Memory cells to fight cancer

- Published

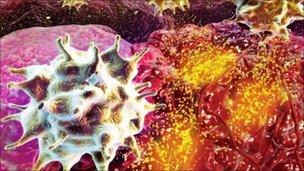

T-cells attacking a tumour

Imagine a day when doctors are able to train a patient's blood cells to fight cancer.

They take some blood, extract the white blood cells, then coax them in the laboratory to memorise the cells that cause cancer.

When injected back into the body, the memory T-cells go on to hunt and destroy tumour cells for more than a year.

For a handful of patients around the world - such a treatment has already become a reality. The hope is that in five to ten years' time, this highly experimental therapy could make the leap to approved drug.

This week, US scientists reported their results on nine patients with one of the deadliest forms of cancer.

All had advanced melanoma that had spread from the skin to other parts of the body.

Melanoma can usually be cured if detected and removed early.

But once they have spread around the body, most patients survive for less than a year.

The experimental therapy using "killer" T-cells did not stop the cancer progressing in most of the nine patients studied.

But in one, his cancers shrank and after two years they cannot be seen on scans.

These are very early days. As the researchers - led by Dr Marcus Butler of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute - point out, this is a phase I trial, and will need to be investigated in far larger numbers of patients.

But it offers a glimpse of what experimental treatments like these might one day offer cancer patients.

Dr Butler told the BBC: "Cancer-killing T-cells trained in the lab can induce long-lasting anti-cancer effects.

"The dream would be that we could make a library of killer T-cells that we could generate quickly for patients."

Immunotherapy

The approach - known as adoptive T-cell therapy - has only been studied in a few hundred patients around the world.

One obstacle is that the cells tend to disappear quickly when injected into cancer patients.

But the Dana-Farber research, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine , external, shows that the cells' life can be extended by priming them in the lab with an artificial version of cells found naturally in the immune system.

These cells inform the body's immune system that cancer is present and needs to be destroyed.

Co-author, Dr Naoto Hirano, says the next step is to study this technique in conjunction with other therapies that can boost the numbers and effectiveness of the T-cells.

He added: "We will be beginning a series of clinical trials to learn which combinations work best in which patients."

Dr Laura Bell, senior science information officer at Cancer Research UK, said the work is one of a large number of immunotherapy treatments now entering clinical trials.

"Immunotherapy is an exciting area of cancer research, designed to harness the power of the body's own immune system to fight cancer," she said.

"The results of laboratory research in this area are now starting to feed through into the clinic and we'll be following the progress of these trials with interest."