Will 10-year-olds be popping pills to live longer?

- Published

Are we destined to rely on drugs and pills at an increasingly young age to help us survive longer?

Life expectancy has changed dramatically in a century.

In 1908, half the UK population was dead by 60 and in 1948, when the contributory state pension was introduced, half the population was dead by the age of 72.

Falling mortality rates, as a result of advances in science and medicine, mean the average UK man and woman can expect to live into their 80s, perhaps even to the age of 100, but what will the quality of our lives be like?

And will we have to resort to more and more drugs to keep us alive?

The longer we live, the more prone we are to chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke and cancer.

Drugs can help control and reduce the symptoms of these conditions and increase our longevity, but the danger is that we will come to rely on them too much.

Professor Sarah Harper, director of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing at Oxford University, believes that keeping more people alive for longer and longer will come at a cost.

"We have to ask if we wish our future to be one where individuals, at increasingly younger ages, pop pills rather than eat healthily, stop smoking, reduce alcohol and take up exercise.

"Do we want 10-year-olds popping statins?"

Her evidence for this isthe impact obesity has had on life expectancy in the United States.

There, about one in three adults is classified as obese, and life expectancy is not keeping pace with life expectancy in the UK and Australia, for example.

Recent research concluded that although obesity was on the rise in the 1990s and causing lost years of life, this trend had not continued during the last decade.

So while obesity has continued to increase, life expectancy has not reduced by the same amount because people are relying on drugs to manage the diseases which obesity causes.

"We must be wary of this," Prof Harper says.

"The population appear to be saying that 'I can eat as much as I like and take a pill to stop the effects.' It is very worrying."

But Professor Tom Kirkwood, associate dean for ageing from Newcastle University, is more optimistic about attitudes to growing and living old.

"People are likely to exhibit more chronic diseases as lifespan lengthens. However, part of the driver for increased longevity is that better management of chronic diseases is resulting in better maintenance of health and wellbeing."

Prof Kirkwood refers to a study of the medical, biological and psychosocial factors affecting the health of people aged 85 and over in Newcastle in 2009 which found that four our of five felt their health was "good", "very good" or "excellent".

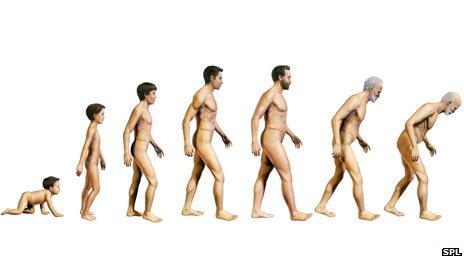

If life expectancy continues to rise, will the Seven Ages of Man stretch to eight or 10?

This was despite the fact that they typically had several health issues, and most had three to six chronic diseases.

"They may therefore be taking regular medication and receiving relevant check-ups but this is relatively inexpensive, well-managed and cost-effective," he says.

So although the healthcare needs of an ageing population will increase and the focus on chronic disease management will rise, it may not necessarily result in a poor quality of life.

Experts agree that keeping fit and healthy, and eating well, throughout our lives are the keys to living a long life.

ONS statistics show that a 65-year-old man retiring with ill health in 2010, who had a low income and an unhealthy lifestyle, could expect 11 more years of life.

Yet 65-year-old men who retired in good health on high incomes and a healthy lifestyle had a life expectancy of a further 23 years.

The burden of an ageing population is not in doubt, though.

A growing number of older adults combined with a declining number of younger people - as a result of falling fertility rates - means that the structure of the UK population is changing.

Like most countries in most regions of the world, people are living longer and not having as many children as before.

The "pyramid" shape so often used to show how a population is made up is becoming a "skyscraper" with fewer children and young people at the bottom.

Families are also getting smaller, the labour force is reducing in size and yet the growing number of elderly people have to be looked after and paid for.

"Elderly people need hands-on care in their homes. It's not something which can be automated or done by robots. Society has to adjust quickly to this," says Prof Harper.

When it comes to our personal life expectancy, it is dictated by our genes and our environment in a complicated formula which no one yet understands.

But there is agreement that our early lives - even in the womb - are very important in determining how long we live.

If children born in 2007 have a life expectancy of 103, as recent research from the Max Planck Institute predicts, then the stages of life will inevitably be stretched out.

"Will the 'Seven Ages of Man' become eight, 10 or 12 as we extend our lifespans?" Prof Harper asks.

Only time will tell.

- Published10 January 2012

- Published8 December 2011

- Published19 October 2011

- Published11 July 2011