Ballymurphy:

‘Entirely innocent’

What happened in 1971?

In the space of 36 hours in August 1971, 10 people were shot dead on the streets of Belfast during an army operation.

Among them were a 44-year-old mother-of-eight, a former soldier who had lost his hand in the Second World War and a Catholic priest who had come to the aid of an injured man.

Their deaths, which took place in and around the Ballymurphy area in the west of the city in five separate incidents, have been cloaked in controversy in the decades since.

A number of the victims were portrayed as gunmen in the aftermath of the deaths. The Army maintained that soldiers fired only after perceiving that they were under threat.

Their families rejected this, maintaining that their loved ones were unarmed innocent civilians. One-day inquests into the deaths in 1972 recorded open verdicts.

In 2011, Northern Ireland’s attorney general ordered a fresh inquest into the deaths. It began in September 2018 and, after more than a year of hearings and another year-long delay due to Covid-19, the coroner has delivered her verdict.

Mrs Justice Siobhan Keegan found that the 10 people killed were "entirely innocent of any wrongdoing". She said nine of the 10 were killed by the Army, while she was unable to determine who killed the 10th victim - John McKerr - in large part because of the "abject failing" of authorities to investigate at the time.

The coroner found that in some of the incidents, the threat against the Army justified soldiers opening fire, but the use of lethal force was disproportionate.

This is the story of the people who died and how their families have waged a 50-year campaign to clear their names.

The Ballymurphy shootings took place in west Belfast, but it was the spiralling sectarian conflict on streets across Northern Ireland that set the course for what happened in August 1971.

The Troubles had begun two years earlier, with violence continuing to escalate in the first half of 1971, particularly in the cities of Belfast and Londonderry. Northern Ireland’s Prime Minister Brian Faulkner was under pressure to take a tougher stance on paramilitaries, particularly the IRA.

The Stormont government ordered a crackdown which meant anyone who was suspected of being involved in violence could be detained without trial – or interned. Operation Demetrius was the military-backed operation that saw 342 people detained across Northern Ireland on 9 August.

But instead of stopping violence, internment only provoked it. In the four days of turmoil that followed, 25 people would die on the streets of Belfast. Thousands would flee their homes as whole areas were destroyed. While 30 people had lost their lives in 1971 before the introduction of internment, by the end of the year 141 would be killed.

The first Ballymurphy shootings took place in Springfield Park, where the ground rises to the hills overlooking Belfast.

In the early 1960s, before the Troubles began, the new development was considered by some to be a blueprint for Northern Ireland’s future.

Its modern homes – with three bedrooms, indoor plumbing, electricity, gardens front and back – were snapped up by young families and couples from both Catholic and Protestant communities, a dream opportunity for people accustomed to terraced houses with no mod cons.

Springfield Park wasn’t planned as an idyll of integration, it merely happened, because families were buying the best houses they could afford.

But on 9 August, rioting engulfed Springfield Park and the surrounding area when soldiers moved in as part of Operation Demetrius.

Internment lit the touch-paper on growing tensions in the Springfield Park area. While residents had continued to live in harmony in the street itself, they had been feeling the sectarian squeeze from the mainly Protestant Springmartin estate to the north and east and the Moyard and Ballymurphy, Catholic areas, to the south and west.

One resident later told documentary-makers Frank Martin and Seamus Kelters in ‘A million bricks’ that that Springfield Park was the “jam in the sandwich”.

It was a community that had been transcending the usual tribal boundaries. But as Bobby Clarke, a man wounded on 9 August, told the same documentary, “one night destroyed it”.

Incident One :

The Waste Ground

The rioting and sectarian violence of August 1971 formed the backdrop for the bloodshed at Ballymurphy.

At the inquest, residents, backed by evidence from soldiers and police officers, spoke of attacks coming from the Springmartin estate by an angry crowd determined to make them leave their homes.

Springfield Park

Springfield Park

As the clear August evening drew on, rival crowds gathered, facing each other from Springmartin Road and Springfield Park.

That's when the gunfire started.

Gerry McCaffrey, a Springfield Park resident and footballer, was carrying his young daughter from his home when he was shot in the back with a shotgun.

Soldiers from the Parachute Regiment and Queen's Regiment were there in numbers too. The air soon rang out with the crack and thump of their self-loading rifles (SLRs).

The inquest heard evidence that IRA members had fired handguns in the area and there were also claims that a sniper from the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force had shot at some of the victims. The coroner accepted that there was "at least a small presence" of gunmen in the area at the time of the incident.

It was at this point that frantic families on Springfield Park, trying to leave the area, were faced with a choice – stay or escape across the exposed area of waste ground.

Father Hugh Mullan

Father Hugh Mullan

Father Hugh Mullan, 38, who lived directly opposite the waste ground, heard the gunshots ring out and was making phone calls to local army commanders he knew, pleading with them to stop the soldiers from firing.

Bobby Clarke, whose house was also near the waste ground, was among the first to take action. He ran across the open ground with a child, aiming for safety in Moyard Park. As he ran back towards his home, he was shot in the back and fell to the ground. He was unarmed.

People ran to his aid, including Fr Mullan, who rushed to administer the last rites. Frank Quinn, 19, ran over to help too. Bobby told the inquest he wasn’t dying and rejected the rites, but Fr Mullan proceeded anyway as they “would give them strength”.

Speaking in 1999, Bobby Clarke said that Fr Mullan then left him to ring for an ambulance.

“He went out with this lad towards the phone, the lad was upright, Fr Mullan was down on one knee with a white hanky. He went 20, 30 yards and there was a burst of gunfire and a scream.

"The screams got lower, I would say within 15 minutes there was no more sound. I reckon he was dead at that time.”

Bobby Clarke remained prone in the dirt as gunfire continued to erupt around him.

A cross marks the spot where Fr Mullan died

A cross marks the spot where Fr Mullan died

“I don’t think it’s any exaggeration to say the very ground we were lying on was trembling with bullets that were flying about, coming at us.

“A lad beside me who had put a shirt on my back jerked up in the air and down again – I knew from the expression on his face that lad was dead. Turned out to be a lad called Frank Quinn.”

Frank Quinn

Frank Quinn

Mr Quinn, a husband and a father, worked as a window cleaner. Those who knew him described him fondly as a practical joker.

The loss of Fr Mullan, who had pleaded for an end to the hostilities in the hours before he died, a priest who was well-known and liked among those who knew him in the Army, brought shock and grief to his parishioners and the wider community.

Most of the people who fled their homes in Springfield Park on 9 August 1971 never returned. Over the next two days, there would be four more shooting incidents in the area.

Ten people died and with them the dream of Northern Ireland’s blueprint community.

The coroner said Frank Quinn and Fr Mullan were shot by the Army. Mrs Justice Keegan found neither were armed; acting in any way that posed a threat; that the state had not justified their shooting and that the use of force was disproportionate. She also said there was no proper investigation into their deaths.

Fr Mullan loved the sea. It was in his family’s blood, from his grandfather onwards. Growing up in his home town of Portaferry, County Down – on the shores of Strangford Lough – he used to go out sailing. Before he was called to the priesthood, he spent a year in the Merchant Navy.

His grave is in a small cemetery in the town, where you can smell the Irish Sea blowing through the headstones. Here in the graveyard of St Patrick’s Church, the headstone pays simple tribute: “Hugh Mullan, Priest. Died serving his people in Ballymurphy.”

It’s a reminder of Fr Mullan’s other love – people.

“He was there to help people, to help people help themselves,” said Patsy Mullan, his brother. “That was the way he worked.”

Patsy is here in the cemetery, with Geraldine McGrattan, Fr Mullan’s niece and goddaughter. He remembers his older brother Hugh as the person with whom he shared a room and a bed growing up; the one who had plenty of friends; who loved to swim every day and worked hard in school, and in life.

Patsy Mullan and Geraldine McGrattan

Patsy Mullan and Geraldine McGrattan

For Geraldine, he was simply Uncle Hughey. She remembers his voice: “My mother and him loved to sing. He played the guitar, my mother sang, my father provided the words of the song if they forgot it – it was always good fun."

The family have been waiting five long decades for the truth about what happened to Fr Mullan.

Patsy remembers his mother getting a call, at about 3pm that August day, from her son Hugh telling her not to come visit him as things were not good in the area.

He told the inquest he then spent the day listening to news bulletins, which later reported a priest had been shot in Ballymurphy. He knew it was his brother, because he felt sure Fr Mullan “would be out and among people, because that’s the type of person he was”.

Geraldine remembers how she raced home from a holiday in County Kerry, on the other side of Ireland, stopping only for newspapers and at an army checkpoint on the border.

“At the time, there was very little information coming through, but we knew he had been shot, we knew he had gone to give the last rites to an injured man, a man who had been shot and others thought was dying, and that seemed perfectly logical, that was what he would’ve done – he would’ve gone immediately without consideration for himself, he would’ve gone to help someone.”

During the inquest, Bobby Clarke spoke about the guilt he carried for almost 50 years: “I hold myself responsible for the deaths of two people.”

Patsy said Bobby was the only person to visit the Mullan family after his brother’s death. In the aftermath of the Ballymurphy shootings, the Army branded the victims as gunmen in media reports, but Bobby told the family what the inquest would later find to be true almost 50 years later - that Fr Mullan came to his aid.

“The info we were getting is [that] ‘he was a gunman’, ‘he was involved with other people’, ‘he had guns’, ‘he shot himself at the same time as the other boys were shot’ – it wasn’t true,” said Patsy.

The family even presented the inquest with evidence demonstrating the high regard in which Fr Mullan was held by the Army.

Ten days after his death, Lt Col Peter Chiswell, officer commanding of the 3rd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment (3 Para), wrote to Bishop William Philbin.

The battalion was not in Ballymurphy during the shootings, but had been there for more than four months previously.

In the letter, Lt Col Chiswell expressed “the sympathies of every officer and parachute soldier in the 3rd Battalion”.

He said the soldiers knew Fr Mullan as a “fine Christian man” and also as “a priest to whom we could go to for help, advice, guidance and encouragement”.

Fr Mullan had “won our respect”, he said. He had formed a “bond of friendship” with the soldiers.

Another letter to Bishop Philbin, from Lieutenant General Sir Harry Tuzo, then general commanding officer in Northern Ireland, said Fr Mullan's "standing within those Army units which had served in the west of the city was of the highest".

For Geraldine and other family members, what was reported about Uncle Hughey in some quarters – that he had handled or used weapons – calcified into an ever-growing anger, as almost five decades elapsed without the truth.

The truth finally emerged when Mrs Justice Keegan said that Fr Mullan was a "peacemaker", who was shot and killed when he went to help an injured man while carrying a "white object", possibly a T-shirt or handkerchief.

"There is clearly enough evidence that Fr Mullan was going to the field to help an injured person and that he was shot twice in the back," she found.

Mrs Justice Keegan added that there had been "absolute silence" on his death from military witnesses, which she found "surprising" and noted that if the Army could pinpoint gunmen in the field, as was testified, then she could not understand why they could not see Fr Mullan coming into the waste ground when it was still daylight.

His death, and the suggestion that he was not innocent, was a tough pain, Patsy said, which did not subside over the 50 years that has followed.

“There’s very few days that go by that you don’t think about him and it got worse actually, when this court case came about. I’ve been to sea, I’ve been on a bridge of a ship and I would sing a bit and I would sing his songs and cry as I sung them because he loved to sing…” said Patsy, tears emerging now as then.

“You would miss him for all that type of thing. The type of thing you used to do when they were at home.”

Incident Two :

The Manse

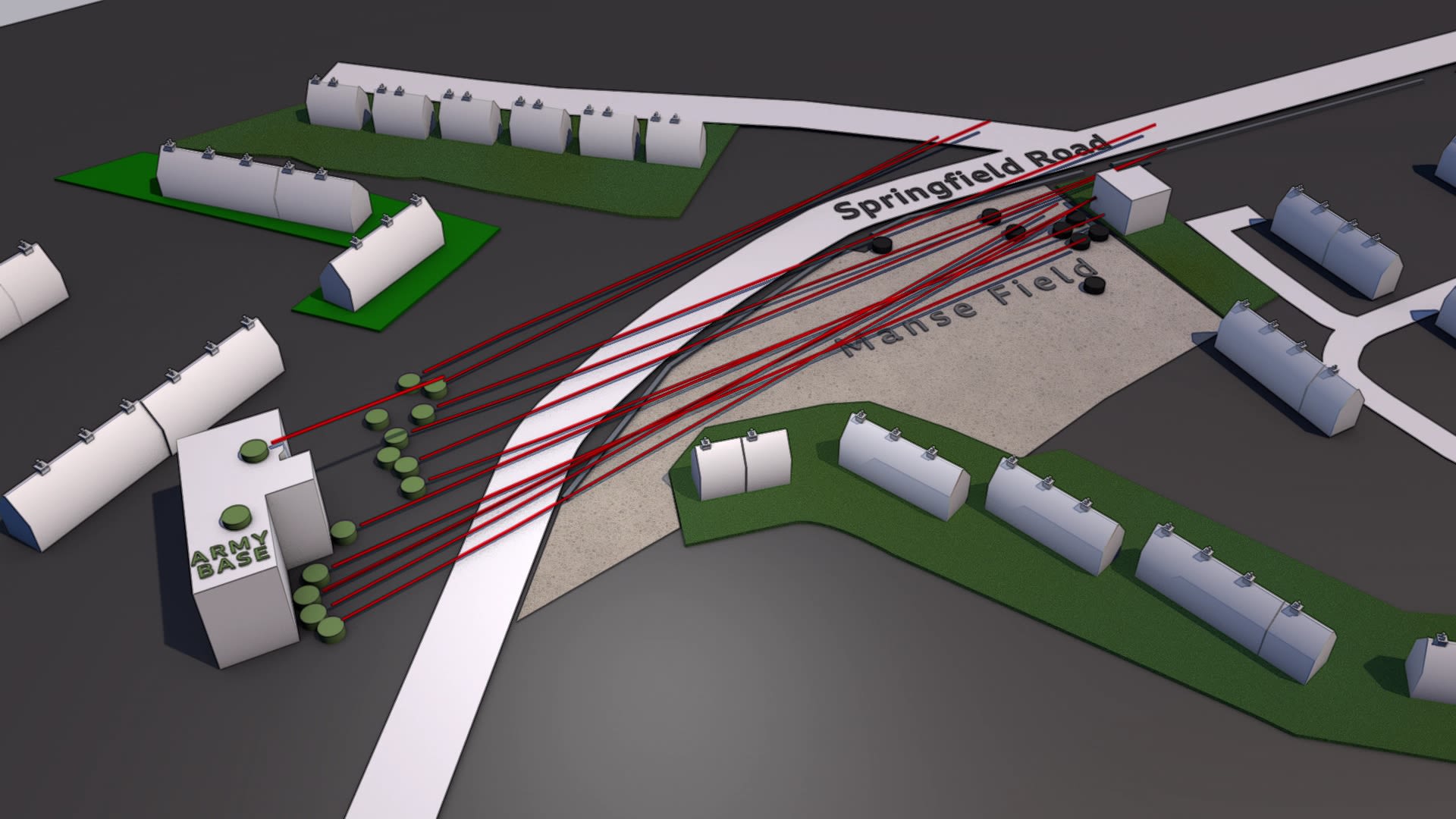

Minutes after the deaths of Fr Mullan and Frank Quinn, four people were shot dead on an expanse of open ground opposite an army base sited within two buildings, the Henry Taggart Memorial Hall and Vere Foster School.

The open ground had previously been used as a manse for a local church. The base had been used for internment arrest operations on the day, leading to demonstrations and rioting outside.

Image shows the trajectory of shots fired by soldiers from the Army base

Image shows the trajectory of shots fired by soldiers from the Army base

Shooting broke out from the base, scattering the crowd. Soldiers testified to the inquiry that they had opened fire in response to shots being fired at the base. The coroner said she did not believe there was "sustained shooting" but that there may have been sporadic gunfire, and that those in the Henry Taggart Memorial Hall would "viably think they were under attack by the community".

She said she was satisfied there was some IRA activity in the area, and evidence that they shot at the Army, but that there was no evidence to link those who were killed with that activity. The coroner added that the shooting of an 11-year-old child, Eddie Butler, in the manse field illustrated the extent of the unjustified response.

Some of those who died were running across the field when they were hit, others were taking shelter behind gate pillars or in a ditch.

Joan Connolly, a 44-year-old mother-of-eight, had gone out to look for her daughters when she was shot and killed by the Army.

Joan Connolly

Joan Connolly

An eyewitness who lived beside the manse area - Margaret Elmore - told the inquest about shots hitting the gable wall of her home. She said she looked out her mother's bedroom and saw a man and woman hunched over behind a bush with their backs to her.

She said Mrs Connolly went to get up and she thumped on the window to tell her to stay down. Ms Elmore said she heard the man say, "for God's sake, get down".

She didn't see the shot but she saw Mrs Connolly turn and say, "mister I can't see". The witness said the shot had removed most of her face.

Another witness, Agnes Keenan, said she saw Mrs Connolly later being lifted and tossed into the back of an armoured vehicle “like a sack of potatoes”. The inquest noted that Mrs Connolly was not transported to the Henry Taggart Hall "with the greatest measure of diligence or respect".

Mrs Connolly's daughter, Briege Voyle, found out about her mother’s death after she was moved to a refugee camp in County Waterford, in the Republic of Ireland, about 500 miles from Belfast in Northern Ireland.

She testified that her mother had welcomed the Army's arrival in Northern Ireland, seeing troops as protection, and had provided them tea and sandwiches. Her final words to Briege were a warning not to go into Springfield Park “because the Protestants would shoot you, the Army won’t”. Briege said her mother’s death “destroyed” the family.

The Army claimed at the time that she had been handling a gun. Briege said: “Whilst coping without her has been hard for all of us, what has made things worse were the media reports that she was a gunwoman and the rumours that followed us, that we were the children of the gunwoman that was shot. I believe this to be untrue.”

The inquest found that Mrs Connolly was unarmed; that she was not acting in any way that posed a threat; that the state had not justified her shooting and that the use of force disproportionate. It also found no proper investigation into her death was ever carried out.

Daniel Teggart, 44, was a father of 10. His family said he was in the area in an effort to help his brother Gerald’s family leave the Springfield Park. His injuries suggested he was shot as many as 14 times and was then taken into the Army base, where he died.

Daniel Teggart

Daniel Teggart

His daughter, Alice Harper, told the inquest she went to the base three times to try to find her father, asking soldiers if he had been arrested. She told the inquest soldiers in the area sang "where's your papa gone?" when she inquired about him. She said some journalists took her to the morgue where she viewed her father’s body. “After that, all of our lives changed completely.”

A deposition of Soldier N given in 1972 stated that 38 rounds of ammunition were found in the pockets of Mr Teggart. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) argued that there was evidence he possessed that ammunition at the time he was brought into the base.

However, the coroner said she was not satisfied "this fact is proven", saying she could not understand why there was no further examination of the rounds that would have connected them to Mr Teggart. She noted that the ammunition was not mentioned by any other witnesses in the base despite it being a substantial amount.

The inquest found that he was unarmed; that he was not acting in any way that posed a threat; that the state had not justified his shooting and that the use of force was disproportionate. It also found no proper investigation into his death was ever carried out.

Noel Phillips, a 19-year-old window cleaner, died after being shot in the neck and limbs, causing fatal blood loss.

Noel Phillips

Noel Phillips

His brother Kevin, who described him as “so easy going no one could say a bad word about him”, said Noel was “doing what kids do” and went for a “nosey” when trouble broke out around the base.

His brother Robert and a brother-in-law went to the morgue that night to identify Noel’s body. His death would send his mother “to pieces”, the family said.

The inquest found that he was unarmed; that he was not acting in any way that posed a threat; that the state had not justified his shooting and that the use of force was disproportionate. It also found no proper investigation into his death was ever carried out.

Joseph Murphy, a 41-year-old father-of-12 was shot in the right leg. He was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital where he was operated on. Eleven days later, his right leg was amputated.

Joseph Murphy

Joseph Murphy

However, two days later, on the birthday of his twin sons, he died in intensive care with the cause of death recorded as septicaemia due to a gunshot wound. His daughter Janet Donnelly said: “This was the first time I ever saw my brothers cry. They never celebrated another birthday since that day.”

She told the inquest she remembered standing in a black dress in the family’s garden on the day of the funeral. Soldiers were singing "where's your papa gone?", she said.

In 2014, Mr Murphy’s body was exhumed at the request of his family, who believed a bullet would be found inside his remains. They said their father maintained he was shot again after being taken into the base. The exhumation led to the discovery of a military-issue bullet, which the family believed proved their father's account.

Mrs Justice Keegan said the expert evidence did not support the case that he was shot in the hall, but found he was "handled with some insensitivity" by soldiers and that his "family were also badly treated". She added that she believed "some personnel were triumphalist and abusive towards the able bodied that were brought in, including by means of physical abuse".

The inquest found that he was unarmed; that he was not acting in any way that posed a threat; that the state had not justified his shooting and that the use of force was disproportionate. It also found no proper investigation into his death was ever carried out.

Incident Three:

The Barricade

The third shooting incident took place the next day – 10 August 1971 – and led to the death of Eddie Doherty, 31, who himself was a former Territorial Army soldier.

Eddie Doherty

Eddie Doherty

The married father-of-four was shot by the only soldier who admitted to the inquest that they had killed someone.

Following the carnage of the day before, many of Belfast’s streets had been barricaded. One barricade was formed on the Whiterock Road, on the edge of the Ballymurphy estate.

The soldier, who was given the cipher M3, gave a TV interview at the time. He later told the inquest his vehicle came under attack after he was ordered to clear the barricade using a military tractor. He described an explosion of some kind, which buckled the wheel of the vehicle. He said he kicked open the cab door and fired at a man who had thrown a petrol bomb at him and was preparing to throw another.

Soldiers travel in convoy on the Whiterock Road

Soldiers travel in convoy on the Whiterock Road

Eyewitnesses testified Mr Doherty was not from the area and was standing 30 yards from the barricade, asking if anyone could help him find a new route so he could get home.

The pathologist who examined his body told the inquest there was no smell of petrol on the body, which could be expected of an individual who had been handling petrol bombs.

The family testified that during his funeral, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) lined the road and saluted him as the coffin passed.

His sister, Kathleen McCarry, said he was a family man who had sent his wife and children to County Down when rumours about internment began to spread. She said her family was torn apart by grief. “My mummy went to pieces, we all went to pieces, it was like a nightmare you were never wakening from.”

The inquest found Soldier M3 was under threat from a petrol bomber and, as a result, was in fear of his life. The coroner said he was justified in taking action against the petrol bomber. However, Mr Doherty was not the petrol bomber and was not acting in a manner that could be perceived as a threat or justify a violent attack on him. The coroner said the soldier's firing of his weapon was not sufficiently controlled for a number of reasons, including that he did not issue a warning.

Incident Four:

The Mountain Road

John Laverty, 20, and Joseph Corr, 43, were killed on the morning of 11 August, 1971 by the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (1 Para).

On this August morning, members of the regiment were making their way to the edge of Ballymurphy via a small, country backroad known as the Mountain Loney or Mountain Road.

Eyewitnesses told the inquest there were concerns, heightened by the tension of the previous days, that loyalist gangs from the Protestant community would attempt a sectarian attack on the Catholic area from the same route. Residents were on the alert for anyone who would try to come into Ballymurphy from the Mountain Road. Some said it never occurred to them that the Army would try to come into the area by force.

Witnesses testified that residents were alerted to the early-morning approach by the banging of bin lids, a common signal used in Northern Ireland’s Catholic communities to alert residents to an incoming threat. Word got around that an attack was happening and some men had gathered, ready to run up the road to defend their area. But instead of loyalists, they met paratroopers.

The soldiers opened fire – Mr Laverty died at the scene; Mr Corr was shot in the chest and died two weeks later in hospital.

John Laverty

John Laverty

Mr Laverty’s youngest sister, Carmel Quinn, said he was a “young fella that had so much life in him to live”. She said her sister Rita recalled their father “cry out in the chapel, ‘ah God, my son’ and breaking down” following his death. “We’d never seen our daddy cry before,” she said.

The family of Mr Corr was in the process of emigrating to Australia when he was killed. His daughter, Eileen McKeown, said his death devastated her family. “The soldiers who did this, they don’t realise the after-effects. I mean, I used to have four brothers and now I’ve none.

"With all the boys, they resented the fact that they lost their daddy and they never had a father figure around. Their dependence on alcohol and early deaths are a direct result of losing my daddy.”

Joseph Corr

Joseph Corr

Mr Corr worked for the manufacturer Shorts as a machinist. It was one of Belfast's biggest employers and the vast majority of its workforce was Protestant. After being labelled as an IRA gunman following his death, the Corr family said they received hate mail from former co-workers.

Journalists at the time were told 1 Para had killed two IRA gunmen by an army captain assigned to press relations.

The inquest found there was no evidence either Mr Corr or Mr Laverty were armed or acting in a manner that could be perceived as posing as a threat. It found no valid justification had been provided for the soldiers opening fire and the circumstances of their death was not adequately investigated.

Incident Five:

The Church

The final death took place later on 11 August.

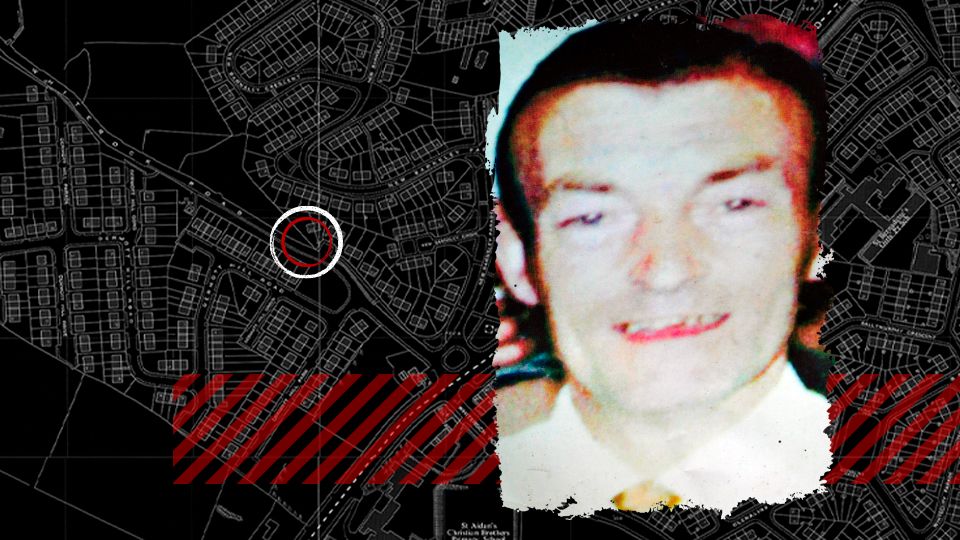

John McKerr, 49, was a joiner and former British soldier who lost his right hand during World War Two in North Africa. On that August day, the father-of-eight and grandfather-of-four was sent to the newly completed Corpus Christi Catholic Church to work through a snag list of defects.

John McKerr

John McKerr

The church was also preparing for the funeral of a local teenager, who had accidentally drowned two days earlier. Mr McKerr was outside the building when he was shot behind the right ear, the bullet exiting his head further forward. He died in hospital nine days later.

Some witnesses told the inquest they heard an officer tell a paratrooper to shoot him.

Corpus Christi Catholic Church

Corpus Christi Catholic Church

Some described soldiers pointing in Mr McKerr’s direction, perhaps mistaking his prosthetic lower arm for a weapon.

The inquest heard evidence from Maureen Heath that she was one of those to rush to Mr McKerr’s aid. Before her death, she told researchers that after cradling him, a paratrooper pointed a gun at her and threatened to shoot.

Mrs Heath, a friend of Fr Mullan, said she told them: “Go ahead and shoot.” She added: “They’d shot our priest, so what was my life worth?”

Mr McKerr's family found out he had been shot from an inaccurate newspaper report the day after it happened. His eldest daughter, Anne Ferguson, said one newspaper report said Mr McKerr had been attending an IRA funeral when he was shot, a detail that was particularly upsetting for his family. She said reports “about daddy being in the IRA were terrible lies which only made matters worse".

Mrs Ferguson added that her mother "was very practical and when my father died his war pension stopped and she was struggling to bring the family up so she did not pursue an investigation".

The inquest said Mr McKerr was not doing anything that could have caused someone to think of him as a threat or which justified the use of lethal force. It found he was clearly unarmed.

However, the coroner said she could not determine who had shot Mr McKerr. She said it was "shocking that there was no real investigation" into his death at the time. There were no military statements taken, the scene was not sealed and the bullet went unrecovered.

She described this as "an abject failing by the authorities" that had hampered her greatly and that it was the "striking feature of this case that I record in the strongest possible terms".

The Campaign

In 1972, seven inquests were held into the deaths of the 10 victims. Each one recorded an open verdict, which meant it did not specify the cause of the deaths. The outcome was rejected by families who considered it a whitewash.

Their anger was compounded by the lingering perception that the victims were IRA members, fuelled by the media reports from the time quoting Army sources.

The decades passed and the IRA and loyalist ceasefires of 1994 paved the way for the Good Friday Agreement, which was supported north and south of the border.

However, if the rest of society was looking forward, many people left bereaved by the conflict could not leave the past behind.

Among them were the Ballymurphy families, who even 27 years after the event did not fully realise the extent of the connection between them.

On an August evening in 1998, four months after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the assembly hall at St Mary’s University in west Belfast was full.

A couple of hundred people had claimed chairs on the main floor while more still, who arrived too late to get a seat, lined the sides and back of the hall.

The audience for the event – the Forgotten Victims Conference, organised by campaign group Relatives for Justice - were from all corners of Northern Ireland and they were attending to speak about their experiences with the the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Army.

Among them were Janet Donnelly, the daughter of Joseph Murphy; Carmel Quinn, the sister of John Laverty; Alice Harper, the daughter of Danny Teggart; and other family members of those killed at Ballymurphy.

After a number of pre-arranged speakers stood to tell their story, the floor opened up and a roving microphone was passed around. Liam Quinn spoke about his brother, Frank; next it was Janet Donnelly; then Alice Harper.

Later Pat Connolly, the son of Joan Connolly, and Maureen McKerr, John McKerr’s wife, joined the growing chorus of Ballymurphy voices.

Carmel Quinn was standing at the back of the hall with her husband. The trauma of her brother’s death had splintered through her family for generations. Her mother was “never the same”, her father died a “premature death” at 61.

“The only thing that got mummy through was her faith," Carmel said. "She went to chapel every single night. I used to go to chapel with my mummy, but maybe that’s put me off – I’m not a chapel goer.”

For years, Carmel's pain had been locked tight within her and the walls of her family’s home – but now, standing in the assembly hall, she was beginning to realise that her trauma was shared far wider than she previously could have guessed.

“I was aware of Janet, because I went to school with her, and the Connollys and Teggarts – but the likes of the Quinns, Mr McKerr, we didn’t know anything about them. In that hall, that’s when it seemed to all become relevant – my husband said to me: ‘That’s all the same incident – that’s the one incident.”

That night would be the catalyst for what family members would later call the Ballymurphy Massacre campaign, a movement of bereaved relatives who would band together to investigate exactly what happened to their loved ones with the aim of securing a fresh investigation into their deaths.

Paddy McCarthy

Paddy McCarthy

Their campaign would centre on the deaths of 11 people – the 10 shooting victims and Paddy McCarthy, who suffered a fatal heart attack after an alleged violent confrontation with soldiers.

The families started with the paper trail. Some of them had already begun individually seeking all the documentation they could from the original inquests, but, now that they were aware of each other and could work in a co-ordinated way, they started to make more progress in what was often a bewildering process.

Janet Donnelly recalls receiving 10 pages relating to her father’s inquest - but noting that one of the pages was numbered 99.

“That was the first time I found out it was one inquest that looked at the deaths of four people,” she said. With communication now open between the families, she was able to sign a joint letter with relatives of Danny Teggart, Joan Connolly and Noel Phillips to get the complete set of documents.

The next step was knocking on doors across Ballymurphy in an effort to find eyewitnesses.

Over the next few years they spoke to about 130 people who helped to piece together the events of August 1971. The process took its toll both on the families seeking answers and those providing them, who in many instances had not previously spoken about what they had witnessed.

“They never had spoken to anybody, they had never got any counselling for what they had seen,” said John Teggart, Danny Teggart’s son and the brother of Alice Harper. “It was a shock to them and you could see that they were reliving it in their head and that’s how you knew they were genuine.

“They would stand back, quiet – and then all of a sudden say: ‘I was never asked…’

This silent trauma hit even closer to home for Janet Donnelly, who found a new witness in her own family – her brother-in-law.

“He was married to my sister for 20 years and saw my father being shot. Until we started doing this, I didn’t know,” she said.

“I know it was brought up a few times in the coroner’s courtroom: ‘Why didn’t you talk about it?’ But people literally didn’t talk about it. And, when they did tell you their story for the first time, they relived it.”

By this stage, campaigners were juggling work, family life and evidence gathering. They began meeting every Monday night in Springhill Community House to co-ordinate their efforts.

John Teggart and Janet Donnelly

John Teggart and Janet Donnelly

John Teggart joked about the thousands of miles he put in driving a blue Toyota Corolla dubbed the “campaign car”.

Carmel Quinn, meanwhile, remembered making her children lunch while on the phone chasing obscure documents from the public records office and pushing her son in a pram while going door-to-door seeking information. There were plenty of sleepless nights, when her mind “ticked over and over and over” – but the “drive to get to the truth” never wavered.

Carmel’s last memory of her brother John was of him smiling and waving her onto a bus that would take her to safety at an Irish Army Camp in the Republic of Ireland. She was eight years old when he was killed.

“I know things can change in a blink of an eye, so quickly. Because my life went from that eight year old who knew nothing but happiness to just… our house was never the same.”

She added: “I’m not eight anymore. If my brother hasn’t got me or my sister to tell people what happened, who had he got?”

For several years the campaigners steadily built their case, until it came to the point that, according to John Teggart, they had gathered “everything we needed – but we didn’t know what to do with it”.

In Derry, the relatives of the 13 people shot dead during Bloody Sunday were in the midst of the Saville Inquiry, a new public investigation into what had happened on 30 January 1972, which began in 2000.

Thirteen people were killed after members of the Army's Parachute Regiment opened fire on civil rights demonstrators in the Bogside.

Thirteen people were killed after members of the Army's Parachute Regiment opened fire on civil rights demonstrators in the Bogside.

There were some unsettling connections between Bloody Sunday and what happened six months previously in Ballymurphy, not least that the 1st battalion of the Parachute Regiment – 1 Para – was at the centre of both. But the progress of the Bloody Sunday families gave the Ballymurphy campaigners hope, as well as an added network of support and advice.

Still there was some reluctance to raise the profile of their campaign.

“Them days you didn’t raise your head above the parapet,” John added. “You would be a bit scared back then – so it took us a couple of years to take the next step of going public.”

In 2007, the families officially launched their campaign seeking a new investigation into the deaths of 11 people.

Over the next few years, their work brought them into the halls of power across the UK and beyond – Stormont, Westminster, Brussels and even in the US Congress, as part of a delegation that gave testimony to the Helsinki Committee in 2011.

The hard graft over the past decade or so paid off, as campaigners were able to bring dossiers of the evidence they had gathered as well as their own personal stories of loss.

John said: “For the non-believers, we had the police reports, the autopsy reports. If I said my father was shot 14 times, I could produce the autopsy report that said so. People were listening and you were converting people who wouldn’t necessarily have been receptive.”

One notable meeting came with the then Northern Ireland First Minister, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Peter Robinson. He was a lifelong unionist, who often defended the actions of security forces – the police and the Army – from criticism by pointing to the brutality of paramilitaries such as the IRA at the time. As such, he was not a natural ally for the campaign.

It was reported at the time that Mr Robinson was shocked to hear allegations that there had been no proper police investigation into the deaths.

Janet Donnelly recalled Mr Robinson saying he “couldn’t believe” that was the case, but she was able to produce the police report into her father’s death – a single page with very little text. “My view was if you can’t back it up, don’t say it,” she said.

Campaigners continued to crank up the pressure on the authorities to provide a full public inquiry. However, after the cost of the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday spiralled to £195m, the Northern Ireland Office (NIO), which represents the UK government in Northern Ireland, ruled out a similar inquiry for Ballymurphy.

The campaign went in a different direction. In 2010, the Ballymurphy families delivered a “couple of box folders of paperwork” to Northern Ireland’s then Attorney General John Larkin.

Documents were submitted to the attorney general.

Documents were submitted to the attorney general.

Within a year, he would order new inquests into the deaths of 10 people killed at Ballymurphy. It was a huge step forward for the campaign, even if for some, such as Carmel Quinn, it was short of the full investigation they wanted.

She said: “They haven’t given us anything out of the ordinary and it doesn’t cost them any money – an inquest is basic human rights. That’s all my brother has received.”

The Inquests

The new inquests were ordered in 2011, but it would take seven years of preliminary hearings before they officially began in November 2018.

The hearings were expected to last for four months, but ended up running for 16 months, until March 2020. Weeks later, the Covid-19 pandemic struck, ensuring that the families’ wait for a final report would stretch until May 2021 – almost 50 years since the Ballymurphy shootings took place.

Whereas the six inquests in 1972 each lasted a single day, and heard no evidence from soldiers in person, this one would hear almost 100 days of evidence from more than 150 witnesses, including 60 former soldiers, more than 30 civilians and experts in ballistics, pathology and civil engineering.

Among the witnesses to appear in person were a number of former soldiers, including General Sir Mike Jackson, who worked as a press liaison in Ballymurphy in 1971.

There were plenty of significant decisions for the coroner, Mrs Justice Keegan, to make before the inquest opened, such as in 2015 when she ruled that the body of Joseph Murphy, the father of Janet Donnelly, could be exhumed.

The coroner and her staff had other hurdles to overcome. Important documents dating back decades had been lost, including one which held the names of soldiers who gave statements to the original inquests under anonymity. Without it, it was impossible to know who gave many of the original statements in 1972.

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) was admonished by the coroner two months before the inquest officially began. It had already been accused of attempting to hold up proceedings at “the 11th hour” by a Ballymurphy family solicitor, when it handed over a database with the names of 5,000 former soldiers.

In September 2018, Mrs Justice Keegan told the MoD there was an obligation to provide documents and that they should be in an “intelligible format”.

When the inquest did open, it was a bittersweet moment for the families. They had finally achieved their day in court, but the testimony forced them to relive their darkest days.

“None of the families were prepared for how emotional it would be,” said John Teggart. "Raw was the right word. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. That was the only thing that shocked me, we were hardened campaigners as I thought until those days – it was an emotional rollercoaster."

But their shared trauma, and fight, strongly bound them together. In recent years, they organised an annual candlelit vigil to remember their loved ones and remind the world of their continued search for justice. They had kept the flames burning in the dark all these years, together.

“The support we had for each other was absolutely fantastic. We were one big family consoling each other," John said.

The most emotional moment for Janet Donnelly came when she heard a statement from the son of a soldier who was at Ballymurphy when her father was shot.

“My father had told my mother that there was a young soldier that tried to help him, he asked for medical attention and a padre. My mother always told us that story. And then the son of a soldier gave a statement saying his father helped one the victims, that he had asked for medical treatment and a padre…and that was just, like, the moment. I was just thinking, ‘thank you, these are my daddy’s words coming through’.

There were others who did not co-operate. Despite the organisation’s known presence in the area, no IRA members gave evidence. Likewise, a so-called “interlocutor” for the loyalist paramilitary group the UVF known as Witness X, did not show up to testify on three separate occasions.

As the inquest proceeded, more soldiers began to give evidence, often anonymously and behind a screen. Their participation was the subject of some controversy, particularly to veterans’ groups who saw it as another example of soldiers – now older, sometimes in ill-health – being the subject of continuous investigation arising from decades-old Troubles legacy cases.

One former soldier, Henry Gow, bluntly told the inquest it was a “witch hunt”.

To some, like John Teggart, it felt that many soldiers “just didn’t answer questions” when they took the stand.

In the end, only one former soldier who testified admitted shooting anyone, the man known as M3 who said it was possible that a shot he fired inadvertently hit and killed Edward Doherty.

One military witness, who wanted to be completely shielded from the court, turned up in what Carmel Quinn described as a “cartoon wig”.

“How disrespectful is it to come to court like that, with families who had lost loved ones in front of you?” she said.

There were some high-profile exceptions – Gen Sir Geoffrey Howlett, a former commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, denied his men lost control, but did say that “most if not all” of those shot in Ballymurphy were not in the IRA.

Another former soldier, who was not serving but was in the Ballymurphy area on leave at the time, testified that he saw civilians being shot by paratroopers.

But General Sir Mike Jackson was the eyewitness many onlookers wanted to hear the most.

His 45-year armed forces career had brought him from Sandhurst to the very top, as the Army’s chief of general staff. As one of the highest-profile military figures in the UK, his appearance in Court 12 of Laganside Courthouse on 12 May 2019 for a sitting of the Ballymurphy Inquest generated even more anticipation than usual.

David Cameron announcing the findings of the Bloody Sunday report in 2010

David Cameron announcing the findings of the Bloody Sunday report in 2010

He was no stranger to a witness box, having given evidence to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry some years earlier. He was a captain with the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment on the day when paratroopers were found to have killed 13 innocent civilians. Their deaths were famously described as “unjustified and unjustifiable” by then Prime Minister David Cameron.

Part of Gen Jackson’s role in Ballymurphy was to give press briefings. It was put to him by Sean Doran, counsel for the coroner, that it was likely he was the unnamed Army captain quoted in the Belfast Telegraph newspaper labelling some victims as "gunmen".

“I wouldn’t disagree,” Gen Jackson replied, adding that he had no “specific recollection” of any such interview. He said in retrospect he should have described the gunman as “alleged” and admitted he hadn’t seen any shooting or the bodies of those killed or injured, but that the information was based on what he was told by a company commander.

He told the court: “Let me say to the families, who so long ago lost their loved ones, for me it’s a tragedy. It's a tragedy which is hugely regrettable, but I would also say that anybody who loses their life as a result of violent conflict is also a tragedy. I too have lost friends, so be it.”

Carmel Quinn was there to hear Gen Jackson speak about the death of her brother.

“He said sorry to the families but – and I was waiting on the but – he had ‘lost people’ too. What does that mean? Does that justify murdering my brother because somebody else killed one of his soldiers?

“That wasn’t an apology at all and, out of them all, he was a man that I’d have liked to see prosecuted – but it’s never going to happen.”

Mary Kate Quinn, Carmel Quinn, Rita Bonner and Geraldine McAllister arrive at the publicaiton of the inquest's findings

Mary Kate Quinn, Carmel Quinn, Rita Bonner and Geraldine McAllister arrive at the publicaiton of the inquest's findings

Carmel said she would prefer not to see “a 77-year-old man in the dock” over the death of her brother, but rather that the “British state held their hands up and said, ‘yes, we did this’.”

“They’re crying out about their veterans being brought up in front of courts – well, then take responsibility. Don’t be passing it on to the ordinary soldiers that were on the ground. Pass it on to the people who were giving the commands.”

It would be another 10 months after Gen Jackson’s appearance before oral hearings came to an end. It had proved to be an exhausting process.

John Teggart said: “I work in construction and a day at the inquest is worse and more draining than a day’s work on a building site. A lot of people have had their emotions raised, to where they’ve never before. So we’re coming down from that. But I think we’ll get the right result in the end and we’ll do what we have to do after.”

The Ballymurphy Massacre campaign banner goes with the families wherever they go.

They took it with them to Westminster and Brussels, Washington and Dublin, wherever they went to win support or lobby for action – it was there.

Not even Covid-19 could stop the banner from being carried into the temporary courtroom set up in Belfast’s International Conference Centre at the city’s Waterfront Hall, where Mrs Justice Keegan delivered her long-awaited verdict on Tuesday.

She spoke for over two hours and 30 minutes, going through each shooting incident and her findings at length. Later, all 715 pages were published online.

Each time the coroner wrapped up her conclusions on an incident, a determined round of applause rang around the room. The loudest one came at the very end, when she declared “that all the deceased in this series of inquests were entirely innocent of any wrongdoing”.

“I do express the hope that some peace has been achieved now that the findings have been delivered.”

When speaking before the verdict, Carmel Quinn, Janet Donnelly and John Teggart were hopeful of a verdict like this – exoneration of their loved ones, confirmation of what they knew all along. But there was understandable reluctance to hope too hard.

Now, in the words of Patsy Mullan to a press conference later on Tuesday, the truth had finally been told.

Briege Voyle said she “never thought I would see the day... they actually had the courage to tell the truth”. Carmel Quinn said her family “would never give up fighting” for her brother John and called for further accountability.

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) said it recognised “how difficult the process had been for all those affected by the events of August 1971 and the inquest” and said it would “review the report and carefully consider the conclusions drawn”.

Lord Dannatt, a former head of the Army, said the deaths and the long wait for the truth was a “double tragedy”.

“Frankly, these matters should have been investigated much more thoroughly a long time ago.”

That these 10 deaths were investigated now, years later, is largely down to the determination of the victims’ loved ones. Pat Quinn, the brother of Frank, told the media that it was “hard to believe that our families have had to do it ourselves”.

While the Ballymurphy families were finally hearing the truth, one avenue for them and many other families still grieving loved ones lost in the Troubles may soon be blocked. The UK government has committed to legislation next year that will, according to leaked details, ban all Troubles-era prosecutions under a statute of limitations.

The move would essentially result in an amnesty for all Troubles-related deaths and mean victims – including the Ballymurphy families – will be unable to pursue criminal prosecutions.

In Northern Ireland, where dozens of legacy inquests are due to be heard and almost 1,000 unsolved Troubles cases are still being looked at by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), the move has generated an intense backlash in some quarters.

John Teggart speaking at a news conference

John Teggart speaking at a news conference

Addressing the media after the inquest, John Teggart could not hide his anger: “The British government now wants to deny us the chance for justice by introducing an amnesty for these murders.

“I want to speak directly to the people of Britain at this moment. Can you imagine what would happen if soldiers murdered 10 unarmed civilians on the streets of London, Liverpool or Birmingham? What would you expect – an investigation? Would you expect justice?”

He added: “The truth is more powerful than any government. We hope to give strength to all the other families who, like ourselves, are seeking truth and justice. It can be done, don’t give up.”

You can find the full findings from Coroner Mrs Justice Keegan here

Credits:

Photography: Charles McQuillan

Additional Images: Getty Images, Pacemaker Press, Press Association, Reuters

Archive Maps: Land and Property Services / Ordinance Survey

3D Graphics: Andrew Davidson

Additional Material: Frank Martin

Online Production: Peter Hamill

Assistant Editor: Darwin Templeton

Editor: Pauline McKenna