Birmingham Pub Bombings: Conflict and Conspiracy

Told by the people caught up in the nightmare

The Inside Story of the Birmingham Pub Bombings

The pain of Britain's biggest unsolved mass murder is still raw 50 years on

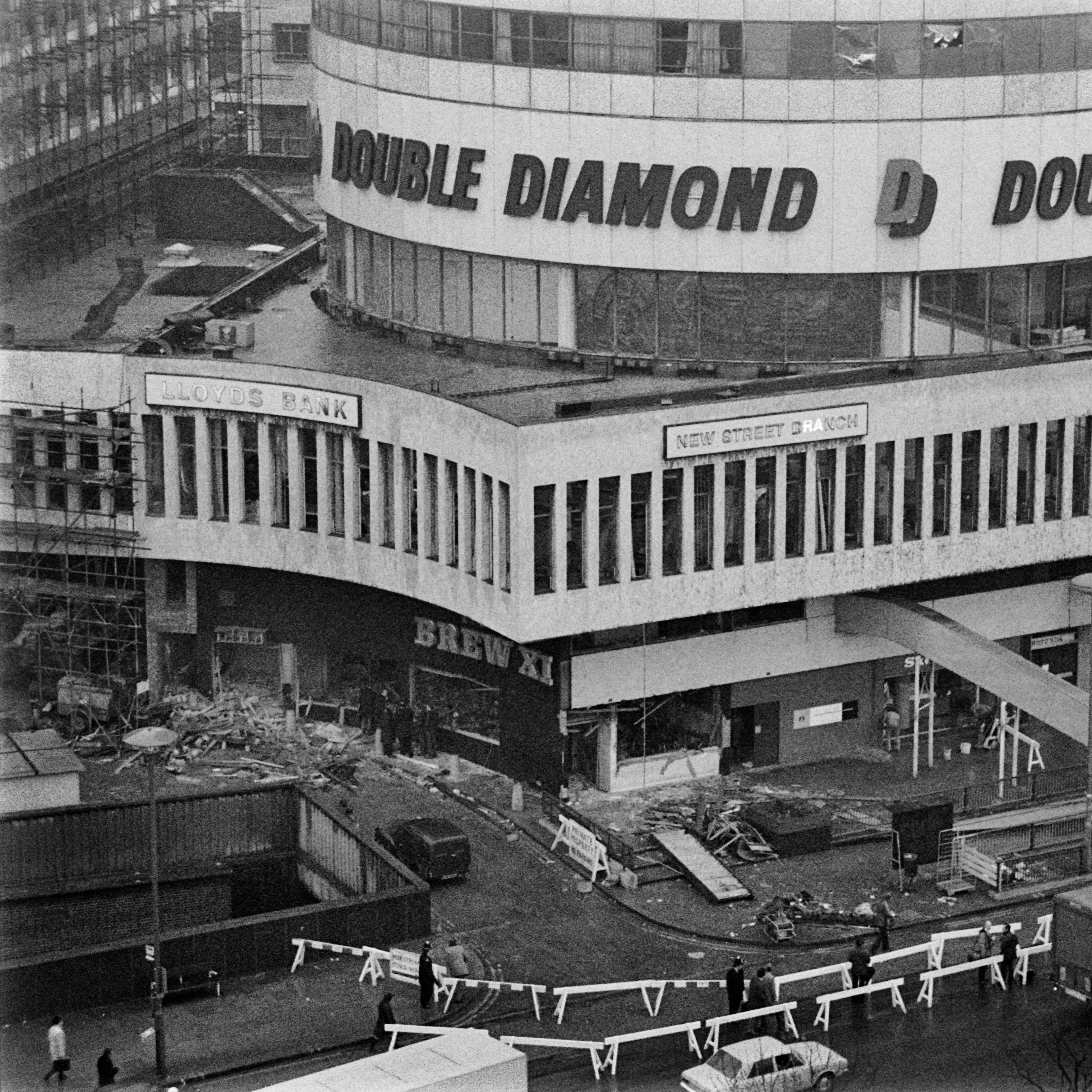

There was a buzz in Birmingham’s pubs on the evening of Thursday 21 November 1974.

While it was a miserable, foggy night, it was payday for many and the shops were open late.

New Street had not yet been pedestrianised and buses, cars and taxis cruised up and down it, dropping pub-goers close to their favourite haunts.

Regulars at the Mulberry Bush pub nodded to one another over their drinks. Meanwhile, the underground bar The Tavern in the Town was filling up with a younger crowd.

There had been tension earlier in the day over the repatriation of an IRA bomber from Birmingham Airport, but nobody expected trouble in the city.

But, shortly after 20:00 GMT, bombs exploded in both pubs, bringing mass murder to the streets of Birmingham.

The bombings remain one of the deadliest acts ever carried out on British soil, but, to this day, the true perpetrators have not faced justice.

The BBC has spoken to survivors, the wrongly accused and those still seeking answers in a new series for BBC Sounds, In Detail ... The Pub Bombings.

The Survivor

Maureen Mitchell was having a drink with her fiancé in the Mulberry Bush when an IRA bomb detonated. She was carried out in agony, convinced she would die.

The Son

Paul Bridgewater never met his father, who was killed in the bombings. He is fighting alongside other families for the full truth about what happened.

The Reporter

Veteran TV reporter Michael Buerk arrived at the horrific scene within hours of the explosions. He wishes he had been more sceptical after the Birmingham Six were jailed.

The Wrongly Convicted

Billy Power spent 16-and-a-half years in jail, wrongfully convicted of the attacks. But he believes the victims and their families have faced a graver injustice.

The Daughter

Billy Power’s daughter Breda was eight when the attacks happened. She learned her father had been arrested from a TV news flash.

The Irishman

Frank Foley was one of many Irish Brummies to experience a backlash after the atrocity. He was also interviewed by the police after they received an anonymous tip-off saying he was involved.

The Survivor

The interior of the Mulberry Bush pub following the bombing.

The interior of the Mulberry Bush pub following the bombing.

Maureen Mitchell nipped home from work for tea before heading back out to meet her fiancé, Ian. Since they both lived with their parents, they caught up in Birmingham most nights.

It was about 19:30 GMT as the couple threaded their way to their regular haunt, a pub on the ground floor of the city’s the iconic high rise Rotunda building called the Mulberry Bush.

There was a nip in the air, but Ian was snug in a new sheepskin coat, bought with savings supposed to be set aside for their wedding in June.

At the bar, the couple nodded hello to an acquaintance, Stanley Bodman, and told him they would join him for a drink in a moment.

First, Maureen needed to break it to Ian he could not attend her work Christmas do and took him to a quiet spot under a staircase in the middle of the room.

As she was speaking, she experienced a flash of light from the blast, then found herself floating through the air.

Although she did not hear the bomb detonate, Maureen recalls the screaming in its aftermath and Ian’s voice as he searched for her through burning rubble.

Shrapnel had punctured her hip and lodged in her bowel. Ian and a security guard managed to drag her to safety but, as she lay propped in agony against a wall by the station, she thought that was it.

“If I die, remember I love you,” she told Ian.

At the city’s General Hospital, a priest read her last rites. She remembers her dad sobbing at her bedside and, later a visit from Prince Phillip.

“He said: ‘hello, how are you?’ I said: ‘I’m alright, thank you, how are you?’ And I’m thinking, I’m lying with all these tubes and monitors and things and I’m saying, I’m alright, how are you?”

Despite her injuries, she survived and was eventually discharged just before Christmas.

But, Stanley Bodman had been killed instantly, one of 21 victims of the blasts.

Ian had suffered serious wounds to his face and legs, but his sheepskin coat had shielded his body. Maureen says: “It was probably the best £80 we ever spent.”

Though she still bears physical scars, she says she processed the trauma years ago.

“They saved me,” she says. “I was one of the lucky ones.”

The Son

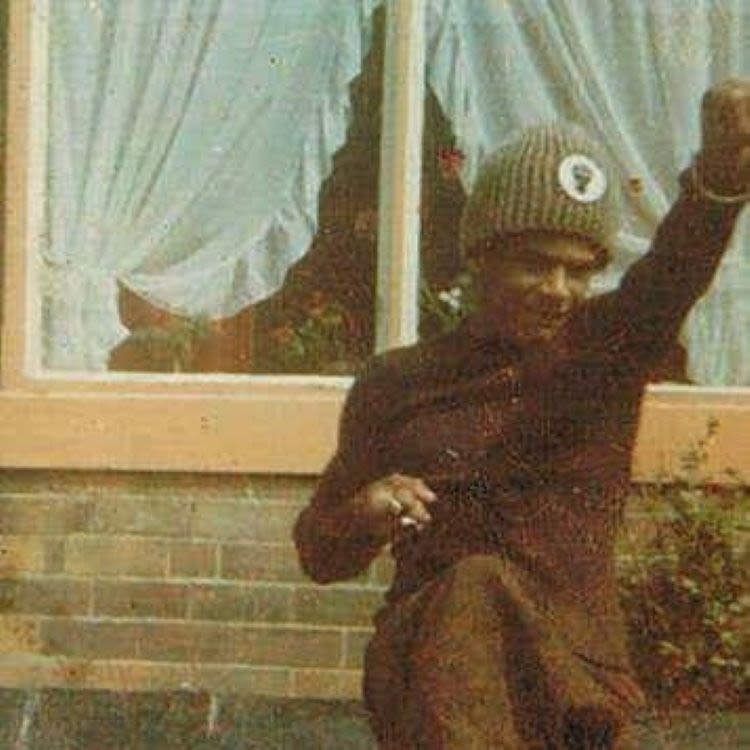

Everything Paul Bridgewater knows about his dad is pieced together from other people’s memories.

Martial-arts-loving Aston Villa fan Paul Anthony Davies, 17, was killed in the bombings three months before he was born.

“He was a black belt at karate, quite a physical, athletic guy,” Paul says. “Very popular with the ladies, I’m told, as well.

“A bit of a character.”

On the night he died, he had gone to a youth club with his friend Neil Marsh, 16. Finding it shut, they walked into town to meet some girls and were killed as they walked past the Mulberry Bush.

Paul’s mother would put her lost love on a pedestal. “She’s never got over it,” he says. “As a kid, knowing that I didn’t have my father there… it just had a massive impact on me and my mom.”

Paul grew up believing the Birmingham Six were responsible for his dad’s death, and was shocked when they were acquitted. “There was no thought to my mother, and I imagine none of the other families as well,” he says.

In his 20s, he moved from Birmingham to Yorkshire. One day, he got email from a woman claiming to be his niece and learned he had a half-sister, Michelle.

“I remember her coming through the door and I've got a picture of my dad on the wall,” he says. “She just went, ‘oh my God’, ‘cause she'd never seen the picture before.”

He got back in touch with an aunt he had not seen since he was a toddler, which filled in more missing pieces.

“It was amazing to just find all this stuff that had sort of been lost,” he says.

Photos show his dad in a pair of classic Adidas 3-stripes trainers. Paul is an Adidas collector, with more than 100 pairs. “I didn’t know before I saw that picture,” he says. “He just must have passed it on.”

He is fighting alongside other bereaved families for the full truth about the death of his father, a teenager who wore bell bottoms to practise his kicks.

“In the paper, my dad had always been a black silhouette,” he says. “Meeting all the family members and they'd all experienced similar things. It opened that book again, that I thought was closed.”

Paul Anthony Davies was a big fan of karate movies.

Paul Anthony Davies was a big fan of karate movies.

The Wrongly Convicted

The Birmingham Six, with MP Chris Mullin in the centre, on the day of their release in 1991. Billy is on the far right.

The Birmingham Six, with MP Chris Mullin in the centre, on the day of their release in 1991. Billy is on the far right.

For just a moment, Billy Power wavered.

He was about to leave his house for the funeral of James McDade in Belfast.

The IRA man had blown himself up while planting a bomb in Coventry. Despite the circumstances, Billy had known him well and it was expected he would pay his respects.

But, watching the news, he saw there had been unrest during McDade’s repatriation.

“For a moment, I decided I wasn't going to go. I said there may be too much trouble,” he recalls.

His wife, Nora, told him to get a move on and the moment passed.

At Birmingham New Street Station he caught a train with Paddy Hill, Richard McIlkenny, Gerard Hunter and John Walker.

They left Birmingham about 20 minutes before the bomb at the Mulberry Bush exploded. Within hours, Billy would confess to planting it.

He recalls being “brutalised” in police custody after forensic tests appeared to show he had handled explosives.

“First I know was I got a punch in the back of the head. Threw me forward and was just shouting at me: ‘You dirty, murdering bastard’.”

During hours of questioning, a “heavy mob” periodically yelled further abuse and threats.

“It was easier, psychologically and physically, to agree to it and put a signature to it,” he says.

Billy views himself and the rest of the Birmingham Six as scapegoats.

“We could never have got a fair trial, no matter what,” he says. “We might as well have just sat in the dock with a paper bag over our heads.”

When he went to jail he was 29, by the time he was acquitted he was a grandfather.

“Sometimes I feel I've got more bonding with my grandchildren than I had with my own children,” he says.

He looks back with surprising fondness on “uncomplicated” prison life, where he was regularly visited by nuns.

“It was a spiritual experience in prison that I haven't felt since I've come out,” he says.

Despite his ordeal, he maintains a graver injustice was suffered by the victims and, doubly so, their families.

“They had their loved ones blown to bits, and then the wrong people convicted for it.

“Can you just imagine having to go through that?”

He would like a quiet life with his family, but his case is too notorious.

“It never goes away,” he says. “There'll never be closure.”

The Daughter

“They say that, after a traumatic event, you can have no memory of your life before it. That’s what happened to me.”

On the Sunday after the bombing, eight-year-old Breda Power was allowed to stay up late to see her dad arrive home from Belfast.

The family had heard about the explosions but had no idea Billy was a suspect.

She vividly remembers his picture flashing up on the news, alongside those of the five other members of the Birmingham Six.

“I just started crying because I thought it meant that my dad was dead,” she says. “I thought he'd died in the atrocities.”

Her mum, Nora, ran out of the house in shock.

The next day, Breda and her sister were on a plane to Cork to stay with their aunt.

“It was just horrendous, when I look back at it. Very traumatic,” she says.

Her childhood was dominated by prison visits. Extended family would fight over who got to go, meaning Billy was never short of callers.

For a time, Nora would wake the children at 05:00 to travel to a jail on the Isle of Wight. At 16, Breda was security cleared to visit him by herself.

“I had to grow up very fast,” she says. “There was a lot of responsibility on my shoulders from a young age.”

In 1985, the first of three ITV World in Action programmes aired, in which journalist Chris Mullin cast doubt on the Six’s convictions.

It was a turning point, Breda says. “Within days, we had a campaign of people that were just outraged.”

Entertainers and politicians lined up to offer support. As the campaign snowballed, Breda was even invited to meet President Gorbachev in the former Soviet Union, though the visit was cancelled after an earthquake.

“We met so many people, and so many people supported us at that time. It was amazing,” she says.

Eventually, after Mullin’s work helped erode the so-called evidence, in 1991 Billy and the others walked free.

“We lived on a high for the first couple of years,” Breda says. “There was a lot of adrenaline, there was a lot of demand for the men.”

Now, at 58, she works for an organisation supporting Irish prisoners and regularly visits a jail that once held her dad.

“As cliched as it is, it's that giving back,” she says. “We had six, seven years of people who literally gave up their lives to help campaign, and I was in awe of those people.

“I'm now in a position where I can help other people who are having a difficult time.”

Breda in the 1980s.

A march in support of the Birmingham Six in Dublin.

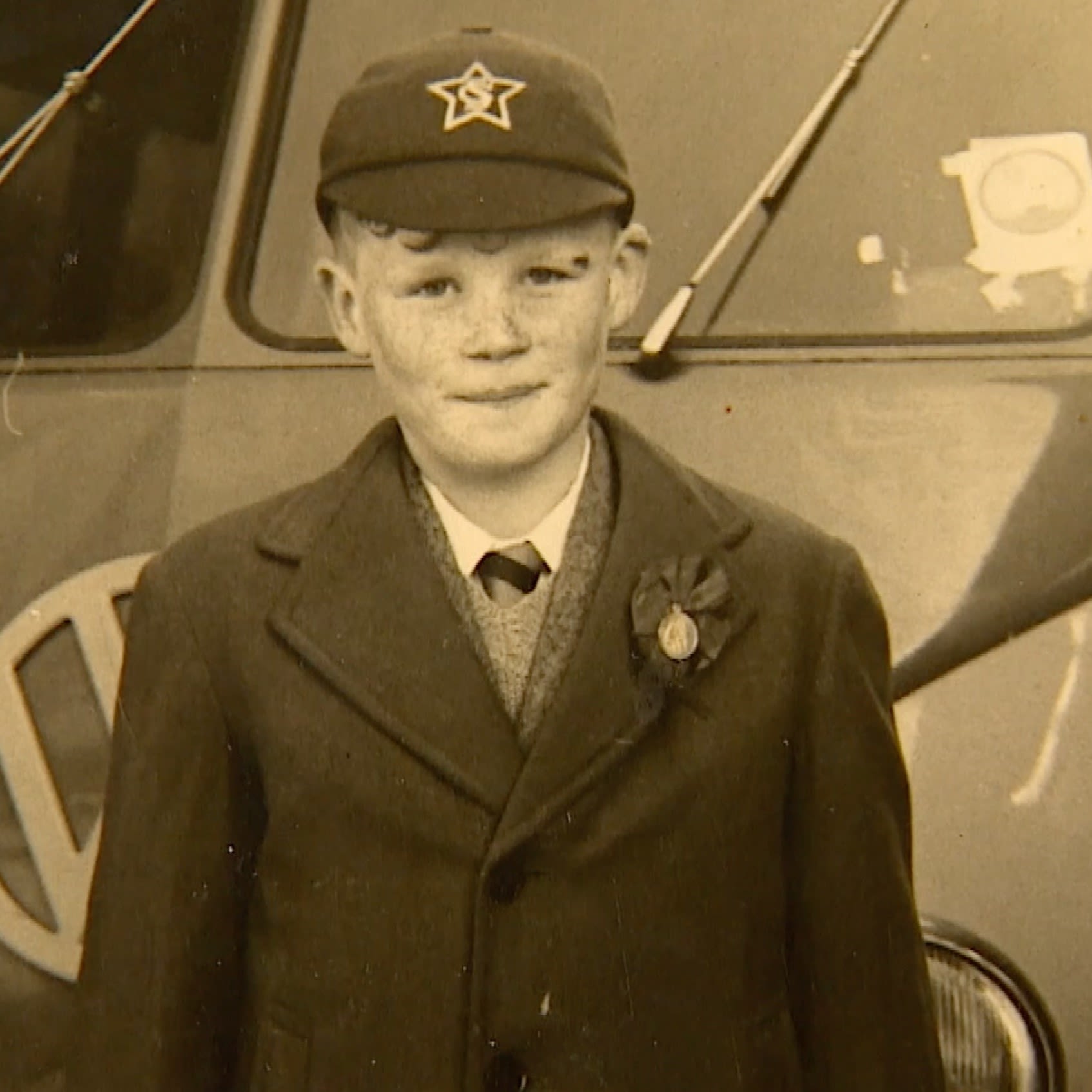

The Irishman

Frank arrived in Birmingham when he was 13 years old.

Frank arrived in Birmingham when he was 13 years old.

Frank Foley will not forget how acquaintances turned on him in the aftermath of the bombings.

The native Dubliner arrived home from a work trip abroad to find his wife, Maureen, red-eyed while nursing their cranky baby.

“Special branch had been in the house for hours,” he explains. “Hours questioning her about who I was, where I was, what was I doing, why was I there, and they were not very pleasant.”

Frank had lived in Birmingham since he was 13 and felt part of a thriving and established community.

“We were able to be Irish and also Brummies,” he says. “With an established life and so on, but still retaining the Irish culture.”

But, in the days after the pubs were hit, the Irish Brummie had become a suspect.

Incensed, despite the late hour, Frank called police to demand answers.

The following morning, two “scary” detectives met him at work. “It was very tense and aggressive,” he recalls.

He was told an anonymous caller had mentioned him by name, in one of “many hundreds” of tip-offs received since the attacks.

Frank says the officer told him: “It could be a neighbour. It could be somebody you work with. It could be a friend who did it for a joke.”

Franks remembers attacks on Irish homes and businesses and Longbridge workers walking out in protest at Irish workers in their midst.

“Even to this day I can’t believe that happened,” Frank says. “It was there all the time. They hate us. They must have hated us beforehand. Why?”

“It was deeply uncomfortable,” he adds. “You know, ‘Irish pigs go back’.”

The conviction of the Six deepened his fear the community rift would never heal.

“Oh God, are we going back to that mentality of the outsider, the foreigner, the difficulty?”

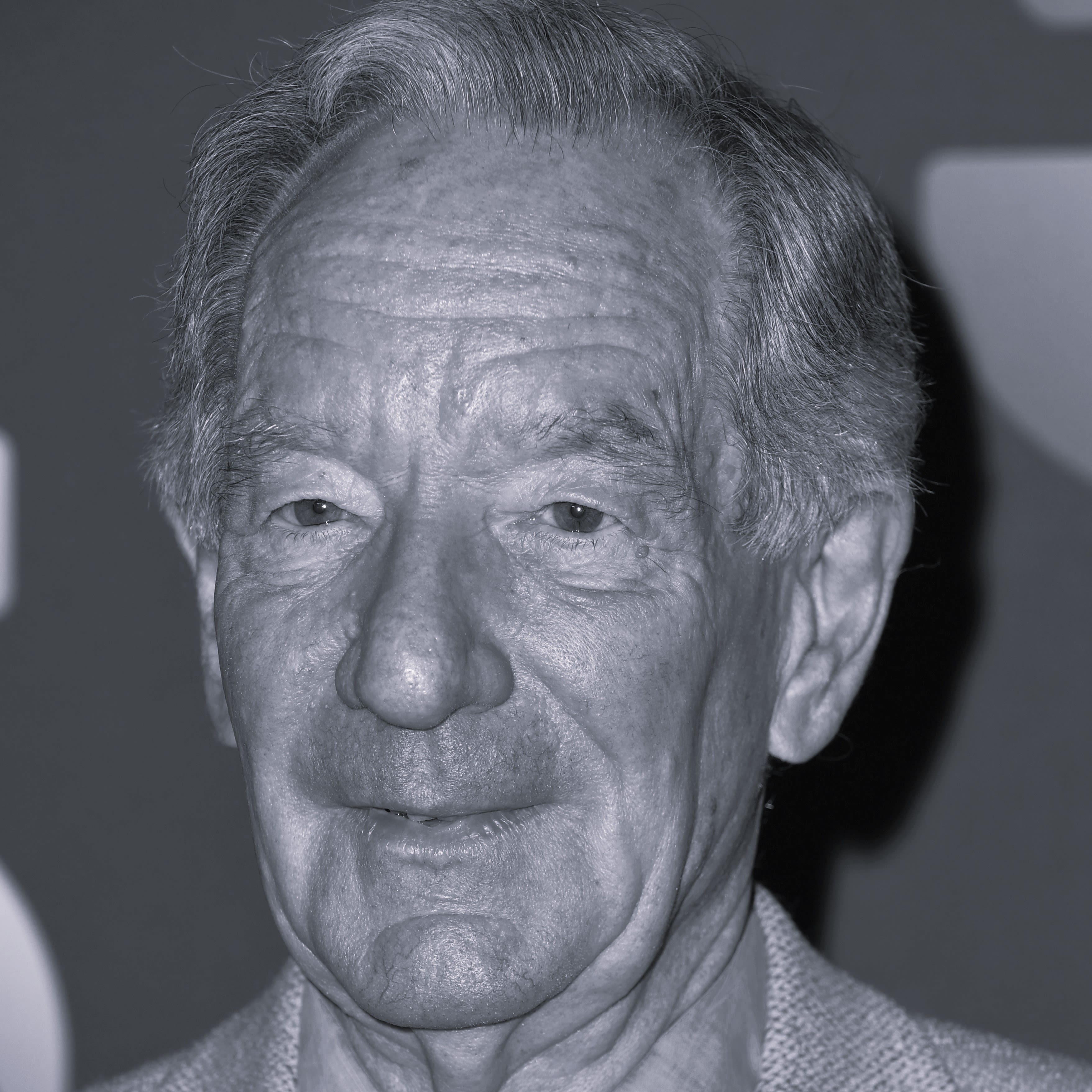

The Reporter

Michael Buerk was in the BBC's London newsroom when all the phones began ringing.

Within minutes of hearing that Birmingham had been bombed he and a film crew were on the motorway.

He had grown up on the city’s outskirts, drinking in pubs near the Rotunda.

He arrived at the Mulberry Bush to find a cavernous hole, body bags and the stench of charred flesh.

“I have a distinct recollection of a man in a double-breasted blue blazer with a lot of blood on him,” he says. “Crying outside, outside the ruins of this place.”

At the Tavern in the Town, some of the dead had been blasted through a wall. Their bodies remained inside until electrics could be made safe.

Later, Buerk got into a taxi commandeered to run victims to the hospital, and found its seats covered in blood.

At hospital, doctors described the maimed and burned victims they had tried to save, some of whom were “unrecognisable”.

Buerk says what he witnessed, coupled with evidence he would go on to hear in court, roused his antagonism towards the six Irishmen accused of the bombings.

He covered their trial amid extraordinary security.

“There were a hundred armed police with dogs,” he remembers. “I had to go through six separate checkpoints.”

“The horrors of, and the reality of what happened in the explosion… Even if you were trying to be the dispassionate observer of the whole thing, didn't make you feel disposed towards those people,” he says.

Forensic and circumstantial evidence appeared conclusive and four of the men had confessed. Few in the court had any doubt the right men had been caught.

“The entire nation, or at least that bit of it that wasn't sympathetic to the IRA cause, was feeling pretty strongly the same way,” Buerk recalls.

After the Birmingham Six were found guilty, Buerk drank champagne in a hotel as he watched his film about the case go out on the 9 o‘clock news.

“I felt extraordinarily pleased with myself,” he remembers. “This film that I made just added to the conclusive feeling that they had committed this ghastly crime and now they were going to pay for it.

“Looking back on it, we should have asked more questions. We should have been more sceptical.”

Michael Buerk reporting from Birmingham the day after the bombings.

Michael Buerk reporting from Birmingham the day after the bombings.

These accounts were all taken from the series In Detail...The Pub Bombings, available now on BBC Sounds.

Why Britain's biggest unsolved mass murder is being revisted 50 years on

Credits:

Lead Writer: Susie Rack

Online Production: Lauren Woodhead

Sub Editor: Tom Darby

Editor: Ed Barlow

Images: Getty Images, BBC Images