Implanted chip 'allows blind people to detect objects'

- Published

A man with an inherited form of blindness has been able to identify letters and a clock face using a pioneering implant, researchers say.

Miikka Terho, 46, from Finland, was fitted with an experimental chip behind his retina in Germany. Success was also reported in other patients.

The chip allows a patient to detect objects with their eyes, unlike a rival approach that uses an external camera.

Details of the work are in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Professor Eberhart Zrenner, of Germany's University of Tuebingen, and colleagues at private company Retina Implant AG initially tested their sub-retinal chip on 11 people.

Some noticed no improvement as their condition was too advanced to benefit from the implant, but a majority were able to pick out bright objects, Prof Zrenner told the BBC.

However, it was only when the chip was placed further behind the retina, in the central macular area in three people, that they achieved the best results.

Two of these had lost their vision because of the inherited condition retinitis pigmentosa, or RP, the other because of a related inherited condition called choroideraemia.

RP leads to the progressive degeneration of cells in the eye's retina, resulting in night blindness, tunnel vision and then usually permanent blindness. The symptoms can begin from early childhood.

The best results were achieved with Mr Terho, who was able to recognise cutlery and a mug on a table, a clock face and discern seven different shades of grey. He was also able to move around a room independently and approach people.

In further tests he read large letters set out before him, including his name, which had been deliberately misspelled. He soon noticed it had been spelt in the same way as the Finnish racing driver Mika Hakkinnen.

"Three or four days after the implantation, when everything was healed, I was like wow, there's activity," he told the BBC from his home in Finland.

"Right after that, if my eye hit the light, then I was able to see flashes, some activity which I hadn't had.

"Then day after day when we started working with it, practising, then I started seeing better and better all the time."

Soon Mr Terho was able to read letters by training his mind to bring the component lines that comprised the letters together.

The prototype implant has now been removed, but he has been promised an upgraded version soon. He says it can make a difference to his life.

"What I realised in those days was that it was such a great feeling to focus on something," he says.

"Even having a limited ability to see with the chip, it will be good for orientation, either walking somewhere or being able to see that something is before you even if you don't see all the tiny details of the object."

Electrical impulses

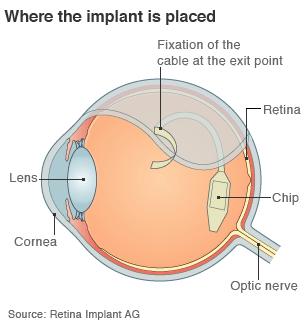

The chip works by converting light that enters the eye into electrical impulses which are fed into the optic nerve behind the eye.

It is externally powered and in the initial study was connected to a cable which protruded from the skin behind the ear to connect with a battery.

The team are now testing an upgrade in which the device is all contained beneath the skin, with power delivered though the skin via an external device that clips behind the ear.

This is by no means the only approach being taken by scientists to try to restore some visual ability to people with retinal dysfunction - what's called retinal dystrophy.

A rival chip by US-based Second Sight that sits on top of the retina has already been implanted in patients, but that technique requires the patient to be fitted with a camera fixed to a pair of glasses.

Charities gave the news of the latest work a cautious welcome.

David Head, of the British Retinitis Pigmentosa Society, said: "It's really fascinating work, but it doesn't restore vision. It rather gives people signals which help them to interpret."