'Lack of evidence' that popular sports products work

- Published

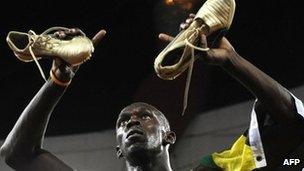

Puma shoes carried Jamaica's Usain Bolt to Olympic Gold in the 100-metre sprint in Beijing in 2008

Consumers could be wasting their money on sports drinks, protein shakes and high-end trainers, according to a new joint investigation by BBC Panorama and the British Medical Journal.

The investigation into the performance-enhancing claims of some popular sports products found "a striking lack of evidence" to back them up.

A team at Oxford University examined 431 claims in 104 sport product adverts and found a "worrying" lack of high-quality research, calling for better studies to help inform consumers.

Dr Carl Heneghan of the Oxford University Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine led the independent research into the claims made by the makers of sports drinks, protein shakes and trainers.

In the case of Lucozade Sport, the UK's best-selling sports drink, their advert says it is "an isotonic performance fuel to take you faster, stronger, for longer".

'Minuscule effect'

Dr Heneghan and his team asked manufacturer GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) for details of the science behind their claims and were given what he said scientists call a "data dump" - 40 years' worth of Lucozade sports research which included 176 studies.

Dr Heneghan said the mountain of data included 101 trials that the Oxford team were able to examine before concluding: "In this case, the quality of the evidence is poor, the size of the effect is often minuscule and it certainly doesn't apply to the population at large who are buying these products.

"Basically, when you look at the evidence in the general population, it does not say that exercise is improved [or that] performance is improved by carbohydrate drinks."

In response, GlaxoSmithKline said they disagreed with the Oxford team's conclusions:

"Over 40 years of research experience and 85 peer-reviewed studies have supported the development of Lucozade Sport and all our claims are based on scientific evidence that have been reviewed and substantiated by the European Food Safety Authority."

GSK is also the manufacturer of the Maxinutrition range of sports supplements, which is endorsed by some of Britain's top athletes, including the Olympic triathalon team and the Rugby Football Union.

Some of GSK's supplements in the Maxinutrition range contain branch chain amino acids which are found in muscle protein. The company says these amino acids "help hard-training athletes recover faster after intense exercise". The supplements sell for as much as £34 a tub.

'Expensive milk'

But the Oxford research team and the British Medical Journal said the science does not back up that claim.

Dr Heneghan said: "The evidence does not stack up and the quality of the evidence does not allow us to say these do improve in performance or recovery and should be used as a product widely."

Nutrition expert Professor Mike Lean of the University of Glasgow described what little evidence there is that certain amino acids, which form part of proteins, may improve muscle strength as "absolutely fringe evidence and I think that that is almost totally irrelevant, even at the top level of athletics".

Prof Lean said the market for supplements is "yet another fashion accessory for exercise… and a rather expensive way of getting a bit of milk."

GSK said in response: "We stand by the evidence that branch chain amino acids can enhance performance or recovery."

But the company said it accepted recently revised rules from the European Food Safety Authority about what claims manufacturers can make about their sports products and supplements and said it will "revise our label accordingly while we gather further evidence required to substantiate the claims we believe can be made".

In the case of trainers, the Oxford team examined the claims made by Puma that their shoes - endorsed by Olympic champion Usain Bolt - are "designed to... minimise injury, optimise comfort and maximise speed".

Dr Heneghan said his team could find no evidence to back up the company's claims and Puma declined to provide his research team with any studies to prove that their shoes can deliver on those claims.

Dr Carl Henegan, University of Oxford, says there is little evidence some expensive sports products work

"That should be really underpinned by good quality evidence... I cannot quite understand how you get from the evidence to that claim. If you can't find research for it, how can you then make that claim?"

Puma declined to reply to the BBC about the Oxford team's findings.

Professor Benno Nigg of the University of Calgary in Canada, has been studying the biomechanics of running for more than 40 years.

He said the conventional thinking was that cushioning and control were the key health benefits of running shoes - but that idea has been proven wrong by recent studies that showed no difference in injury rates if runners were prescribed structured shoes meant to control how their foot lands as they run.

"The most important predictors for injuries are distance, recovery time, intensity and those type of things... the shoes come very, very later as minor contributors."

Prof Nigg's advice to runners is to find something that fits.

"If you can find a shoe where you just enjoy that activity and you are comfortable, that's all you need."

<bold>Panorama: The Truth About Sports Products, BBC One, Thursday, 19 July at 20:00 BST and then available in the UK on the </bold> <link> <caption>BBC iPlayer</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01l1yxk" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

- Published12 March 2012

- Published17 April 2012