'I was treated by the pioneers of insulin in 1930'

- Published

Frederick Banting discovered insulin by keeping a diabetic dog alive with pancreas extract

Insulin has saved the lives of countless people with Type 1 diabetes.

In 1921, when the hormone was first discovered by a young Canadian surgeon named Frederick Banting, most children diagnosed with diabetes were expected to die within a year.

Ninety years on and Banting's breakthrough is being hailed a one of the twentieth century's most important medical advances.

Insulin in all its forms continues to ease and prolong the lives of diabetics by keeping blood glucose levels under control.

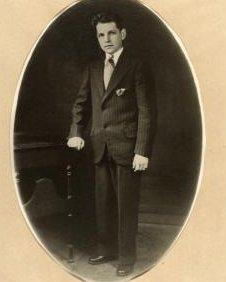

Sheila Thorn was lucky enough to be treated by Banting in Toronto in 1930 when she was diagnosed as diabetic at just a few months old.

The insulin he prescribed for Sheila has kept her alive for 80 years, making her probably the longest surviving insulin-dependent diabetic in the world.

Lucky

"I've got a picture of me in mother's arms when we were in Canada. When I was a baby, insulin still wasn't widely available.

"I was lucky enough to be treated by the pioneers of insulin and that's why I'm still here."

Now living in East Sussex, Sheila remembers being on a very strict diet growing up and her mother injecting her two or three times a day.

"Since then, I've seen a lot of changes in the way people use insulin and these days I use an insulin pump to control my own condition. It makes a world of difference."

Millions of people like Sheila have used various types of synthetically produced insulin to replace the natural insulin that is not produced in people with Type 1 diabetes.

In Toronto in 1921, a severely diabetic dog was the key to Banting's discovery.

Leonard Thompson was the first patient to receive insulin in 1922

Assisted by Charles Best, he kept the dog alive for 70 days by injecting it with a canine pancreas extract.

'Life-saving drug'

The first human to benefit from the extract was a 14-year-old boy called Leonard Thompson, who was dying of starvation with diabetes.

Within days his dangerously high blood sugar levels had dropped to near normal levels, and his life was saved.

News of the miracle extract, insulin, spread and soon scientists had clear evidence that it was a life-saving drug.

How insulin can be administered and managed has changed dramatically over the years.

Blood tests, insulin pumps and the many kinds of human and animal insulin now available make it easier to control how much is required by an individual diabetic.

Karen Addington, chief executive of medical research charity, JDRF, says it is still a fine balance.

"Before I got an insulin pump, I had to take a precise dose of insulin and calculate the carbs I was eating and also things like exercise and stress, which can also have an impact. I was always juggling things around."

With an insulin pump delivering a varied dose of insulin continually throughout the day and night, Karen says it mimics the working of the pancreas in someone who does not have diabetes.

But it still doesn't test blood glucose levels or work out how much insulin to deliver.

'Mechanical cure'

The future promises two ways of getting round these problems, which could revolutionise life for diabetics.

The first is an 'artificial pancreas', essentially an insulin pump linked to a blood sugar monitor which is worn externally and is the size of a thumbnail.

"It will mean no hypos and hypers and no complications for people with Type 1 like strokes, amputations or blindness.

"It's a mechanical cure."

The second product being invested in by JDRF is a type of insulin which reacts to levels of glucose in the body, releasing insulin into the blood whenever it is needed.

"The pace of development in Type 1 diabetes is really amazing," says Addington, who hopes that trials of both devices will lead to general use in a few years or so.

But Barbara Young, from Diabetes UK, still believes more should and could be done to manage both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

"Diabetes is seen as a less serious disease than cancers and strokes, but you can die from it too.

"Perhaps because it's a long-term condition, there's a lack of political will to properly manage and educate patients so that complications and hospital admissions are avoided."

Young cites the example of insulin pumps, which only 3.9% of people with Type 1 diabetes have access to in the UK because of "a postcode lottery and a lack of funding".

'I would have died'

Amy Turner, who is 28, knows what it is like to have Type 1 diabetes but no pump to help her, especially since she is a keen runner.

"It is not easy but I have to adapt and plan ahead. I never go out without a bag full of extra sugar if I need it.

"I am sadly not eligible for an insulin pump, although the doctors can see how it would benefit me."

Yet, Amy is determined that her diabetes will not get in the way of her life.

"I would have died it it hadn't been for insulin. With the different types of insulin now, I can do what I want to do. I want to prove I can do physical things like half marathons."

Frederick Banting would be proud. But Amy has the final word.

"Insulin is a life-saver, but it's not a cure, just a treatment."