How significant are developments in making Alzheimer's brain cells in the lab?

- Published

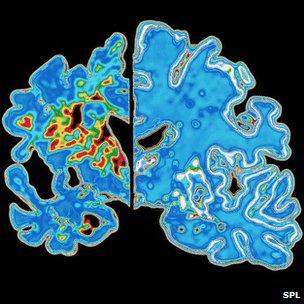

Alzheimer's brain of the left showing brain shrinkage, health brain on the right

Dementia has been described as a "time bomb" in society. As more people are living longer, more are being affected by the illness which slowly but surely annihilates brain function.

More than 750,000 people in the UK already have dementia, forecasts say there will be one million dementia patients by 2021 and 1.5 million by 2051. The cost to health services and the economy is already put at more than £20bn each year.

However, the scale of the problem is in stark contrast to the level of understanding. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia, yet the cause is unknown and there is no cure.

When it comes to studying dementia you cannot simply take samples of brain tissue from patients to understand what is going on or to test treatments. Research requires good "models" of the disease instead, something many scientists would argue are not good enough.

It is why some are hopeful that developments in the laboratory will help make a breakthrough.

In the past few months, research groups have reported significant advances in creating Alzheimer's cells which can be grown, in a dish, in a lab.

Last month, a group of US scientists used stem cell technology to make Alzheimer's brain cells, external both from patients at high risk of the disease and from those who with no family history of the condition.

They took skin cells from patients and converted them into stem cells, which are able to become any other type of cell in the body. These cells were then transformed into neurons which can be studied in the lab.

Lead researcher Prof Lawrence Goldstein, from the San Diego School of Medicine at the University of California, said at the time: "Creating highly purified and functional human Alzheimer's neurons in a dish - this has never been done before."

A similar approach was used, external by Dr Rick Livesey's team at the University of Cambridge. They used skin from patients with Down's syndrome, who are more likely to develop Alzheimer's.

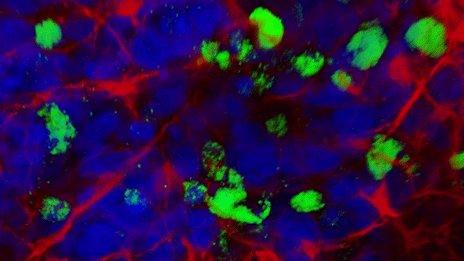

Neurons in red and blue, destructive brain plaques forming in green, Picture: Yichen Shi, Livesey lab, University of Cambridge

He said is was possible to now see the "whole process of the disease" unfurl in a dish in a laboratory.

Model behaviour

Prof Goldstein said the current models were not good enough: "Researchers have had to work around, mimicking some aspects of the disease in non-neuronal human cells or using limited animal models.

"Neither approach is really satisfactory."

Huge swathes of research is done on "Alzheimer's mice", such as a development last week on rapidly clearing dementia plaques from the brain.

This is hugely valuable research, however, there are limitations. No animals, apart from humans, get Alzheimer's disease. Inserting the right genetic material into mice can simulate the early symptoms, yet, it is still not Alzheimer's.

Drugs which appear to work in mice often fail to make the leap into being successful human treatments - there are big differences in both the size and complexity of the brains of mice and men.

The idea is that doing experiments on human brain cells, which will develop Alzheimer's, will provide another avenue of research.

Dr Rick Livesey said his cells in the lab formed destructive ameloid plaques and eventually died, two key characteristics of Alzheimer's, when grown in a laboratory.

"What it allows us to do is study the disease progression in real time allowing us to test possible drug treatments. It accelerates the whole process," he said.

Prof Goldstein told the BBC his lab were already using the cells for "understanding mechanisms of disease development, testing drugs and probing the role of genetic variation in disease development".

Dr Simon Ridley, head of research at Alzheimer's Research UK, said progress had been "hampered by lack of a really good model" and that drug development had been "dogged by failure".

"Post mortem tissue has probably contributed more than anything else to understanding Alzheimer's," he said.

However, he cautioned that stem cell models were "not a panacea" as they cannot demonstrate brain function. Whereas "Alzheimer's mice" can perform memory and cognitive function tests.

Alzheimer's stem cells will be a "very useful and important tool in the armoury," he said.

- Published9 February 2012

- Published10 December 2010

- Published29 December 2011

- Published4 April 2011

- Published28 November 2011