Development fears over half of English five-year-olds

- Published

Children are expected to be able to concentrate and share by five

Nearly half of children in England are not reaching what teachers consider a good level of development by the age of five, public health experts say.

Achieving a good level of development by five is considered to be a guide to future health prospects.

The Marmot Review team examined local authority data and found inequalities in life expectancy, how long people lived disability-free and unemployment.

The government said it wanted to improve the health of the vulnerable.

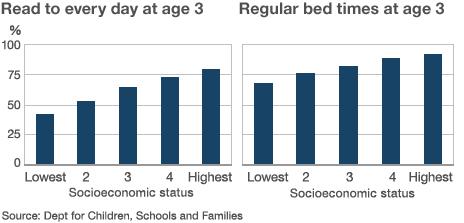

Regular bedtimes

The report's authors, who last year published a groundbreaking study of health inequalities in the UK, looked at five key indicators that are used to predict future health: life expectancy, disability-free life expectancy, child development at five, young people out of work and households on means-tested benefits.

The assessment of children's development at the age of five is based on their behaviour and understanding.

Children should be able to share, self-motivate, co-operate and concentrate by the time they start school.

But the research, led by British Medical Association president Sir Michael Marmot, found 44% of all five-year-olds in England are not considered by their teachers to have reached that level.

That percentage rises to 58% in the London Borough of Haringey, followed by 55% in Brent, Newham and the County of Herefordshire.

Solihull in the West Midlands and Richmond upon Thames have the largest percentage of children (69%) achieving a good level of development.

Child development experts say simple things like reading to children every day, regular bedtimes - even cuddling your children - will have a positive impact on their development.

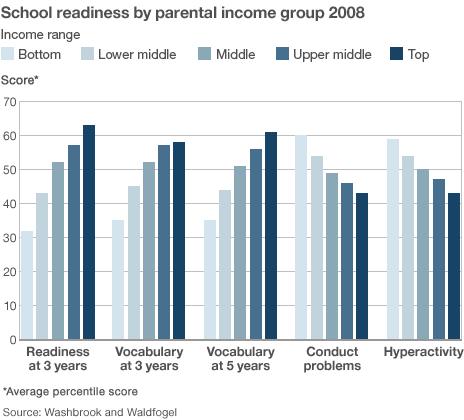

Research shows that for various reasons, poorer families are less likely to engage in these kinds of activities.

The difference in life expectancy in men between the poorest and the wealthiest - even within local council areas - is more than nine years for roughly half of the authorities in England.

For women the figure is about six years.

The gap is widest for men in Westminster at 17 years; for women it is 11 years in Halton and Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Disability-free life expectancy measures the number of years a person can expect to live free of an illness or health problem that limits their daily activities.

The difference in disability-free life expectancy between the wealthiest and poorest men is 10 years in about half the local authority areas in England; for women it is nine years.

The Wirral had the widest gap of 20 years for men and 17 years for women.

'Inexpensive intervention'

Sir Michael said health inequalities cost people's lives and health, as well as tens of billions of pounds in lost productivity, healthcare and welfare payments.

"There are cohort studies that follow children from birth right through life to adulthood, and you can see that the circumstances in early childhood affect and health and health inequalities in adult life," he told BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

"There is no question that inequalities in society are, in large measure, responsible for inequalities in early child development.

"Now, a big part of that is parenting. If parents can't parent properly because they are poor, depressed, pressed in by circumstances ... then we need to be there to support those parents.

"I suspect that a simple intervention like reading to children every day is something that, if parents can't do it, others could step in and help. It can make a huge difference."

Sir Michael added: "There are data from Canada that suggest half the deficit in readiness for school associated with low income can be reversed by reading to children daily.

"It's been put to me that these sort of recommendations we are making in straitened economic circumstances are going to be difficult, but reading to children is not an expensive intervention."

Dr John Middleton, vice-president of the Faculty of Public Health, said the new information could help local authorities target resources when they take over responsibility for public health.

"These figures provide vital information that can be used to address the deep-seated health inequalities that are present in so many communities nationwide.

"Importantly, Marmot and his team have identified poverty and unemployment as key wider determinants of health, aspects that were somewhat neglected by the government in its recent Public Health White Paper.

"The challenge is now for local authorities, working together with public health colleagues and supported by national government initiatives, to invest money and expertise in addressing these inequalities."

But public health minister Anne Milton said the government was focusing on improving the health of vulnerable groups.

"We are also providing a ring-fenced public health budget, weighted towards the most deprived areas, to make sure resources are spent on preventative work, with incentives to improve the health of the poorest, the fastest.

"We will continue to prioritise health inequalities; care cannot be described as high quality if only some people are getting a good service."