Jo Swinson's

bid to transform

the Lib Dems’ fortunes

This piece was first published 22 November 2019 and has been amended since.

By Jonathan Blake

In the early hours of the morning on 8 May 2015, Jo Swinson stood on a makeshift stage in a leisure centre and braced herself for the news that she had lost her seat in Parliament.

She appeared close to tears alongside the other candidates in East Dunbartonshire, as the returning officer delivered the result which saw the SNP’s John Nicolson elected in her place.

The former business minister was one of many Liberal Democrat MPs dismissed by voters after a bruising five years in coalition government with the Conservatives.

Jo Swinson addresses the East Dunbartonshire election count after losing her seat, 2015

Jo Swinson addresses the East Dunbartonshire election count after losing her seat, 2015

Of the 57 Liberal Democrats in Parliament before the 2015 general election, only eight survived.

But for Jo Swinson, the “cruel and punishing night” - as it was described by her party leader Nick Clegg - was made even worse by the fact that her husband suffered the same fate.

Nearly 400 miles south in Wiltshire, Duncan Hames, a Lib Dem MP whom Swinson had married in 2011, had also lost his seat. The couple, in their 30s with a 16-month-old son, found themselves both out of a job overnight.

“It was hard,” Swinson tells me.

“And we needed to spend some time working through what we were going to do.”

But that was not, it seems, the low point of her career. She has since revealed that she had felt worse on the morning after the EU referendum.

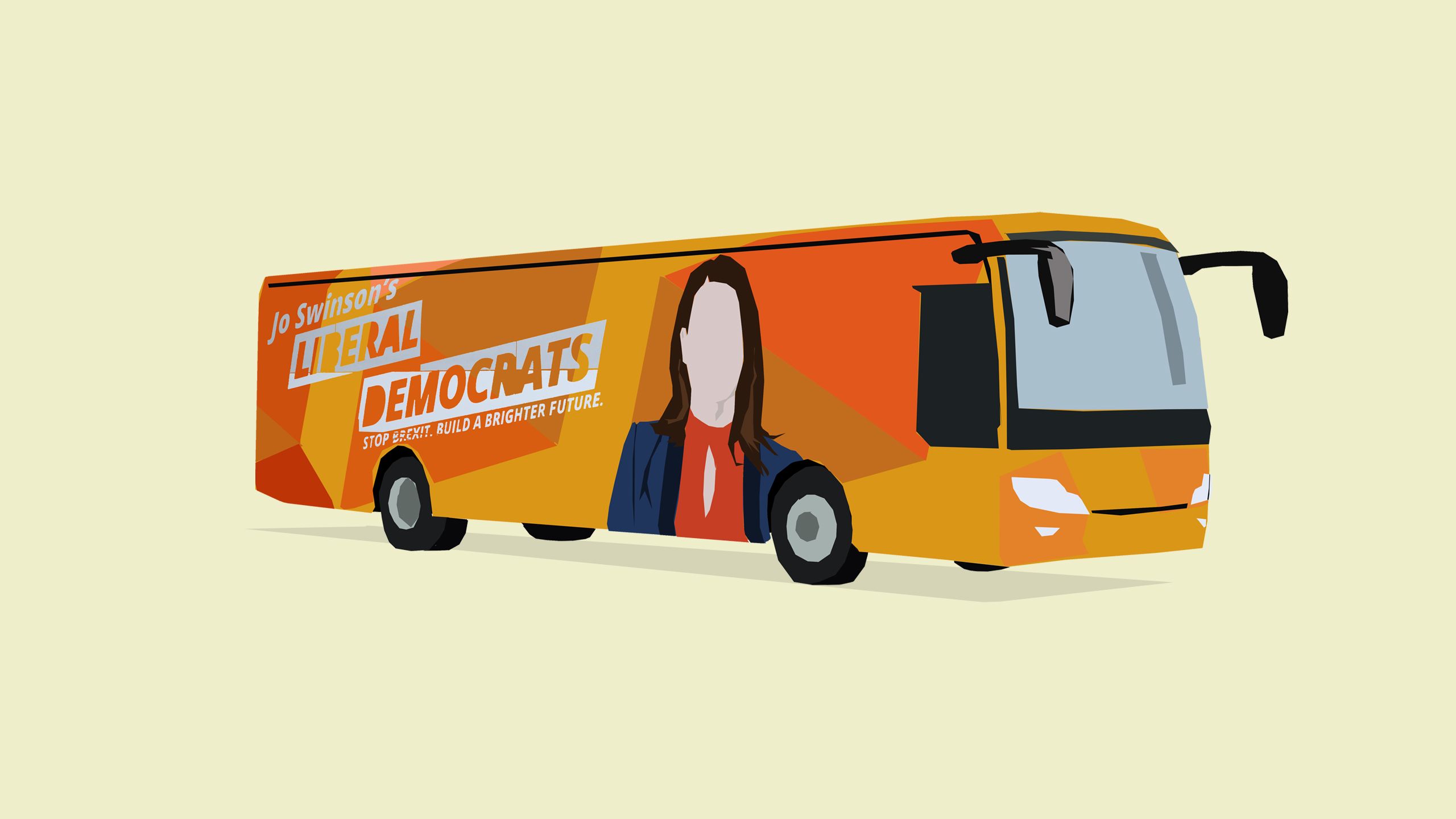

And four years on from losing her seat, having since won it back, Jo Swinson was aboard her election battle bus.

Jo Swinson with reporters on the Lib Dems' 2019 election bus

Jo Swinson with reporters on the Lib Dems' 2019 election bus

On the side was a giant picture of her face, alongside the slogan “Stop Brexit”. This is what she promised to do, should the Lib Dems pull off a political miracle and win a majority.

She had presented herself unashamedly as a candidate for prime minister, and at the end of November was at the very least poised to achieve greater prominence in the most unpredictable election in memory.

Early life

The Take That posters on the young Jo Swinson’s bedroom wall only told half the story.

Yes, she was in many ways a typical teenager who worked at McDonald's at the weekend and went on holiday to Spain with her friends, but as well as swooning over Mark Owen, she showed political instincts from a young age.

At 10 she was writing letters to her MP, and in secondary school mounted a campaign for girls to be allowed to wear trousers. Perhaps either refreshing or grating, depending on your level of cynicism, Swinson claims she has “always wanted to change the world”.

Born in February 1980, Joanne Kate Swinson grew up in the town of Milngavie, north west of Glasgow, the younger of two children.

Her mother Annette was a primary school teacher and her father Pete worked in local economic development. Although her parents weren’t overtly political, their involvement in the local community clearly had an impact. She recalls her dad delivering the Lib Dems’ signature Focus leaflets and encouraging her to “get stuck in and do things”.

“[They were] very much about public service,” she says.

Swinson joined the party she now leads at the age of 17, but there was no intention at that stage to make politics her career. It was 1997 and Tony Blair’s Labour Party had just won a landslide victory.

So why did she choose not to be swept up in that sea change of British politics?

It was, she claims, Paddy Ashdown - the then Lib Dem leader - and his focus on education and changing the electoral system that drew her to the party.

Lib Dem leaders past and present - Tim Farron, Jo Swinson and Paddy Ashdown in 2015

Lib Dem leaders past and present - Tim Farron, Jo Swinson and Paddy Ashdown in 2015

“I grew up on the west of Scotland where it didn’t matter where you looked, it was wall-to-wall Labour MPs.”

Proportional representation, which the Lib Dems have long advocated, seemed “a no-brainer” and encouraged Swinson to join when she went to university.

Politics was still an interest rather than a career but while studying Business Management at the London School of Economics Swinson campaigned for better internet access in student accommodation.

It was another example of her love of technology, having written as a schoolgirl to Smash Hits magazine's Games Corner about cheat codes.

Leader profiles:

It was while she was at university, that she was subjected to a sexual assault, describing later how a man she had thought was her friend had tried to rape her.

In 2018, she wrote that people needed to understand that her experience was “not unusual” and called for better education on consent in schools, colleges and universities.

Swinson graduated with a first class degree. Her first job, which she says she “loved”, was with Viking FM, a commercial radio station in Hull, where she was a marketing manager. But there was clearly something missing.

“It was a fun job to do when I was 21, but it didn’t feel like I was making the world a better place.”

But even then, her decision to run for Parliament in 2001 was not intended to be the start of a political career. Someone, she says, had suggested it would be an interesting experience.

But she was taking on the former Labour deputy leader John Prescott in his rock-solid seat in Hull, and it was, as she puts it, “a seat we weren’t going to win”.

Jo Swinson, election candidate 2001

Jo Swinson, election candidate 2001

There were two more unsuccessful attempts to get elected to the Scottish parliament, in Strathkelvin and Bearsden, before Swinson decided it was all or nothing.

Boundary changes in the seat where Swinson grew up made it possible for a Liberal Democrat to win, something she describes as “serendipity”.

“If I don’t go for this having just decided I wanted to do politics more seriously, I’d always regret it. I went for it 100%.”

Frank Boles, the Liberal Democrats' local party chairman in East Dunbartonshire, was on the receiving end of her determination. “She banged on my door looking for the nomination to be our parliamentary candidate,” he recalls.

There was a “slight intensity” Boles admits that came with Swinson’s confidence. But he says, “she was obviously very sharp considering how young she was at the time.”

On that test of seeking election, she can claim to have more than delivered.

“As a lot of people do at that age, you think the world is yours, but to have actually done it was quite something else,” Franks says, reflecting on Swinson’s boast to have stood in every election in which she has been eligible to vote.

“Baby of the House”

Jo Swinson was elected as Member of Parliament for East Dunbartonshire in 2005, with 42% of votes in her constituency.

As the youngest MP at the time - aged 25 - she was known as the “Baby of the House”. “A rubbish title” in Swinson’s opinion.

Jo Swinson, 2005 election candidate

Jo Swinson, 2005 election candidate

One of the defining moments of her parliamentary career came much later on, when she became the first MP to take a baby into the House of Commons during a debate. She said it “felt natural” as she’d been feeding her three-month-old son Gabriel before needing to go back into the chamber.

At the time, in September 2018, she told the BBC: "The options were: wake him up and hand him to somebody else for 20 minutes, or go in and sit down, do no harm. He stayed asleep for most of it.”

The MP described it as a “step forward for modernising Parliament” and no doubt boosted her credentials as a campaigner for gender equality.

But while she is readily associated with the “gender fight” as she calls it, it is not something she carries as a badge of honour or sees as a guiding force in her political career.

“Like many women in politics when first elected I resisted taking on the gender fight because you get put in a ‘woman box’.

“People tell you that’s all you ever talk about. People say that to me now. It’s not, I talk about lots of things.”

Jo Swinson addresses crowds at the People's Vote March, London, March 2019.

Jo Swinson addresses crowds at the People's Vote March, London, March 2019.

But she admits to being naive about the scale of change needed.

“When I was starting out in politics and in adult life, I thought a lot of those battles had been won.

“Working in politics for the 10 years up to 2015 and in the corridors of power, you realise how much further there is to go.”

And there are examples of where idealism has given way to pragmatism elsewhere in Swinson’s career. Wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan “I am not a token woman” while addressing her party conference in 2001, Swinson’s opposition to all-women shortlists for parliamentary candidates could not have been clearer.

On that she changed her mind, albeit feeling “depressed” at having to do so. And any opposition to tokenism appears to have been completely abandoned. The Lib Dem manifesto for the 2019 election committed to allowing all-BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) and all-LGBT+ shortlists.

That shift in approach to policy mirrors personal changes Swinson has made to her style.

In her early days as an MP, there were some personality issues when dealing with members of her constituency.

“At first, sometimes relationships could be a little brittle, but that was youth,” says Frank Boles, her local party chairman. “She's worked hard on it, and is very much more comfortable with people now.”

In her maiden speech, she addressed a sparsely populated House of Commons with a rehearsed composure that would not have looked out of place in a university debating society.

She spoke of the need to engage young people in politics more, complete with a cringeworthy reference to the fact that it would take more than "baseball caps and text messages".

A well-meaning, if slightly patronising, comment followed from Kelvin Hopkins, the Labour MP for Luton North who congratulated Swinson on a "fine speech" but added "it is something of a surprise when someone many years younger than one's own children is the previous speaker”.

Away from Parliament, Swinson indulged her running hobby and completed the Loch Ness marathon in four hours seven minutes 18 seconds.

Jo Swinson with fellow MPs Stephen Crabb (l) and Edward Timpson (r) training for the 2011 London marathon

Jo Swinson with fellow MPs Stephen Crabb (l) and Edward Timpson (r) training for the 2011 London marathon

She raised money for the anaphylaxis campaign, a cause she is closely associated with, having a severe nut allergy. In 2013, she was taken to hospital where she said doctors “saved her life”.

Although she saw her majority slightly reduced, Swinson was re-elected to Parliament in 2010. She says that after this, she saw a change in attitude from some of her fellow MPs.

“I remember noticing a difference having been re-elected. There’s something about having fought your seat and won it again that commanded a different level of respect.”

With that respect would come the responsibility of government. And with that, uncomfortable compromises and broken promises which live long in the memory for many.

Coalition

government

Soon after being re-elected, the reality hit home to Jo Swinson of exactly what coalition government with the Conservatives would mean for the Liberal Democrats.

“I remember how I felt in the pit of my stomach when I heard what we planned to do,” Swinson told Liberator magazine in June 2019.

The party was about to break its promise not to support any rise in tuition fees for students in England, sparking rebellion and resignations from many in the newly formed coalition.

The plans were passed against a backdrop of protests, as an estimated 50,000 people took to the streets in opposition.

Swinson voted for the policy, though, and looks back on that with regret.

“I’ve learned to trust my gut instinct, and never again fail to challenge a decision that I believed to be wrong.”

At the time, with earnest understatement she described it as “the most challenging issue for Liberal Democrats in the coalition so far”.

“I know that many members will find this difficult,” she wrote on the Lib Dem Voice website, “but I hope it will also be understood that there is no easy answer to the unenviable choices we have to make.”

But Swinson’s repentance did not extend to reversing the decision to raise fees.

The party’s 2019 election manifesto committed to reinstating maintenance grants for the poorest students but promises to “establish a review” of student finance to “consider any necessary reforms”.

Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, and his Lib Dem deputy Nick Clegg, Downing Street, May 2010

Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, and his Lib Dem deputy Nick Clegg, Downing Street, May 2010

Ambition, perhaps, had also clouded her conviction. Swinson served as a junior ministerial aide to the Business Secretary Vince Cable and then Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg.

But her aspirations went beyond that and she took the plunge and asked her party leader for a job in government.

“I made a pitch for myself,” she told the Times earlier this year.

“But over and beyond that, I told [Nick Clegg], ‘I think you should have a woman in the cabinet. It doesn’t have to be me, but it would be a lost opportunity if we had five years in government and none of them were women.’”

Her tactic worked and in 2012, Swinson became under secretary of state for employment relations and postal affairs.

Vince Cable and Jo Swinson leave 10 Downing Street, 2012

Vince Cable and Jo Swinson leave 10 Downing Street, 2012

As business secretary, Cable remembers handing her the “tricky” job of taking responsibility for the Post Office network. She also took responsibility for legislation ensuring changes to shared parental leave and flexible working.

“It was very much her legislation and she made it happen. She was generally a very competent minister,” Cable recalls.

But it is Swinson’s support for the full range of austerity measures instigated by the coalition government that her political opponents continue to draw attention to.

Swinson has since spoken of the party’s need to “own the failures” of the coalition government.

“We lost too many arguments. When they fought dirty, we were too nice,” she told the Lib Dem conference as deputy leader in 2018.

Her voting record bears witness to that.

As a junior minister, Swinson voted consistently for the policy that Labour dubbed the bedroom tax, which reduced housing benefit for social tenants judged to have more bedrooms than necessary.

She also supported a 1% cap on the rise in working age benefits and backed the move to make local councils responsible for providing assistance to those who couldn’t afford their council tax.

Along with austerity measures, Swinson remains associated with economic policies of the coalition.

For example, she voted in favour of cutting the top rate of income tax from 50% to 45% on earnings over £150,000.

A tax cut for higher earners sits in stark contrast to a recent campaign promise to put a penny on the basic rate of income tax to boost spending on the NHS.

Swinson said she regrets voting for some of the austerity measures while in government, but argues the Liberal Democrats were able to prevent even harsher measures being taken.

“With the financial crisis that was unfolding we did need to make cuts. We did need to constrain spending because of the deficit.”

But when the 2015 election came, voters delivered their verdict and Swinson found herself, along with dozens of other Liberal Democrat MPs, ousted from Parliament and out of a job.

Leadership

Sympathy for MPs who find themselves out of a job might be hard to find among the general public but Vince Cable, who knows both Swinson and her husband, said it hit them hard.

“They were potentially out on the streets, not literally but they were in a very difficult position.

“I was really impressed by the personal resilience of being able to manage that situation without going to pieces, and doing it in a practical way and coming out in a good place.”

Swinson compares the experience to the one her father had in his 50s when he was made redundant.

“I remember watching my Dad go through it when I was a teenager… that was really tough.”

The couple’s eldest son Andrew was “a brilliant tonic”, according to Swinson.

“Any thought that you’d sit around and mope, there’s just no way you can do that when you’ve got a 16-month-old who wants to get up and be played with and go to the park and all those things.”

She took the opportunity to write a book, Equal Power: Gender Equality and How to Achieve It, having realised that “it wasn’t a problem that was going to be solved by government on its own”.

But Swinson still felt the pull of politics. In 2017 she jumped at the chance to win back her seat and returned to Parliament.

Jo Swinson with husband Duncan Hames on election night 2017

Jo Swinson with husband Duncan Hames on election night 2017

In a south London pub, one evening not long before the 2019 general election was called, Liberal Democrat MPs gathered for a low-key night out. One who’d recently joined the party reflected that it was the first time she had laughed with colleagues in a very long time.

“It’s the first time I can remember socialising enjoyably with colleagues.”

The group had been for dinner at a pub in Kennington, “nothing very fancy”, the MP says, but credits Swinson with recognising the importance of morale.

“She sees the value in the fact we should be doing that.”

Although she admits thinking a long time ago about whether she could lead the party, deciding to go for it was something Swinson did not set her sights on early.

“It crept up on me,” she says.

When her predecessor first announced his intention to stand down towards the end of 2018, Swinson’s second child was two months old.

“At which time I was mainly thinking about whether I’d be able to make and finish drinking a cold cup of tea,” she adds.

Tim Farron, another former leader, told her she’d lead the party one day but “properly deciding to absolutely go for it” didn’t happen until the beginning of 2019.

In July this year, Jo Swinson was elected as leader of the Liberal Democrats, winning 47,997 votes to her opponent, Sir Ed Davey’s 28,021.

Notwithstanding the after-work drinks and friendly WhatsApp messages to colleagues, there is an uncompromising side to her leadership.

“Authority is her thing,” one parliamentary colleague said.

“If necessary being very firm with people who aren’t toeing the line or not up to the job.

“In terms of how she manages staff, if they're not up to the job they go. She’s got very high standards and is tough in enforcing them.”

The Lib Dems’ party culture is such that very little happens without the say-so of grass-roots members and policy decisions are often taken by committee.

There were raised eyebrows and rumblings of discontent, when it was announced at the 2019 conference that the party would campaign to revoke Article 50 - which sets out the process for a country to leave the EU - without a further referendum if it won a majority.

Although the outcome seemed highly unlikely, at least one senior party figure felt it hadn’t been properly consulted on and risked sending the wrong message to supporters.

Jo Swinson speaking at an election rally, November 2019

Jo Swinson speaking at an election rally, November 2019

There is an eye for detail which can be a frustration for those working closely with Swinson.

Frank Boles is used to constituency leaflets coming back marked “with a classic purple pen”.

“Bits of paper don’t go out until she’s had a chance to scrawl all over them and rewrite them.

“Sometimes you’ll say, ‘Back off Jo, we’ll write these for you, you’ve got other things to do.’”

Recently, Swinson denied losing control of her party after a candidate in a marginal seat stood aside to avoid splitting the remain-supporting vote and handing it to the Conservatives. Tim Walker withdrew from the race in Canterbury but the party announced he would be replaced.

Jo Swinson said there had been “a healthy debate” in the party leading to some candidates deciding to stand aside.

But the episode demonstrated the risk of Swinson’s strategy to fight Labour head-on and set the Lib Dems apart as the only truly UK-wide Remain party.

As the leader of a party defending just 19 seats, declaring yourself a candidate to run the country attracted a level of derision and ridicule.

But her predecessor did the same, and maintained that it was the only option if Swinson wanted to be taken seriously.

“It's a very long shot but it's a totally legitimate ambition and if you didn't have it people would wonder what the hell are we there for,” Sir Vince Cable said.

Swinson did admit that it would be “a big step” for the Liberal Democrats to win a majority, which was nothing if not an understatement.

Having inherited a party in good shape and welcomed MPs from other parties keen to ride the Lib Dems’ anti-Brexit wave, expectations among the party’s supporters were enormous.

Asked if she had thought about winning, and seeing herself in No 10, Swinson laughed.

“Yeah, but I don’t think about the last bit because I’m not sure I like the idea of moving.”

It was a long way from East Dunbartonshire to Downing Street after all.

Credits

Author: Jonathan Blake

Online production: Paul Kerley

Illustrations: Emma Lynch

Photos: PA Media, Getty Images, Alamy, Phil Coomes, Roberto Cavieres

Additional research: Laurence Sleator

Editor: Kathryn Westcott