Gene therapy used in a bid to save a man's sight

- Published

Jonathan Wyatt: Hoping doctors can save his sight so he can continue to work as a lawyer

Researchers in Oxford have treated a man with an advanced gene therapy technique to prevent him from losing his sight.

It is the first time that anyone has tried to correct a genetic defect in the light-sensing cells that line the back of the eye.

The president of the Academy of Medical Sciences said the widespread use of gene therapy of this treatment will be soon be possible.

The operation was carried out on 63-year-old Jonathan Wyatt, an arbitration lawyer based in Bristol.

Mr Wyatt was able to see normally until about the age of 19 when he began having problems seeing in the dark.

He was told by doctors that his vision would get progressively worse and he would eventually go blind.

The gradual deterioration in his vision didn't stop Mr Wyatt from qualifying as a barrister. But 10 years ago he found he was having difficulty reading statements in dimly-lit courts.

"The worst occasion was when I was reading out a statement to the court and I made a mistake. The judge turned to me and snapped 'Can't you read Mr Wyatt?!' I then decided it was time to put my wig down and leave advocacy."

Geneticist Dan Lipinski, from the University of Oxford, explains the gene therapy process

Mr Wyatt is able to see well enough to work from home and hopes that the operation will enable him to continue his profession.

Without treatment he would be blind within a few years and would be unable to work in the way that he is doing so now.

"I'd like things to get a little better," he says.

Devastating diagnosis

Mr Wyatt suffers from a rare genetic disorder known as Choroideraemia.

These patients start off life with normal vision and its not until their late childhood that they notice that they cannot see anything at night and usually the diagnosis is made during middle to late childhood.

From then it is a devastating diagnosis because these young people are told that they are gradually going to lose their sight completely, usually by the time they are in their 40s. There is no treatment for this condition.

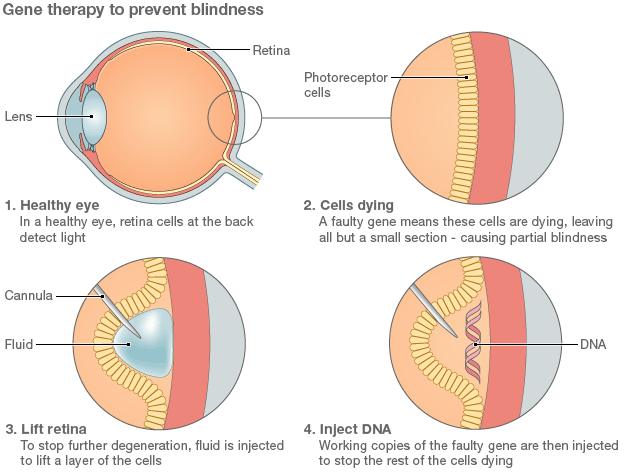

The disease is caused by an inherited faulty gene, called REP1. Without a functioning copy of the gene, the light detecting cells in the eye die.

The idea behind the gene therapy is simple: stop the cells from dying by injecting working copies of the gene into them.

It is the first time that anyone has attempted to correct a gene defect in the light-sensing cells that line the back of the eye.

Mr Wyatt is the first of 12 patients undergoing this experimental technique over the next two years at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford.

His doctor, Prof Robert MacLaren, believes that he'll know for sure whether the degeneration in Mr Wyatt's eye has stopped within two years. If that's the case his vision will be saved indefinitely.

"If this works with then we would want to go in and treat patients at a much earlier stage in childhood, effectively where they still have normal vision and can do normal things to prevent them from losing sight.

Prof MacLaren believes that if this gene therapy works it could be used to treat a wide variety of eye disorders, including the most common form of blindness in the elderly, macular degeneration.

"That is a genetic disease and I have no personal doubt in future that there will be a genetic treatment for it," he says.

The Oxford research follows on from a gene therapy trial which began four years ago at Moorfields Hospital in London. The principle aim of these trials was to demonstrate that the technique was safe.

The treatment, which adopted a slightly different approach, was tested first in adult patients whose sight was almost gone, and then in children.

According to Prof Robin Ali, who led that research, the trials have shown not only that gene therapy is safe - but that there has been significant improvement in some patients.

"It is very exciting to see the start of another ocular gene therapy trial and the field moving so rapidly in recent years," he said.

"In the last 12 months, several new gene therapy trials for the treatment of various retinal disorders have been initiated and further trials are likely to start very soon. We are all looking forward to seeing the results."

Hype

The concept of using gene therapy for treating a whole host of conditions has been around for more than 20 years. But with, some notable exceptions, it's an idea that's failed to live up to its hype.

Now, however, it seems that the technique is beginning to deliver, at least in treating sight disorders.

According to Prof Sir John Bell, president of the Academy of Medical Sciences, these very early trails in Oxford, London and in the US suggest that a whole host of sight disorders could, be treatable "within the next 10 years".

"Of all the things that are available for this particular set of diseases this is by far the most exciting," he said.

"This is a set of diseases where molecular medicine has reached a point where we can now intervene in a very precise way to correct the defect that caused the blindness in the first place. There is the possibility that you could actually correct the gene defect."

The trial, led by Oxford University, has been jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and Department of Health. It is an example of a new approach to medical research which brings together scientists and clinicians to translate basic science into effective treatments more quickly

"This is exactly where the NHS ought to be putting its effort and it's a perfect example of the benefits that might from using the NHS for this kind of research activity," said Prof Bell.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external