'Why you pay for other people's drinking'

- Published

Putting prices up 'would curb intake'

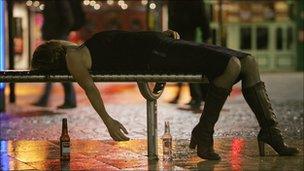

As preparations for New Year's Eve celebrations near their climax, economist Professor Anne Ludbrook argues in this week's Scrubbing Up that it is unfair that we all pay for the price for the damage caused by alcohol.

Ask yourself how you would feel if you contributed to a kitty for drinks but you didn't get a drink.

Or if another customer at the supermarket asked you to pay for part of the alcohol they were buying.

Sounds a bit far-fetched? But this is the reality of the peculiar market for alcohol. Everyone pays the price for alcohol, whether they drink themselves or not.

Alcohol related harms cost the country over £25bn (or around £500 per adult) in costs to the NHS, police and fire services, industry, the lost value of reduced health and so forth.

Supermarkets run "loss leaders" on alcohol to attract customers and make money from other items in the shopping basket - so you and I may be paying more for our grocery shopping to subsidise cheap alcohol.

Social cost

As an economist, I naturally think that markets could provide the best outcomes but only if they work properly.

That means that people who buy and consume alcohol should pay the true cost - the price of the drink and cost of future harms.

Isn't that what alcohol duty is supposed to do?

Well, duty does raise revenue but at current levels, only about a third of the amount needed.

There is also the problem that duty rates in the UK are not related to alcohol content, ranging from less than 5p per unit of alcohol for cider to over 20p per unit for spirits.

Even the duty on spirits is less than half the social cost per unit of alcohol.

Minimum pricing establishes a floor price for alcohol and could be used to make sure that no drinks are sold below the average social cost.

It would also be effective in reducing alcohol consumption and related harms.

'No silver bullet'

Research from Sweden shows that price increases targeted at the lowest cost brands would produce almost 2.5 times the reduction in alcohol consumption that an across the board price rise would.

Also, the heaviest drinkers reduce their drinking most because they tend to drink the cheaper products.

Supermarkets regularly offer cut-price deals on alcohol

Research by the University of Sheffield for the Department of Health and the National Institute for health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) shows that a minimum price of 50p per unit of alcohol would reduce alcohol consumption by 6.7% percent on average but the heaviest drinkers would reduce consumption by 10.1%.

The value of the reduced harm from alcohol would be nearly £1bn in the first year: 80% would come from the reduction in consumption by harmful drinkers.

Minimum pricing has recently failed to gain sufficient support in the Scottish Parliament to see it pass into legislation.

However, it has been recommended for consideration by NICE and by the House of Commons Health Select Committee.

The UK government's alternative proposal is to ban below-cost selling but this can be hard to define.

If it is interpreted as duty plus VAT, then the impact on average consumption may be negligible unless duty rates are both reformed and increased.

Successive governments have said they want to tackle alcohol-related harms but have pursued policies that have been ineffective.

Minimum pricing of alcohol is effective and well targeted but it is not a silver bullet.

A range of policies needs to be put in place - but trying to tackle the harms that alcohol causes without making alcohol less affordable is a bit like trying to empty a bath while the taps are still on.