How France and UK differ on implants

- Published

- comments

France and Britain are taking different stances over the safety of the banned PIP implants

There will be many women left confused and worried about latest developments over French breast implants.

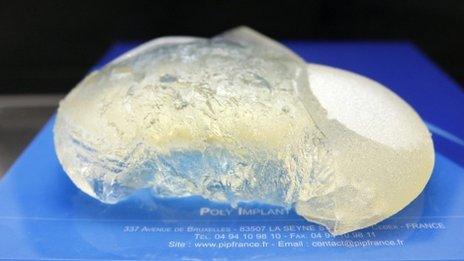

The implants by French firm Poly Implant Prothese (PIP) were banned last year when it emerged the company had used a non-medical grade silicone filler.

There is now a clear division between the French and British health departments over what women with the PIP implants should do.

The French government is recommending and will pay for the removal of the banned implants, and will cover the cost of their replacement if the original treatment was for breast reconstruction following cancer.

Rupture risk

So why is it taking this action? French health minister Xavier Bertrand said the removal was "preventive and not urgent".

No increased risk of cancer has been found compared to other implants but he pointed to the "well-known risk of rupture" and the irritative power of the gel filler which could lead to an inflammatory reaction.

If women decide not to have the implants removed, the French government says they should have free six-monthly ultrasound scans.

This move is a direct result of the findings of an expert group, external at the National Cancer Institute in France which was asked on 5 December to examine the evidence surrounding the PIP implants.

Cancer

The expert group did find an increased risk of one extremely rare cancer - anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) from all breast implants.

This is not a new finding, and the committee don't go into any detail. Rather, it is in line with a detailed investigation by the US Food and Drug and Administration (FDA).

Concern over the PIP implants in France was renewed last month following the death of a woman from lymphatic cancer.

The French committee did not find any increased risk of ALCL from the PIP product compared to other implants.

The expert group found no additional risk of breast cancer from implants in general or PIP in particular.

Nor did it have any new data regarding the unauthorised silicone filler, which was meant for products like mattresses, according to the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS).

But it was concerned about what it called the "potential toxicity of the gel" as an irritant.

In France the rupture rate is said to be 5% and once this has happened it is more difficult to remove.

But the approach here is quite different. The Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Authority, external has carried out its own investigation and said the rupture rate of the PIP implants is 1% - other countries have similar rates to the UK.

Monitoring

It is impossible, at this stage, to explain how there could be such a difference in rupture rates in France and other countries. Some have suggested that the French are monitoring the implants more thoroughly and scanning women more frequently, but I can't get any figures on this.

Health Secretary Andrew Lansley said removing the implants was not without danger: "It requires an operation, requires anaesthesia, requires a degree of risk. So from our point of view, we're not in a position to recommend a risk should be entered into routinely where there is no safety concern that would justify taking that risk."

But some surgeons believe women here should be offered the choice of removal.

Nigel Mercer, former BAAPS president said: "The industrial-grade silicone gel used in these implants was not meant for the human body. In some instances women who have no rupture of the devices will be happy to be monitored regularly, but others may wish for the PIPs to be removed, regardless of symptoms. The French government's stance is certainly not unreasonable."

Women in the UK are being advised to talk to the surgeon who fitted their implant.

Many will undoubtedly point to the stark difference between the British and French positions.

Ninety-five per cent of the implants were fitted by private clinics, the vast majority of these procedures will have been for breast augmentation.

The NHS will step in only if an implant is leaking or if there is clear clinical need. So, at present, it looks as though women who want to follow the French precautionary approach will have to pay for the surgery themselves.

- Published23 December 2011