Why food 'traffic-light' labels did not happen

- Published

Research shows that health food makes people believe they can eat more.

Britain came close to adopting a traffic-light system of compulsory food labelling to grade the health impact of food products - but, as Jacques Peretti reports, opposition from within the food industry prevented it happening.

In the crucial 15 seconds a consumer takes to decide on a supermarket purchase, the labelling is often the deciding factor.

It means being able to know - at a glance - what goes in to what we eat. But for the food industry, it means being told what they must put on their packaging.

A significant part of the food industry is against legislated labelling. They want the freedom to decide how best to disclose the levels of fat, salt and sugar in their food so that it doesn't damage sales.

Labelling can easily lead to unintended consequences for the consumer according to Pierre Chandon, a visiting Scholar at Harvard Business School, whose research focuses on the ways in which fattening foods can be marketed as healthy.

Prof Chandon's study found people ate more chocolate when they were told it was low in fat

Prof Chandon tested his theory by re-labelling familiar chocolate treats as "low fat".

"We found that just because [the treats] were called low fat, people consumed up to 50% more of them," he said.

"This is something I call 'the health halo'. It's the idea that when the food is marketed as being healthy, people think it has less calories."

Huge implications

In 2006, with obesity levels rising in Britain, several ideas for labelling were examined by the Food Standards Agency (FSA).

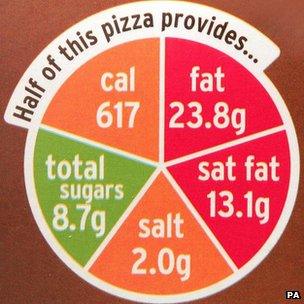

One was guideline daily amounts (GDAs) and the other was a traffic-light system - a postage-stamp sized sticker that used a colour code to denote the percentage of a person's recommended daily allowance contained in each product - red for high, amber for medium and green for low.

The results of consumer tests were clear, according to Richard Ayre, who sat on the board of the FSA at the time. "They preferred traffic lights." So did the health lobbying organisations, who saw the scheme as a major step in the fight against heart disease and obesity.

After weighting up the options, the FSA made clear recommendations that traffic lights should be adopted.

But many of the big players in the food industry were opposed to being told what to put on their packaging - especially something as simple as a colour chart, with a damning red sticker.

Companies like Sainsbury's, Co-op and Waitrose took it on - but others like Tesco, Morrisons and Kellogg's stuck with GDAs.

"Were we disappointed that some of the most important supermarkets like Tesco wouldn't even try traffic lights for real? Yes, of course we were disappointed," said Richard Ayre.

"In the absence of a single, clear, simple labelling system, consumers really are at the mercy of the marketing department," he added.

"We know [people] can be convinced by being told that a product is one of their five portions of fruit and vegetables a day, but they're also having their entire daily allowance of sugar, or of salt, or sometimes of saturated fat."

Tesco maintains its GDA labels are clear and simple, and that it is open to discussion about the best way to help customers make an informed choice.

In the end, the FSA's recommendations did not receive government backing, and within six months of the coalition coming to power, it was stripped of its responsibilities for nutrition labelling in England.

Yet traffic-light labels do live on in voluntary guise, with some individual food manufacturers and supermarkets choosing to implement them.

Sainsbury's voluntarily introduced their own version of traffic light labels

"It was back in 2004 and I think it is fair to say that Sainsbury's had lost a little bit of its sparkle," said Judith Batchelar, director of Sainsbury's brand, about the decision to implement the traffic-light system.

"We were really up for driving change within the organisation. What we found with traffic lights was exactly that."

Sainsbury's found customers were surprised by some products, for instance certain flavoured options of yogurts that actually contained high levels of sugar.

"Not that that stopped people buying things," Ms Batchelar said, "they just swapped".

Traffic-light labelling also tended to make foods healthier, she added, as companies tried to avoid having too many red traffic lights.

"Part of the process is saying, 'What kind of traffic light do I want to put on the front of this product, and how hard am I going to have to work to make sure I turn a red to amber, or turn an amber to green?'"

But the majority of food companies in Britain still prefer the GDA system. And in the absence of regulation, there is little motivation to change.

Jacques Peretti presents the final episode of <link> <caption>The Men Who Made Us Fat</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01k0fs0" platform="highweb"/> </link> on BBC Two at 21:00 BST on Thursday 12 July. Watch online or catch up on earlier episodes at the above link. You can also read Jacques Peretti's latest entry on the <link> <caption>BBC TV blog</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/tv/2012/06/the-men-who-made-us-fat.shtml" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Our perceptions of food do not always match reality. An Innocent Pomegranate, Blueberry and Acai Smoothie has 171 calories, a can of Coca-Cola 139 calories.

A Big Mac burger from McDonald's actually has fewer calories (490) than a No Bread Italian Prosciutto & Lentil salad from Pret A Manger (554).

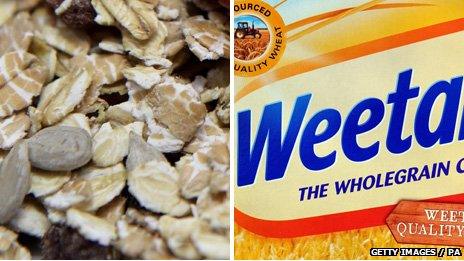

Dorset's healthy-looking Honey Granola Cereal has 2.8g of saturated fat per 100g, but plain Weetabix has a much lower level at 0.6g per 100g.

A Krispy Kreme original glazed doughnut comes in at 200 calories, fewer than a Granola Yoghurt Pot from Eat, which has 306.

- Published13 June 2012

- Published21 June 2012