Vaccine patch may replace needles

- Published

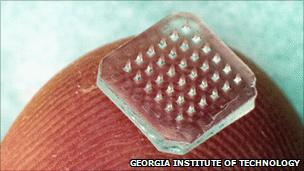

The patch has hundreds of tiny needles

A vaccine patch could cut out the need for painful needles and boost the effectiveness of immunisation against diseases like flu, say US researchers.

The patch has hundreds of microscopic needles which dissolve into the skin.

Tests in mice show the technology may even produce a better immune response than a conventional jab.

Writing in Nature Medicine, the team of researchers said the patch could one day enable people to vaccinate themselves.

Each patch, developed by researchers at Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology, contains 100 "microneedles" which are just 0.65mm in length.

They are designed to penetrate the outer layers of skin, dissolving on contact.

To test the technology, the researchers loaded the needles with an influenza vaccine.

One group of mice received the influenza vaccine using traditional hypodermic needles and another group were vaccinated with the patch.

Patches that had no vaccine on them were applied to a third group of mice.

Three months down the line the team found the patch appeared to produce a more effective immune response in mice, then infected with the flu virus, than a standard vaccination.

Apply at home

If proven to be effective in further trials, the patch would mean an end to the need for medical training to deliver vaccines and turn vaccination into a painless procedure that people could do themselves.

It could also simplify large-scale vaccination during a pandemic, the researchers said.

Although the study only looked at flu vaccine, it is hoped the technology could be useful for other immunisations and would not cost any more than using a needle.

"We envision people getting the patch in the mail or at a pharmacy and then self-administering it at home," said Sean Sullivan, the study lead from Georgia Tech.

"Because the microneedles on the patch dissolve away into the skin, there would be no dangerous sharp needles left over."

Co-author, Professor Richard Compans from Emory University Medical School, said the vaccine does not have to penetrate deeply because there are immune cells present just below the surface of the skin.

"We hope there could be some studies in humans within the next couple of years," he said.