by a stretch of green belt. In December that year, the Corporation of Manchester decided to purchase 2,500 acres of land.

1930: Construction in Wythenshawe

1930: Construction in Wythenshawe

Building started in earnest after 1931 when Wythenshawe was redesignated as part of Manchester.

By 1945 its Royal Oak, Benchill and Sharston neighbourhoods had an estimated combined population of 21,000.

As estates like Wythenshawe developed across the country they significantly altered the landscape of British housing.

The Becontree estate near Barking was started in 1921 and saw the building of 25,000 houses by 1935.

According to social historian John Boughton, council houses were initially for the more affluent working classes. They were far from slum housing. “They had a sense of being respectable and of higher status; for those with larger, steady incomes.”

Even with fluctuating grants, council building continued throughout the interwar period but it wasn’t until after World War Two that council housing moved to its next stage. Bombing had left the country needing hundreds of thousands more homes.

1937: Aerial view of Wythenshawe

1937: Aerial view of Wythenshawe

Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government built more than a million homes, 80% of which were council houses.

With resources tight there were cheaper solutions employed.

Prefabs - factory built, single storey, temporary bungalows - were expected to last for only 10 years, but they proved popular with many residents. Some prefabs lasted decades beyond their planned lifespan.

Wythenshawe had its share. “We called them the tin houses,” says Joanne. “Anytime it rained, you’d hear a lot of noise.”

In addition to prefabs, a new form of construction was pioneered - Precast Reinforced Concrete (PRC). These houses were quick and cheap to build and intended to last much longer than the prefabs.

1949: Post-WW2 construction in Wythenshawe

1949: Post-WW2 construction in Wythenshawe

Joanne lives in a PRC.

“This is a concrete house,” she says glancing around her living room. “The bedrooms could have been designed better though; they are too small... [the] staircase too narrow.”

I got my first indoor toilet when I moved to Wythenshawe with my family in the 1970s... We were delighted

Slum clearance continued in the 1950s with the Conservatives in power. Over the next couple of decades millions were uprooted from cramped, rundown inner-city terraces and rehoused in purpose-built new towns or in flats in high-rise blocks.

Many families had their first indoor toilet. Joanne still vividly remembers hers.

“I got my first indoor toilet when I moved to Wythenshawe with my family in the 1970s. It was posh. We didn’t have to go outside in the dark. We were delighted.”

The way working-class Britons lived had changed. By the end of the 1970s there were nearly 6.5 million council homes - but another change was coming.

Manchester was one of the cities that desperately needed new housing.

In March 1920, town planner Patrick Abercrombie identified Wythenshawe as the only undeveloped land suitable for building a housing estate close to the city.

1930: Construction in Wythenshawe

1930: Construction in Wythenshawe

It was intended to be a garden city, separated from Manchester by a stretch of greenbelt. In December that year, the Corporation of Manchester decided to purchase 2,500 acres of land.

By 1945 its Royal Oak, Benchill and Sharston neighbourhoods had an estimated combined population of 21,000.

As estates like Wythenshawe developed across the country they significantly altered the landscape of British housing.

1934: Brownley Road, Wythenshawe

1934: Brownley Road, Wythenshawe

The Becontree estate near Barking was started in 1921 and saw the building of 25,000 houses by 1935.

According to social historian John Boughton, council houses were initially for the more affluent working classes. They were far from slum housing. “They had a sense of being respectable and of higher status; for those with larger, steady incomes.”

Even with fluctuating grants, council building continued throughout the interwar period but it wasn’t until after World War Two that council housing moved to its next stage. Bombing had left the country needing hundreds of thousands more homes.

1937: Aerial view of Wythenshawe

1937: Aerial view of Wythenshawe

Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government built more than a million homes, 80% of which were council houses.

With resources tight there were cheaper solutions employed.

Prefabs - factory built, single storey, temporary bungalows - were expected to last for only 10 years, but they proved popular with many residents. Some prefabs lasted decades beyond their planned lifespan.

Wythenshawe had its share. “We called them the tin houses,” says Joanne. “Anytime it rained, you’d hear a lot of noise. They were knee jerk responses to the war. Not thought out.’

In addition to prefabs, a new form of construction was pioneered - Pre-cast Reinforced Concrete (PRC). These houses were quick and cheap to build and intended to last much longer than the prefabs.

1949: Post-WW2 construction in Wythenshawe

1949: Post-WW2 construction in Wythenshawe

Joanne lives in a PRC.

‘This is a concrete house,’ she says glancing around her living room. “The bedrooms could have been designed better though; they are too small... staircase too narrow.”

I got my first indoor toilet when I moved to Wythenshawe with my family in the 1970s... We were delighted

Slum clearance continued in the 1950s with the Conservatives in power. Over the next couple of decades millions were uprooted from cramped, rundown inner-city terraces and rehoused in purpose-built new towns or high rise blocks.

Many families had their first indoor toilet. Joanne still vividly remembers hers.

“I got my first indoor toilet when I moved to Wythenshawe with my family in the 1970s. It was posh. We didn’t have to go outside in the dark. We were delighted.”

The way working-class Britons lived had changed. By the end of the 1970s there were nearly 6.5 million council homes - but another change was coming.

Right to buy

Joanne’s family came to Wythenshawe because of her dad’s job as a firefighter. The house effectively came with the job.

“It was a sunshine house. You had two massive windows at the front and at the back. Our bedroom, which I shared with three of my siblings, would get flooded with light in the morning.

“I remember moving here and having a garden to play in - that was the first thing I noticed. We shared it with our neighbours,” she smiles with fondness.

Joanne holds a photo of her father

Joanne holds a photo of her father

The house had three bedrooms, but with six siblings, Joanne got used to sharing.

“I loved that house. I especially loved my bedroom. I decorated it myself - in pink flowered wallpaper and blooms. I also had a lot of cat pictures and Man City posters.

“I remember the living room wallpaper too. It was a print which had a butterfly design. I also remember my mum trying to be ultra modern at the time by hanging plates on the walls.”

Joanne’s family might have expected to continue renting the house for some time but the general election in 1979 changed the future of council housing.

One of the defining policies of Margaret Thatcher’s time in office was quickly introduced - right to buy.

Council house sales were a key policy for Margaret Thatcher's government

Council house sales were a key policy for Margaret Thatcher's government

The 1980 Housing Act gave secure tenants of three years or more in England and Wales the right to buy their council house or flat with a large discount on the market value. The act also provided for 100% mortgages.

Not long after it came into force, Joanne’s parents bought their council home in Wythenshawe for £7,000.

“At the time it was really exciting. People got huge discounts.”

The policy was welcomed by many council tenants - between 1980 and 1998, 1.3 million council homes were sold at discount in England. It was particularly popular in London and the south. In Greater Manchester, which includes Wythenshawe, 52,000 council homes were sold off.

Supporters of right to buy saw it as a chance for aspirational working-class people to own their own homes and improve their life prospects.

“They still live in that house now,” says Joanne, “and they often mentioned that buying their council home meant they’d have something to leave behind for the rest of us.”

But, while the idea had been floated by Labour in the past, and had been Conservative policy since 1974, it came to be intensely controversial.

Labour leader Michael Foot predicted it would lead to a dangerous depletion in council housing stock.

For later critics - it was at its essence a policy which squandered public assets, distorted house prices and ultimately helped lead to the housing crisis.

Joanne feels the reduction in council house stock is still being felt today.

“We really do need more council homes now - everything’s becoming private around here. My disabled daughter had to wait eight years to get a council house in the area.”

Joanne’s 25-year-old son, who is a plasterer, still lives with her because he can’t get a council home in the area. He also cannot afford to rent privately. “He’s probably gonna have to move to Bolton,” she says.

During the time many council homes were being bought by residents, fewer homes were also being built.

And despite the initial enthusiasm for right to buy among many working-class people, attitudes grew increasingly divided over the scheme. This is something Joanne relates to.

“It was a good idea at the start but it soon changed the vibe around here. The new home owners in Wythenshawe eventually began looking down on the ‘the council house scum’ and vice versa.

“When my parents bought their council home, they automatically became snobs in the eyes of many council tenants. Right to buy divided Wythenshawe - right to buy has definitely fed into the stigma.

“When you think right to buy, you straight away think of someone who cares about their life and works hard; when you think council tenant - you think scrounger. This just isn’t true though.”

For the supporters of right to buy it was a massive landmark in the drive towards a property-owning country.

In his biography of Margaret Thatcher, Charles Moore wrote: “It produced huge political loyalty to Mrs Thatcher, often from people who had never voted Conservative before… By 1983, it would become commonplace for people, mainly from the upper working class, to declare ‘Maggie got me my house’. ”

But social historian John Boughton believes right to buy helped create “residualisation”. Most of the people who bought their homes were the better off residents. The remaining tenants were increasingly the poorer families.

“Council housing became housing of last resort [as opposed to] what it used to be - housing for the affluent working class.”

The 1980s led to a shift in the public’s view.

“This period marked the low point of public perception - it was stigmatised and seen as poor housing, slum housing,” says Boughton.

The stigma

Clare’s life in Wythenshawe spans more than four decades. Four different council houses. Three children.

Her whole life has been spent in this council estate on the southern edge of Manchester.

“I grew up here; went to school here; worked here for a while. My kids were born and baptised here.”

Wythenshawe in the 1970s

Wythenshawe in the 1970s

Clare’s house is a three-bedroom terrace that’s typical for her part of Wythenshawe - layered by red bricks and a black tiled roof. A small chimney pokes out halfway along the roof, with a little black satellite perched on top. Spliced into the red bricks are white PVC windows. There’s some ivy on the front of the house.

The front garden is big enough for her to park her red Citroen and keep two black bins. Neatly trimmed, lush green bushes line the side of her house.

The 42-year-old moved there after her husband suddenly died of a brain haemorrhage in 2009.

“I met my Derek in 1997 - just three months after I had my first kid. He grew up in Salford but eventually moved onto the estate.

“We met at the Wythenshawe Civic Centre. He asked me for a drink.

“He was a black, Jamaican man; just lovely. In the 90s, you didn’t get a lot of mixed couples round here. It was very white back then, but we were on the same wavelength,” she says.

Clare's late husband Derek died suddenly in 2009

Clare's late husband Derek died suddenly in 2009

“Derek doted on the kids. He loved them to pieces. He was just 42 when he died. It was really sudden.

“I had to move. I just couldn’t stand the thought of staying in the home he once lived in. It was a horrible time for me and the kids.”

After deciding she wanted to stay in Wythenshawe, Clare did a council house swap.

Clare’s street is full of red-brick semis just like hers - only the colours of the front doors break the symmetry.

Wythenshawe retains plenty of greenery. Many houses look out onto large green open spaces. It’s in the spirit of the garden city movement that built Wythenshawe in the countryside nearly 100 years ago. But the vision that built it has dissipated over the years.

“I can’t recall a time in my life when people didn’t look down on us because of where we live. Was there ever such a time?” says Clare.

Even though she has come across old photos and stories of Wythenshawe, it’s almost incomprehensible to Clare that her estate could have ever been seen as a desirable place to live in by people from outside the area.

“If you’re from here, you love Wythenshawe heart and soul, but people from outside see us as scum. Even the cab drivers don’t like dropping people off here.

“Even as a kid, growing up around here was looked down upon,” says Clare.

The media plays a part in creating a negative image of council house tenants, Joanne believes.

“There is always good and bad wherever you live. There are a lot of good people around here too – people just don’t get to see it.”

Months before the Duchess of Cambridge visited a primary school in Wythenshawe in 2013, the playground of the school was vandalised and set alight. It received widespread media coverage.

“There was nothing positive being shown of our area when the duchess visited,” claims Joanne. “The papers made out as if she was coming to visit hell.

“The media gives people the impression that none of us work and that we are all scroungers. Most people in Wythenshawe work. Even some single parents do.

“Women round here are tough and hard working. People don’t hear about that.”

1970: Welshpool Close, Wythenshawe

1970: Welshpool Close, Wythenshawe

Clare shares Joanne’s view.

“The stigma of council housing has been there for years and years. I’ve even had colleagues in the past make digs about where I come from; or sometimes it’s a subtle look that you pick up.”

While Clare is undoubtedly proud of her home, she admits that at times, she feels the pervasive attitude that regards living on an estate like hers as negative; something that’s a bit shameful and unaspirational.

But despite this, she seems resilient.

“At the end of the day - I work. What other people think doesn’t bother me.”

Rebuilding

Many people in society – including too many politicians – continue to look down on social housing and, by extension, the people who call it their home

Four decades ago councils were responsible for 40% of new houses. By 2017 that had fallen to just 2%.

Right to buy and the transfer of council properties to housing associations meant a depletion in stock.

Most social housing in England now belongs to housing associations - 2.5 million as opposed to 1.6 million council homes.

But there are still some who believe that councils could play a big role in tackling the housing crisis, just as they did a century ago.

At the tail end of 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May announced that the borrowing cap that had hampered councils from building in large numbers was being lifted.

She said the stigma about council houses was wrong. She regretted the fact that tenants could “feel marginalised and overlooked, and are ashamed to share the fact that their home belongs to a housing association or local authority”.

“On the outside, many people in society - including too many politicians - continue to look down on social housing and, by extension, the people who call it their home.”

The need is obvious.

An Ipsos Mori survey for the Chartered Institute of Housing found 60% of people supported the construction of new social housing in their area.

Not everybody agrees that councils and housing associations should drive a new wave of housebuilding. There are many who think that changing the planning system and reducing bureaucracy would let private builders produce many more houses and flats.

But whatever the solution, what is clear is that in 2019, the UK faces a shortage of houses and a crisis. Just as it did in 1919.

Author: Ashley John-Baptiste

Additional reporting: Lora Jones

Graphics: Debie Loizou & Lilly Huynh

Photography: Phil Coomes

Additional photography: Getty Images, Alamy, PA, Reuters, Manchester Archives & Local Studies

Online production: Ben Milne

Editor: Finlo Rohrer

Publication date: 4 July 2019