'My unusual cancer'

- Published

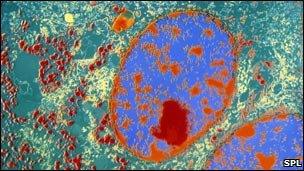

Neuroendocrine tumours can be hard to diagnose

Philippe Parker has a very rare cancer - so rare few have heard of it.

He was diagnosed with neuroendocrine cancer - which starts in hormone-producing nerve cells. They usually occur in the digestive system but can occur in other parts of the body.

Philippe, who is from London, was lucky. He was diagnosed six months after his first symptoms, including abdominal pains and itching caused by jaundice appeared. But others with the cancer waited around five years to find out what is wrong.

An ultrasound scan revealed Philippe, 39, had a blockage in his pancreas - and most of it had to be removed.

"At first they thought I had contracted something like hepatitis on holiday, or an inflammation," he said.

"But I had a blockage. A tumour.

"The tumour was unusual and difficult to determine. It took quite a while before I could get a biopsy."

When he did it confirmed that Philippe had cancer.

Janet French, of the Association for Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Disorders (AMEND), agreed that getting an accurate diagnosis is difficult.

"From a recent survey we found that on average patients visited GPs 30 times before getting referral," she said.

"Patients had an average of 15 referrals; saw an average of 10 different consultants or doctors in hospital and required an average of 15 visits to get a diagnosis."

She added: "There is a lack of knowledge in all sectors of the NHS, and a patient needs to be treated in a specialist centre where they actually stand a chance of the medical staff having heard of it and know the right things to do and when to do them."

Philippe is now being treated at the Royal Free Hospital in London with interferon therapy, a type of drug therapy which stimulates the body's immune system to fight the cancer.

And although it will not cure his condition, it keeps it at bay.

"It is not really curable and not one of those cancers you can be rid of," he said.

"When it is in your endocrine system it is difficult to diagnose it is not like you go into remission you have the treatment and keep going.

"It is very intensive treatment. You stop and then repeat."

Frustration

Philippe said that the worst thing for him was not the cancer but its effects.

"It is the fact that I have very little pancreas left and have had lots of my intestines cut out and have digestive problems and the interferon has lots of side-effects.

"It is a bit like injecting yourself with flu. You get aches and weariness. It was tough the the first couple of years.

"I have been on interferon for four and a half years and almost certainly will be for the rest of my life."

And he said the rarity of the disease had proved to have a double edge: "There is is frustration because it is so rare. Everybody focuses on the effect on people, not the research.

"It does not get funding from the big organisations

"But from a patient's perspective, the advantage is that because it is so rare there is not a blanket approach to treatment."

And he said this meant a more tailored approach.

Professor Martyn Caplin, a consultant gastroenterologist who heads the Royal Free's neuroendocrine tumour unit, said raising the profile of the disease is important as more than 90% of all patients are incorrectly diagnosed and initially treated for the wrong disease

"By raising awareness, we hope these cancers will be diagnosed earlier. We have many exciting developments in terms of imaging tests and therapies, and it is important for patients with these rarer cancers to be seen in specialist centres so that the correct treatment and support can be given."