Phineas Gage: The man with a hole in his head

- Published

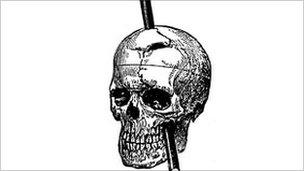

A metre-long iron rod travelled through Phineas Gage's head, emerging out of the top of his skull

"Phineas Gage had a hole in his head, and ev'ryone knew that he oughta be dead. Was it fate or blind luck, though it never came clear, kept keepin' on year after year…"

That song by banjo man Dan Lindner probably sounds like an outlandish myth, an old wives' tale passed around a small town.

But incredibly, his jaunty tune about Phineas Gage is true.

He did have a hole in his head, and against all the conceivable odds, he should have been dead. But instead, his remarkable story changed the study of neuroscience forever.

A railway worker in Vermont, US, Phineas was responsible for clearing away rocks in order for railway tracks to be laid down.

For the biggest rocks, he would drill a hole and use an iron rod to tamp down explosives into the middle before lighting the fuse.

But on 13 September 1848, this relatively simple procedure took a vicious twist. Phineas' iron rod apparently scraped the side of the rock, creating a spark which set off the gunpowder early.

It sent the iron - about 1m long and 3cm in diameter - straight up into his skull, driving through just under his left eye, and out of the top of his head, landing some 30m away.

Phineas was unconscious for a few moments before getting up and riding an oxcart into town with, the old banjo song continues, "a big bleedin' hole in his head".

Changed man

Under the expert care of local doctor John Harlow, Phineas kept on living for 12 years.

Little did he know that his momentary lapse of concentration would lead to him becoming one of the most famous case studies in brain science to this day.

Because although Phineas survived, he was a changed man. Now he was reportedly unreliable, partial to swearing and often making inappropriate remarks.

"It's reported that he became what now would be classically described as 'disinhibited' - this is a classic term for what happens to some people after damage to their frontal lobes," says John Aggleton, professor of neuroscience at Cardiff University.

"So, he loses his inhibitions, both in a social and emotional context. He would be rather high.

"Difficult company, to put it mildly."

For specialists, this was a staggering revelation. For the first time, this was evidence that damage to the brain could affect our behaviour and personality.

"When Phineas' accident occurred, there was no accepted doctrine of the brain having functions," says Malcolm Macmillan, professor of psychology at Melbourne University, and author of An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage.

"The only point of view that was opposed to that was that of the phrenologists, the people who thought that bumps on the outside of the skull indicated the organs within the brain - therefore the parts of the brain that had particular functions."

Soon after the accident, different brain specialists used evidence from Phineas' case as evidence of their own theories about the way the brain worked.

Those in favour of localisation - the idea that different parts of the brain had different tasks - said his changes in personality vindicated their position.

While others believed the fact that Phineas had survived at all showed that all parts of the brain could do everything and that one part could take over when another had failed.

Rehabilitation

Modern neuroscience would tell us that to an extent they were both right.

"It alerted people to the fact that a part of the brain - the frontal lobes - that we associate with sort of planning and intellectual strategies also had this important role in emotion," says Professor Aggleton.

"That raised the question how on earth are emotion and intellect linked together?"

Phineas' survival and rehabilitation demonstrated a theory of recovery which has influenced the treatment of frontal lobe damage today.

"There are something like 15 or 20 cases of people who've recovered from very serious frontal brain injury, of the kind that Phineas suffered from, without any professional assistance.

"In every case, what's common in the reports is that someone, or something, has taken over the lives of these people and given them structure."

In modern treatment, adding structure to tasks by, for example, mentally visualising a written list, is considered a key method in coping with frontal lobe damage.

"Phineas worked as a stage-coach driver," continues Professor MacMillan.

"The job is one that has got an external structure. You've got to be here for this part, then there's that part, then there's something else. Just as with these cases who have recovered."

In 1859, Phineas was in very poor health. He moved to San Francisco to live with his mother, brother-in-law and sister.

Phineas had epilepsy and died in 1860.

Professor MacMillan says that although we cannot be certain, it is likely that Phineas' epilepsy and subsequent death were related to his injury.

"Some of the late-term effects of that sort of traumatic brain injury is the formation of scar tissue. Scar tissue frequently becomes the point from which epilepsy develops."

Phineas was buried, the story goes, with his tamping iron.

Seven years later, he was exhumed at Dr Harlow's request - and now both his skull and the tamping iron are on display at the Harvard Medical School.