Migraine cause 'identified' as genetic defect

- Published

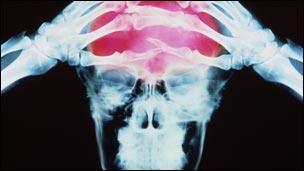

Migraines cause throbbing pain

Scientists have identified a genetic defect linked to migraine which could provide a target for new treatments.

A flawed gene found in a family of migraine sufferers could help trigger the severe headaches, a study in Nature Medicine suggests.

Dr Zameel Cader of the University of Oxford said the discovery was a step forward in understanding why one in five people suffers from migraines.

The World Health Organization rates it as a leading cause of disability.

A migraine is a severe, long-lasting headache usually felt as a throbbing pain at the front or on one side of the head.

Some can have a warning visual disturbance, called an aura, before the start of the headache, and many people also have symptoms such as nausea and sensitivity to light during the headache itself.

Until now, the genes directly responsible for migraine have been unknown.

In this study, scientists including some from the Medical Research Council's Functional Genomics Unit at the University of Oxford found a gene known as TRESK was directly attributable as a cause of migraine in some patients.

'Activate' gene

The study found that if the gene does not work properly, environmental factors can more easily trigger pain centres in the brain and cause a severe headache.

The international team used DNA samples from families with common migraine to identify the defective gene.

Dr Aarno Palotie, from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, said the breakthrough could eventually lead to new drugs which could switch off the pain of migraines.

"It opens new avenues for planning new research which possibly could then lead to new treatments... but of course it's a long road."

Dr Cader, one of the MRC researchers involved in the study, said: "Previous studies have identified parts of our DNA that increase the risk in the general population, but have not found genes which can be directly responsible for common migraine.

"What we've found is that migraines seem to depend on how excitable our nerves are in specific parts of the brain.

"Finding the key player which controls this excitability will give us a real opportunity to find a new way to fight migraines and improve the quality of life for those suffering."

He told the BBC's Today programme the research showed the defective gene in migraine patients was under-active, therefore causing the headaches.

"So what we want to do is find a drug that will activate the gene," he added.

Professor Peter Goadsby, trustee of The Migraine Trust, said: "The identification of a mutation in a gene for the potassium channel in a family with migraine with aura provides both a further important part of the puzzle in understanding the biology of migraine, and a novel direction to consider new therapies in this very disabling condition."