Black Death genetic code 'built'

- Published

The ancient burial site is under what is now the Royal Mint

The genetic code of the germ that caused the Black Death has been reconstructed by scientists for the first time.

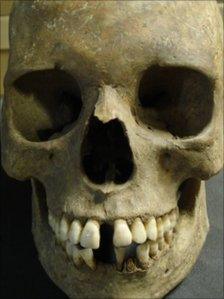

The researchers extracted DNA fragments of the ancient bacterium from the teeth of medieval corpses found in London.

They say the pathogen is the ancestor of all modern plagues.

The research, published in the journal Nature, external, suggests the 14th Century outbreak was also the first plague pandemic in history.

Humans have rarely encountered an enemy as devastating as the bacterium, Yersinia pestis. Between 1347 and 1351 it sparked the Black Death, an infection carried by fleas that spread rapidly across Europe killing around 50 million people.

Now scientists have uncovered some of the genetic secrets of the plague, thanks to DNA fragments drilled from the teeth of victims buried in a graveyard in London's East Smithfield.

Professor Johannes Krause from the University of Tubingen, Germany, was a member of the research team. He said all current strains circulating in the world are directly related to the medieval bacterium.

"It turns out that this ancient Yersinia pestis strain is very close to the common ancestor of all modern strains that can infect humans," he said.

"It's the grandmother of all plague that's around today."

Previously researchers had assumed the Black Death was another in a long line of plague outbreaks dating back to ancient Greece and Rome.

The Justinian Plague that broke out in the 6th Century was estimated to have killed 100 million people. But the new research indicates that plagues like the Justinian weren't caused by the same agent as the medieval epidemic.

"It suggests they were either caused by a Yersinia pestis strain that is completely extinct and it didn't leave any descendants which are still around today or it was caused by a different pathogen that we have no information about yet," said Professor Krause.

Tooth power

Globally the infection still kills 2,000 people a year. But it presents much less of a threat now than in the 14th Century.

DNA fragments were extracted from teeth

According to another member of the research team, Dr Hendrik Poinar, a combination of factors enhanced the virulence of the medieval outbreak.

"We are looking at many different factors that affected this pandemic, the virulence of the pathogen, co-circulating pathogens, and the climate which we know was beginning to dip - it got very cold very wet very quickly - this constellation resulted in the ultimate Black Death."

Rebuilding the genetic code of the bacterium from DNA fragments was not easy, say the scientists.

They removed teeth from skeletons found in an ancient graveyard in London located under what is now the Royal Mint.

Dr Kirsten Bos from McMaster University explained how the process worked.

"If you actually crack open an ancient tooth you see this dark black powdery material and that's very likely to be dried up blood and other biological tissues.

"So what I did was I opened the tooth and opened the pulp chamber and with a drill bit made one pass through and I took out only about 30 milligrams of material, a very very small amount and that's the material I used to do the DNA work."

From the dental pulp the researchers were able to purify and enrich the pathogen's DNA, and exclude material from human and fungal sources.

The researchers believe the techniques they have developed in this work can be used to study the genomes of many other ancient pathogens.

- Published1 April 2011