Nerve rewiring helps paralysed man move hand

- Published

A paralysed man in the US has regained limited use of his hand after pioneering surgery to bypass damage to his spinal cord

A paralysed man has regained limited use of his hand after pioneering surgery to bypass damage to his spinal cord.

His injury meant his brain could not "talk" to his hand, meaning all control was lost.

Surgeons at the Washington University School of Medicine re-wired his nerves to build a new route between hand and brain.

He can now feed himself and can just about write.

The 71-year-old man was involved in a car accident in June 2008. His spinal cord was damaged at the base of the neck and he was unable to walk.

While he could still move his arms, he had lost the ability to pinch or grip with either of his hands.

Rewiring

The nerves in the hand were not damaged, they had just lost the signal from the brain which told them what to do.

However, the brain could still give instructions to the upper arm.

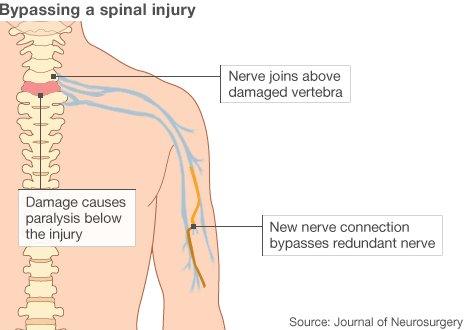

The operation, <link> <caption>described in the Journal of Neurosurgery</caption> <url href="http://thejns.org/doi/full/10.3171/2012.3.JNS12328" platform="highweb"/> </link> , rewired the nerves in the arm to build a new route from brain to hand. One of the nerves leading to a muscle was taken and attached to the anterior interosseous nerve, which goes to the hand.

Ida Fox, an assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Washington University, told the BBC: "The circuit [in the hand] is intact, but no longer connected to the brain.

"What we do is take that circuit and restore the connection to the brain."

She said it was a "really novel" and "refreshingly resourceful" way of restoring movement. However, she warned this would never restore normal function. "That isn't going to happen," she said.

Training

The surgery is not an overnight miracle. It takes intensive training to regain control of the hand. Nerves that used to bend the elbow are now making pinching movements.

After eight months, he was able to move his thumb, index and middle fingers. He can now feed himself and has "rudimentary writing".

With more physiotherapy, doctors expect his movement will continue to improve.

Dr Mark Bacon, the director of research at the charity Spinal Research, told the BBC: "One of the issues with techniques such as this is the permanence of the outcome - once done it is hard to reverse.

"There is an inevitable sacrifice of some healthy function above the injury in order to provide more useful function below.

"This may be entirely acceptable when we are ultimately talking about providing function that leads to a greater quality of life.

"For the limited number of patients that may benefit from this technique this may be seen as a small price to pay."

The technique would work only for patients that have very specific injuries to the spinal cord at the bottom of the neck. If the injury was any higher then there would be no nerve function in the arms to harness. If it was any lower then patients should still be able to move their hands.

- Published20 May 2011

- Published13 July 2011