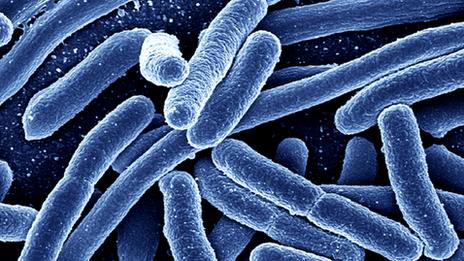

E. coli: Are the bacteria friend or foe?

- Published

E. coli are part of a large family - some bacteria in the group are more dangerous to humans than others

It is widely known for causing outbreaks of infectious diarrhoea and is currently held responsible for a number of deaths - but some scientists say E. coli has given us the answer to life itself.

"It has given us an understanding of who we are," says Carl Zimmer, who has written a biography of the bacterium.

Even before the first hour of our lives is complete, the bacterium is present in our gut in many cases, crowding out more dangerous organisms.

It lives in most other warm-blooded animals and, for the most part, is harmless.

"But some members of the E. coli family have given the group a bad name," says Mr Zimmer.

Though the strain O104 is causing severe illness and deaths in the current outbreak, there are hundreds of types of E. coli which cause us no problems.

E coli was one of the first organisms to have its genetic code sequenced - deepening our understanding of how DNA works and ultimately increasing our knowledge of how humans function.

As French scientist Jacques Monod is reported to have said, "What is true for E. coli is true for the elephant."

Many of the genetic properties that govern E. coli hold true for ourselves.

'Micro factories'

Several forms of E. coli have been modified to work for the benefit of mankind. The bacteria are currently replicating in tens of thousands of scientific institutes across the world.

E. coli is used as a micro-factory: given the right instructions, it can be modified to rapidly produce hundreds of genes or specific proteins. It is the ideal workhorse: it is easy to grow, does not require much energy, or demand sophisticated living conditions.

Even more crucial to scientists, it can be modified easily and replicates rapidly.

One of the first successes the bacterium holds to its name is the production of human insulin.

In the 1970s, scientists inserted the genes responsible for coding human insulin into the bacteria and were able to produce vast quantities of the hormone to treat diabetes.

'Birth of biotechnology'

Before this, diabetics had to rely solely on insulin isolated from sources such as horse urine and pigs' pancreases.

With this discovery, the modern biotechnology industry was born.

E. coli has been used in the production of antibiotics, vaccines and many other therapies.

And it is still used in the research and development stages of most drugs, according to Dr Stephen Smith of Trinity College, Dublin.

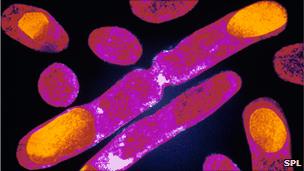

These E. coli have been engineered to produce insulin

Christopher Voigt, an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has worked with E. coli to target cancer cells.

"You can think of these bacteria as being drug delivery vehicles," he said.

"We created a strain of E. coli that can specifically bond to a molecule that is present in most malignant cancer cells and is able to deliver a therapeutic agent to the specific cell."

This work is now being continued by researchers in Berkeley who are testing the procedure in mouse models.

'Green fuel'

Christopher Voigt says medical research using E. coli is moving to a new phase - away from antibiotics which kill bacteria to engineering bacteria that are able to interact with beneficial microbes already present within us.

And E. coli's appeal has widened - engineers and computer scientists are working on it too.

Professor James Liao of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and his team recently developed a way to produce normal butanol using the bacteria.

Some consider butanol to be a greener alternative to gasoline [petrol] and other widely used fuels.

"We were able to demonstrate that E. coli can produce butanol very efficiently," he said.

Their next step will be to increase the size of the process to see how the organisms behave in large tanks, to further test its commercial viability.

'Living Computers'

A number of scientists are trying to take advantage of the digital nature of DNA in E. coli, says Dr Karmella Haynes, of Harvard Medical School.

"It has a very strict genetic code - it is almost like hardware," Dr Haynes said.

Her team's research, published in 2008, used E. coli to help them solve a problem similar to classical mathematical puzzles.

Based on their design, as each E. coli bacterium worked as a micro-computer, certain bacteria were able to solve the problem at speed, Dr Haynes said.

E. coli's applications stretch even further - by inserting genes that produce light, it has been used to make primitive cameras.

'Sinister side'

"It is an incredibly accomplished microbe, both in and out of the lab," says Mr Zimmer, author of Microcosm: E. coli and the New Science of Life.

It is this versatile nature - its ability to survive in many environments, to pick up bits of genetic code from other sources and to replicate rapidly - that also lends it a more sinister side.

It is claimed to be most studied organism on our planet. Some scientists say we know more about it than we know about ourselves.

But as new forms of infectious E. coli emerge and claim lives, there are a number of crucial experiments that still need to be done.

- Published6 June 2011

- Published4 June 2011