Mass screening for ovarian cancer 'not effective'

- Published

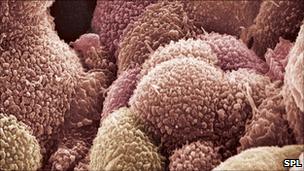

Screening did not detect cancerous cells

Screening all post-menopausal women for ovarian cancer may not reduce deaths from the disease, say researchers.

Almost 40,000 US women were checked annually over a 10-year period, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported.

During the following nine years, the number of ovarian cancer deaths matched those in an untested group of the same size.

Cancer Research UK said it was seeking new methods to detect the cancer.

While ovarian cancer is not the most common in the UK, it causes more than 4,000 deaths a year.

This is because it is often far advanced by the time that symptoms become obvious.

If caught early, up to nine out of 10 women can survive.

Two types of test are at the centre of hopes for a successful screening programme - a blood test looking for a high levels of a chemical associated with the cancer, and an ultrasound test which looks directly for abnormalities.

Unsuccessful

The University of Utah study, which started in 1993, used both tests in combination, with women given the blood test once a year for the first six years, then annual ultrasound examinations for the remaining four years.

By the time the study closed in 2010, slightly more cases of ovarian cancer had been diagnosed in the screened group, compared with the group offered no screening.

However, there were 118 deaths among the screened women, and 100 in the unscreened women, which amounted to no real difference in statistical terms.

In addition, the screening programme threw up 3,285 "false positive" results, in which the tests suggested cancer might be present, even though this was not the case.

Of these women, more than 1,000 underwent unnecessary surgery, many opting for surgical removal of one or both of their ovaries. These operations led to 222 cases of "major complications".

The researchers suggested that using a different combination of blood tests and ultrasound might improve the outcome.

However, they said that the fast-growing nature of many ovarian cancers could mean that even annual tests might not offer enough women the chance to catch it at an early stage.

A similar UK-based trial is still some years away from giving its verdict on the effectiveness of ovarian screening.

The UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) delivered encouraging results at its halfway point in 2009, with both types of test proving accurate in detecting cancers.

Like the Utah researchers, British teams are now waiting until the middle of this decade to see if this has any positive effect on overall deaths from the disease.

Dr James Brenton, an ovarian cancer specialist at Cancer Research UK, said that the charity was funding research into different methods of spotting tumours in their early stages.

He said: "This important research suggests that having a yearly ultrasound test along with a blood test, which provides a snapshot of the levels of protein associated with ovarian cancer - the serum CA125 test - is not going to cure more women.

"We are testing whether smaller rises in CA125 over time can be a better predictor, and working with international groups to identify common genes that might slightly increase the risk."

- Published27 April 2011