Faecal transplants used to cure Clostridium difficile

- Published

Transplanting faecal matter from one person to another - the thought might turn your stomach, but it could be lifesaving.

Some doctors are using the procedure to repopulate the gut with healthy bacteria, which can become unbalanced in some diseases.

Dr Alisdair MacConnachie, who thinks he is the only UK doctor to carry out the procedure for Clostridium difficle infection, describes it as a proven treatment.

He says it should be used, but only as a treatment of last resort.

The logic is simple.

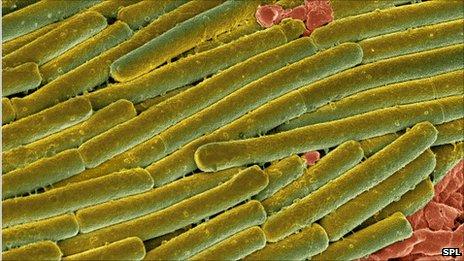

C. difficile infection is caused by antibiotics wiping out swathes of bacteria in the gut. It gives the surviving C. difficile bacteria room to explode in numbers and produce masses of toxins which lead to diarrhoea and can be fatal.

The first-choice solution, more antibiotics, does not always work and some patients develop recurrent infection.

The theory is that by adding more bacteria to the bowels, they will compete with C. difficile bacteria and control the infection.

Dr MacConnachie, from Gartnavel General Hospital in Glasgow, has performed just over 20 of the operations since he started in 2003.

"Ultimately all the patients I've treated, bar one, has got rid of their C. difficile," he said.

The procedure

If normal treatments fail to work, the patient will be given antibiotics up to the night before the operation, when their pills will be swapped for those to control stomach acid.

On the morning of the procedure, the donor will come into hospital and produce a sample.

A relative is generally used, preferably one who lives with the patient, because living in the same environment and eating the same food means they are more likely to have similar bowel bacteria.

About 30g (1oz) is taken and blitzed in a household blender with some salt water. This is poured through a coffee filter to leave a watery liquid.

Dr MacConnachie inserts a tube up the patient's nose and down to the stomach. Other doctors use a different route to the bowels.

About 30ml (1fl oz) of liquid is poured down the tube.

Symptoms of Clostridium difficile can include diarrhoea and fever

"My personal view is that this technique is there for patients who have tried all the traditional treatments," Dr MacConnachie.

"If a patient doesn't respond to that and still gets recurrent C. difficile then they're in real trouble and there isn't really any other technique or any other treatment that has the proven efficacy that faecal transplant does."

I asked him why, if that was true, were more doctors in the UK not carrying out the procedure: "It's a published technique, I guess people are scared of it.

"It sounds disgusting, it is disgusting and I think people are probably worried about approaching patients and discussing it."

That is not a problem faced by Prof Lawrence Brandt, a gastroenterologist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York.

He says he now gets between two and four emails a day from people who want a transplant. So far he has carried out the procedure 42 times.

He remembers the first in 1999: "She called me within six hours of me doing the faecal transplant saying she didn't know what I did in there, but she felt better than she'd felt for six months and in fact she never had recurrence of that C. difficile."

As well as patients, he says there are more doctors expressing an interest in the US.

"Within the next six months or year, this will be the most exciting thing that's happened to gastroenterology. It will change the way that certainly C. difficile is treated and many other diseases too."

Irritable bowel syndrome, diarrhoea and constipation are also on his list of possible applications. "It looks like a terrific approach to a wide variety of diseases," he says.

Proof?

The practice has been reported only as a series of small case by case studies for recurrent C. difficile infection.

There has been an average success rate about 90%, external. However, this is not enough for the technique to be widely adopted.

The gold standard for determining if a treatment works is a randomised clinical trial - taking a large group of patients and giving one set the therapy and another a placebo or pretend therapy. The two groups are compared to see if the treatment really makes a difference.

Until such a trial takes place, widespread acceptance will be difficult achieve.

- Published21 March 2011