House-buyer time machine

‘We can't afford to buy a house now. But what could we have got in the past?’

Charlie Chatwood and Tacita French met on dating app Tinder two years ago and now want to buy a house.

Together they earn £43,500 - just above the average (median) for a couple in their mid-20s. They could get a joint mortgage of about £160,000 - between three and four times their gross income. But even with a hefty deposit, they would struggle to buy anything.

They live in West Sussex where - according to property websites - average homes sell for about £375,000. And while they would love to live in nearby Brighton, they know that’s just not possible in 2019. But could they have bought there in years gone by?

With an economist, historian and personal finance expert guiding them, Charlie and Tacita travelled back in time to five Friday paydays from the past.

How far would our couple’s money have stretched?

Friday 18 October 1968

‘The year of peak housebuilding’

The bay windows, high ceilings and feature fireplaces of period properties - so cherished by house-hunters today - were not what first-time buyers wanted in 1968.

Flat-fronted, angular, box-like homes were all the rage.

“There was still a post-war feeling that old stuff was still a bit bad – and that modernity, and modern houses, would make things better,” says historian Prof Claire Langhamer from the University of Sussex.

She is helping paint a picture of what life was like for couples in their mid-to-late 20s in all the years visited by Charlie and Tacita.

It was an aspirational time - but those aspirations could not always be fulfilled.

“There were women's and DIY magazines showcasing these beautiful shiny new homes with really bright vibrant colours and modern furniture – but that wasn’t really what a lot of people were experiencing day-to-day.”

In 1968, about one-eighth of all homes still lacked basic amenities - like baths, hot water and indoor toilets.

It was the end of a decade when housebuilding had mattered - with city slums cleared for new tower blocks and the creation of fresh waves of post-war new towns.

1968 remains the peak post-war year for housebuilding, with more than 425,000 new-builds completed across the UK.

In Brighton that night, three big stories were on the front page of the local paper – the Evening Argus. Jacqueline Kennedy, widow of US president John F Kennedy, was about to remarry. Beatle John Lennon - with his “Japanese artist friend” Yoko Ono - had been arrested in London for possessing cannabis. And runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos had been suspended from the US Olympic team after their “Black Power” demonstration.

Inside the paper, there were dozens of homes for sale - and the idea that “new was good” was very evident.

A two bedroom flat in a new 10-storey block of flats on Worthing seafront was priced at £5,150.

The same money would have bought a new three bedroom semi about 10 miles from Brighton - on Wimpey Homes’ Roman Way Estate in Burgess Hill. The newspaper advert lists the benefits of buying brand-new. New homes featured an immersion heater, veneered internal doors and plastic rainwater pipes and gutters.

£5,150 in today’s money is just over £65,000.

The price tag may sound cheap, but wages were much lower compared with today’s earnings.

“In many ways 1968 seems even further away from us now than it really is,” says economist Jonathan Cribb from the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

People were generally poorer than they are today, he says, and the role of women in society was also very different - with many not having the means to be financially independent. Statistics from the IFS reveal that of the 84% of twenty-somethings in a couple, 83% would have been married.

“The average age of marriage for women was about 22 - but working-class women got married even earlier,” says Claire Langhamer.

Marriage was the life event that validated relationships and made home-owning possible. That was especially true for women, who often couldn’t get a mortgage or credit without a male guarantor.

And the general limited availability of credit - for men and women - meant that people had to plan ahead for big purchases. “People saved for their ‘bottom drawer’ ready for when they got married,” says Claire.

But most parents of the 1968 first-time buyers would not have been in a position to help much financially. They would have been born in the 1920s and 30s. “We’re not talking about a very rich generation,” says Jonathan.

In 1968, nearly all men in their mid-20s would have been in work - about 97%.

Roughly 60% of couples that age had children and 45% of women had jobs - though many of the positions on offer did not pay well.

Tacita is not impressed by some of the job ads in the Argus.

- We need women of all ages for simple assembly work – minimum wage £10-16s-8d

- Vacancies for girls - of a general clerical nature - applications are invited from women aged between 18 and 25

“Women were still really corralled into low-pay, low-status jobs,” says Claire Langhamer. “But employers did want to get them into the workplace.”

Millions of Britons – somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters – did not have a bank current account in 1968.

To get a mortgage, a couple like Tacita and Charlie would have probably opened a savings account at a local building society – to build up a deposit – and then applied for a home loan at that branch.

“And even then, some people would have to wait for months,” says personal finance expert Prof Sharon Collard from the University of Bristol. “Building societies generally only lent money they actually had. Financial services hadn’t yet opened up to the international money markets.”

In 1968, our couple would have a combined gross income of £1,500 a year.

The sums for October 1968:

· Tacita and Charlie have a 2019 gross income of £43,500, which is slightly above average for couples in their mid-20s

· In 1968, a couple in a similar position would have an estimated gross income of £1,500 – that’s £19,000 in today’s money

· After saving a rough 20% deposit, they could borrow about £2,750 at an interest rate of 7.6%

· In 1968, they could buy a property costing about £3,400 – that’s just over £43,000 in today’s money

Sources/calculations: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Savills UK, Building Societies Association, Bank of England

Tacita and Charlie look through the Evening Argus. What would £3,400 get them?

There is a fair selection of affordable properties in Brighton and Hove - flats and small houses. But most are older style properties - not so fashionable at the time - and they may not have had mod cons.

“Well that's a hell of a lot of house for not very much money,” says Charlie of the terraced house close to the station. “Potentially your forever home.”

The couple are curious why homes in 1968 seem more affordable, when their 1968 earnings would have been - comparatively - less than half of what they take home today. “So why can’t we buy a house now?” asks Charlie.

“Fundamentally it's because your real income has doubled - plus a bit more - since 1968. But house prices have gone up about fivefold,” says Jonathan Cribb.

“And in that sense, 1968 would seem easier for a couple like you than it does today. But I don't think we should underestimate all of those difficulties of a much poorer society – they make day-to-day life much harder.”

LISTEN: Charlie and Tacita travel back to 1968 - when Mary Hopkin, Marvin Gaye and Tom Jones were in the charts

And then jump forward with them to the late 1970s…

Friday 23 November 1979

‘When first-time buyer mortgage rates hit 15%’

Getting on the housing ladder would have been more of a challenge for our couple at the end of the 1970s.

Yes, progress towards equality meant Tacita would be much more likely to be earning a wage than 11 years before, but the mid-to-late 70s had been a white-knuckle economic rollercoaster.

And to top it off, the cost of borrowing had just become the most expensive it had ever been.

That Friday was when mortgage rates rose from 11.75% to 15% for first-time buyers - as a result of the Bank of England raising its base rate to 17%. Existing borrowers would - according to the Building Societies Association - have to pay 15% from January 1980.

The cost of everything seemed to be going up fast.

UK inflation was running at about 13%-14% - explains economist Jonathan Cribb - down from a high of 25% in 1975. In 2019, the rate is about 2%.

“You would go to the shops every couple of weeks and visibly see those prices going up. But you’d still have the same one-pound note in your pocket,” he says. Charlie – born in 1992 – raises an eyebrow.

“I can see that people's quality of life was certainly decreasing rapidly - and if wages weren't rising too, that would have caused discontent.”

Between 1968 and 1979, the cost of some basic food items rose considerably.

In pre-decimal 1968 - when prices were displayed in pounds, shillings and pence - a pint of milk cost 10 old pence, or 10d. That works out at just over 4p when converted into the decimal system.

By 1979 it cost nearly 15p - a price increase of about 275%.

If Charlie and Tacita had decided to have a cheap night in front of the TV that Friday, they would have had a choice of only three channels.

Southern Television, the local ITV company, had the quiz 3-2-1. On BBC Two, there was a new series of Better Badminton. While on BBC One, viewers could enjoy an episode of the sitcom Are You Being Served?

The irony is that from midnight that evening, television viewing would also become more expensive.

“£9 is slapped on the cost of colour viewing - TV Licence Bombshell,” read the main headline on the Evening Argus newspaper. The cost of a colour licence was rising from £25 to £34, and a black and white one from £10 to £12.

With prices for basic items rising fast, sales staff needed to work harder to get people to spend money on big ticket items. Among the car adverts for Morris Marinas, Triumph Dolomites and Ford Cortinas, one garage was offering coupons for 50 gallons of petrol with every used vehicle sold.

“People would’ve been spending a lot of money on basic goods, so that explains why salesmen are offering coupons - some kind of incentive,” says personal finance expert Sharon Collard.

In 1979, a gallon of four-star leaded petrol cost 98p - that’s about 22p a litre (86p in today’s money).

But the 1970s witnessed not only economic turbulence, but also moves towards equality.

“It was perhaps the most equal of the decades we’re looking at, with the differential between the richest and the poorest in society at its smallest,” explains Claire Langhamer. “There were discussions around women’s equality and gay rights. There was a tangible sense of change in the way people wanted to be.”

Trade union strikes may have made the news almost daily, but our experts agree that 1979 offered more job security for a greater number of people than today.

“There were still large numbers of people in relatively stable public sector employment. National industries offered a sense of a collective welfare,” says Sharon Collard.

Council houses made up just under a third of all UK homes in 1979 – some 6.5 million properties.

“The fact that it was just about the peak year for rentals from local authorities really mattered,” says Claire Langhamer. “If you were young and in need of a home, that would make the whole situation feel a little less precarious than it does now.”

As a couple in their mid-to-late 20s, the likelihood is that Charlie and Tacita would be married with a child in 1979 - similar to 1968.

But significantly, Tacita would be much more likely to be working than in the late 1960s. By 1979, 60% of young adult women were in work, compared with only 45% in 1968. A 15 percentage point increase in just over a decade.

The Sex Discrimination Act of 1975 should also have let Tacita get a mortgage in her own name, without the need for a male guarantor. And a relaxation of the marriage law in England and Wales, at the start of the 1970s, made it easier for couples to split.

“This shift to treat marriages more like relationships - rather than an institution at the heart of society - was really crucial,” says Claire Langhamer. “The housing situation changed. When a relationship ended, you might have needed two houses rather than one.”

So how much did homes cost in 1979?

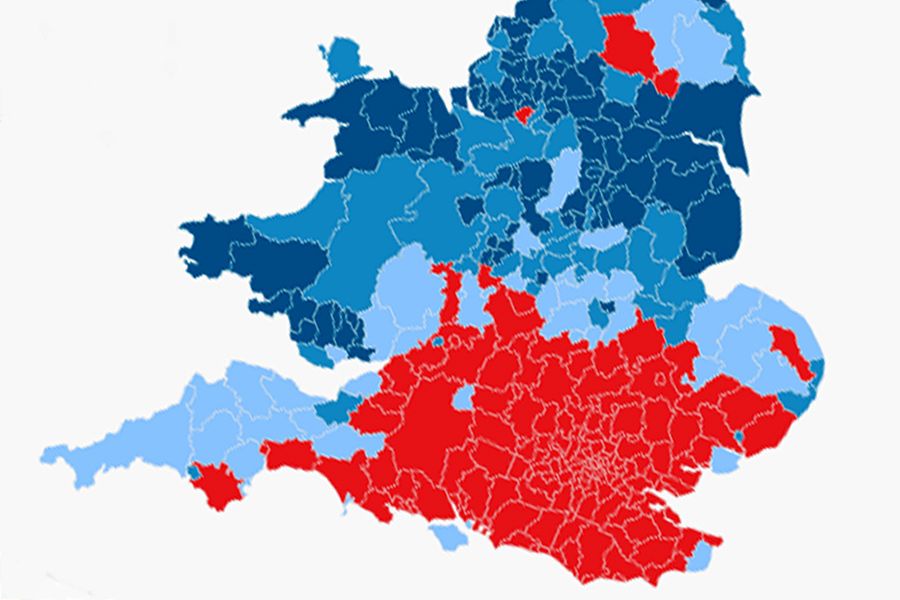

The average house price in England was approaching £17,000 – and the North-South divide was not so extreme as today.

In London an average property cost £22,000. In Yorkshire, the figure was £13,000.

And about £13,000 was the amount Charlie and Tacita could have afforded in Brighton - with their income of £6,000.

The sums for November 1979:

· Tacita and Charlie have a 2019 gross income of £43,500, which is slightly above average for couples in their mid-20s

· In 1979, a couple in a similar position would have an estimated gross income of £6,000 – that’s about £23,300 in today’s money

· After saving for an average 15% deposit, they could borrow about £11,000 at an interest rate of 15%

· In 1979, they could buy a property costing about £12,900 – that’s about £50,200 in today’s money

Sources/calculations: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Savills UK, Building Societies Association, Bank of England

“You’d be paying a mortgage interest rate of 15%. Those monthly payments would be quite steep, more than 35% of your take-home pay,” says economist Jonathan Cribb.

“However, the accompanying high inflation would have helped reduce the value of what you owed quite quickly, and your wages - in cash terms at least - would have risen steadily. So the real value of your mortgage debt would be gradually reducing.”

Charlie and Tacita look through the Evening Argus. What could they have bought?

The affordable homes are smaller than those in 1968.

“It doesn't look as good as 1968 but there are some pretty reasonable flats – and still more doable than now,” says Charlie.

“Not only is it more affordable in relation to what our income would have been, but it sounds as though we could have expected better long-term job security. Today, there is no golden ticket.”

LISTEN: Charlie and Tacita travel back to 1979 - when Abba, Queen and The Jam were in the charts

And then jump forward with them to the late 1980s…

Friday 20 May 1988

‘The year when house prices rose by 25.6%’

By the late 1980s, our couple would be wealthier - with enough money to pay for big hairstyles and fashionable clothes.

But with house prices rising fast in southern England, would they have been priced out of the market?

Many of today’s social inequalities, in terms of geography and income, really became much more stark in the 1980s - says economist Jonathan Cribb.

“It was the decade when - relatively - the rich did better than the middle, the middle did better than the poor, and the South did better than the North.”

That Friday, Labour leader Neil Kinnock attacked Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist, free-market policies – accusing her of creating a “speculators’ paradise”. He used the catchphrase of Harry Enfield’s comic character - Loadsamoney.

“The money’s only here for the money… not loadsaproduction, not loadsajobs - just loadsamoney,” he told the Welsh Labour Party. “We’ve got the loadsamoney economy. And behind that comes loadsatrouble.”

On the news that night, Margaret Thatcher responded robustly. “Our policies have created the wealth which we have then been able to distribute… everyone has benefitted.”

In May 1988, parts of the UK - the traditional industrial areas away from London - were still experiencing the after-effects of the early 1980s recession. When they came to power in 1979, the Conservatives had grappled with high inflation, high interest rates and a strong pound. Unemployment rose sharply.

But a couple like Charlie and Tacita, living in a relatively prosperous part of the country, would probably have both been in work. Their personal finances would have risen by about 40% since 1979 - even after inflation - says Jonathan Cribb.

And their increased wealth would have boosted their purchasing power.

That Friday, our couple may well have gone to the cinema to see Three Men and a Baby, The Last Emperor or Wall Street.

“Partly, that leisure spending was being supported by massive growth in consumer credit – people using credit cards,” says personal finance expert Sharon Collard. She explains how the financial industry could “breathe” more by the end of the decade.

“Until 1980, there was the so-called ‘bank corset’ which kept lending within specific Bank of England limits. It was removed by the Chancellor Geoffrey Howe. The government wanted to open up the market to international flows of money.

“It was a time when banking became sexy. Big bonuses, long lunches, wine bars – a nice lifestyle.”

The 80s also offered ordinary people the chance to invest.

“You know these British Gas shares? They’re really easy to do,” went the 1986 TV ad. “If you see Sid, tell him!”

No-one ever saw Sid, but the British Gas privatisation campaign worked.

“Individuals were being positioned - almost whether they wanted to be or not - as financial experts over their own lives,” says historian Claire Langhamer.

“It was the idea everybody should’ve been thinking how to make lucky investments. And it really was luck. It's all historical accident - where you end up - when you can buy a house - if you have cash to buy shares.”

By 1988, fewer people of Charlie and Tacita’s age cohabited. About 60% of twenty-somethings lived with a partner, down from 80% in 1979.

So how did the 1988 housing market stack up?

Average house prices between 1979 and 1988 had risen by 200%. Even accounting for inflation they were up 75%, says Jonathan Cribb.

And 1988 remains the year - according to Office for National Statistics figures dating from 1980 - that saw the greatest annual UK house price inflation. Prices rose by 25.6%.

But the North-South divide was widening.

At the time, the Building Societies Association cited three reasons as to why it was happening. Firstly, lower unemployment rates in the South meant there was greater purchasing power. Secondly, City bonuses were being used to buy property in London. And thirdly, the completion of the M25 motorway had improved transport links in the South East.

It was also easier to get a mortgage. With more banks in the market, more products were available. And deposits, proportionally, were getting smaller.

“We saw high loan to value. Lower deposits and sometimes no deposit whatsoever,” says Sharon Collard. “It was a crazy time.”

The Conservatives’ Right to Buy policy also limited the availability of social housing – putting more pressure on the private sector. Council tenants could buy their properties at a discount – with restrictions placed on the number of new homes local authorities could build.

The policy “did give a lot of housing wealth to people who had none before”, says Jonathan Cribb. People began to see houses as investments rather than just homes, says Claire Langhamer.

In 1988, Charlie and Tacita’s joint income would have been £15,000.

The sums for May 1988:

· Tacita and Charlie have a 2019 gross income of £43,500, which is slightly above average for couples in their mid-20s

· In 1988, a couple in a similar position would have an estimated gross income of about £15,000 – that’s just over £33,000 in today’s money

· After saving for an average 5% deposit, they could borrow a little over £33,000 at an interest rate of about 9.8%

· In 1988, they could buy a property costing roughly £35,000 – that’s about £77,500 in today’s money

Sources/calculations: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Savills UK, Building Societies Association, Bank of England

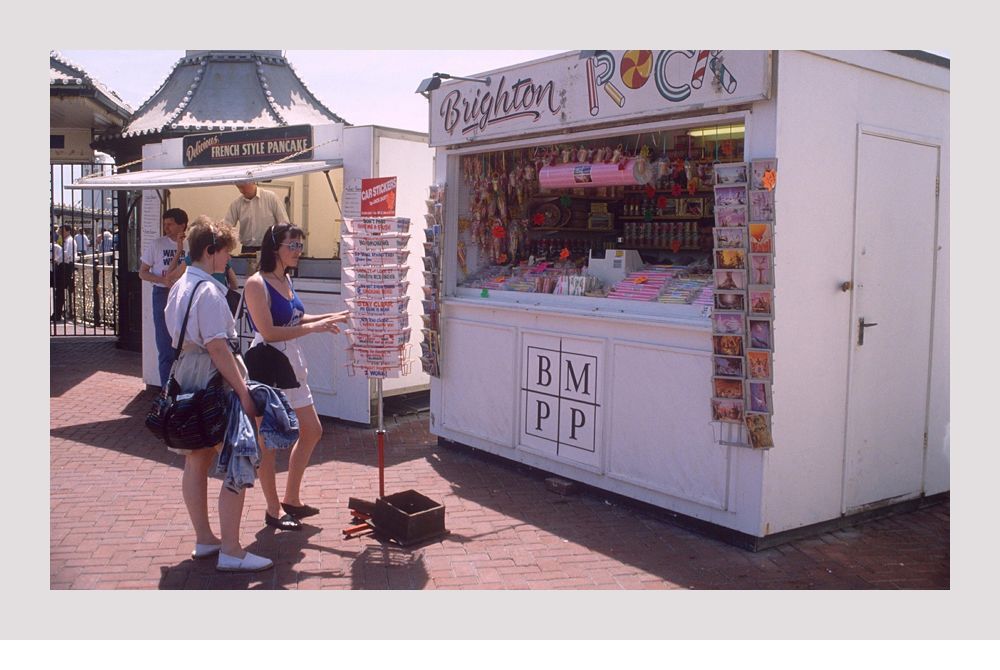

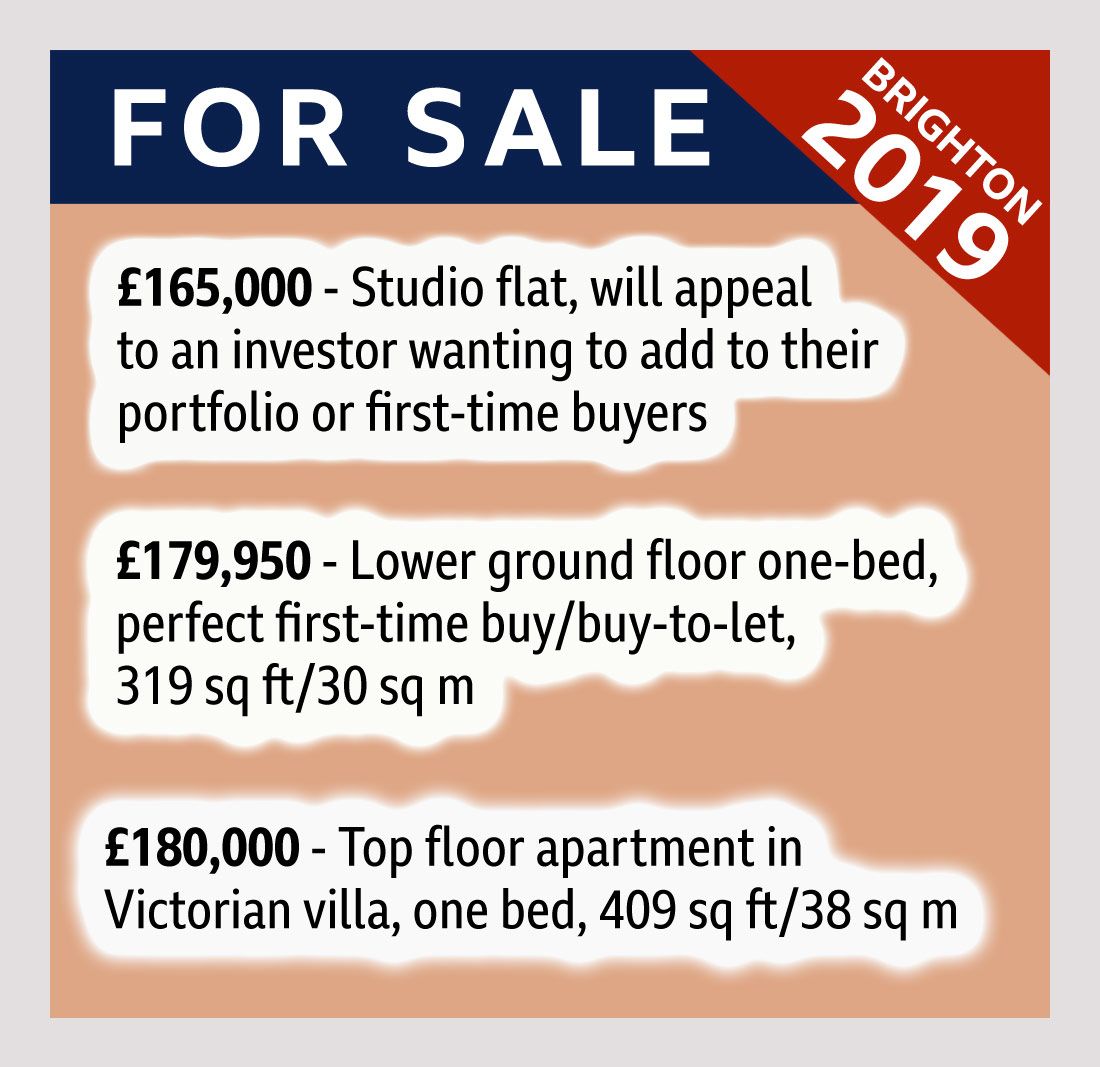

But Charlie and Tacita’s £35,000 budget would not have stretched very far in Brighton.

In property pages, there is nothing that cheap - although a few studio flats come close.

“We're looking at the real lower end,” says Tacita, “which is interesting because in 1979, with £13,000, that would have bought us a flat. And in 1968 we’d have got a house. It's changed quite a lot.”

“But the ratio of income to house price is still such that we may have been able to save and get something better,” says Charlie.

“I'm guessing what people did was compromise and buy a bedsit,” says Sharon Collard. “But they’d think, ‘Because of house price inflation it's only going to be a few years before we can trade up.’”

LISTEN: Charlie and Tacita travel back to 1988 - when Belinda Carlisle, S-Express and New Order were in the charts

And then jump forward with them to the late 1990s…

Friday 2 May 1997

‘A sweet spot?’

The political landscape of the UK had been radically redrawn overnight. The Conservatives were out and Tony Blair’s New Labour were in.

As John Major left Downing Street that morning, he told news crews that Britain was “in far better shape” than when he had become prime minister in 1990.

The economy did seem to be in a good place.

“Inflation was about 2%, employment was rising fast, unemployment was falling - you had a kind of sweet spot,” says economist Jonathan Cribb.

Average house prices in England were just over £60,000 - about 20% lower than the late 1980s, adjusting for price inflation.

Could 1997 be a good year for our first-time buyers Charlie and Tacita?

It certainly looks more promising than a few years earlier, when the 1980s housing bubble burst, interest rates soared again and the country headed into recession.

Many first-time buyers who had bought in the boom found themselves in negative equity - and owed more to the bank or building society than their home was actually worth.

“Negative equity was a national shock to the system,” says personal finance expert Sharon Collard. “We have a persistent view that bricks and mortar are the safe investment - but in 1992 alone, 75,000 families had their homes repossessed.”

In general though, says Jonathan Cribb, the early 1990s slump was not as hard-hitting as the early 1980s recession. “Economically, it's not something that took years to recover from.”

But for a few who had lost their jobs and got redundancy payouts - investing in property looked an attractive option. Specific buy-to-let mortgages were launched.

“It was the idea that housing wealth created more wealth,” says Sharon Collard. “If you could afford a house, you could afford a second house. And you could rent out that second house to pay towards your retirement.”

Despite the house price falls and negative equity at the start of the 1990s, average deposits in 1997 for first-time buyers were only about 5% - and there was still the option of 100% mortgages.

By the late 1990s - 75% of women in their mid-to-late 20s would be working, about a third would have a child and about 60% would be living with a partner. That’s not too far off today’s figures says Jonathan Cribb.

Our couple’s wages would have grown since 1988, but at a slower rate than the 80s boom years. Between them in 1997, they would earn about £24,000.

The sums for May 1997:

· Tacita and Charlie have a 2019 gross income of £43,500, which is slightly above average for couples in their mid-20s

· In 1997, a couple in a similar position would have a gross income of £24,000 - that’s just over £37,000 in today’s money

· After saving for an estimated 5% deposit, they could borrow about £57,000 at an interest rate of about 6.5%

· In 1997, they could buy a property costing nearly £60,000 - that’s nearly £93,000 in today’s money

Sources/calculations: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Savills UK, Building Societies Association, Bank of England

“Your 1997 budget of nearly £60,000 is roughly back at the national average house price – just like in 1968,” explains Jonathan.

Looking through that night’s “election special” edition of the Evening Argus, Charlie and Tacita are pleasantly surprised. There’s an abundance of choice.

They could have had their pick of flats across Brighton and Hove - and even stretch to a house.

“We’re looking really good in 1997,” says Charlie. “Of all the decades so far, would this have been the best one for us to have bought a house?”

“You're going to get me as close to saying ‘Yes’ for an economist, as you're going to get me to say,” jokes Jonathan.

In 1997, the average house price was roughly two-and-a-half times the average income for people in their mid-to-late 20s - similar to 1968.

“But you would have been so much richer in 1997 than you would have been in the late 1960s,” says Jonathan. “And the standard of homes was better - you’d be more likely to have central heating or double glazing.”

For women, says historian Claire Langhamer, there is a clear winner.

“There’d been that shift in women's financial autonomy, earning capacity and lack of reliance on marriage. In the unhappy event of you two splitting up in 1997, then you, Tacita, would have been able to buy a home on your own.”

LISTEN: Charlie and Tacita travel back to 1997 - when D:Ream, Blur and the Spice Girls were in the charts

And then jump forward with them to the late noughties…

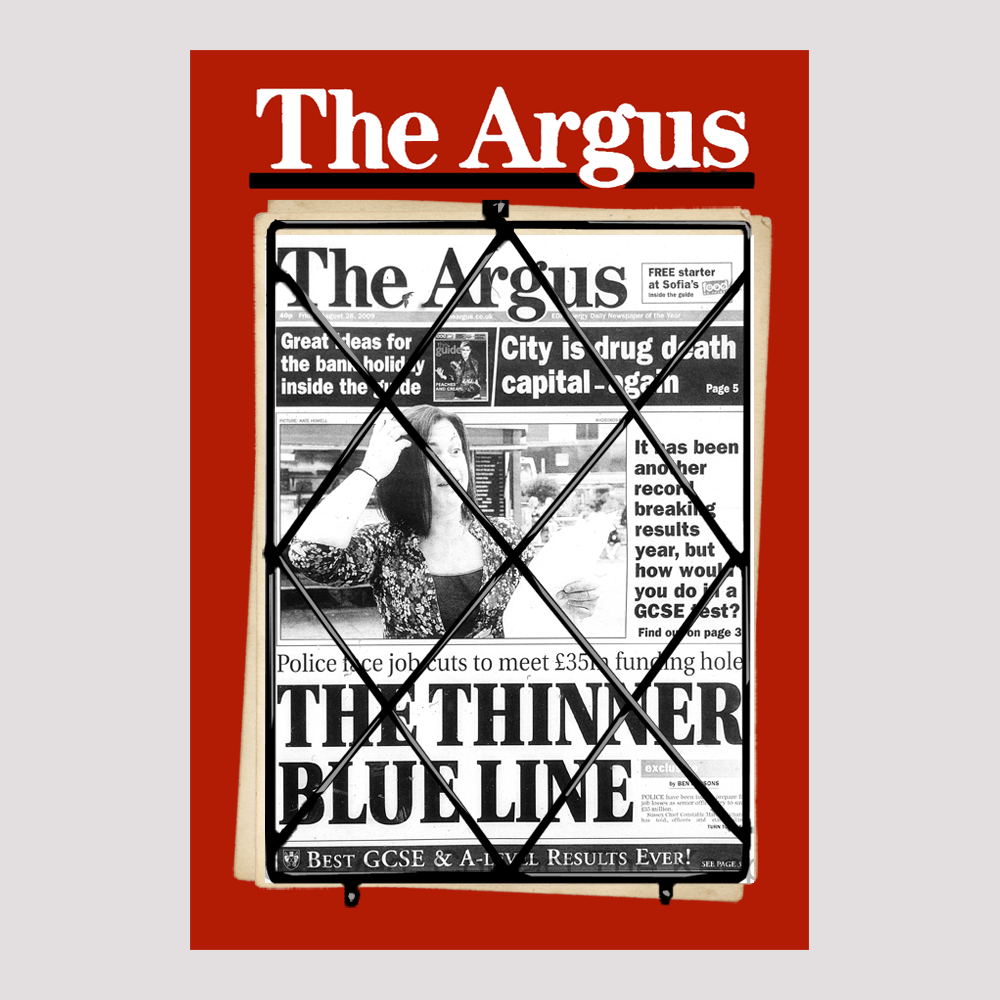

Friday 28 August 2009

‘After the Great Recession’

The UK economy had been going backwards - shrinking - for over a year.

The deepest recession since World War Two was just about over, although its effects were still being felt.

“We really had a true global financial crisis,” explains economist Jonathan Cribb to our couple Tacita and Charlie - who were aged 14 and 16 at the time.

“We hit the credit crunch in slow motion. In the UK, the bank Northern Rock got into trouble in late 2007, and then all hell broke loose in the autumn of 2008 with Lehman Brothers going bust.”

Companies laid off staff, froze pay or shortened working hours to try to survive. The flow of money around the economy slowed - access to credit was restricted. And that fed through into the housing market.

House prices, which had risen steadily since the mid-1990s, had been falling in the recession. But this time, unlike in 1997, there was no sweet spot.

“For prospective house-buyers like yourselves, 2009 was a funny place,” says Jonathan.

In August 2009, the average house price in the south-east of England was just above £206,000.

“House prices in real terms had grown by 120% since our last year - 1997. But incomes were up by only 25%. That made it a lot harder to buy a house,” he says.

The Great Recession - as it is now known - also had a greater impact on young people than older generations. Twenty-somethings suffered the biggest falls in earnings and higher unemployment rates. Companies tightened their belts and stopped hiring.

The late 1990s and first half of the 2000s had seen house prices soar, particularly in the most crowded part of the UK - London and the South East. Demand was outstripping supply. Buy-to-let and overseas investors continued to look for property alongside traditional house-hunters.

“And we start to see television shows like Homes Under the Hammer - about selling your house to make a profit,” says historian Claire Langhamer.

Fewer homes were also being built. Housebuilding figures fluctuated around the 200,000-a-year mark at the start of the noughties - less than half the total in 1968. By 2009, the number of completed dwellings in the UK had dropped to 157,000.

And during the 2009 credit crunch, for those young buyers living in expensive parts of the country, getting a mortgage would also have been tricky.

“There was a massive contraction of mortgage lending,” says personal finance expert Sharon Collard. “Loan to value of 75% became fairly standard. You’d need a 25% deposit - a big chunk of money. Lenders’ appetites for risk had completely collapsed - and the regulators forced them to become more responsible for their lending.”

The tough conditions are borne out in figures on home ownership from the Resolution Foundation think tank. In the south-east of England between 1988 and 2009, home ownership among 25 to 34-year-olds fell from 58% to 36%. By 2018 it had dropped further – to under 30%.

But for those young people able to get on the 2009 housing ladder, there was one “saving grace” says Jonathan Cribb. Record low interest rates.

“This was the point where the gap between renters and owner-occupiers opened up. Rents had increased over the decade, and when the Bank of England cut interest rates to keep the economy afloat, that brought mortgage rates down.

“Those who did get a home benefitted from very cheap credit.”

Charlie and Tacita wonder about their August 2009 earnings.

Looking at his spreadsheet, Jonathan says a young couple like them - earning slightly above average wages - would have earned about £37,000. In today’s money, that’s almost £46,000 - and more than they currently earn.

“It means over the past 10 years young people's earnings have actually fallen back a bit - one of the reasons why it’s so hard to buy in 2019,” says Jonathan.

The sums for August 2009:

· Tacita and Charlie have a 2019 gross income of £43,500, which is slightly above average for couples in their mid-20s

· In 2009, a couple in a similar position would have an estimated gross income of £37,000 - that’s nearly £46,000 in today’s money

· After saving for an estimated 25% deposit, they could borrow about £116,000 at an interest rate of 3.9%

· In 2009, they could buy a property costing about £155,000 - that’s roughly £192,000 in today’s money

Sources/calculations: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Savills UK, Building Societies Association, Bank of England

Even if they could have raised a deposit of more than £38,000 - and bought for £155,000 - there are slim pickings in the Evening Argus property pages.

Only about half a dozen properties in Brighton would have been affordable.

“The 2009 deposit would definitely have been a problem. The deposit is partly why we have a problem right now,” says Charlie. “People ask me why I haven’t moved out of my mother’s home. I could rent a house in 2019, but I wouldn’t be able to save. Renting and saving at the same time is totally unrealistic.”

The present day situation for first-time buyers is an intractable problem, says personal finance expert Sharon Collard.

“Some people are doing extremely well out of housing wealth, while others just can’t get on the ladder. And that seems very unfair. There are now at least eight government housing schemes aimed predominantly at helping first-time buyers. That's great, but it just kind of sums it all up doesn’t it?”

And how do Charlie and Tacita feel after their journey back in time?

“We came all the way from buying semi-detached houses to barely being able to afford a flat on a leasehold,” says Charlie.

“It seems to me that to buy in 2019, you’re either in the North - like one of my friends who has managed it - or you’re down here and you’ve been given some help from parents.”

Tacita say she is not depressed by what she learned.

“Older generations say it was just as hard back then,” she says. “But I come away from this time trip feeling almost relieved that our hunch was accurate - that we are probably the generation for whom house-buying is the hardest.”

The couple doubt they will ever be able to get on the property ladder in the south of England.

So what will they do?

“We have to look at an alternative route,” says Charlie. “We can’t afford to buy a conventional house.”

They are seriously thinking of building a so-called “tiny home” - explains Charlie - a small self-contained eco cabin, possibly on a trailer.

“Whatever we do will be a long slog,” adds Tacita. “But we hope to get benefits back in the longer term, with lower bills and no mortgage.”

LISTEN: Charlie and Tacita travel back to 2009 - when Lady Gaga, Beyoncé and Dizzee Rascal were in the charts

The figures presented to Charlie and Tacita were for illustrative purposes only.

Credits:

Words: Paul Kerley

Design and photography: Emma Lynch

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Contributors:

Charlie Chatwood and Tacita French

Jonathan Cribb - senior economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies

Prof Sharon Collard - personal finance expert from the University of Bristol

Prof Claire Langhamer - historian from the University of Sussex

Thanks to:

Lawrence Bowles - research analyst from Savills UK / Simon Rex and Hilary McVitty - Building Societies Association / The Argus, Brighton / The Keep archives, Brighton / University of Sussex / Vania Mills - Gladrags Costume Hire / Martin Carter - make-up artist / The Wig Store

Additional images:

Alamy, Getty Images, REX/Shutterstock, Brighton Argus

Additional sources:

Office for National Statistics / Resolution Foundation / Bank of England / The AA / The Met Office / UK Hydrographic Office / Zoopla / Rightmove