Heart medicine advances help patients enjoy active life

- Published

A patient recovers after cardiac arrest in the first coronary care unit in 1966

Robert Walker-Smith was eight years old when his father died of a heart attack in 1971. He has never forgotten seeing his father collapse in the hallway at home.

"I was ushered quickly away, then I saw an ambulance coming slowly along the road. I remember telling a friend, 'I think my Dad's just died'."

In the 1960s, there was no treatment for a heart attack. If they survived, victims were confined to a hospital bed, given painkillers and told to take complete rest.

If they died in their 50s or 60s, like Robert's father, it was considered a fact of life.

Knowledge of how the heart functions and how best to treat heart disease has improved dramatically over the past 50 years, says a new book written by the British Heart Foundation.

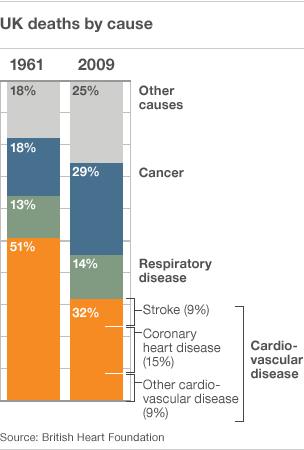

In 1961, there were 322,917 deaths from cardiovascular disease, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in the UK. Heart attacks and angina chest pain were common, but little understood.

Nearly 50 years later in 2009, UK deaths from CVD had fallen to 32%, a total of 180,626. Now the chances of having a heart attack are much less and surviving one is much more likely.

There is no mystery as to why. Smoking levels in the 1960s were high and consumption of foods loaded with saturated fats were the norm.

In half a century the average UK diet has improved and the number of smokers has declined sharply, although obesity rates continue to rise.

But it is advances in treating heart damage that have really altered the landscape of heart medicine.

Fifty years ago, heart attack victims would be lucky to be offered any treatment en route to hospital. Doctors could only cross their fingers that their patient would not go on to suffer a cardiac arrest.

If they did, their chances of survival were very low.

If they were lucky enough to be close to an operating theatre then a quick-thinking surgeon could open up their chest and massage the heart by hand to get it beating again.

It was only in the mid-1960s that the revolutionary procedure of administering regular compressions to the chest by leaning on the breastbone, not reaching inside the chest, was used to generate a heartbeat.

This simple procedure is now a basic part of first aid training.

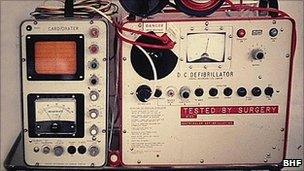

Defibrillators, a machine used to give the heart an electric shock, were in use in the 1960s, but they were extremely cumbersome.

Professor Brian Pentecost, a junior doctor at this time who later became medical director of the BHF in the 1990s, recalls his hospital's defibrillator: "It was an enormous thing known as the Red Devil, about the size of a refrigerator. It had to be wheeled through the hospital, bells ringing."

The first mobile defibrillators used by ambulance crews to treat people in their homes weighed over 11 stones and had to be powered by two car batteries.

"By the seventies you could get a defibrillator the size of a small suitcase. We could fit them in all ambulances so it was as good as being in hospital," says Prof Pentecost.

"They made a major contribution to saving lives."

Once in hospital, heart patients were scattered inefficiently throughout the general wards.

Early defibrillators were cumbersome, noisy and not very mobile

Professor Desmond Julian, medical director of the BHF from 1987 to 1993, who started working in cardiology in the 1950s, saw that something had to change.

He set up the UK's first coronary care unit in Edinburgh in the 1960s in an effort to get heart patients admitted quickly, keep them monitored continuously and keep the right equipment and staff on standby.

His example was soon followed throughout the world.

Once experts agreed in the 1970s that blood clots in blood vessels were the cause of heart attacks - and not the other way round - medicine could begin to find the drugs to tackle the problem and develop techniques to improve blood flow to the heart.

So much so that when Robert had a heart attack in 2005, aged 43, his blocked up arteries were gently opened using tightly folded balloons passed into the right location via a catheter, a procedure called an angioplasty.

Following the procedure, Robert was told to go home and stay active - not put his feet up.

He now swims three times a week and does at least two to three hours of salsa dancing and walking.

"I was lucky really. I only had minor damage to my heart. Like many people, I didn't know I'd had a heart attack.

"I went to my GP feeling awful, like I had flu. Even walking up stairs was hard work.

"He checked my pulse, gave me a blood test and an ECG then sent me home. Later I got a call telling me I had to go to hospital."

Professor Pentecost says there has been a complete change of emphasis when dealing with patients like Robert.

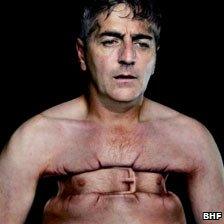

An BHF ad campaign warning people how a heart attack might feel

"Fifty years ago too many people were condemned to a life of inactivity. The treatment of angina has changed people's ability to enjoy life.

"Before, people were in bed so long they ended up with deep vein thrombosis and then got clots on the lungs."

Taking drugs to control heart disease is now a standard and effective approach.

Over one and a half million people currently living in the UK have had a heart attack. Over two million people have angina or heart failure.

The British Heart Foundation predicts that these numbers will increase as the population continues to age, making new approaches to treating heart damage very important.

Robert takes daily doses of statins, beta blockers and aspirins for his heart and will do so for the rest of his life. These drugs give him, and countless thousands of others, a good quality of life - something his father was never lucky enough to enjoy.

'50 Years at the Heart of Health, 1961-2011' is published by the British Heart Foundation. To support the Mending Broken Hearts Appeal or the British Heart Foundation, please visit www.bhf.org.uk

- Published8 June 2011

- Published29 May 2011

- Published17 February 2011

- Published9 December 2010