New hope for patients unable to communicate

- Published

- comments

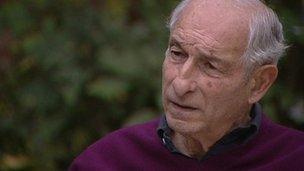

Roy Hayim could communicate only by moving his thumb

The thought of being trapped in a lifeless body, unable to communicate, is a terrifying prospect. It happened to Roy Hayim, a surveyor, who became dangerously ill after eating an airline meal.

Mr Hayim contracted botulism,, external a rare bacterial infection.

He was left paralysed and blind for several days, although he could hear everything that was happening - even a news report on the radio which said he was fighting for his life.

After about 10 days Mr Hayim was able to move his thumb and for the next eight months he used this method to communicate with his wife Caroline and hospital staff.

He spent nearly a year in hospital but made a full recovery. This all happened 20 years ago, but Roy remembers it vividly.

Awareness

"I felt trapped, afraid and terribly concerned. I didn't know whether I would survive or not," he said.

I went to meet Mr Hayim to get his insight on what it is like to be unable to communicate. My visit was prompted by research in the Lancet , externalwhich shows that electroencephalography - EEG - can be used to communicate with some patients who were diagnosed as vegetative.

Awareness was detected in three of the 16 patients.

Close your eyes and imagine wiggling your toes...

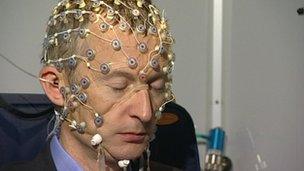

I was curious how EEG could be used to "read" thoughts so volunteered to test out the system in Cambridge at the Medical Research Council brain imaging centre.

The EEG had 129 electrodes and fits over the head a bit like an elasticated hair-net. From the photo you can see it is not a great look, but it is painless.

I was asked to wiggle my toes or squeeze my right hand when I heard a beep. Then I was asked simply to imagine doing the same tasks.

Thinking about doing something activates the same part of the brain - the pre-motor cortex - as doing it.

It is pretty hard to concentrate when you are simply thinking about wiggling your toes. All sorts of extraneous thoughts kept popping into my head.

Nonetheless I turned out to be an "excellent responder", according to Professor Adrian Owen, who has pioneered the use of scanning and EEG to try to communicate with brain-injured patients.

Three of the 12 healthy volunteers used in this study were unable to produce responses that were above chance - giving no concrete indication of a conscious response. Some of the vegetative patients, however, did considerably better.

Clearly the volunteers were aware and conscious. Prof Owen said it showed that a negative result did not mean that vegetative patients were definitely unaware, but a positive result did mean they had awareness.

Prof Owen has already shown that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used to communicate with a small proportion of vegetative patients.

EEG is cheaper and portable, so could be taken to the bedside of patients in care homes. It has been estimated that around four in 10 patients diagnosed as vegetative have some level of awareness.

Subject to further testing, this new technique might provide a rapid means of detecting awareness in a minority of patients who may have been trapped in an isolated world for years - aware but unable to communicate.

The research raises a multitude of questions - if patients can respond, what level of cognition do they have? Could it be used to help plan their treatment?

Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics, said: "This important scientific study raises more ethical questions than it answers. People who are deeply unconscious don't suffer.

"But are these patients suffering? How bad is their life? Do they want to continue in that state? If they could express a desire, should it be respected?

"The important ethical question is not: are they conscious? It is: in what way are they conscious? Ethically, we need answers to that."