Malaria deaths hugely underestimated - Lancet study

- Published

Mosquitoes carry the parasite which causes malaria in humans

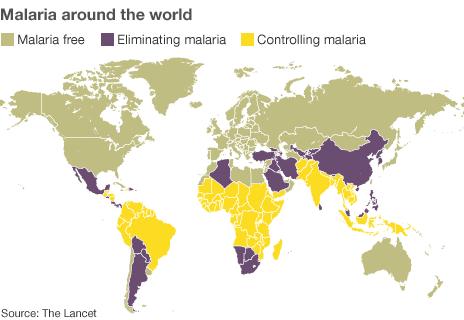

Worldwide malaria deaths may be almost twice as high as previously estimated, a study reports.

The research, published in the British medical journal the Lancet, external, suggests 1.24 million people died from the mosquito-borne disease in 2010.

This compares to a World Health Organisation (WHO) estimate for 2010 of 655,000 deaths.

But both the new study and the WHO indicate global death rates are now falling.

The research was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It used new data and new computer modelling to build a historical database for malaria between 1980 and 2010.

The conclusion was that worldwide deaths had risen from 995,000 in 1980 to a peak of 1.82 million in 2004, before falling to 1.24 million in 2010.

The rise in malaria deaths up to 2004 is attributed to a growth in populations at risk of malaria, while the decline since 2004 is attributed to "a rapid scaling up of malaria control in Africa", supported by international donors.

While most deaths were among young children and in Africa, the researchers noted a higher proportion of deaths among older children and adults than previously estimated. In total, 433,000 more deaths occurred among children over five and adults in 2010 than in the WHO estimate.

A lab technician analyses a blood sample to check for malaria in a hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone

"You learn in medical school that people exposed to malaria as children develop immunity and rarely die from malaria as adults," said Dr Christopher Murray of the University of Washington in Seattle, who led the study.

"What we have found in hospital records, death records, surveys and other sources shows that just is not the case."

The researchers also concluded malaria eradication was not a possibility in the short-term.

"We estimated that if decreases from the peak year of 2004 continue, malaria mortality will decrease to less than 100,000 deaths only after 2020," they write.

Disturbing numbers

The Lancet's editor, Richard Horton, told the BBC: "Right now we don't actually have any reliable primary numbers for malaria deaths in some of the most malarious regions of the world, so what numbers we have come from estimates.

"What this paper reports is a new way of estimating the number of malaria deaths, where they've used additional data sets and improved mathematical models from calculating mortality."

But despite what he calls the "disturbing" number of deaths recorded, he believes the underlying message of the report is that the disease can and is being controlled.

"Since 2004, the number of malaria deaths has dropped by about a third, and that's really been the time when the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria has swung into action" he said.

"Over the past decade, 230 million cases of malaria have been treated and the same number of bed nets have been distributed to people at risk of malaria, and the result of that has been this huge downturn. So what we know is that we're actually able to turn off malaria with our existing interventions."

Commenting on the new study, Professor David Schellenberg of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said the researchers had "gone to great lengths to assemble information from a range of sources and to make adjustments for the inadequate data quality".

"We can argue about the strengths and weaknesses of their approach but should not be distracted by the details of the methods: however you look at it, far too many people are dying from malaria.

"The introduction of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria, recommended by the WHO in 2010 and increasingly available in endemic countries, affords an unprecedented opportunity to take the guesswork out of malaria diagnosis and to improve the reliability of information," he added.

The new survey involved a range of measures to try and obtain a better estimate of global malaria deaths. New data sets were examined and computer models built which factored in a host of elements such as transmission rates, healthcare access, drug resistance and bednet coverage.

The work also involved trying to judge the impact of the misclassification of deaths in the affected regions. This readjustment alone generated a rise of 21% in the number of malaria deaths.

- Published29 October 2010

- Published21 April 2011