When blacksmiths were dentists

- Published

A cartoon showing a tooth extraction

Growing your own teeth from stem cells might seem blue-sky thinking, but dentists are confident this will become a reality within the next 50 years.

It all seems a far cry from the days when just pulling a tooth was fraught with danger and when barbers, wig makers and even blacksmiths would dabble in dentistry.

This year the dental establishment celebrates 150 years since the first dental licence.

To mark the occasion, the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) in London is holding an exhibition to mark the life and career of Sir John Tomes, the first person to officially register himself as a 'dentist'.

Milly Farrell, assistant curator of the museums department at the RCS, said Tomes had been a true pioneer in all aspects of dental care - from plotting biology of the teeth to developing instruments and furniture.

He even kept a register at the hospital of every case he treated and used these to analyse which teeth were most at risk of disease.

"Tomes developed a dental chair as well as many different instruments to deal with each tooth. He made the whole process much easier," she said.

Painful procedure

Stanley Gelbier, professor in the history of dentistry at King's College London Dental Institute, said that before Tomes, things could be very painful.

"Extractions were by forceps or commonly keys, rather like a door key," he said.

"When rotated it gripped the tooth tightly. This extracted the tooth - and usually gum and bone with it.

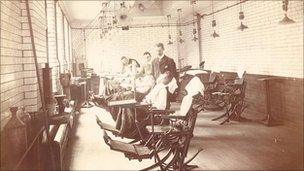

Students at work in the national dental hospital in 1905

"Sometimes the jaws were also broken during an extraction by untrained people."

Professor Derrick Wilmott, dean of faculty at the RCS, said that after the 19th century dentistry became more organised. But he said one of the big advances had been anaesthetics.

"When I qualified at the end of the 1960s it was very different," he said.

"We used to give anaesthetics with the patient still sitting up, which is quite dangerous. Now they either give local anaesthetics or sedation."

He said even in the 1960s treatment was reactive and patients would usually only turn up when they were in pain.

"Now most decay can be prevented," he said.

Future hopes

Paul King, consultant and specialist in restorative dentistry at Bristol Dental Hospital, agreed the emphasis had moved to prevention.

"A generation before it was about getting rid of disease mainly by extraction and replacing teeth where appropriate with plastic dentures," he said.

"Now, partly because we have a generation coming through who have managed to retain their teeth, there is an increasing demand not just to accept teeth extraction which has driven innovative techniques regarding materials and things like that.

"There has been more emphasis on rebuilding teeth with white fillings and replacing missing teeth with dental implants."

But he said the future hopes were even more exciting.

"The real blue-sky thinking over the next 20 years is increasing the role of the computer to make it more accurate," he said.

"X-ray scanners now do 3D scans of mouth and bone and tissues, and from that you can computer manufacture missing teeth.

"We are already using quite a lot of that, but that will become commonplace.

"But if you are looking at 50 years on, I think we will become more knowledgeable about restorative dental techniques. They have already grown teeth, albeit only in mice. If we have to replace teeth the blue sky is we will be doing it by biological regeneration."

Sir John Tomes: Victorian Dental Pioneer is at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS), 35-43 Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, WC2A 3PE, until September 25.