A hair’s breadth

Election battleground: Southampton

As politicians campaign for votes, we are looking closely at the places where the election could be won or lost. One of Southampton’s three constituencies was balanced on a knife-edge in 2017 - if people who rarely vote came out in force, the result could change.

By Jon Kelly

Tammy Cosens was four years old when she first started playing with other people’s hair. Her mum’s friends would come round to their flat and let Tammy style them. She adored it. When she learned she could make a living as a hairdresser, she set her heart on it as a career.

Back then she lived on the third floor of a four-storey walk-up block in Holyrood, a post-war council estate near the centre of Southampton. It was a lively multicultural area, with many Indian, Pakistani and Jamaican families, and Tammy loved it there.

This was the early 1980s and there wasn’t much traffic, so she’d play on the streets with the other children and walk each day to school. One of her neighbours was Craig David, the future UK garage star. Their families were friendly.

Then, when she was 13, Tammy’s mum moved the family to another estate in Swaythling, in the north of the city. They lived in a house now rather than a flat but Tammy didn’t like the area so much.

In Holyrood there had been plenty of children her own age to make friends with, but now most of the kids were a few years older. For the first time Tammy, who is mixed-race, experienced racist abuse. Her mum didn’t like her hanging around in the street any more.

Tammy only went to school to socialise. She was intelligent, but the teachers didn’t know how to deal with her dyslexia. “They would just class you as thick,” says Tammy, now 44. She’d play the class clown, but this was borne of insecurity. “I don’t think I was a very confident kid,” she says. “I was more of a follower than a leader.”

Then it was time for all the pupils in her year to go out and do work experience, and Tammy thought she’d hit the jackpot - she was offered an interview for a job at a hairdresser’s salon. It was the opportunity she’d always dreamed of. “I really wanted to do it,” she says. “I really tried.” She did her best to be respectful and took care answering all the questions she was asked. But the owner reported back that Tammy had a “bad attitude”.

Tammy didn’t understand why the owner would think this. “Could be a racist thing,” she says. When she returned to her classes, the teacher who’d been given the report from the salon owner slammed a door in her face. After that, Tammy never went back to school.

Southampton is a city of sharp contrasts. There are the marinas like Ocean Village and Shamrock Quay, with their yachts and luxury flats; then there are the sprawling council estates like Thornhill, Weston and Townhill Park.

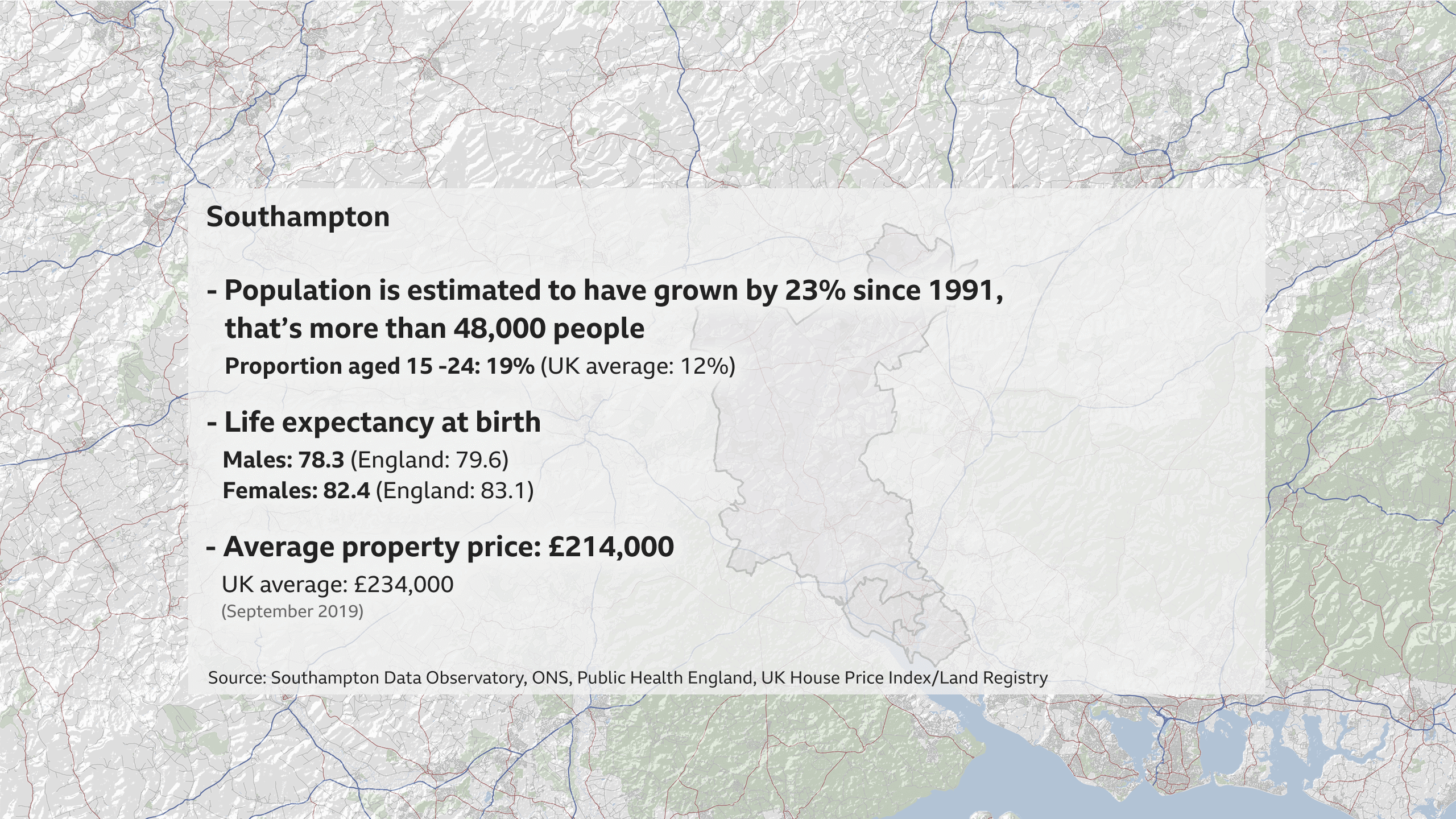

Its economy is a mixture of the traditional and the ultra-modern. While some other cities have seen their docks go into terminal decline, the port of Southampton is still a major employer, supporting an estimated 45,000 jobs. At the same time, high-tech jobs are on the rise and there’s a student population of 40,000 -19% of the population is aged 15-24, compared with a UK average of 12%.

All these factors makes for closely fought electoral territory. Control of Southampton council changed hands six times between 1997 and 2012, and the Westminster seats reflect the varied communities that make up the city.

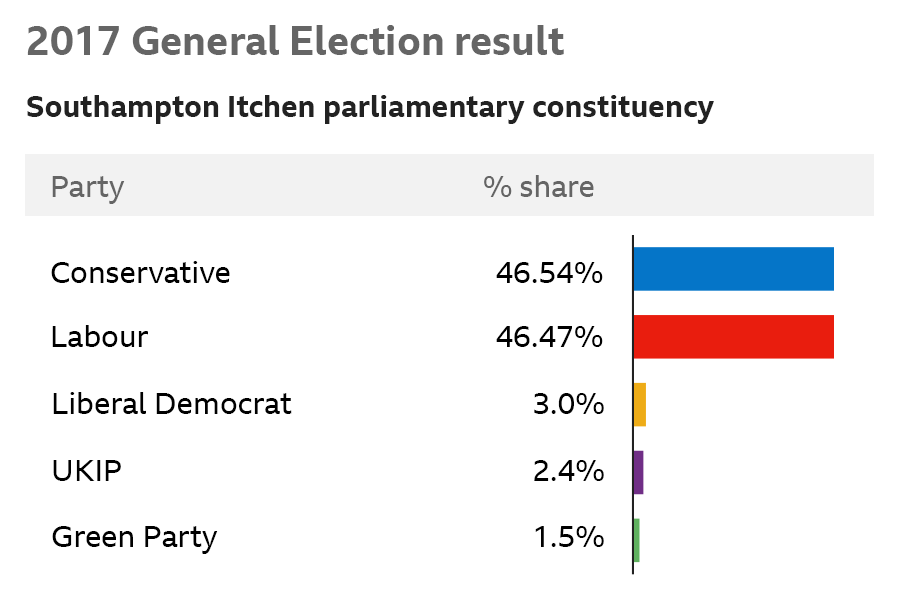

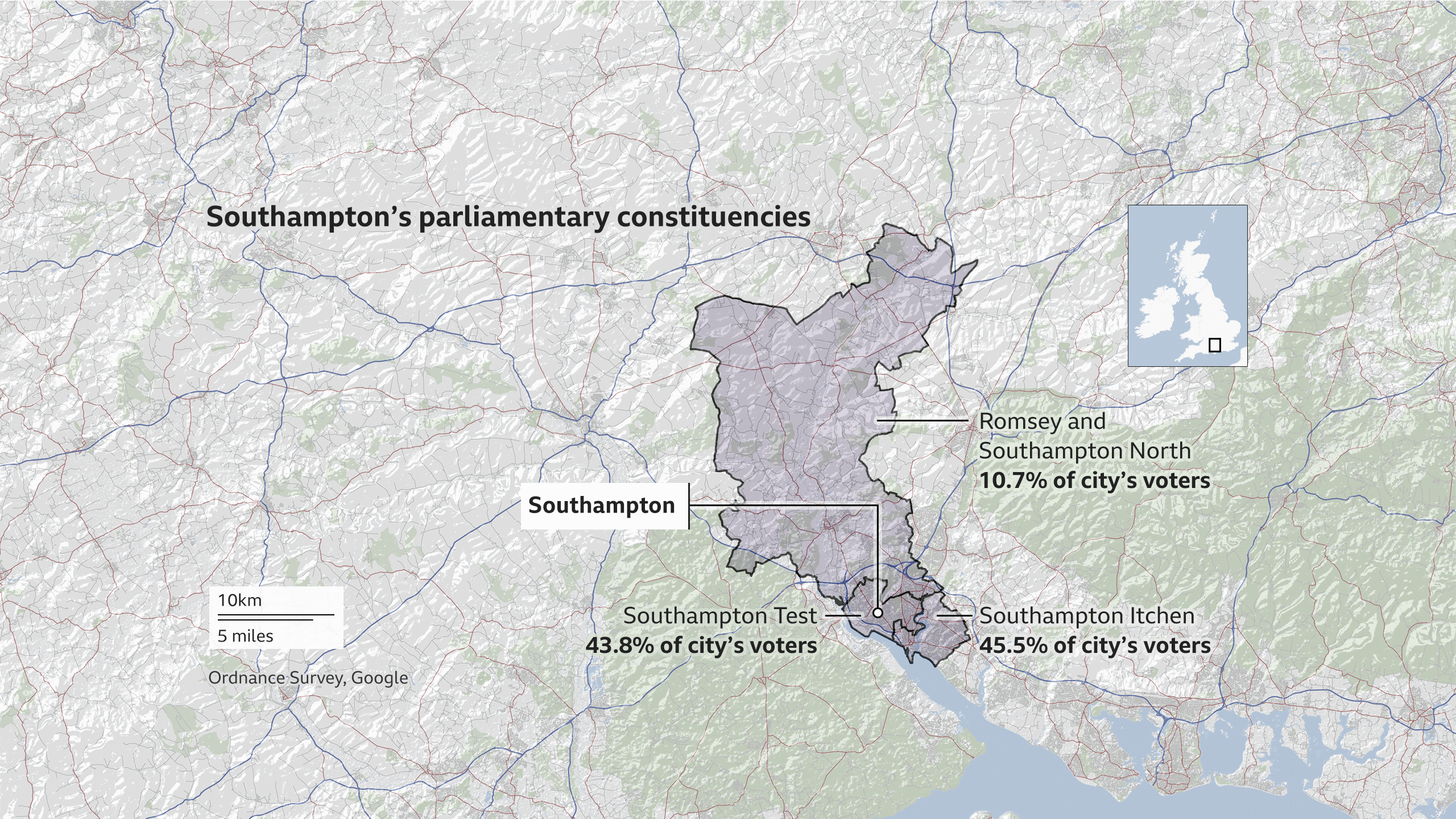

To the east is Southampton Itchen, which the Conservatives snatched from Labour in 2015 and then held in 2017 by a margin of just 31 votes.

To the west is Southampton Test - slightly wealthier, a little more diverse and home to the University of Southampton, it was once considered a bellwether but has been held by Labour since 1997.

There’s also Romsey and Southampton North, represented by the Tories since its creation in 2010, where the Liberal Democrats are the principal challengers.

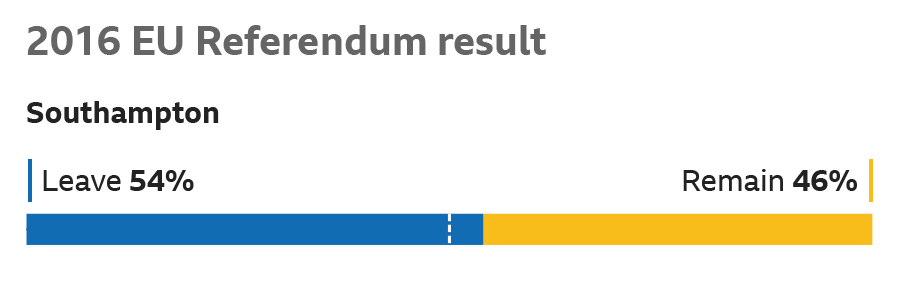

In 2016, Southampton voted for Brexit by 53.8% to 46.2%, slightly above the UK average.

And like the country as a whole it was divided along demographic lines, with the more cosmopolitan Test constituency choosing Remain, while in Itchen, with its higher proportion of white working-class voters, Leave came out on top.

Liam Doe looks elated. A serial entrepreneur, it’s only been a week since he launched his latest business venture, a luxury shared workspace called The Old Bond Store, right in the centre of Southampton.

Built in a refurbished warehouse, it has business lounges, an events floor and tastefully furnished work space over three storeys.

Liam is pitching it at the higher end of the market - he’s aiming to sign up 100 business leaders at a rate of £300 a month, on the basis that it’s a more congenial spot for them to get things done than coffee shops or their kitchen tables.

His judgement is that Southampton has enough high-end clients to justify his investment - quite a vote of confidence in the city, the kind you’d expect from a proud native son. But Liam, 39, wasn’t born or raised there.

In fact, he grew up 15 miles away in neighbouring Portsmouth, on the sprawling Paulsgrove estate. It was a close-knit place where generations of the same families lived - Liam’s dad, who had a small construction company, and his mum, a nurse, had been brought up there too. When Liam, a Portsmouth fan, was signed by Southampton FC’s youth team, he learned all about the sporting rivalry between the two cities.

He was the first in his family to go to university, and then had a few years working for other people - a recruitment firm, a franchising company and so on. But he knew that eventually he wanted to be his own boss.

Then one day Liam’s dad called to say he was thinking of retiring. Liam knew nothing about construction, but he when he looked at his dad’s books he could see it was a good business. With a bank loan, he bought a stake and, alongside a business parter, set about building up the firm. They were hugely successful at first. “At 27 years old I was running a £5m-turnover business and thinking I was bulletproof,” Liam says.

He wasn’t. The recession hit and, eight years ago, the business failed. “We lost everything,” says Liam, now 39. “Which was tough. It wasn’t good for either of us or our families. But we learned from it.”

The construction firm was re-purposed as a recruitment agency, finding work for its old employees. Liam and his partner set up an accountancy firm serving self-employed contractors - by the time he sold it this year it had 800 clients. He began investing in property, too. When the Old Bond Store came on the market, Liam saw an opportunity.

Liam believes that while his home city of Portsmouth aspires to be, like Brighton, a place you go to have fun, Southampton sees itself as a regional hub in the mould of Bristol or Birmingham - the capital of the south coast.

“There is real ambition here,” he says. “It’s a thriving business community.” He sees commuters standing on the platform at Southampton Airport Parkway station at 5am each day and believes they and their employers will see the benefits of remote working.

He stresses he isn’t very political. He’s voted maybe twice in his life. But there’s one thing about politics that annoys him - the way MPs talk about businessmen needing stability to make decisions.

“You’re never going to get stability,” he says. That’s the most important thing he learned from building up a business, losing it and building it up again. “It doesn’t exist.”

Tammy sat in her chair at a salon. She was there as a client but she’d been studying for a hairdressing qualification. She made sure to let the owner know this. Could she come in and do work experience?

The past few years had been hard for Tammy. She’d worked for a while in a chicken factory until, at 18, she gave birth to her son. It was tough bringing him up on her own.

Now, at the age of 25, she was relatively old for a hairdressing trainee. But she turned that to her advantage. “Because I was older I could see more, clean up more, be on the ball,” she says. “I was eager to ask questions, see what they were doing.” Four weeks after she started, she was offered a permanent job.

At the time, the salon that took her on was the only one in Southampton specialising in afro-textured hair. Previously, many black people who lived in the city had felt obliged to travel to London.

Like other UK cities, Southampton has become increasingly multicultural. In the 2011 census 14.2% of the population were recorded as black and minority ethnic (BAME) and 22.4% were non-white British.

Ali Beg set up Awaaz Community Radio - a local station that broadcasts in nine languages - because he felt the growing Asian community wasn’t being catered for. “I believe that integration is better than isolation,” he says. “Growing up in the 70s and 80s, you used to listen to English music as much as ethnic music. Why not have a platform where we have both out there?”

Tammy had a similar philosophy. She cut hair for black people and white people alike. After two years in the salon, she’d built up enough of a clientele to set up on her own. At first she’d cut clients’ hair in her flat in Bitterne, in the east of the city. She removed a built-in wardrobe and fitted a mirror, lights and sockets. Later, she worked in a barber’s shop.

By 2011 she’d saved up enough to take out a lease on a salon of her own. It was next to Ocean Village, a marina at the mouth of the River Itchen.

There were four chairs, so she could rent three to other hairdressers. Tammy’s dream had come true at last. She’d recently given birth to her eldest daughter and this was a chance to give her the life she deserved.

It was hard work, though. After her second daughter, now seven, was born, Tammy had post-natal depression, but she only took two months' maternity leave. “When you’re depressed you have days where you don’t want to get dressed - but I had to open up the shop,” she says. “I couldn’t not open up the shop.”

She stuck at it for eight years. This July, however, she had to let it go. Her children wanted to be at home, not with a childminder.

It made sense to rent a chair in someone else’s salon instead and work around school hours. She was sorry that her dream didn’t last forever, but as a working single mother, this change has been better for her mental health.

“My anxiety has gone down loads,” she says.

Battlegrounds

There are issues that matter to Tammy, issues that Westminster has influence over.

As well as wanting more support for small business, she’s concerned about the lack of affordable homes in Southampton. “They’re building more student accommodation, more private accommodation - there’s no social housing.” She can’t afford to buy her own flat.

But on 12 December, she isn’t planning to vote for anyone.

So far, it seems to her these issues aren’t at the forefront of the election campaign. “Isn’t it just who’s running to see who’ll sort the Brexit deal out?” she asks. Like Liam, she’s voted a couple of times in her life - and the 2016 referendum on EU membership wasn't one of them.

“I didn’t know anything about it, and I probably would have been choosing for the wrong reasons,” she says. Back then, she understood why many in Southampton had concerns about immigration. “What annoys me is that you can’t get a doctor’s appointment. School places are so strict now because they’re over-subscribed. But that’s not [the immigrants’] fault, at the end of the day - it’s the government’s fault.”

Over time, she’s become more sceptical about the supposed benefits of Brexit.

At the salon where she now works there are hard-working Eastern European hairdressers who are fearful for their futures. “What they [the government] are actually doing is pointless,” she says. “It’s going to take longer at borders - what’s that going to achieve? I don’t feel that’s going to solve anything.”

Liam didn’t vote in the EU referendum either. Like Tammy, he didn’t feel qualified enough to make a call. But unlike her, he’s shifted towards thinking the government needs to get Brexit over and done with.

“I think it just needs to happen,” he says. “My business head says to me commerce has to happen, as it's happened for hundreds of years. BMW in Germany are going to need to sell the UK market cars. I’ll be glad to see it done.”

Brexit supporters in Southampton have made much of the fact that most exports that pass through the city’s port are destined for non-EU countries.

“None of our clients have said to me, ‘We are waiting to hear what’s happening with Brexit.’ We’ve all got a bit used to it, and are just getting on with it,” says Gill Gould, 69, who runs a marketing communications company, Carswell Gould.

Local companies are more concerned about finding the highly trained staff they need to compete in the high-tech marketplace, she says. “What we really need is people coming out of schools, colleges and universities who are ready with the skills that businesses require.”

But others - not least the thousands of EU citizens who have come to Southampton to work and study - may be less relaxed about the situation. The council estimates that there are 8,391 Polish workers in the city. The universities, too, rely heavily on EU funding.

In the end, non-voters - or at least irregular voters, like Tammy and Liam - might prove to be decisive, if this time they decide to exercise their right to cast a ballot.

In 2017, there were 24,675 eligible voters in ultra-marginal Southampton Itchen who either didn't vote or spoiled their ballot paper. The winner, Conservative Royston Smith, won 21,773 to Labour’s 21,742.

Had the non-votes counted as “none of the above”, then "none of the above" would have won the seat handily - a statistic that makes Tammy and Liam, for all their differences, representative of a bloc that could upset Southampton’s political equilibrium.

For a full list of general election 2019 candidates standing in Southampton see our pages below:

Romsey and Southampton North parliamentary constituency