Alzheimer's blood test 'fishes' for signs of disease

- Published

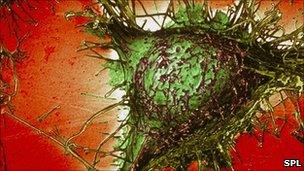

The test relies on the immune system reacting to diseased cells

A new technique could lead to a blood test for detecting Alzheimer's, a US study claims.

The small trial, published in the journal Cell, used thousands of artificial molecules to "fish" for the disease.

Researchers hope to use this method to diagnose other diseases earlier, including lung and pancreatic cancers.

The Alzheimer's Research Trust said it could result in a new test, but more research was needed.

The technique relies on the immune system's ability to recognise foreign material.

Proteins on viruses and bacteria are recognised as alien so the body produces antibodies, and the same is true for Alzheimer's.

So if you can test for the antibody, you can test for the disease - traditionally, however, this has been very hard to do.

A new approach

The team at the Florida campus of the Scripps Research Institute took blood samples from six patients with Alzheimer's, six with Parkinson's disease and six healthy individuals.

They then used 15,000 synthetic peptoids (the bait), to "fish" for antibodies.

In this very small sample size, the researchers found two antibodies which identified Alzheimer's sufferers.

Dr Simon Ridley, head of research at the Alzheimer's Research Trust, said: "This very early research poses a new way of testing blood to diagnose Alzheimer's, but much more research must be done.

"We need to know how accurate and sensitive the test is and it also needs to be trialled in larger and more diverse groups of people."

There is still no cure for Alzheimer's, but using early testing could help with finding patients for clinical trials of future treatments.

Dr Ridley believes a test will help: "Detecting Alzheimer's and other dementias early is essential to defeating the condition. We know that treatments for many diseases can be more effective if given early and this is likely to be true for dementia."

Wider applications

The method was also successful in testing mice for a condition similar to multiple sclerosis and the report's authors hope the technique can be used to detect other diseases.

Professor Thomas Kodadek, from the Scripps Research Institute, said: "If this works in Alzheimer's disease, it suggests it is a pretty general platform that may work for a lot of different diseases. Now we need to put it in the hands of disease experts to tackle diseases where early diagnosis is key.

"Of course, this kind of simple diagnostic technology would have the biggest effect in diseases where early detection will have a significant effect on therapy, for example in various cancers."

The researchers are now investigating whether the method works in lung and pancreatic cancers.

- Published22 December 2010