Concerns rise over rugby concussion risk

- Published

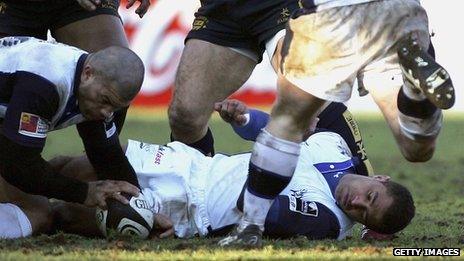

Concussion is the fourth most common injury in the English rugby Premiership

Irish international rugby player John Fogarty was shocked when doctors advised him to retire from the sport.

He had never gone under the surgeon's knife during his entire 11-year professional career and had made his international debut for Ireland only a year before.

But he had been suffering repeated concussions.

For a while he had been able to manage the splitting headaches, memory loss, light sensitivity and trouble sleeping.

But he was tired and irritable, and got annoyed for no reason with his wife and young daughter.

John Fogarty was 33 when he was forced to retire

It wasn't just the times he had been knocked out that had affected him. It was also the smaller "bangs" to the head that he didn't even realise were concussions.

He started to worry when, a few months after retiring in 2010, he was still getting headaches, having emotional difficulties and experiencing memory loss - a result, he believes, of two concussions in his final match for Leinster against Treviso.

"I started really worrying about my brain. After maybe three or four months it settled but the symptoms didn't all go away."

Punch drunk syndrome

Now research from the US into the long-term effect of repeated concussions on athletes playing collision sports is shedding new light on a sports injury about which relatively little is known.

Rugby's governing bodies are keen to stress the differences between their sport and those played in America.

However the news that repeated head impact has led to a form of dementia in a small group of American football and ice hockey players prompted former Scottish international, John Beattie, to become the first rugby player to promise to donate his brain to neuroscience.

The research by scientists at Boston University revealed that a degenerative brain disease called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) had been found in the brains of 30 former NFL players. Prior to death, their symptoms had been the same found in boxers suffering from CTE's more widely known name, punch drunk syndrome.

It's a form of progressive dementia with symptoms including memory loss, depression, speech problems, mood changes and trouble walking.

Dr Bob Cantu, a professor of neurosurgery at Boston University and one of the drivers of the research, said he is certain athletes from sports outside American football have also developed CTE.

"We've studied brains of deceased NFL players and National Hockey League players," he said.

"In the brains of both, we've found CTE and I would be amazed if we did not find the same in rugby players, or at least some rugby players who played rugby for a long period of time and had taken quite a bit of head trauma over the course of their careers."

Concussion management

However, since no work has yet been done to examine rugby players' brains after death, there is no hard evidence for his claim.

British neuropathologist Dr Willie Stewart is one expert who urges caution.

He said the brains of every American footballer who died would need to be studied to get an idea of the prevalence of CTE, and cited studies that show that only between 10-20% of boxers who have taken heavy head punishment develop symptoms.

"It would seem quite remarkable if repeatedly injuring the brain in some way at a low level didn't leave you with some sort of damage," he said.

"But if we followed the research from the US word for word, we would expect whole swathes of rugby players to be clogging up nursing homes, but they aren't."

Bodies including the International Rugby Board, Rugby Football Union (RFU) and the Scottish Rugby Union (SRU) are taking the issue seriously and say they have already adopted new measures and are trying to educate medical staff and players at all levels of the game about concussion management.

Player honesty

According to the RFU, concussion is the fourth most common injury in the English professional game, with five instances per 1,000 hours of play. Among amateurs it's slightly less. But those figures assume that players are aware of all concussion symptoms and are reporting them.

The RFU's head of sport medicine, Dr Simon Kemp, said measures to identify and treat concussions are improving every year.

"The thesis is, if you manage the acute concussion well, your risks of a bad outcome in the long term are a lot less.

"Players are warriors, they don't want to leave the field and assessing someone's cognition, balance and symptoms in the middle of a game is difficult. You rely on the player being honest in reporting his symptoms."

Another former Leinster and Ireland player, Bernard Jackman, admits he often failed to report symptoms of concussion when he was playing.

He suffered more than 20 concussions in his final three seasons before retiring and sometimes had to watch the match back on video the day after because he couldn't remember the score.

"The more concussions I had the more chance there will be of suffering from a brain-related disease or disorder later on in my life, but what can I do now? It's done. I'm not suffering any symptoms at the moment. I put it at the back of my mind."

- Published19 March 2012