Is HIV still a death sentence in the West?

- Published

Drugs that suppress HIV have cut Aids deaths dramatically in the rich world

For many in the affluent world, HIV has become yesterday's epidemic. A quarter of a century of drug development means that for most people who contract the virus it has become manageable through medication. Yet Aids still claims many lives in the West.

In a quiet road, a short walk from the bustle of the High Street in St Albans, Hertfordshire, is an HIV support group called The Crescent.

Two of its regulars, Mike and Fiona (not their real names), have come together to share their experiences of living with HIV on either side of the anti-retroviral revolution.

Mike, who was diagnosed with HIV in the late 1980s, aged 26, remembers being part of a support group in which many fellow members died. He recalls the black humour of the time.

"It became like a standing joke. Who's the next one that's going to drop like flies, because people were."

For Mike, it was almost him. He had a brush with death after returning from a trip to the US.

"When I came back I was chronically ill. I fell asleep and I woke up two days later and my niece had been ringing the house, she'd been expecting me home two days before and over to hers.

"Fortunately one of my neighbours have got a spare key and she came in. I was in bed and I looked like I had fallen out of bucket. Apparently I was in a real bad state.

"If I'd stayed there on my own I probably wouldn't have been here now."

By contrast, when Fiona's daughter was diagnosed, in 2001, drugs that suppress HIV were widespread in the UK. Yet she too fell very ill, repeatedly getting pneumonia after giving birth.

Fiona remembers one particularly bad episode.

"She was sick, she was very, very thin. She couldn't breathe. She was blue round her mouth. Her eyes were black. At one stage I thought that was it, she was going to go."

The point is clear. While people with HIV in developed countries have come to rely on drugs that help suppress a virus that was once a death sentence - both know that, even in the rich world, HIV can still be a killer.

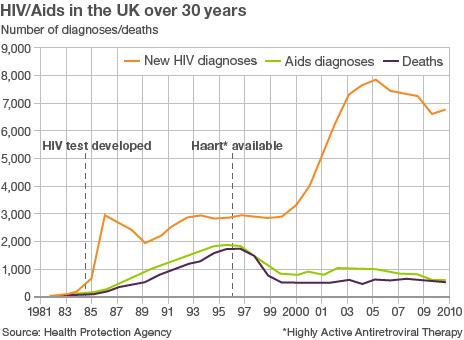

In the UK, 680 people with HIV died last year, according to the Health Protection Agency. , externalThat's a long way down from the 1995 peak of 1,723 deaths, but still a significant number.

At the end of 2009, total deaths of people with an Aids diagnosis in the UK, numbered 15,180. That's lower than many other major European countries, such as Spain (44,883), Italy (36,210) and France (35,600), and close to Germany's figure of 14,065.

An expert for the Terrence Higgins Trust, which campaigns on Aids and HIV issues in the UK, says the difference can be explained by the fact the UK and Germany were more proactive in launching effective public health education schemes, and clean needle exchange initiatives.

But even then, the ready supply of anti-retroviral drugs to patients has not wiped out Aids deaths in the West.

Indeed, for charities such as Community Servings, based in the Jamaica Plain area of Boston, and The Food Chain, in London, Aids remains a killer. They provide nutritious meals to individuals and families living with HIV/Aids.

Riding along with Christopher Muhammad who delivers meals to people with HIV/Aids

Every Sunday morning volunteers at The Food Chain make their way to one of four kitchens where they prepare meals before delivering them to homes around the UK capital.

General manager Andrew Davies says: "A lot of these people are just out of hospital, they don't have any support."

"Many of the users that we support have quite complex health needs, not just HIV-positive, but might also have diabetes or TB co-infection renal problems all sorts of things."

16 years more

Results of a study released last month, showed life expectancy of those with HIV who are on anti-retroviral treatment, has improved. In 1996, when such drugs were starting to become widespread, the UK Medical Research Council estimated a 20-year-old with HIV, who was receiving treatment, could expect to live to an average age of 50.

By 2008, this group could expect to live to an average age of almost 66 - a 16-year improvement.

There are wide variations. Many of those who die from Aids-related illnesses, do so younger, often because they were not diagnosed early. Mike, of the St Albans support group, says he doesn't expect to live beyond 60.

Nevertheless, the curve in life expectancy for people with HIV appears to be going up. One doctor believesmany HIV patients can expect a normal lifespan in years to come.

Kaposi's sarcoma, a type of cancer, is one of the most common opportunistic infections in people with Aids

"If a person is diagnosed with HIV today, the first thing I would say to them is I expect to see them for the next 30 years plus and that is because the treatment is so good," says Dr Steve Taylor, an HIV specialist at Birmingham Heartland Hospital.

"If they can get that medication then their life expectancy after you've been on the drug for five years is that of the general population."

However, one in four HIV-positive people have not been diagnosed and half of those being diagnosed are diagnosed "late". Those classified as "late" have a severely reduced immune system.

For them, as the immune system gets weaker still, the body becomes vulnerable to opportunistic infections and some tumours, which land the fatal blow.

"Until we actually tackle the problem of diagnosing the undiagnosed then that [death] rate is going to continue," argues Dr Taylor.

"So the more people we diagnose the more people we can get onto therapy early enough, that's when the rate will start to fall."

Until then, HIV may no longer be the automatic death sentence that it was two decades ago, but it is still deadly. That is just in the West, however, in many parts of the world access to lifesaving treatments remain woefully poor.