Crazy Golf just got (a bit) serious

The family-favourite seaside pastime has dreams of Olympic representation, players bordering on obsessive, and supports hundreds of jobs in multi-million pound businesses. No wonder they call it “serious fun”.

Amid the towering pines of the Augusta National Golf Club in Georgia, Tiger Woods slips on the Masters Green Jacket to mark one of the most astonishing sporting victories of the decade.

The new US Masters champion also receives a sparkling trophy and a winner’s cheque for just over $2m (£1.6m).

A few days earlier, thousands of miles away in the UK, amid the rumble of traffic on the A20 Sidcup bypass, Mark Wood was also presented with a jacket as a Masters champion golfer.

This one - a tweed blazer - was bought from a charity shop in Southend, Essex.

Messrs Woods and Wood are similar in name but orbit different golfing planets.

Just competing with a Bridgestone golf ball pays Tiger Woods a seven-figure sum from the manufacturer.

In Mark Wood’s sport, players are known to keep their ball in a sock tucked in their trousers, to maintain its even temperature so it rolls at a consistent speed.

And, for the Hackney Council finance manager, winning minigolf’s British Masters at Mr Mulligan’s Dino Adventure Golf has netted him just £50 in prize money.

“The prize isn’t fantastic, but it is more the camaraderie and being competitive,” says Mark.

“It does cost me with my wife though. She hates sport.”

Following the Sidcup tournament, the British Minigolf Association caravan moves on. The next competition is in Norfolk, then Solihull.

All roads on this player pilgrimage lead to Hastings in East Sussex, for the weekend of 8 and 9 June, and the big one – the World Crazy Golf Championships.

Anyone can enter, and the victor will take home £1,000.

An archer’s exact strike helped the Norman conquerors to victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Will, Martin, Marion and David are among the players aiming for similar, if less deadly, accuracy at the so-called World Crazies.

Just days before the competition, the quartet agreed to share some of the secrets of top-level crazy golf with me.

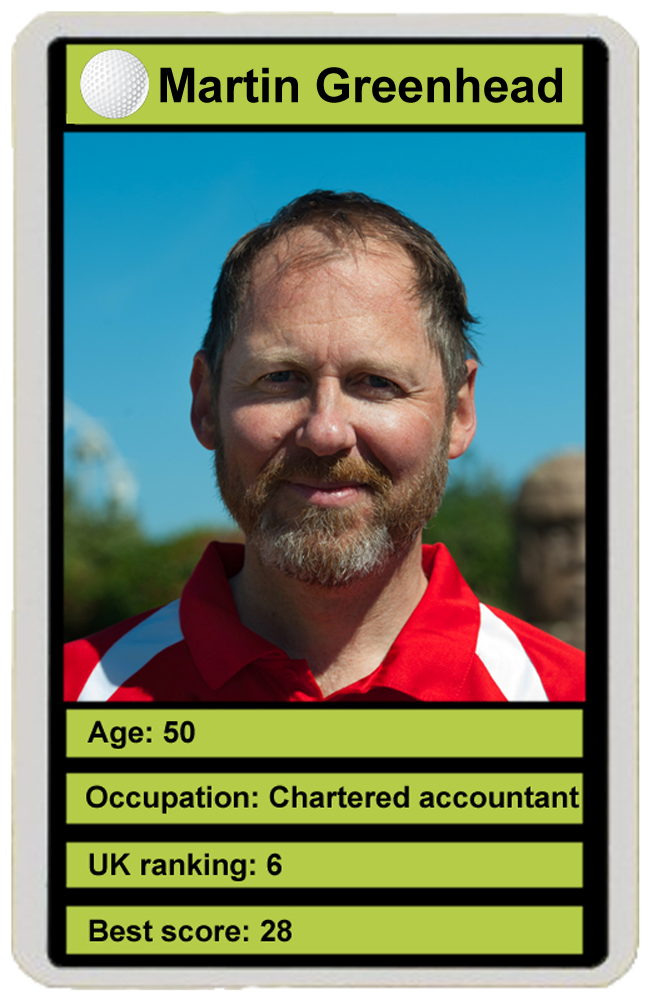

Martin became hooked on the sport after playing as an alternative to a cancelled cricket match in 2012. Representing his country in the sport has taken the 50-year-old across Europe.

Preparation is key, he says. He is an accountant so, appropriately, he carries a golfing ledger.

He has a little red notebook for each course he plays. In it he makes notes, and marks where to aim his ball from different points on each hole. Many of the top players have similar guides.

This forethought extends to deciding what is best to wear.

“The most important thing is comfortable shoes. It is amazing how many miles you can clock up,” says Martin, also dressed in his GB T-shirt.

“Then you need protection from the sun and, as it is England, we all have a full set of waterproofs.”

Europe’s best players often have a coach to carry an umbrella over them, not to shelter them from rain, but to stop their ball heating up too much in the sun, and to avoid distracting shadows.

There is something else vital for women who want to win.

“I’ve got a new golfing bra,” says Marion, a 67-year-old who plays every week in retirement.

“Otherwise it is distracting if the straps fall down.”

Will shows off his specialist putter. Each player has something similar. It is rubber-headed, and weighted at the bottom. This leads to a smoother, cleaner, strike, he tells me, and allows you to put some spin on the ball.

A specialist putter is the first major investment made by regular players, generally ordered from Sweden or Germany and costing about £80.

The next are balls. Minigolfers don’t use regular golf balls. The ones from the kiosk hardly bounce (a safety feature to protect occasional players from ricocheting shots).

Instead, they use balls shipped over from Europe. A little smaller than regular golf balls, they look more like squash balls, cost £10 to £15 each, and are perfect for bouncing off obstacles into the hole.

“You can get a bit obsessive about them,” says Martin. “I have about 100.”

Uniquely, the World Crazy Golf Championships have a standard-issue ball each year. It is a well-guarded secret. Competitors can only use it for the first time on Friday’s official practice day.

In other competitions, the rules state you can use a different ball on any hole, but you must complete a hole with the same ball that you started with. So, in theory, players can use 18 different balls on an 18-hole course.

Some are heavier, some have more bounce, some just look good.

The choice of which one to use depends on weather conditions, a touch of superstition, and the obstacles that need to be negotiated.

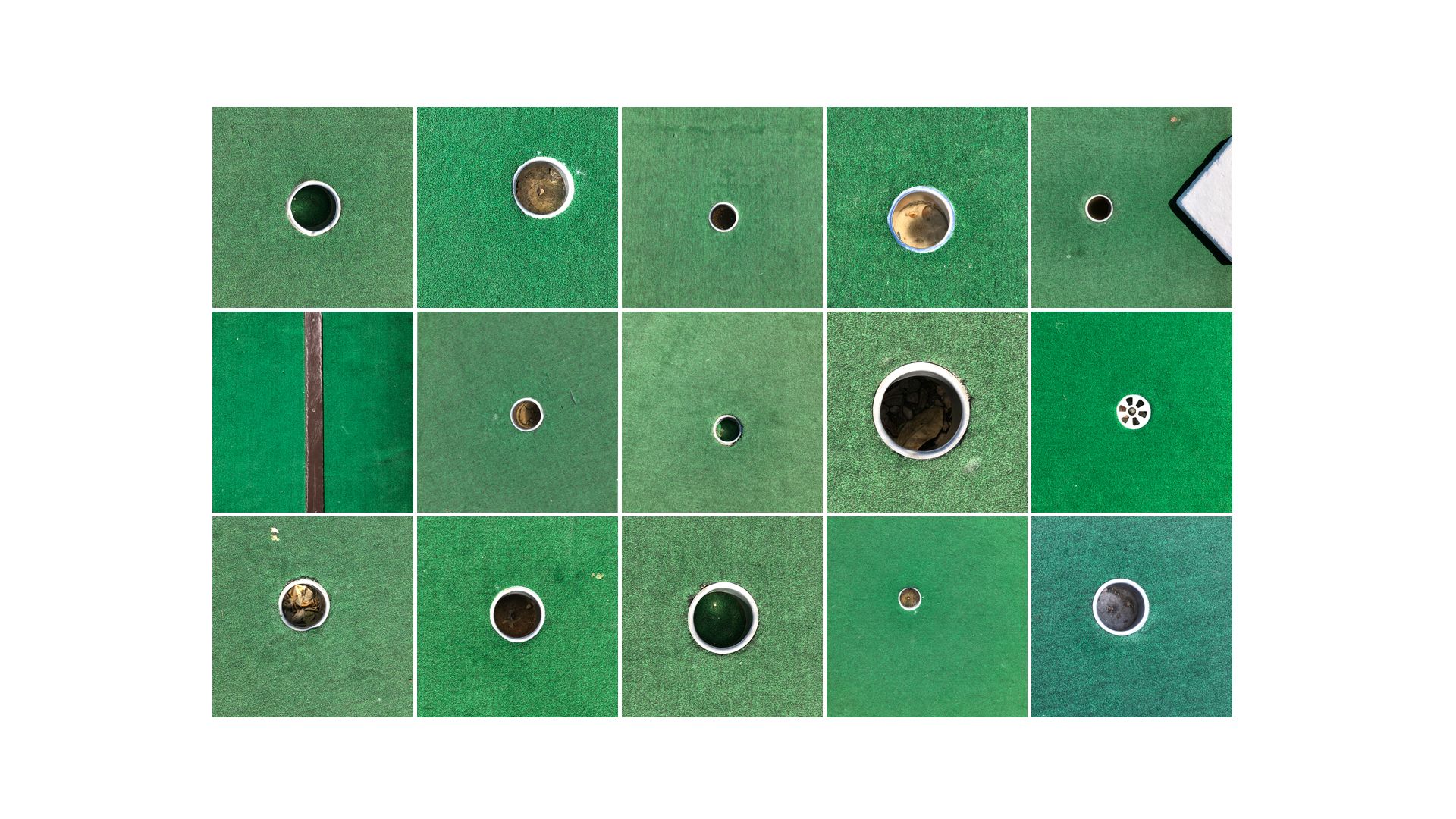

The classic courses – like the Hastings crazy golf course, designed by “big golf” legend Arnold Palmer – have lots of obstacles, from wind and water mills to bridges and cliffs.

In crazy golf, these are found on the playing surface, and players have to putt their ball through or over them. In adventure golf, the features are often next to the holes, with players instead having to negotiate humps, bumps and big slopes. Minigolf is the umbrella term for the sport as a whole.

Stepping up to the first hole, I wonder what kind of score I should be aiming for to compete with the best. The answer is two shots or fewer on each hole – a total score of 36 or fewer. Last year’s World Crazies champion averaged a score of 32 on his seven, 18-hole rounds.

The world regulations state each player starts and completes the hole separately, and in turn. Only on the final round of the World Crazies does everyone play each hole at the same time – known as “crazy, crazy rules”.

I am last to play but the quartet nod in approval as I roll my first shot up close to the hole. My score of two on the first is repeated on the second hole.

I watch as Martin’s ball bounces in and then out of the hole on the third. My kiosk-issue safety ball drops on my first shot, and stays there.

A hole-in-one! Except it is not. It is called an ace in crazy golf.

Will has been telling me where to aim my ball. The 20-year-old student and part-time football referee is not only the highest-ranked player in attendance, but also the Great Britain coach at the next international tournament in Gothenburg.

I ignored his advice, aiming to ricochet off a side wall instead of playing safe and straight.

On the fourth hole, I listen to Will’s guidance and in it goes - again. A second straight ace, and I sit top of the leaderboard.

I raise my arms aloft and yell in delight, only to learn that cheering is “a very touchy subject” in tournament minigolf.

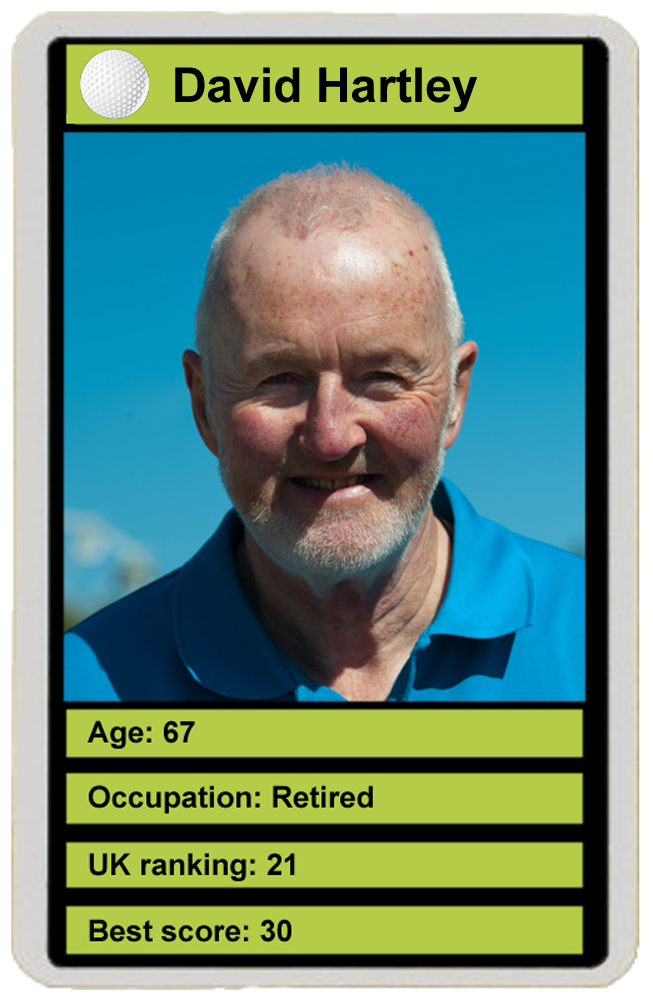

“Some people like to announce to the world if they get an ace. Sometimes very loudly. It is not always approved of,” says David, a pensioner and former manager at the Hastings course.

Off we go to the fifth hole – the most iconic of all, the windmill.

The best players used to avoid its rotating blades by sending their ball around it. A rule change, and a newly-added wooden board, mean they have to go underneath it, with good timing as well as accuracy.

We all send our balls through without embarrassment.

It is the last time my luck holds.

The slide in my score coincides with the actual slide on the seventh hole. The ramp is steeper than expected and my ball rolls back down past my feet.

At the end of hole nine, Will adds up the halfway scores.

“You were on two under [a par score],” he says. “But you are not anymore.”

Total humiliation is avoided thanks to some global rules. The maximum number of shots allowed on each hole is six, after which an automatic score of seven is recorded.

Any ball resting against the side can be moved eight inches onto the playing surface – the length of a scorecard – to allow for some kind of putting backswing.

However, there are some common mistakes among the inexperienced.

Firstly, there are no “gimmes”. Never pick up your ball, even if it is next to the hole.

“Putt with both hands - and bending your knees a bit helps,” says Marion.

“Pace control of the ball is just as important, if not more so, than accuracy,” says David.

So, should we take it seriously?

“It’s Crazy Golf. Of course it’s not serious,” says reigning champion Marc Chapman.

“But it is. I’m a world champion. That’s quite a serious thing for me.”

Only a select few players have ever won the World Crazies. Only one of them – Olivia Prokopova, from the Czech Republic and who started playing the sport at the age of nine - is a woman.

But this is not a male-dominated sport. Far from it. That might just be because it was only women who played when it all began.

It was unbecoming of a lady to swing a club violently in the 1860s, so a minigolf course was created at the home of golf.

The St Andrews Ladies' Putting Club, later known as the Putting Club, in Scotland is thought to be the first minigolf course ever made. It is now commonly known as The Himalayas owing to its tricky peaks and troughs.

It is open to the public (of all sexes) nowadays, but when it was founded in 1867, it was designed as entertainment for the sisters and daughters of the golf club’s members.

The sport of golf has had a well-documented representation issue. Some of the most high-profile courses, hosting the biggest tournaments in the world, have only recently ended men-only membership.

Minigolf has no such problem. Some of the world’s best minigolf players are women, and while some tournaments distinguish between male and female competitions, many do not.

“This is what Emmeline Pankhurst was fighting for all those years ago,” says enthusiast Marion Hartley.

To play minigolf?

“Among other things. It was for the vote, of course, but it was to make women as equal as men. This is a sport where it does not matter,” she says .

The St Andrews Ladies' Golf Club was formed in 1867. PHOTO: Women and children play golf at the historic course in the late 19th Century (Print Collector/Getty Images)

The St Andrews Ladies' Golf Club was formed in 1867. PHOTO: Women and children play golf at the historic course in the late 19th Century (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Forty years after the ladies of St Andrews started playing the game, the emergence of a more recognisable form of crazy golf began.

Gofstacle required coloured golf balls and putters, and players negotiated hoops, rings, a tunnel and a bridge.

“It is played like golf croquet,” the London Illustrated News explained to the curious reader of 1907. "Its popularity is undoubted.”

Then the craze swept America.

It began with a course built at the North Carolina home of the English shipping magnate James Wells Barber, called Thistle Dhu.

It was described as “the world’s craziest, most scientific, and most aggravating golf course” by an article in the Altoona Mirror in 1928.

Soon there were courses everywhere. There were 150 rooftop courses in New York alone. It was a minigolfing golden age.

But then popularity sunk with the economy and it would be decades before the sport was widely played again in the US.

Thistle Dhu Putting Course, Pinehurst Resort Golf Course, North Carolina. PHOTO: Alamy

Thistle Dhu Putting Course, Pinehurst Resort Golf Course, North Carolina. PHOTO: Alamy

So the putter was passed back to Europe. Sweden emerged as a centre of minigolf as courses were set up in public parks.

It took until the 1960s for courses across Europe to look more like the ones we see in the UK today.

Felt became the common playing surface from the 1960s. The reason for that, as any seaside holidaymaker will know, is that rain was spoiling the fun.

On harder surfaces rainwater collects in puddles and stops a rolling ball. With felt, rain can be absorbed into the ground.

Nowadays, the World Minigolf Sport Federation approves four different types of course and surface.

Fibre cement, or eternite, courses are the most popular worldwide. Players cannot stand on the surface, but the holes are very short. More than 1,000 players have officially recorded a perfect 18 on this type of course.

Nowhere else have 18 consecutive aces been scored in national or international tournaments.

So the quest for perfection remains on the rest: the beton concrete courses of Switzerland, Austria and southern Germany, the felt courses of Sweden and Finland, and the artificial grass of the UK and the US.

The world federation is on a quest too. It has an official strategic goal of “working towards inclusion in international multi-sports games”. In other words, the Olympics.

Anyone tempted to train for potential Olympic glory may want a course at home. A self-assembly “supersize” nine-hole crazy golf course, with assorted obstacles, 18 putters, 18 balls and 1,000 scorecards certainly sounds like the ultimate kidult gift.

But it does not come at pocket money prices. It is yours for £3,000.

More affordable, perhaps, is hiring a four-hole course for just over £200.

Selling and renting these courses is Putter Fingers, a business based in Thetford in Norfolk, which bizarrely is an off-shoot of a software company which started selling courses mainly to show off its ability to make websites.

“The business of crazy golf has a fair bit of growth left in it,” says logistics manager Richard Clarke, explaining that putters are the biggest seller.

Schools, corporate event organisers, couples looking to entertain their guests at a wedding, and birthday entertainers are all regular customers.

But the really crazy money is being made in big cities like London – all because of a phenomenon called competitive socialising.

People playing at golf activity bar, Swingers, West End. PHOTO: Luke Dyson /Swingers

People playing at golf activity bar, Swingers, West End. PHOTO: Luke Dyson /Swingers

“People don’t just want to go to a restaurant or a bar and just eat or drink, they want something else,” says Matt Grech-Smith, co-founder of the crazy golf activity bar Swingers, which employs 250 people.

“Social media is playing a role in that. People want to show off the experiences they are having. Something visually appealing works.”

Swingers – with a name squarely aimed at its over-18 clientele – has two sites in London, a turnover of £18m a year, and a “healthy” profit margin, according to Mr Grech-Smith. The next market to crack, he says, is that original minigolf mecca - New York.

Each site has two nine-hole courses, not-so-subtle mid-round bars to replenish visitors, and choice of meals from burgers to burritos. People typically spend £30 to £50 a night – a lot more than they would for a game of crazy golf and chips on the beach in Hastings.

Even early on a Wednesday afternoon there was huge corporate group eating pizza, drinking beer, and cheering or bemoaning each other’s putting skills. The booze would get them disqualified from official minigolf tournaments, but it is integral to these adult-only venues.

To the converted, including some commercial landlords, this kind of place is a saviour for the troubled High Street. The theory is strengthened by the fact that Swingers is located in the old flagship store of collapsed retail giant BHS.

People playing at golf activity bar, Swingers, West End. PHOTO: Luke Dyson /Swingers

People playing at golf activity bar, Swingers, West End. PHOTO: Luke Dyson /Swingers

Elsewhere, the owner of Paradise Island Adventure Golf – which has seven indoor courses in UK shopping centres – was bought in late 2017 for more than £10m.

The worlds of retail and entertainment are colliding, and are in direct competition with the theatre, concerts, and even home entertainment like Netflix, says Mr Grech-Smith.

“Lots of retail brands are making their shopping experience much more immersive and experience based. The tastes of the consumer are clearly changing,” he says.

“Those destinations that can offer as many different experiences as possible are going to win.”

To the less convinced, competitive socialising faces an uphill struggle in attracting repeat visitors.

But, for now, business is booming and the game has momentum.

The St Andrews Ladies' Putting Club started the ball rolling, it gathered pace in the US in the 1920s, was carried forward by enthusiasts across Europe, and has landed straight into the social media feeds of millennials enjoying a competitive night out.

Plenty of economic obstacles may stop this becoming a second golden age for the game.

But there are supposed to be obstacles. This is crazy golf.