How India has had remarkable success in polio fight

- Published

Fergus Walsh visits a polio immunisation clinic in Delhi

One by one the young children open their mouths to receive the two drops of polio vaccine. Then they hold out their hand to get their "purple pinky" - one finger painted with indelible purple ink to show they've been immunised.

Some of the children try, and fail, to suck off the ink because they want to get another toy - some stickers, a balloon or pencil - as a reward for coming to the booth.

There are 7,000 impromptu vaccination booths across the capital. Across India, these regular National Immunisation Days aim to reach more than 170 million children under five - the group most at risk from polio. I'm here to witness India's successful fight against polio.

Several of the booths in Delhi are staffed by volunteers from Britain; they are all members of Rotary - the worldwide network of clubs of business and community volunteers.

The Rotary volunteers - wearing bright yellow shirts - attract a lot of attention. Veronica Stabbins, from Windsor in Berkshire, is here with her husband Adrian - they immunise around 200 children in two hours.

Mohammad Zaid, left paralysed by polio as a baby, remains determined and hopeful about life

She said: "This is our third visit to India volunteering for Rotary. It is wonderful to be part of trying to eradicate this dreadful disease. When we go home we try to raise awareness of what still needs to be done."

Another Rotary member, Jenny Schwarz from Merseyside, said: "I've been raising money to fight polio for 25 years. My dream is to have a polio-free world."

All the Rotary volunteers - there are more than 40 of them from Britain, and 500 from around the world - pay all the expenses of their trip and then often use the experience to do further fund-raising at home.

Remarkable achievement

India used to be the epicentre of polio. In 1985, there were an estimated 150,000 cases in India and as recently as 2009 there were 741, more than any other country in the world.

But its last case was in January 2011 - a remarkable achievement. But it won't be officially removed from the list of polio endemic countries until the result of lab tests confirm that it is no longer to be found in sewage.

That confirmation is expected in the next few weeks. It will leave three endemic countries: Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria where the virus has never been under control. All saw an increase in cases last year.

The success in India has been achieved through a partnership between the Indian government, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary, Unicef and with major contributions from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Last year the UK government doubled its support to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI).

Dr Mathew Varghese described the stigma faced by children with polio

A visit to St Stephen's Hospital in Delhi offers a stark reminder why polio used to be one of the world's most feared diseases. Mohammad Zaid is 11 and he caught polio as a baby. The virus attacked the cells in his spinal cord, paralysing his legs which are now wasted.

He gets about by crawling, but is at the hospital for surgery. Mohammad will need four operations - to straighten each hip and knee - before he can be fitted with metal calipers so that he can finally walk.

Dr Mathew Varghese, head of orthopaedics, said children with polio don't just suffer physically: "Many of them drop out of school early and they face a stigma being disabled - and all this from a disease which can be prevented with a vaccine."

Polio history

Polio has been causing disability and death since ancient times.

There is an stone engraving from Egypt around 1400BC which shows a priest with a withered leg typical of paralytic polio.

Poliomyelitis has existed as long as human society, but became a major public health issue in late Victorian times with major epidemics in Europe and the United States. The disease, which causes spinal and respiratory paralysis, can kill and remains incurable but vaccines have assisted in its almost total eradication today.

This Egyptian stele (an upright stone carving) dating from 1403-1365BC shows a priest with a walking stick and foot, deformities characteristic of polio. The disease was given its first clinical description in 1789 by the British physician Michael Underwood, and recognised as a condition by Jakob Heine in 1840. The first modern epidemics were fuelled by the growth of cities after the industrial revolution.

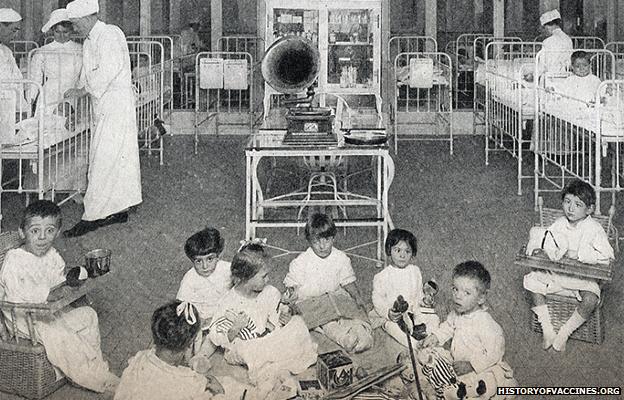

In 1916, New York experienced the first large epidemic, with more than 9,000 cases and 2,343 deaths. The 1916 toll nationwide was 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths. Children were particularly affected; the image shows child patients suffering from eye paralysis. Major outbreaks became more frequent during the century: in 1952, the US saw a record 57,628 cases.

In 1928, Philip Drinker and Louie Shaw developed the "iron lung" to save the lives of those left paralysed by polio and unable to breathe. Most patients would spend around two weeks in the device, but those left permanently paralysed faced a lifetime of confinement. By 1939, around 1,000 were in use in the US. Today, the iron lung is all but gone, made redundant by vaccinations and modern mechanical ventilators.

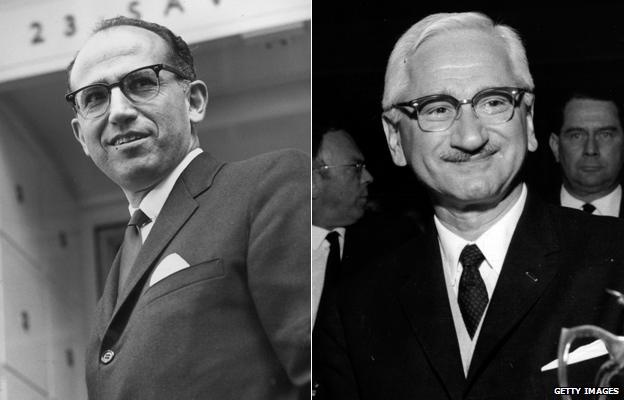

A major breakthrough came in 1952 when Dr Jonas Salk (L) began to develop the first effective vaccine against polio. Mass public vaccination programmes followed and had an immediate effect; in the US alone cases fell from 35,000 in 1953 to 5,300 in 1957. In 1961, Albert Sabin (R) pioneered the more easily administered oral polio vaccine (OPV).

Despite the availability of vaccines polio remained a threat, with 707 acute cases and 79 deaths in the UK as late as 1961. In 1962, Britain switched to Sabin's OPV vaccine, in line with most countries in the developed world. There have been no domestically acquired cases of the disease in the UK since 1982.

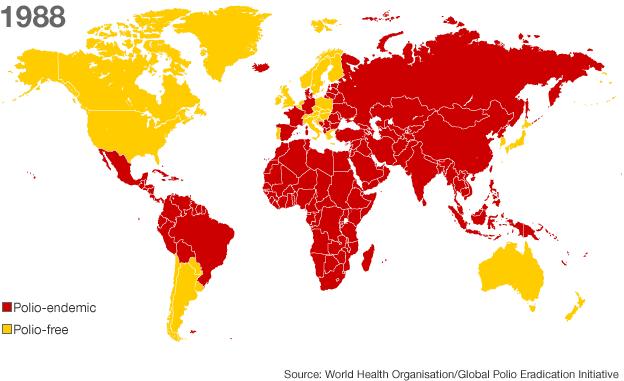

By 1988, polio had disappeared from the US, UK, Australia and much of Europe but remained prevalent in more than 125 countries. The same year, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to eradicate the disease completely by the year 2000.

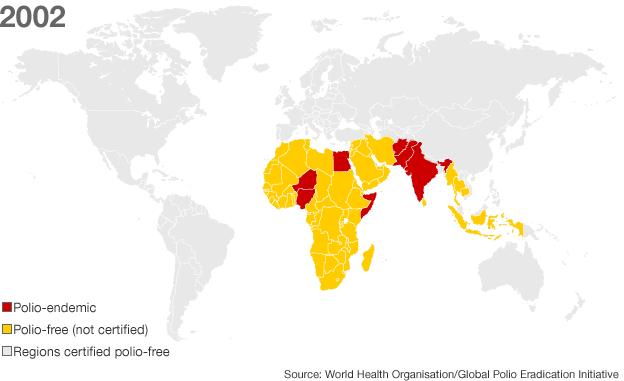

The WHO Americas region was certified polio free in 1994, with the last wild case recorded in the Western Pacific region (which includes China) in 1997. A further landmark came in 2002, when the WHO certified the European region polio-free.

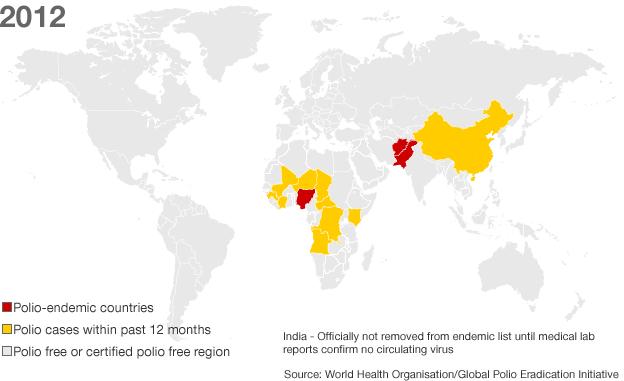

In 2012, Polio remains officially endemic in four countries - Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan and India, which is on the verge of being removed from the list having not had a case since January 2011. Despite so much progress, polio remains a risk with virus from Pakistan re-infecting China in 2011, which had been polio free for more than a decade.

When the virus was ubiquitous and entire populations were constantly being re-infected, the disease appears to have been comparatively rare.

Infants were infected at an early age when paralysis is less likely to occur.

Epidemics of polio were not recognised until the advent of improved sanitation and water supplies. This meant that there were sufficient numbers of people without immunity.

From the late 19th Century major outbreaks occurred in the summer months in the US and Europe.

The ability of the virus to cause crippling disability and death within hours meant polio became a greatly feared infection.

In the late 1920s the so-called iron lung was first used to help patients paralysed with polio to enable breathing.

The last per cent

There are two vaccines against polio. The first - an injected dose of inactivated (killed) virus - was developed by Dr Jonas Salk, and introduced in 1955.

A second, oral polio vaccine was created in 1961 by Dr Albert Sabin using a live attenuated (weakened) strain of virus.

It has been this vaccine, given in drops, which has been the main tool of polio eradication.

Mass immunisation campaigns led to a dramatic drop in polio cases.

Rotary International created the PolioPlus programme in 1985 aimed at eradicating the disease.

Its members, known as Rotarians, have raised $1bn (£630m) to support polio immunisation.

In 1988 the World Health Assembly set a target of eradicating polio by 2000. That year an estimated 350,000 people were paralysed or killed by polio and the virus was endemic in 125 countries.

The official number of cases of paralytic polio was 32,419 but the WHO said this grossly underestimated the real figure.

Since then the number of cases has been reduced by more than 99%, but it is the final 1% which may prove the toughest to deal with.

Persistent outbreaks

Last year there were 647 cases in 17 countries.

Nearly a third of those were in Pakistan.

Other countries with cases, such as Chad and DR Congo, have persistent outbreaks, but as a result of the virus being imported from one of the endemic countries.

Until polio is eradicated there will be the danger that the virus will be reintroduced to India, across the border from Pakistan.

Polio virus from Pakistan re-infected China in 2011, which had been polio free for more than a decade.

The polio virus cannot survive outside the human body for long periods and so if the virus is unable to find someone to infect it will die out.

Prof Nicholas Grassly, a vaccine epidemiologist at Imperial College London, said: "The major hurdles are now political. A key problem is that last year Pakistan abolished its federal ministry of health so there are concerns about disease surveillance, and organising vaccine programmes like polio."

In Afghanistan polio immunisation has been hampered by conflict and security concerns. And in Nigeria local opposition to polio immunisation was a problem in recent years.

The global effort to eradicate polio is the biggest public health initiative in history. It has cost billions and has already stopped a huge amount of disability and many deaths.

Dr Bruce Aylward, director of the GPEI, said there was a "historic opportunity" to eradicate polio but warned that failure could bring about a resurgence of the disease.

The world will need to be free of all cases of polio for three years before the disease could be declared eliminated.

The next few years will decide whether the programme ends in success or failure.

It will come too late for children like Mohammad Zaid in Delhi. But like all the polio patients I met he is determined not to be defined by his disability.

"When I leave here I am going to walk out of the hospital", he says with a smile. The hope must be the polio wards in India and throughout the world will one day treat their last patients.

- Published25 September 2015

- Published25 January 2012