The ones they couldn’t save

By Alison Holt

It’s the early hours of the morning and Michelle Heavens moves quickly along one of the care home’s dark corridors.

She’s the senior carer on duty overnight and needs to check on 84-year-old Joan Day. Michelle pauses to put on a mask, goggles, apron and gloves before going into Joan’s room.

Joan has coronavirus and is going downhill fast.

“I loved her from the day she came in,” says Michelle.

Joan had been physically fit, but dementia had made her life increasingly difficult. She'd moved into the specialist home at Blackley in Manchester last year and settled in quickly.

“She was always singing Joan. Absolutely brilliant lady. She’d ask us if we needed help, rather than us give her any support.”

Michelle checks Joan’s oxygen levels. They’re dropping rapidly. She’s having difficulty getting her breath so Michelle and two other carers reposition her to try to make her more comfortable. The nurse also gives her painkilling drugs.

Joan Day

By early morning, it’s clear Joan is not improving.

Normally her family would be with her, but coronavirus restrictions mean they haven’t seen her for weeks.

Joan’s daughter, Yvonne Connelly, is herself shielding. Carers are her only link to what’s happening in the home.

Shortly before finishing her shift, Michelle calls Yvonne. She explains that Joan’s health is deteriorating.

“There’s not much else I can say, apart from she’s not coming back from it.”

Yvonne wants to speak to her mother on the phone, but Joan is too ill.

“When Michelle called she was lovely about it. She was upset herself,” reflects Yvonne. “She said ‘Yvonne, I don’t think she’ll be here when I come back tonight.’”

Just a few hours after that call, Joan died.

Yvonne was devastated she couldn’t be at her mother’s side.

“It’s the worst feeling in the world.”

Across the UK, more than 22,000 care home residents have died with Covid-19.

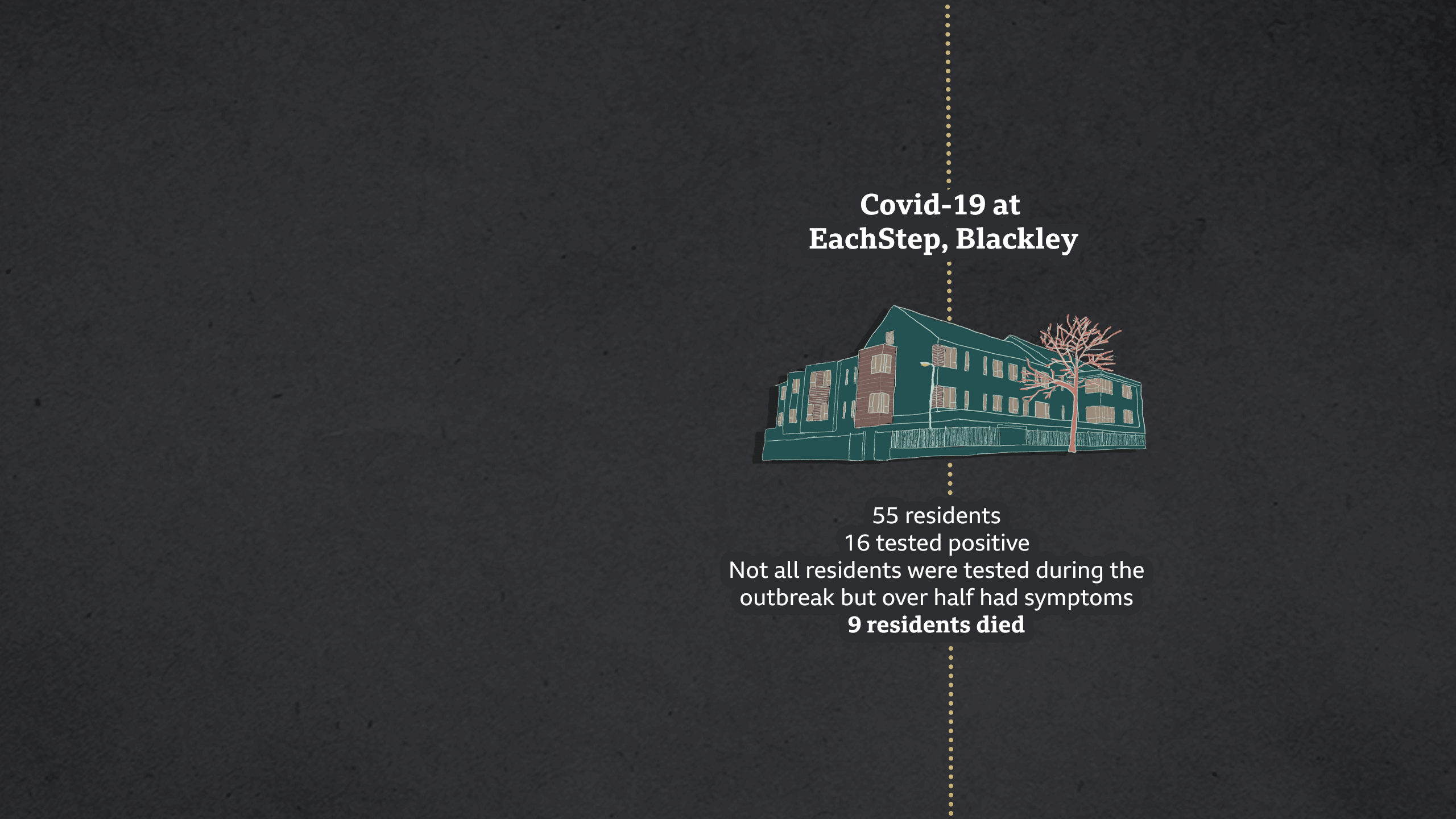

Joan Day was one of nine residents to die with the virus at EachStep Blackley - one of two care homes that granted Panorama access during the pandemic.

Nurse Phil Benson had heard about a new virus emerging in China on the news, but it seemed a world away. “I was naive about it initially. It didn’t seem like it was a real thing. Nothing to worry about.”

Phil’s a dementia specialist working for Community Integrated Care, the charity that runs EachStep Blackley. In the past, he’s worked in A&E and intensive care.

“Social care’s probably the most challenging job I’ve ever had, but the best as well. It all starts from the heart.”

Phil Benson

But that “heart” was soon to be tested beyond measure, in a care sector already struggling with growing demand from an ageing population and years of underfunding.

- 22 Jan - Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) first meeting

- 10 Feb - “Realistic probability” of sustained virus transmission in UK, or that it will “become established” in coming weeks, advises Sage

- 11 Feb - Novel coronavirus disease named Covid-19

On 23 January, 11 million people were locked down in the Chinese city of Wuhan. A picture was emerging of a new illness that was particularly worrying for older people and those with underlying health conditions.

As the virus started to spread globally, the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies - Sage - held regular meetings and fed advice to ministers.

Sage brought together a wide range of experts plus food supply strategists, those with digital marketing experience and even staff from the justice system.

But no-one had specific expertise in old age or social care.

During February, Sage spent a lot of time planning how the NHS would cope. There were also two discussions about preventing the virus spreading in prisons.

More than 400,000 people live in care homes in England, but according to official minutes, care homes didn’t appear on the agenda for the first 11 meetings.

“It remains very unlikely that people receiving care in a care home or the community will become infected… There is no need to do anything differently in any care setting at present” was the Public Health England and government advice on 25 February.

- 2 Mar - UK’s first Covid-19-related death

- 3 Mar - First mention of care homes at Sage meeting

- 6 Mar - First two care home deaths

On 3 March, Phil heard about a major virus outbreak at a care home in Seattle in the US. Thirty-seven people would eventually die.

“The guy speaking about Seattle said it was spreading from room to room, despite them using the best technologically available PPE [Personal Protective Equipment].

“I was thinking, oh my God, it can’t be, this is going to devastate us.”

It was also the day Sage scientists discussed care homes for the first time. In a discussion about social distancing for over-65s the minutes note that: “It will be a challenge to implement this measure in communal settings, such as care homes.”

At a televised briefing, England’s Chief Medical Officer, Prof Chris Whitty said there would be “specific advice for care homes, but they didn’t want to do it too early”.

But it already felt too late for Mark Adams, Phil’s boss and head of the charity Community Integrated Care.

Mark Adams

“We set up our own war room. We made our own decisions about what we could do to protect people.”

Ordering PPE for many care homes was also a major problem. They claimed some of their usual supplies were being diverted to the NHS and the price of masks, aprons and gloves had skyrocketed.

Community Integrated Care locked down all its homes on 13 March, including EachStep Blackley. Family and friends could no longer visit.

The same day, the government withdrew advice which said the virus spread in care homes was unlikely. It said no-one with suspected Covid-19, or who was unwell, should visit care homes.

Nurse Phil Benson had heard about a new virus emerging in China on the news, but it seemed a world away. “I was naive about it initially. It didn’t seem like it was a real thing. Nothing to worry about.”

Phil’s a dementia specialist working for Community Integrated Care, the charity that runs EachStep Blackley. In the past, he’s worked in A&E and intensive care.

Phil Benson

“Social care’s probably the most challenging job I’ve ever had, but the best as well. It all starts from the heart.”

But that “heart” was soon to be tested beyond measure, in a care sector already struggling with growing demand from an ageing population and years of underfunding.

- 22 Jan - Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) first meeting

- 10 Feb - “Realistic probability” of sustained virus transmission in UK, or that it will “become established” in coming weeks, advises Sage

- 11 Feb - Novel coronavirus disease named Covid-19

On 23 January, 11 million people were locked down in the Chinese city of Wuhan. A picture was emerging of a new illness that was particularly worrying for older people and those with underlying health conditions.

As the virus started to spread globally, the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies - Sage - held regular meetings and fed advice to ministers.

Sage brought together a wide range of experts plus food supply strategists, those with digital marketing experience and even staff from the justice system.

But no-one had specific expertise in old age or social care.

During February, Sage spent a lot of time planning how the NHS would cope. There were also two discussions about preventing the virus spreading in prisons.

More than 400,000 people live in care homes in England, but according to official minutes, care homes didn’t appear on the agenda for the first 11 meetings.

“It remains very unlikely that people receiving care in a care home or the community will become infected… There is no need to do anything differently in any care setting at present” was the Public Health England and government advice on 25 February.

- 2 Mar - UK’s first Covid-19-related death

- 3 Mar - First mention of care homes at Sage meeting

- 6 Mar - First two care home deaths

On 3 March, Phil heard about a major virus outbreak at a care home in Seattle in the US. Thirty-seven people would eventually die.

“The guy speaking about Seattle said it was spreading from room to room, despite them using the best technologically available PPE [Personal Protective Equipment].

“I was thinking, oh my God, it can’t be, this is going to devastate us.”

It was also the day Sage scientists discussed care homes for the first time. In a discussion about social distancing for over-65s the minutes note that: “It will be a challenge to implement this measure in communal settings, such as care homes.”

At a televised briefing, England’s Chief Medical Officer, Prof Chris Whitty said there would be “specific advice for care homes, but they didn’t want to do it too early”.

But it already felt too late for Mark Adams, Phil’s boss and head of the charity Community Integrated Care.

Mark Adams

“We set up our own war room. We made our own decisions about what we could do to protect people.”

Ordering PPE for many care homes was also a major problem. They claimed some of their usual supplies were being diverted to the NHS and the price of masks, aprons and gloves had skyrocketed.

Community Integrated Care locked down all its homes on 13 March, including EachStep Blackley. Family and friends could no longer visit.

The same day, the government withdrew advice which said the virus spread in care homes was unlikely. It said no-one with suspected Covid-19, or who was unwell, should visit care homes.

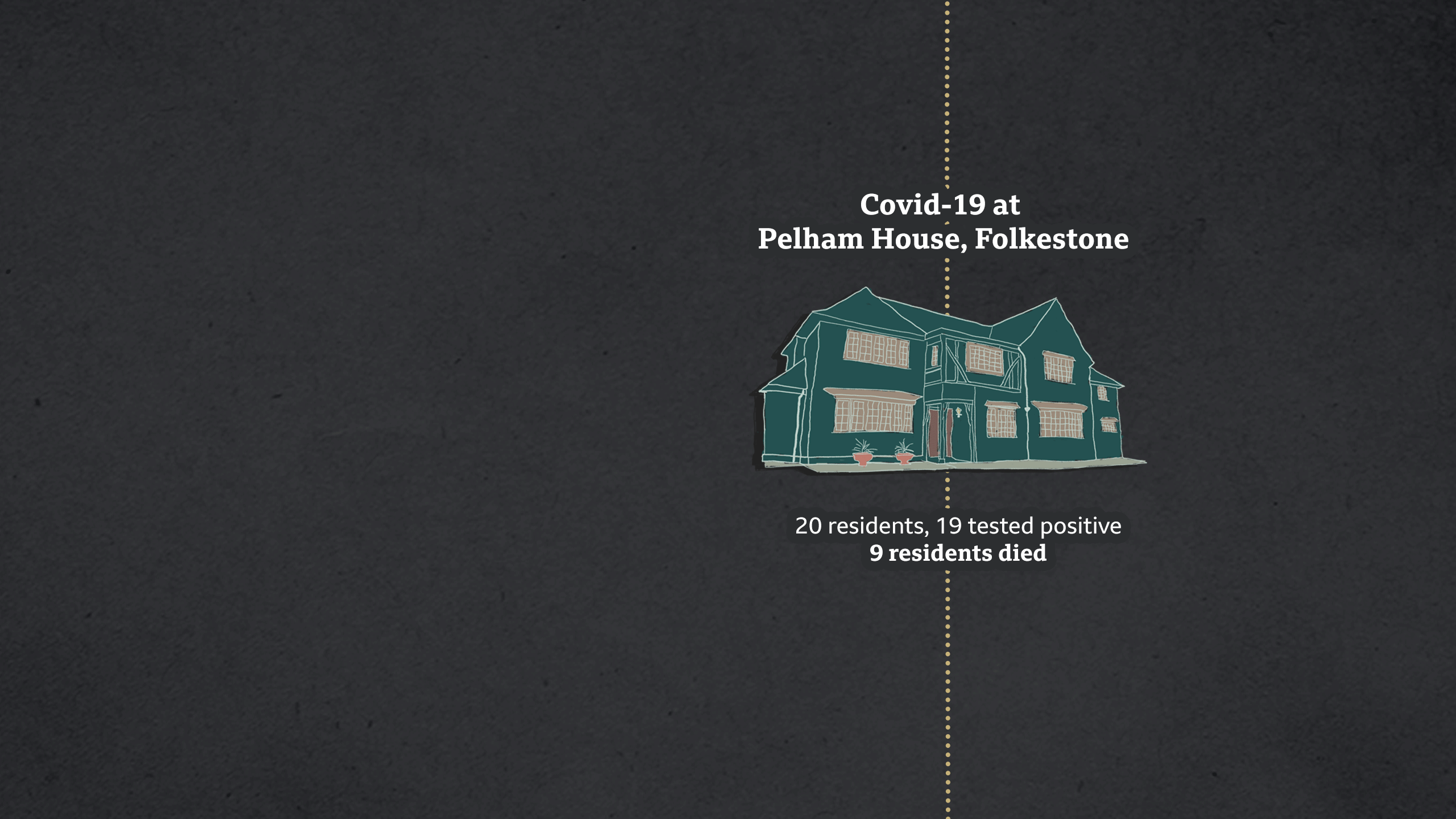

More than 200 miles away in Kent, at Pelham House in Folkestone, they were also worrying about how they would deal with the virus. A small, privately-run dementia home looking after 20 people, Pelham, like Blackley, also allowed Panorama in during the pandemic.

Pelham’s owner, Roger Waluube, locked down on 16 March.

“At that stage we began to get reports Covid was here on our doorstep,” says Roger. “We had to keep the wolf at bay.”

Roger Waluube

That evening, at the first 5pm Downing Street daily briefing, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said no-one should make “unnecessary” visits to care homes - but he stopped short of saying people must not visit relatives under any circumstances.

By mid-March, the number of people needing treatment for Covid-19 in hospitals was rising rapidly.

On the 17 March, NHS England sent hospitals a letter saying all medically-fit patients should be discharged as soon as possible. There was no requirement for testing.

- 12 Mar - UK stops contact-tracing programme

- 13 Mar - “If neither the care worker nor the individual receiving care and support is symptomatic, then no personal protective equipment is required above and beyond normal good hygiene practices” - Public Health England guidance

- 16 Mar - Boris Johnson hosts first 5pm daily briefing

- 16 Mar - World Health Organization calls on countries to escalate testing, isolation and contact tracing

- 17 Mar - NHS England tells hospitals to free up beds

During the next four weeks, 25,000 patients were discharged to care homes. Panorama has gathered data from 39 hospital trusts, which shows three-quarters of people discharged were untested.

The social care system is run by local councils, not the NHS. In all parts of the UK it’s under pressure from an ageing population and funding cuts.

James Bullion was just taking over the role as president of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), representing officials who run council care services in England.

When he and colleagues met the prime minister and the Health and Social Care Secretary, Matt Hancock - he says making sure the NHS could cope was the overriding message.

“There was a very strong feeling that anything that got in the way of that discharge arrangement [from hospitals] needed to be got out of the way.

“Social care, the NHS and government should have had the forethought to think ‘It’s not right to discharge people without a test,” he says.

Panorama: The forgotten front line

BBC One at 21:00 on Thursday 30 July

Or watch on iPlayer

NHS England says testing policy is set by ministers and it has never supported pressure being put on care homes to accept admissions.

The government has also repeatedly said that hospital discharge decisions during this time were made by medical professionals on a case-by-case basis.

Sage advisers have since said residents moving into and out of hospital “may have been an important source” of the introduction of Covid-19 into care homes.

More than 200 miles away in Kent, at Pelham House in Folkestone, they were also worrying about how they would deal with the virus. A small, privately-run dementia home looking after 20 people, Pelham, like Blackley, also allowed Panorama in during the pandemic.

Pelham’s owner, Roger Waluube, locked down on 16 March. “At that stage we began to get reports Covid was here on our doorstep,” says Roger. “We had to keep the wolf at bay.”

Roger Waluube

That evening, at the first 5pm Downing Street daily briefing, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said no-one should make “unnecessary” visits to care homes - but he stopped short of saying people must not visit relatives under any circumstances.

By mid-March, the number of people needing treatment for Covid-19 in hospitals was rising rapidly.

On the 17 March, NHS England sent hospitals a letter saying all medically-fit patients should be discharged as soon as possible. There was no requirement for testing.

- 12 Mar - UK stops contact-tracing programme

- 13 Mar - “If neither the care worker nor the individual receiving care and support is symptomatic, then no personal protective equipment is required above and beyond normal good hygiene practices” - Public Health England guidance

- 16 Mar - Boris Johnson hosts first 5pm daily briefing

- 16 Mar - World Health Organization calls on countries to escalate testing, isolation and contact tracing

- 17 Mar - NHS England tells hospitals to free up beds

During the next four weeks, 25,000 patients were discharged to care homes. Panorama has gathered data from 39 hospital trusts, which shows three-quarters of people discharged were untested.

The social care system is run by local councils, not the NHS. In all parts of the UK it’s under pressure from an ageing population and funding cuts.

James Bullion was just taking over the role as president of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), representing officials who run council care services in England.

When he and colleagues met the prime minister and the Health and Social Care Secretary, Matt Hancock - he says making sure the NHS could cope was the overriding message.

“There was a very strong feeling that anything that got in the way of that discharge arrangement [from hospitals] needed to be got out of the way.

“Social care, the NHS and government should have had the forethought to think ‘It’s not right to discharge people without a test,” he says.

Panorama: The forgotten front line

BBC One at 21:00 on Thursday 30 July

Or watch on iPlayer

NHS England says testing policy is set by ministers and it has never supported pressure being put on care homes to accept admissions.

The government has also repeatedly said that hospital discharge decisions during this time were made by medical professionals on a case-by-case basis.

Sage advisers have since said residents moving into and out of hospital “may have been an important source” of the introduction of Covid-19 into care homes.

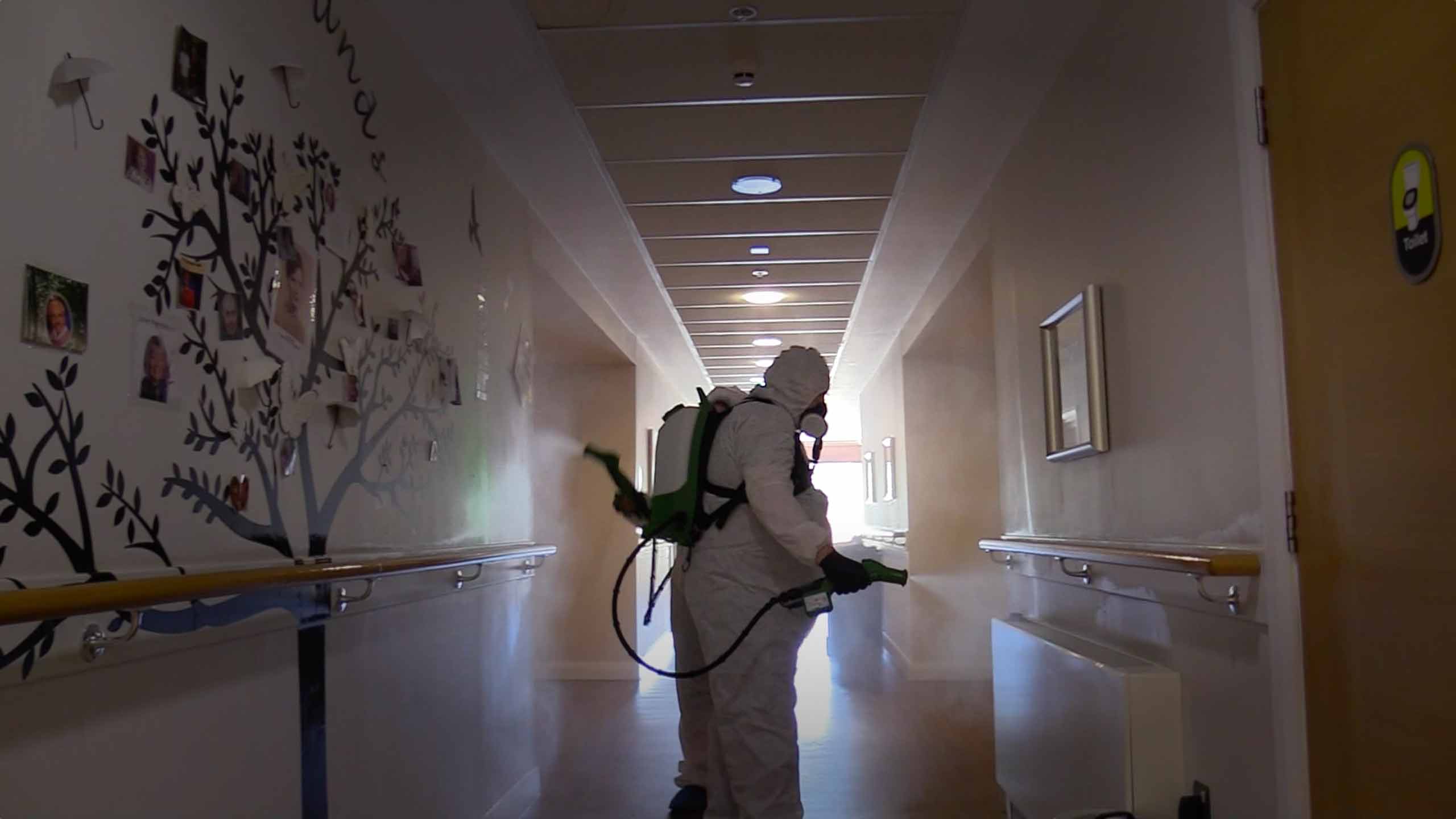

On 23 March, as the national lockdown began and streets fell eerily quiet, Phil Benson was on standby for the first coronavirus outbreak at a home run by Community Integrated Care. “I remember at that time the anxiety building,” he says.

That week, there would be more than 500 outbreaks of coronavirus in care homes in England.

On the last day of March, Phil got the call. EachStep Blackley had an outbreak.

- 23 Mar - Boris Johnson announces wider lockdown

- 23 Mar - MPs raise concerns in the Commons that some care homes are still allowing visits while others are worried about admitting residents discharged from hospital

- 25 Mar - “Carers are distraught they have to work with little or no PPE” - GMB union

A resident, who’d been in hospital with breathing problems, had tested positive. She was very poorly and returned to the home for her last few days.

“It was scary. We didn’t know much about Covid at that point,” says Debra Fielding, one of the advanced carers.

“She came in through the back way, straight into an end bedroom. No residents were near her. Only certain staff were going in, they had to wear special PPE - visors, goggles, aprons, gloves.”

Debra Fielding

Other Blackley residents had started showing Covid-19 symptoms before she returned, but she was the first to die with the virus.

In Kent, staff at Pelham House felt they were doing well keeping the virus out. Eighty-seven-year-old Doreen is one of the residents. She moved in after being diagnosed with dementia. She misses her late husband and old home. She has some understanding of what’s going on.

“Coronavirus - that’s something that if you’ve got it, you must stay isolated,” she says. “It’s a bit frightening.”

Doreen

Pelham House, like many homes, was struggling to get enough PPE. Even basics, like food, were problematic - with the home’s regular supplier stopping deliveries.

As a small care home, we were “left alone and set adrift, if I’m honest”, says Roger Waluube.

At Blackley, they checked residents’ temperatures, oxygen levels and blood pressure four times a day. They even brought in air purifiers, but the virus was spreading. In the two weeks after their first confirmed case, five died and 14 were showing symptoms.

But none of those deaths were reflected at the televised daily government briefings. For the first six weeks, graphs that ministers and scientists pointed to - showing the number of coronavirus deaths - only showed what was happening in hospitals. Care home numbers were not included.

Hospital deaths linked to Covid-19 peaked in England on 8 April. The peak in care homes followed soon after.

- 2 Apr - Updated guidance from Department for Health and Social Care:

“Family and friends should be advised not to visit care homes, except next of kin in exceptional situations such as end of life”

“Negative [coronavirus] tests are not required prior to transfers/admissions into the care home”

“Respirators, fluid-resistant surgical masks, eye protection... can be subject to single sessional use - for example, a ward round or taking observations of several patients”

- 8 Apr - Peak of covid-related hospital deaths in England and Wales

- 10 Apr - “We are working around the clock to ensure those working in social care are receiving the PPE they need” - government's PPE action plan

Behind the scenes, directors of councils care services were increasingly worried.

On 11 April, they sent a strongly worded letter to the Department of Health and Social Care. Social care appeared an afterthought, it said, adding that government guidance was contradictory and PPE distribution shambolic.

The letter was leaked.

James Bullion, ADASS president, says they were “distressed” by their “emotive” message going public, but it was an exceptional time.

“We were frustrated by the lack of grip of the PPE issue, and lack of understanding about how you get, effectively, PPE to thousands of local organisations,” he says.

The government says over the course of the pandemic it has provided 156 million items of protective equipment to social care.

At Blackley, staff were particularly worried about 85-year-old Bryan McHugh. A resident for two-and-a-half years, he had a history of lung problems. His daughter, Susan Murray, smiles at photos of Bryan with his grandson. “He was just lovely. He’d do anything for anybody. Nothing was ever too much trouble.”

On 15 April, the home told her father had Covid symptoms. The following day he deteriorated.

It took more than two hours for an ambulance to arrive. By then, Bryan was in a lot of pain and struggling to breathe.

Advanced carer, Chelsea Mills, says it was tough.

“To watch someone in pain is absolutely horrendous when you feel helpless. It was extremely hard.”

Chelsea Mills

There were difficult discussions between paramedics, Blackley staff and Bryan’s family about what to do for the best.

Bryan was dying and being in hospital would not save him. It was agreed he should remain in the home surrounded by people he knew.

His daughter Susan had asked the carers to give him a message.

“Just tell him there’s Covid outside. We’ve got to be isolated in our own homes. That’s why we can’t come. And just tell him that we love him.”

On the night shift, experienced nurse Herbert Mumbamarwo gave Bryan prescribed painkilling drugs - including morphine - but they weren’t working.

Herbert Mumbamarwo

“Bryan over the last 10 to 12 months has never spoken a complete sentence,” says Herbert. “But that night, he managed to say ‘I can’t breathe, I’m drowning,’ words I didn’t know he could speak. That explains the extent of the trauma he was experiencing.”

In a hospital, Herbert could have turned to senior doctors for advice to make Bryan more comfortable in his final hours, but in the care home he was the only medically-trained person on duty.

“I was going on YouTube, on NICE guidelines, trying to find better ways to help. It didn’t help much. After my shift, I had a feeling of… I’ve failed Bryan.”

Bryan was more comfortable by morning, but died the following night.

Family photo: Susan, Bryan and his wife Sheila

“I feel as though I’ve let my dad down,” says daughter Susan. “Not being able to hold his hand was just horrendous. He relied on me, he used to say he always wanted me there if he was poorly.”

NHS England says care homes had medical support through the pandemic.

Herbert understands the whole system was under pressure, but believes there are still lessons to learn.

“We would benefit from a team of specialists, specifically on standby to respond to extreme cases of Covid. They could give advice on what best to do.

“We’re not defying death, but what we’re trying to do is our mission statement - to make it comfortable.”

In the week Bryan died, care home deaths peaked.

More than 3,300 residents died in England and Wales. At its worst, 540 died in a single day.

It’s a situation that angers Mark Adams from Community Integrated Care - the charity that runs EachStep Blackley.

“Nobody really thought about the challenge that care organisations were going to face until, if I’m being brutal, the body count became so high they couldn’t ignore it.”

At Blackley, staff were particularly worried about 85-year-old Bryan McHugh. A resident for two-and-a-half years, he had a history of lung problems. His daughter, Susan Murray, smiles at photos of Bryan in the garden with his grandson. “He was just lovely. He’d do anything for anybody. Nothing was ever too much trouble.”

On 15 April, the home told her father had Covid symptoms. The following day he deteriorated.

It took more than two hours for an ambulance to arrive. By then, Bryan was in a lot of pain and struggling to breathe.

Advanced carer, Chelsea Mills, says it was tough.

“To watch someone in pain is absolutely horrendous when you feel helpless. It was extremely hard.”

Chelsea Mills

There were difficult discussions between paramedics, Blackley staff and Bryan’s family about what to do for the best.

Bryan was dying and being in hospital would not save him. It was agreed he should remain in the home surrounded by people he knew.

His daughter Susan had asked the carers to give him a message.

“Just tell him there’s Covid outside. We’ve got to be isolated in our own homes. That’s why we can’t come. And just tell him that we love him.”

On the night shift, experienced nurse Herbert Mumbamarwo gave Bryan prescribed painkilling drugs - including morphine - but they weren’t working.

Herbert Mumbamarwo

“Bryan over the last 10 to 12 months has never spoken a complete sentence,” says Herbert. “But that night, he managed to say ‘I can’t breathe, I’m drowning,’ words I didn’t know he could speak. That explains the extent of the trauma he was experiencing.”

In a hospital, Herbert could have turned to senior doctors for advice to make Bryan more comfortable in his final hours, but in the care home he was the only medically-trained person on duty.

“I was going on YouTube, on NICE guidelines, trying to find better ways to help. It didn’t help much. After my shift, I had a feeling of… I’ve failed Bryan.”

Bryan was more comfortable by morning, but died the following night.

Family photo: Susan, Bryan and his wife Sheila

“I feel as though I’ve let my dad down,” says daughter Susan. “Not being able to hold his hand was just horrendous. He relied on me, he used to say he always wanted me there if he was poorly.”

NHS England says care homes had medical support through the pandemic.

Herbert understands the whole system was under pressure, but believes there are still lessons to learn.

“We would benefit from a team of specialists, specifically on standby to respond to extreme cases of Covid. They could give advice on what best to do.

“We’re not defying death, but what we’re trying to do is our mission statement - to make it comfortable.”

In the week Bryan died, care home deaths peaked.

More than 3,300 residents died in England and Wales. At its worst, 540 died in a single day.

It’s a situation that angers Mark Adams from Community Integrated Care - the charity that runs EachStep Blackley.

“Nobody really thought about the challenge that care organisations were going to face until, if I’m being brutal, the body count became so high they couldn’t ignore it.”

On 15 April, as care home deaths reached their peak, Matt Hancock set out his Social Care Action Plan. “Our goal throughout has been to protect residents and to support our 1.5 million colleagues who work in social care,” said the health and social care secretary at the daily briefing. “First and foremost, from the start, we’ve focused on the need to control the spread of infection in social care settings.”

All patients discharged from hospital would now be tested for coronavirus before they left.

- 15 Apr - Social Care Action Plan announced by Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock

- 15 Apr - By now, since 17 March, about 25,000 people in England had been discharged from hospitals to care homes, many without being tested (National Audit Office)

- 17 Apr - “You can wear the same face mask between residents whether or not they have symptoms of Covid-19” - Public Health England advice

- 17 Apr - Day with the largest number (540) of covid-related care home deaths in England and Wales

Previous advice had stated that: “Negative [coronavirus] tests are not required prior to transfers/admissions into the care home.”

There would also be testing for all care home residents and staff showing symptoms. A shortage of tests had seen NHS staff prioritised and few care workers checked.

By the end of April, there was increasing evidence that one of the ways the virus was getting into homes was through staff - particularly those working in more than one care home or hospital. It was also becoming clearer many residents and staff who tested positive for the virus showed no symptoms.

On 15 April, as care home deaths reached their peak, Matt Hancock set out his Social Care Action Plan. “Our goal throughout has been to protect residents and to support our 1.5 million colleagues who work in social care,” said the health and social care secretary at the daily briefing. “First and foremost, from the start, we’ve focused on the need to control the spread of infection in social care settings.”

All patients discharged from hospital would now be tested for coronavirus before they left.

- 15 Apr - Social Care Action Plan announced by Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock

- 15 Apr - By now, since 17 March, about 25,000 people in England had been discharged from hospitals to care homes, many without being tested (National Audit Office)

- 17 Apr - “You can wear the same face mask between residents whether or not they have symptoms of Covid-19” - Public Health England advice

- 17 Apr - Day with the largest number (540) of covid-related care home deaths in England and Wales

Previous advice had stated that: “Negative [coronavirus] tests are not required prior to transfers/admissions into the care home.”

There would also be testing for all care home residents and staff showing symptoms. A shortage of tests had seen NHS staff prioritised and few care workers checked.

By the end of April, there was increasing evidence that one of the ways the virus was getting into homes was through staff - particularly those working in more than one care home or hospital. It was also becoming clearer many residents and staff who tested positive for the virus showed no symptoms.

Other parts of the UK:

- The care home pandemic peaks in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland came after the hospital peaks - similar to England

- In Scotland and Wales, the number of deaths in hospitals rose to 1.4 times higher than average

- At one point, care home deaths in Scotland were 2.8 times higher than usual - in Wales they were three times higher

- Comparable figures for Northern Ireland are not available

(Sources: ONS, NRS, NISRA)

By early May, in Kent, Pelham House was still free of the virus. “We were meticulous about PPE,” says Karen White, one of the home’s most experienced carers. “Temperature-taking every morning, the staff, the residents. We were bobbing along. We were so pleased with ourselves, because we hadn’t got one single case.”

But that was about to change. Francis, a resident for six years, was starting to feel poorly.

“He was a fit and well man at the age of 96, and had served in the war,” says owner Roger Waluube. “He wasn’t feeling well, unusual for Francis, so he went into hospital.”

Francis Chapman (photo: Paul Smith)

The next morning, they got a call saying Francis needed to be discharged. The hospital said there was no clinical need for him to stay. It had followed guidance and tested him, but the results were not back.

The government’s Social Care Action Plan stated: “Where a test result is still awaited, the patient will be discharged and pending the result, isolated in the same way as a Covid-positive patient will be.”

But staff at Pelham wanted to wait until they knew what they were dealing with.

“It escalated to the consultant in A&E being on the phone and really, really requesting and stating that Francis had to come home on that day,” says Roger.

Asked if they felt bullied, he says: “We did. Yes. There was no other option but to take Francis back to the care home and if we didn’t agree, he would be sent back anyway in an ambulance.”

- 22 Apr - “I'm sure we will see a high mortality rate in care homes sadly because this is a very vulnerable group and people are coming in and out of care homes and that cannot, to some extent, be prevented” - Prof Chris Whitty, England’s Chief Medical Officer

- 28 Apr - All social care workers and residents in England eligible for tests, even with no symptoms, but daily care home tests capped at 30,000

- 6 May - “There is an epidemic going on in care homes, which is something I bitterly regret… In the last few days, there has been a palpable improvement” - Boris Johnson at PMQs

Pelham House does not have nursing facilities and Francis was very ill. He was back at the home when staff got the call saying he’d tested positive for Covid-19.

“You knew you couldn’t stop it, you were powerless,” says Roger. “It was very scary. It was inevitable, we knew people were going to go.”

The Kent and Medway Clinical Commissioning Group said in a statement: “As symptoms can take up to 14 days to appear following exposure, it is likely the resident would already have been infected.”

It also said the home was given advice and support around minimising the risk of Covid-19 spreading in the home.

In his final hours, Francis was moved to a nearby hospice, which provided him with the end of life care he needed.

Other Pelham House residents were now also falling ill with the virus.

Blackley’s battle

At Blackley, Covid-19 had spread from one end of the building to the other. Staff were worried about 91-year-old Vera, normally seen making her way around the home with her walking frame.

“She does look after everybody, mother everybody. And she chats non-stop, so that’s what we like,” says advanced carer, Debra Fielding.

But Vera had developed a cough and her temperature was up.

Vera

Another resident, Michael, was taken to hospital because of his particular underlying medical condition. His daughter, Michelle Phillips, is Blackley’s manager.

“He was poorly when he left. When he spotted me in reception, he waved and shouted after me that he loved me. That just made me cry.”

At this point, Blackley was only able to test residents or staff with Covid-19 symptoms. To stand a chance of controlling the virus they needed to be able to identify all those who were infected but without symptoms.

Phil Benson was on the phone every few days trying to get more tests.

“I remember begging ‘Please can one of these people come and just test? Can we not have everyone tested? Surely there’s such a severe outbreak here, it’s in everyone’s interest to be tested?’

“And it was ‘No, the policy is clear. We only test people who’ve got symptoms.’”

- 13 May - “A huge exercise in testing is going on - a further £600 million, I can announce today, for infection control in care homes… There is much more to do, but we are making progress” - Boris Johnson at PMQs

- 15 May - “Right from the start we've tried to throw a protective ring around our care homes” - Health and Social Care Secretary, Matt Hancock

- 17 May - “Yes our guidance has altered over time, but that is a result of our scientific understanding of the virus changing over time” - Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove

Nearly two months after the country locked down, on 15 May, the Health and Social Care Secretary, Matt Hancock, announced an infection control plan for care homes.

It included £600-million ring-fenced to help with increased Covid-19 costs, a named clinician to provide each home with medical support and testing for all care home residents and staff.

At the daily briefing, the health secretary said that: “From the start we’ve worked incredibly hard to throw that protective ring around our care homes.”

“What protective ring?” asks Pelham House manager Roger Waluube. “We don’t understand what the protective ring could have been or was.”

‘It was horrific’

Everyone in Pelham House could now be tested. All 20 residents and 17 staff were checked. Two days later the test results came back. “The manager was just sat there with his mouth open,” says carer Karen White.

“He just pointed at the screen and it was horrific. Every resident apart from two were positive. And 80% of the staff.”

Karen White

It meant most of the staff had to leave immediately.

“They had to down tools,” remembers Roger. “That left us in a very vulnerable position, particularly when the cook has to suddenly stop her cooking and go home.

“There’s three or four of us who’ve been on the frontline as such and continually testing negative. We could keep going.”

Overall, 19 Pelham House residents tested positive and nearly half those living at the home died.

The home normally averages about three deaths a year, but it had nine in just 10 days.

“We’re not used to death at this scale. Having to say goodbye to so many people so quickly,” says Roger.

Carer Karen was hit hard after the funeral of Peter Baker, a resident with learning difficulties and no family, soon to celebrate his 76th birthday.

“He just gently passed away,” she recalls tearfully. “He trusted us to look after him. And he always kept saying ‘Love you girls, I love you girls, I’m so happy here.’ We just let him die. With his learning difficulties he wouldn’t have understood.”

Pelham House was also facing another big problem. By July, it was virus free, but the deaths of half of its residents meant the home had lost 50% of its income. Pelham was rated “good” by the regulator, the Care Quality Commission. Before Covid-19, Roger Waluube had plans to develop and redecorate.

Coronavirus changed all that. “We were a very healthy and viable business,” he says. “Now our future is in the balance and the outlook is not good.”

Roger Waluube

By late June, he estimated they had enough money to last six to eight weeks. With little prospect of new residents moving in, he turned to Kent County Council for help.

Since March, the government has given councils £3.7bn to help with the additional pandemic costs. The money is for all services under pressure - including support for children, the homeless and transport services.

The Local Government Association, which represents local councils, estimates about 40% of the first £3.2bn received has gone to adult social care, including care homes.

So far, Pelham has received about £40,000 in council help. Roger is discussing loans, but he estimates it’ll take at least another £100,000 for the home to survive.

Closure would see residents like Doreen having to find a new home. It would be difficult for them all.

Residents grow to see this place as their home, says Roger. “Moving people from one care home to another never generally has great results because that adjustment can take its toll on people.”

At Blackley, there was finally some good news. Staff lined up in reception to welcome Michael back. He was in hospital with the virus for two weeks but recovered. As the ambulance crew wheeled him in, his daughter and home manager, Michelle, gave him a big hug.

Michelle Phillips

“I’m really happy,” she laughs. “A feeling I’ve not had for a while.”

Vera also recovered and was able to celebrate her 92nd birthday. In mid-June, she saw her daughter and grandson at a distance. She sat on one of the home’s balconies while they were in the garden.

Vera smiles at her daughter and grandson

Over six weeks, 16 of the home’s 55 residents had Covid-19 officially - while others had symptoms. Nine died.

With the outbreak under control, Phil Benson finished his work at Blackley and went on to help other homes.

By early July, Pelham House was also coronavirus-free, but its future remained uncertain. Roger Waluube is crowdfunding to see if he can save the home, but he faces some hard decisions.

“I will not get to the point where I’ve got two hours to go, and I’ve run out of cash or I can’t care for people any more,” he says.

Pelham House was also facing another big problem. By July, it was virus free, but the deaths of half of its residents meant the home had lost 50% of its income. Pelham was rated “good” by the regulator, the Care Quality Commission.

Before Covid-19, Roger Waluube had plans to develop and redecorate. Coronavirus changed all that.

“We were a very healthy and viable business,” he says. “Now our future is in the balance and the outlook is not good.”

By late June, he estimated they had enough money to last six to eight weeks. With little prospect of new residents moving in, he turned to Kent County Council for help.

Roger Waluube

Since March, the government has given councils £3.7bn to help with the additional pandemic costs. The money is for all services under pressure - including support for children, the homeless and transport services.

The Local Government Association, which represents local councils, estimates about 40% of the first £3.2bn received has gone to adult social care, including care homes.

So far, Pelham has received about £40,000 in council help. Roger is discussing loans, but he estimates it’ll take at least another £100,000 for the home to survive.

Closure would see residents like Doreen having to find a new home. It would be difficult for them all.

Residents grow to see this place as their home, says Roger. “Moving people from one care home to another never generally has great results because that adjustment can take its toll on people.”

At Blackley, there was finally some good news. Staff lined up in reception to welcome Michael back. He was in hospital with the virus for two weeks but recovered. As the ambulance crew wheeled him in, his daughter and home manager, Michelle, gave him a big hug.

“I’m really happy,” she laughs. “A feeling I’ve not had for a while.”

Vera smiles at her daughter and grandson

Vera also recovered and was able to celebrate her 92nd birthday. In mid-June, she saw her daughter and grandson at a distance. She sat on one of the home’s balconies while they were in the garden.

Over six weeks, 16 of the home’s 55 residents had Covid-19 officially - while others had symptoms. Nine died.

With the outbreak under control, Phil Benson finished his work at Blackley and went on to help other homes.

By early July, Pelham House was also coronavirus-free, but its future remained uncertain. Roger Waluube is crowdfunding to see if he can save the home, but he faces some hard decisions.

“I will not get to the point where I’ve got two hours to go, and I’ve run out of cash or I can’t care for people any more,” he says.

The government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic in the social care sector was “slow, inconsistent and at times negligent” is the damning verdict of MPs on the Public Accounts Committee in their report of 29 July.

The decision to allow hospital patients in England to be discharged to care homes without tests at the start of the pandemic was “reckless”, they say.

The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care declined to be interviewed by Panorama. In a statement, his department said:“We first published guidance for the social care sector in February and have since announced a raft of measures. Our help has meant almost 60% of England’s care homes have had no outbreak at all.”

The government has also promised to bring forward plans for reforming the care system in the near future. It has started cross-party talks on what it describes as a complex issue.

Mark Adams, of Community Integrated Care, says that change has to happen soon.

“When we look back, we will see this as one of the most mismanaged national challenges we’ve ever faced,” he says.

“You can’t have a disconnected health and social care system. It can’t be left to local authorities, whose budgets are being cut, and [who] then have to think about who gets care and who doesn’t.”

No government will get everything right in the extreme situation a pandemic presents, but it will be judged on how it protects the most vulnerable.

Ellen

In the kitchen at Blackley one resident with dementia, 88-year-old Ellen, stands and sings.

Her voice stitches together memories from a past that is slipping out of her reach.

But the question she asks is one for all of us.

“If I give my heart to you, will you handle it with care?”

How do other care home managers feel?

“Unbelievable how hospital staff sacrificed integrity and well-being of patients to comply with government guidelines”

“We were pressurised into taking Covid patients”

“We were made to feel guilty for not taking untested residents from hospital as it was 'our duty' to assist the NHS”

“Abundantly clear the government had no real understanding of the care sector, which was shameful”

“No GPs have set foot in our home since March”

“It was chaos - one GP was very supportive and visited, others did not”

“Social care sectors have played second fiddle to hospitals”

“Local community support has been amazing”

“Very easy to point fingers at government when care companies themselves were possibly too slow to react”

“Government had no real understanding of the care sector - shameful”

“Worst experience of my life but I dare not speak out because we will be targeted by the local authority”

“Fantastic support from NHS Rapid Response Team”

“Protecting the NHS was at the forefront, social care was collateral damage - a national disgrace”

“We felt abandoned”

“Social care is still very much on the front line, and is still coming second”

Taken from questionnaire responses from 124 Care England or National Care Association members, managing over 350 care homes. Responses received by Panorama 26 June-14 July.

How do other care home managers feel?

“Unbelievable how hospital staff sacrificed integrity and well-being of patients to comply with government guidelines”

“We were pressurised into taking Covid patients”

“We were made to feel guilty for not taking untested residents from hospital as it was 'our duty' to assist the NHS”

“Abundantly clear the government had no real understanding of the care sector, which was shameful”

“No GPs have set foot in our home since March”

“It was chaos - one GP was very supportive and visited, others did not”

“Social care sectors have played second fiddle to hospitals”

“Local community support has been amazing”

“Very easy to point fingers at government when care companies themselves were possibly too slow to react”

“Government had no real understanding of the care sector - shameful”

“Worst experience of my life but I dare not speak out because we will be targeted by the local authority”

“Fantastic support from NHS Rapid Response Team”

“Protecting the NHS was at the forefront, social care was collateral damage - a national disgrace”

“We felt abandoned”

“Social care is still very much on the front line, and is still coming second”

Taken from questionnaire responses from 124 Care England or National Care Association members, managing over 350 care homes. Responses received by Panorama 26 June-14 July.

Written by Alison Holt

Editor: Paul Kerley

Illustrations/graphics: Sana Jasemi

Photos: Tom Jenner, Craig Chambers, Paul Smith, EachStep Blackley families

Research: Alison Benjamin, Ben Butcher, Helen Clifton, Abi Evans, Eleanor Plowden, Janine Weaver