How war has driven medical advances

- Published

Michael Mosley visits the hospital at Camp Bastion - the main base for British Forces in Afghanistan

Many key developments in healthcare have their origins in the battlefield where the treatment of injured troops has led to innovations throughout history which continue today.

The hospital at Camp Bastion in Afghanistan is at the forefront in developments in trauma surgery. Last year it handled 8,000 casualties, many of them with extremely serious injuries.

Incredibly, US and British army medics now expect to save 90% of those patients, the highest figure in the history of warfare.

Yet 500 years ago, the best a fallen soldier could hope for was to be dragged off the battlefield by his friends and, if he survived long enough, have his wounds cauterised with hot irons or sealed with boiling oil.

Horrors of war

Blood loss has always been the biggest killer in war. A big turning point came, in 1537, when a French barber called Ambroise Pare was sent as a surgeon to the Siege of Turin.

He was so horrified by what he saw, that he came up with an incredibly simple alternative, the ligature. He would identify bleeding arteries, clamp them, and then tie the ends with silk threads.

Ligatures were used by the Romans and the Arabs, but the skills had been lost and it took time for Pare's work to change people's attitudes. A century later surgeons were still using boiling oil and cauterising wounds.

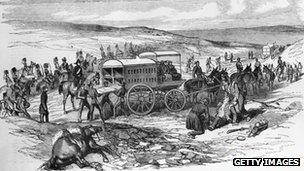

The idea of using specialised transport to evacuate the wounded from the battlefield came 200 years ago and again it was a Frenchman who first saw the need.

Dominique Jean Larrey, surgeon-in-chief to Napoleon's armies, noticed that the French artillery were able to move cannon at high speed around the battlefield with horse-drawn carriages.

He wondered if similar vehicles could be used to move casualties. At the time many soldiers were left to die where they fell. It could take 24 hours or more to get a wounded man to a field hospital.

"When a limb is carried away by a ball, by the burst of a grenade, or a bomb, the most prompt amputation is necessary," Larrey wrote in his memoirs.

"The least delay endangers the life of the wounded.... without the assistance of the flying ambulance...a great number would have died from this cause alone."

Larrey created what he called, "flying ambulances". These were horse-drawn carts which could carry the wounded in some comfort and at high speed to the waiting surgeons. The Duke of Wellington was so impressed he ordered his men not to fire at them.

Air ambulance

In Afghanistan, modern equipment has allowed Larrey's approach to be taken to a new level with troops evacuated by a helicopter carrying a doctor, nurse and two paramedics, as well as the sort of equipment you would normally find in a hospital emergency unit.

A Crimean War ambulance was drawn by six mules and had room for 10 patients - four on stretchers

But the treatment starts while the air ambulance is still scrambling into action.

American and British troops are now all equipped with tourniquets, so if a colleague loses an arm or leg they can apply pressure to stop the bleeding, long enough to get them onto the helicopters and heading for hospital.

En route they are given blood, often a lot of it. Army medics working in Iraq discovered that if troops were given extra plasma, which contains agents that help blood clot, this almost doubled survival rates.

On arrival at Camp Bastion, casualties are scanned for signs of internal bleeding, in which case surgery can be under way in minutes with teams of doctors working on a single patient.

"Without a doubt people have gone back alive who 5 years ago would not have survived," said Lieutenant Colonel Steve Lord, a consultant in the Emergency Department at Camp Bastion.

Anyone with a suspected internal injury gets a full body scan he explained. "That is something we should consider more of in the NHS."

The new blood protocol, with increased plasma for trauma patients is already being introduced in parts of the NHS.

And the military tourniquets, which can be applied with one hand, are also being used by increasing numbers of ambulance services.

Another technique developed by the military, hand in hand with civilian medics is the use of portable ultrasound.

This is used not only for scans but also for pain control by allowing surgeons to locate and anaesthetise individual nerves.

Ultrasound was itself a product of war, first used by tank engineers in World War Two to detect cracks in armour.

Today it has become a fantastic medical tool, used for everything from scanning pregnant women to looking for cancers.

- Published18 November 2011