The Battle of Orgreave

In June 1984, striking coal miners from across Britain descended on South Yorkshire’s Orgreave coking plant in an attempt to disrupt deliveries and were met with force by thousands of police officers.

What became known as the Battle of Orgreave was a pivotal moment in the year-long miners’ strike and one of the most violent episodes in British industrial history.

Forty years on, many of those involved say they still need answers about what happened and why.

'It was about survival'

In March 1984, the National Coal Board (NCB) announced controversial plans to shut 20 UK collieries - which they said were unprofitable - with the loss of at least 20,000 jobs.

In response, more than three-quarters of the country’s 187,000 miners went on strike. The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) sent protesters - known as flying pickets - to put pressure on the miners who kept working. Margaret Thatcher’s government had previously introduced anti-strike laws which restricted picketing to employees’ places of work.

Robert Plant, miner at Ireland colliery, Derbyshire: “We were fighting for our jobs. We’d got no careers, we’d got nothing else. We needed, as a community, to stick together. It weren’t about wages, it was about survival. If there’s no jobs, there’s no money, there’s nothing."

Steve Brunt, miner at Arkwright colliery, Derbyshire and former Labour Councillor: “We’d have about 200, 250 people - sometimes as many as 350 - who came to our strike centre [to go picketing]. We used to make sure every car were full and we had a couple who drove minivans. We’d tell them where they were going and we’d give the driver petrol money and each picket received £4 a day in the early days. After about three weeks the attitude of police changed overnight. Early doors, we used to share sandwiches with them. Then all of a sudden, it was like they’d been instructed they’re not going to help us at all. Then of course road blocks started occurring.”

Lord Heseltine, minister in Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet: “A significant number of miners wanted to work and were prevented from doing so by the flying pickets… And that's a powerful argument as why the government had to make sure this sort of activity stopped.”

Don Keating, miner at Cortonwood colliery, South Yorkshire: “[My wife] Jackie says to me, ‘Don, you’re 6ft 4, you’re going to get nabbed, you’re going to get caught.’ I said, ‘No, I’m not.’ So I started going flying picketing for a couple of weeks and there was a big one at Orgreave on 18 June.”

'Scargill's Waterloo'

Arthur Scargill, president of the NUM, identified Orgreave coking plant - which supplied fuel for steel furnaces in Scunthorpe - as a key target for picketing. He believed if striking miners could prevent lorries carrying coke from the plant near Rotherham, the steelworks would have to shut down and the government would be forced to negotiate an end to its dispute with the NUM.

From 22 May, miners were sent each day to picket the plant - which they were blocked from reaching by a growing wall of police. Officers were deployed from forces around the country to repel picketers, who the government accused of intimidating people who wanted to work.

Steve Brunt: “We just went there to do a job, we’d been sent there to try and stop them lorries getting into that plant. We used to have a push at the police, they’d push back, we’d push again and then we’d go home. Eventually it developed into a lot more than that. That’s when the violence started and after about three or four days it started to get really violent.”

Richard Wells, reporter for BBC Look North: “That was, I suppose, Scargill's [Battle of] Waterloo. That was where the strike was going to be won or lost, effectively.

"Every day the tension was a little bit more than the day before and the miners were not stopping those lorries from taking their coking coal into Orgreave. So tension built and frustration built.”

Bruce Wilson, miner at Silverwood colliery, South Yorkshire: “To start with there were ordinary policemen in uniform. But by the end of May they’d replaced them with riot squads - short shield and long shield. They’d just open up and literally charge at miners. Some days it was like that film, Zulu. It was a bit intimidating.”

Ali Modak, Humberside Police officer: “I was marching along with the rest of my colleagues and suddenly there was a bang on my head and when I took my helmet off there was a big gouge in it. I think it was a big heavy piece of flint that hit my helmet. If it was a normal helmet I probably would have been knocked out.

"It was violent on both sides. You could understand it from the miners’ side, they were going to lose their livelihoods, jobs and what have you. The police, some of them, especially from out of the area, they were heavy-handed.”

Steve Brunt: “I know 18 June was a big day, it was a huge battle. But it was a battle most days. Orgreave was awful at times, it was shocking.”

'Lambs to the slaughter'

Tensions at Orgreave came to a head after Scargill called for a mass picket of the coking works on 18 June. On a blazing hot summer’s day, miners were bussed to South Yorkshire in their thousands by the NUM. Police were prepared: an estimated 6,000 officers - some on horseback, others with dogs or riot shields - formed a cordon around the plant.

Hilary Cave, former NUM education officer: “They were making plans in Arthur's [Scargill’s] office for weeks beforehand, but I wasn't involved in that, and none of them would say anything about it. But it seems that there was a sort of plan as to where people would be deployed. I don't know how the police knew what the plan was but they were putting us where they wanted us, not where the plan was for us to go.”

Russell Broomhead, miner at Houghton Main colliery, South Yorkshire: “When we got there it was surreal because there was no attempt to stop us. In fact, police showed us where to park and everything - which I couldn't quite believe. We should have clicked that something was going to go off.”

John Dunn, miner at Markham colliery, Derbyshire: “All of sudden pickets were allowed to get to the picket line. We’d got rings of steel around our villages that stopped us going there, but [at Orgreave] they even provided parking. It was the biggest set-up.”

Robert Plant: “There were lots of police - God knows how many - on horseback, with dogs, riot shields and truncheons. It was like they were preparing for battle and we were going to be like lambs to the slaughter.”

Chris Kitchen, miner at Wheldale colliery, West Yorkshire: “Just lines of coppers. A wall of riot shields. Lines of coppers and then more coppers behind them with all the vans and the police horses and you’re thinking, this is different, they’ve come prepared.”

The Charge

A convoy of 35 lorries arrived at Orgreave at 08:10 to collect the day’s first shipment of coke. Miners briefly pushed against police - as was the ritual on picket lines - until the lorries had passed. At 08:20, the police lines parted and mounted officers charged into the field.

Assistant Chief Constable Anthony Clement, who was in operational control of South Yorkshire Police’s operation, said mounted police were used to disperse miners throwing a “barrage of missiles”, but prosecutors later conceded in court that most projectiles were thrown after the police charge.

Robert Plant: “We were pushed up to the riot shields, there was a lot of people pushing us into the shields. I says we need to get out of here. I think somebody had thrown a stone from the crowd, I says I don’t really like that because all that’s doing is antagonising the police, so let’s just go out the way.”

Tony Munday, Hertfordshire Police officer: “At some point, there was a hell of a lot of bricks and other things being thrown in our direction. My main concern was just to look down to the ground because I didn't want to be blinded. I said ’I hope someone is going to do something soon because this isn’t a good place’. We were almost like skittles, completely defenceless.”

Chris Kitchen: “There were some throwing from lads further back than us. There were no way that them missiles were going to the police lines. They had more chance of hitting us.”

Russell Broomhead: “There were people at the back throwing stones and that, and they were actually hitting us [miners]. So I turned around, and I got me back to the police lines, and I'm shouting ‘Give over throwing, you're going to hurt us.’ Then everybody scattered. I turned around and there was this police horse nearly on top of me.”

Paul Brown, South Yorkshire Police mounted officer: “The pickets were getting really agitated and it was decided to relieve the pressure on the lines to bring us forward… I was quite lucky, I ducked and dived at quite a few of the missiles.”

Robert Plant: “The horses came galloping through and they trampled this guy about five or six metres from me, four horses just flattened him. So I shouted a few abusive words to them, I weren’t happy, and they just carried up going up the field.”

Tony Munday: “[When] officers on horseback went through followed by officers with short shields we actually cheered because it wasn’t a good place to be, it really wasn’t, when you’ve got no protection… Not knowing what the strategy was of the people in charge, we're thinking, frankly, 'Are we just cannon fodder?' You had no idea.”

Steve Brunt: “I went round the corner, I’ve got a horse behind me and one coming towards me. I thought I have no idea where I’m going. All I remember is going down on the ground and I must have gone under the horse's legs or very close to them. We went down the banking, across the railway, up the other side and then turned round and looked and there’s police stood there with them little batons. They were banging them just like the Zulus were banging them shields in that film: bang, bang, bang.”

Chris Kitchen: “The excitement that I felt when we first got there of being part of something that were much bigger than I’ve ever been on before soon turned to fear. You started to realise that we’re here to peacefully picket and we’ve got the numbers but we’ve got no protection and the police were tooled up. They came prepared. They knew what were going to happen.”

'Set us up'

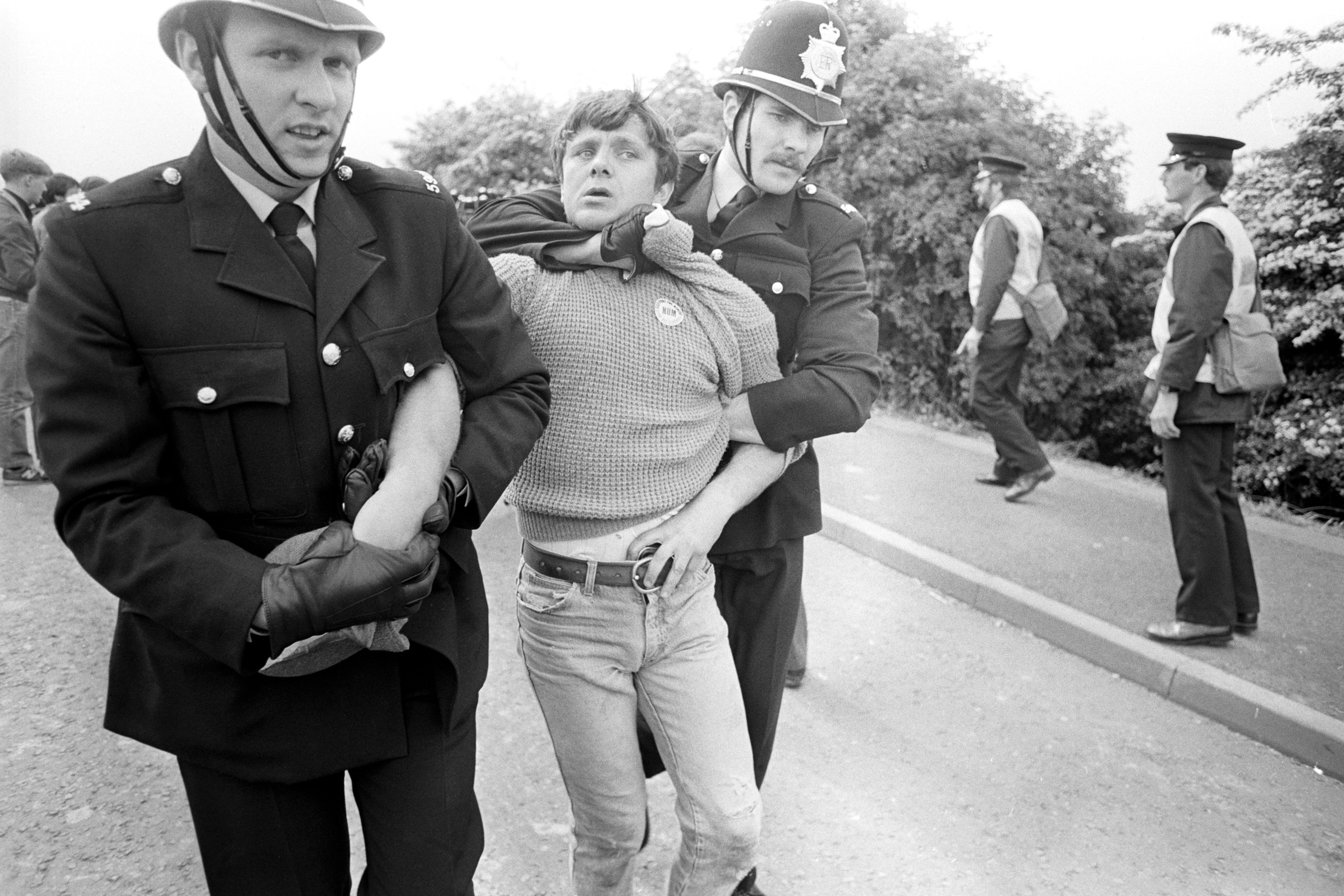

Mounted officers briefly returned behind police lines before charging at picketers again at 08:35, followed by specialised short shield units known as "snatch squads". As miners fled charging police horses, some were set upon by officers who had been ordered to clear the field of picketers.

Don Keating: “Somebody got hold of me by the hair and dragged me to the ground. Before I knew it, there was four coppers on me. One had got his lock around my neck. I genuinely thought I was going to die, I just could not breathe. I made him aware and - to give him his due - he did ease off and he carried me to the bus and handcuffed me.”

Robert Plant: “I’m looking round and the next thing I got arrested by the snatch squad. I don’t know what they said to me, it were very noisy. Two of them with truncheons. No point in putting up a fight.”

Don Keating: “It was bloody scary. I’m no wimp but I’m not a scrapper either. I’d been through a few situations [as a soldier] in Northern Ireland in 1969 and we had a lot of rioting there … But to have four of them around you and one of them around your neck…”

John Dunn: “People had gone in shorts, T-shirts and trainers just to picket, enjoy the sun and then go home. And what did they get? They got savagery on an unseen scale.”

Steve Brunt: “They [the police] had geared up for that, they set us up. And they set us up to fail and get battered. Looking back, that’s the way I see it.”

'Barbaric'

Cameras captured Russell Broomhead, pictured below in red, being repeatedly hit on the head by police with truncheons.

Russell Broomhead: “I turned around and there was this police horse nearly on top of me. So I went flying, and as I were getting back up the police came back with truncheons and shields, and that's when they got me. He just battered me. I couldn’t believe a human being could be so wrong to another human. He seemed to be enjoying it.”

Steve Brunt: “The horses had knocked him [Russell Broomhead] over and then from the side this officer came up, just grabbed him and started walloping him - it was barbaric, the brutality. I’d got a lad at the side of me, and we looked at each other and said ‘Are we going to give him a hand?’ And all of a sudden the horses charging and the men coming up behind answered our question: no, not now. We just legged it.”

Russell Broomhead: “I was quite badly bruised especially on the back of my head and my shoulders. I’d got a cut on my head … They took us to hospital, we were checked over and told we were OK. They took us to Snig Hill police station [in Sheffield], we were locked up there.”

'Carnage' in the village

Fleeing picketers were pursued by police into the village of Orgreave, where officers hit miners with truncheons and made arrests. Some miners dismantled a stone wall for a makeshift road block and set alight a car from a nearby scrapyard.

Hilary Cave: “We were standing just at the village side of the railway bridge. As soon as we stopped retreating the police line just parted and these horses galloped through. Well, you don't stand your ground in those circumstances unless you want to get killed. We turned and ran, terrified.”

Bruce Wilson: “We were chased by riot squads. It was a red hot day and I remember this old miner, he must have been 55, 60, and he was on his knees, he was gasping for breath. He’d got a long coat on. I looked behind me at the riot squad, they were getting closer. I looked at this old bloke and I put my arm round his and I says, ‘Come on old lad, get up, they’re not taking any prisoners today’. I don’t know where he got strength but we both started running again.”

Injuries and arrests

At least 120 miners and police officers were injured in the violence. Ninety-five picketers were arrested.

Russell Broomhead: “When they led us through the police lines to the detention centre they were all in a line waiting to kick you. By that stage they were out of control, totally out of control. It’s a good job they weren’t armed or they’d have killed somebody that day. They’d have shot somebody.”

Robert Plant: “They either kicked you or they punched you. I got kicked on the knee, so I suppose I were quite lucky.”

Paul Brown: “I’m of the belief that we are a disciplined unit and I can’t believe any police officer would want to seriously injure or cause damage to another human being. But the adrenaline is pumping and you can only stand so much before somebody sees a little bit of red mist.”

Robert Plant: “Later on, in the queue, there was a guy in front of me being beaten by the police. One of them got him in a headlock, the other guy was pushing his shoulder down, and I counted 40 punches to the face. My legs were going a bit rubbery, I thought is it me next? Another [officer] I think it was a police inspector said ‘I think he’s had enough sir’. [He replied] ‘I’ve not finished with him yet,’ so he hit him again and rammed his head into the bottom of the stairwell. Which was just sheer brutality, there was no need for that.”

'Fit people up'

Fifty-five men arrested at Orgreave were charged with riot, which at the time could be punishable with a life sentence. A further 40 were charged with unlawful assembly. But their trials later collapsed when police evidence was deemed unreliable. Police officer Tony Munday, who had detained a picketer for obstruction, recalled being ordered to include false evidence in his arrest statement in order to substantiate a riot charge.

Tony Munday: “We sit down at desks, like school desks, and started to write the statement - I was well-versed in making a statement. Someone in plain clothes came in - a senior officer from South Yorkshire - and said, 'Stop writing. Right, we need you to open your statement with these couple of paragraphs'. And then I said, 'What's this all about? That's not how it's done. I’ll write my own statement'. There were others who said it as well. [The officer said:] 'This isn't a request, this is an order'. He then started dictating and I could tell what was being dictated were the ingredients of the offence of riot. The words were written, to use the vernacular, to fit people up. That’s what it was.”

Robert Plant: “I was charged with riotous assembly. I was a riot leader, apparently. Me, a riot leader? I was on my own, all my friends had left me. I was stood on my own, I just got snatched and taken away. I couldn’t believe it.”

Don Keating: “We knew we weren't guilty of rioting. Yes we were noisy, yes were boisterous, but I can honestly say I never threw a brick, I never hit a copper. My arrest was totally unjustified. It was a way of keeping pickets off the picket line.”

Robert Plant: “It was very worrying and harrowing to think you could have a life sentence. I was only 27, and I was thinking I’m going to get jailed for demonstrating about trying to save my job.

"It was life-changing, because after the strike it made me very bitter. How we were treated, it were really wrong. Loads of people were black-listed and didn’t get jobs.”

Don Keating: “I’d got a wife and two young children, so that was a big worry, especially when they changed it to riotous assembly. I was a bit concerned about what the sentence could be if I was found guilty. That scared me more than anything.”

The Aftermath

South Yorkshire Police paid a total of £425,000 in damages to 39 miners who sued over assault, unlawful arrest and malicious prosecution. The force did not admit wrongdoing and no officers have faced misconduct proceedings or prosecution. In 2015, an Independent Police Complaints Commission review concluded there was evidence some officers deployed at Orgreave had committed perjury and assault, and perverted the course of justice.

The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign continues to campaign for a public inquiry into the events, but neither the Conservatives nor Labour has announced one while in government.

Chris Kitchen: “A lot of people, myself included, need to hear what the plan was on that day. I know at the back of my mind what happened, I were there, I saw it. I’ve no doubt it was planned but I want to know how high up did it go? Was it actually spoken about at cabinet level, or ministerial level. Who colluded into it? Who turned a blind eye to it?”

Lord Heseltine: “Why do we need an inquiry? It's all on the television screens… It may be a field day for the lawyers, and anyone who's got strong views would come out believing that their views had been either ignored or supported. There's absolutely nothing to be said for going over this issue [which has been] exhaustively explored time and time again.”

John Dunn: “I’ve spent 40 years trying to clear my name from the frame-up that occurred. We want an inquiry into what happened on that day, not just to prove that pickets weren’t the perpetrators of violence - that it was police - but also if we can get an inquiry into that we can shine a light into all that happened for all those 12 months.”

Tony Munday: “The question is why, now, after 40 years are we still waiting? Because the essence of this for me is this: this was clearly corrupt behaviour by South Yorkshire Police. And four years later the same force were involved with [the disaster at] Hillsborough. If this had been dealt with properly, and by properly I mean a criminal investigation [into police conduct], who knows what may or may not have happened at Hillsborough?”

In a statement provided in June 2024, South Yorkshire Police said: "It would not be appropriate for the South Yorkshire Police of today to seek to explain or defend the actions of the force in 1984 as everyone involved in policing the miners’ strike has long since retired and the information we hold has not been properly assessed.

"We have been very clear about our intent to make as much of the relevant documentation as is possible available to the public. To that end, a small team, funded by the then Police and Crime Commissioner, is reviewing and cataloguing all of the material held by the force and ensuring anything released is done so in line with the requirements of GDPR. There are 1,474 files of material which amount to 82,913 pages.

"When this work is complete, we will seek to follow the process undertaken by both the Home Office and the Cabinet Office, and place the documents in a recognised public archive. This is expected to take up to another 18 months to two years."

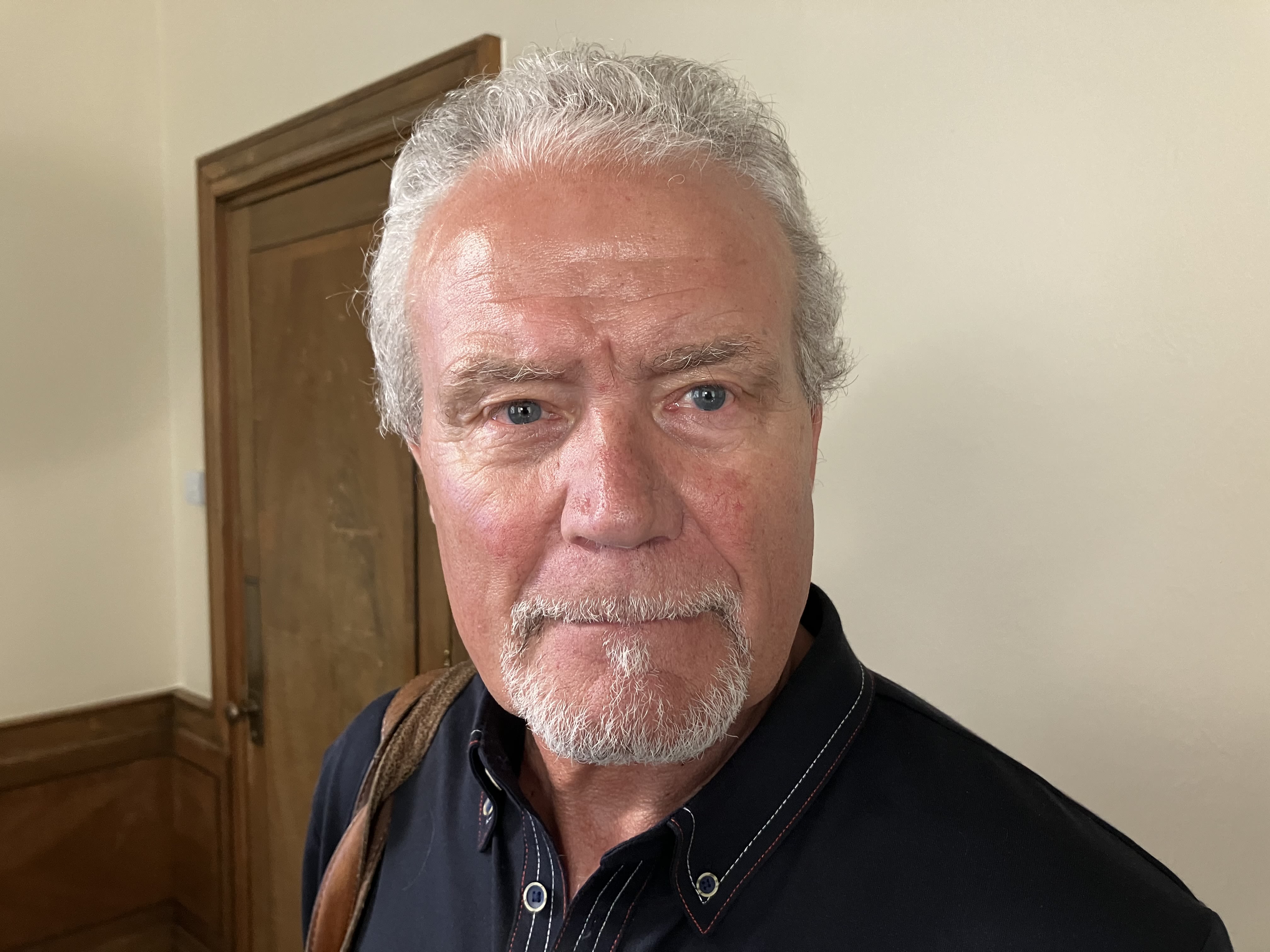

Robert Plant

Steve Brunt

Chris Kitchen

Bruce Wilson

Russell Broomhead

Don Keating

Hilary Cave

John Dunn

Tony Munday

Paul Brown

Credits:

Interviews by:

Chris Baynes, Joanne Carter, Steph Miskin

Editors:

Hayley Brewer, Ed Barlow

Sub:

Adam Jones

Archive Images:

Getty

Online Production:

England Data and Formats Unit